On May 15, 1874, 23-year-old Charles W. Walker, the proprietor of a mill at 602 Broadway that manufactured bottled champagne cider, was arrested and charged with cruelty to animals. According to officers from the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), Mr. Walker was overworking his dogs at the mill to the point of suffering, fatigue, and injury.

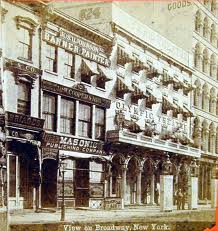

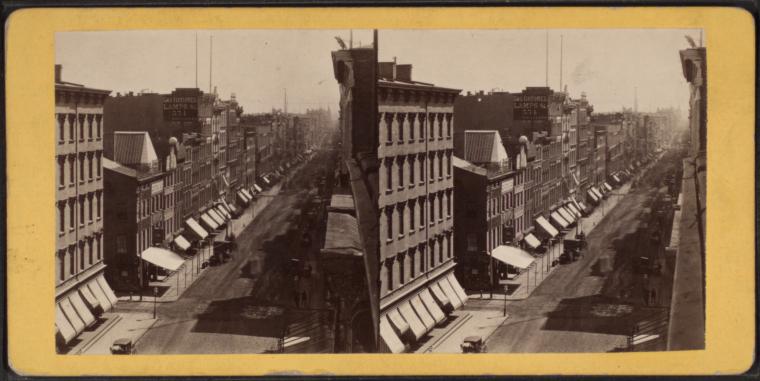

For this curiously odd dog story of old New York, I’m going to take you on a short visual tour of downtown Broadway in the vicinity of West Houston Street, circa 1874, following a brief history of this area.

From the late 1840s through the 1870s, what we call NoHo and SoHo today was at the very center of the “Theatrical Rialto.” It was one of the most thrilling and glamorous parts of Manhattan, offering New Yorkers, businessmen, and tourists some of the finest shops, hotels, restaurants, theaters, and, of course, all the vices associated with these establishments. This Broadway era of glitzy white marble was a far cry from the residential Broadway of the 1820s and 30s, when glorious churches and rows of stylish red-brick Federal and Greek-Revival private homes lined the street.

For patrons of the theater – primarily men — there were numerous concert halls that offered vaudeville and the blackface minstrel shows that were all the rage in those days.

For the ladies of leisure, Broadway was a shopping Mecca during the daylight hours.

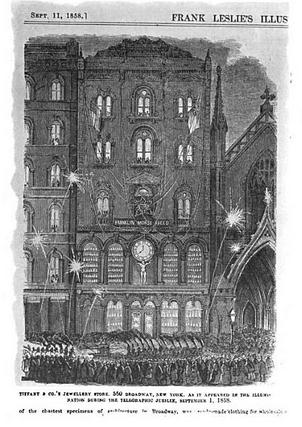

There was Tiffany and Company just north of Prince Street at 550–52 Broadway, Lord & Taylor’s five-story department store on the northwest corner of Broadway and Canal Street, and Brooks Brothers at 668–674 Broadway near Bond Street.

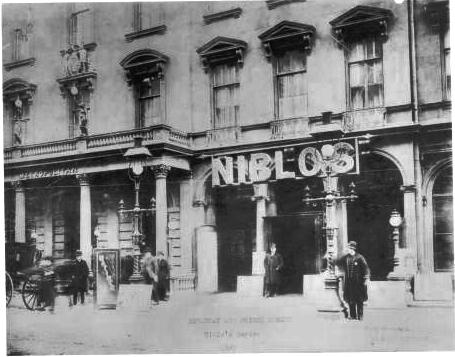

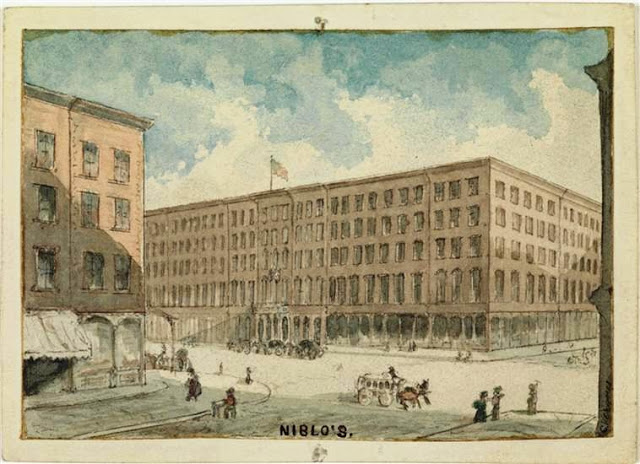

Most of the halls changed management and marquee names every few years or so, and it seems like a majority were damaged or destroyed by fire at least once during their short life spans, but a few of the more memorable ones were still operating in the 1870s. These included Tony Pastor’s Opera House at 585 Broadway, the new Olympic Theatre at 622-24, Theatre Comique at 514, and Niblo’s Garden behind the Metropolitan Hotel at 578-60 Broadway.

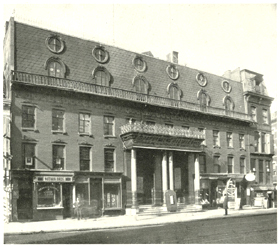

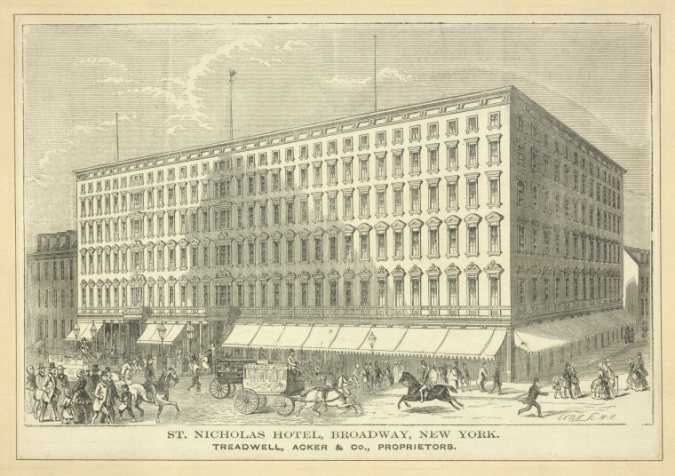

Woven throughout the theaters and shops were some of the city’s most grandiose hotels, including the Grand Central Hotel at 673 Broadway and the famous white marble St. Nicholas Hotel, which stretched 100 feet between Spring and Broome Streets.

There were also numerous smaller hotels on the European plan that charged $1 or $2 a night and were popular with performers and single men seeking temporary housing. These included the Tremont House located next to the Grand Central at 663-665 Broadway, the St. Charles Hotel (formerly Sewell House) at #648, and the Revere House at 604–608 Broadway, which was very popular with the theater and circus performers.

It is just south of Houston Street and one door past the Revere House where the dog tale begins…

The Doggy in the Window

According to news reports, Charles Walker employed several dogs, including a Siberian bloodhound and a Newfoundland, as the motive power in an apple-grinding machine at his factory on Broadway, right next door to the Revere House. The doggie treadmill was placed in the front window each day to attract the attention of passersby.

On the evening of May 15, 1873, Mr. James W. Goodridge of 129 West 17th Street entered the factory and noticed that the Siberian bloodhound working the treadmill was suffering from fatigue and seemed to be starving. The dog also was chafed and bleeding at the neck. Goodridge reported this to the SPCA, who arrested Walker and ordered him to cease and desist until his court hearing.

Due to “severe illness, Walker’s court hearing was delayed for over a year. Apparently he didn’t want to obey orders for such an extended period, so he reportedly began using the dogs on the treadmill again.

This time, ASPCA Officer Dr. William C. Ennever ordered Deputy Sheriff Timothy Kelly to arrest employee Jospeh Bailey for forcing the dog to run the grinding machine. Bailey was arrested on November 21, 1873, locked up and released by 33-year-old Police Justice George E. Kasmire the following day.

Less than eight months later, another employee, Washington Williams, whom the Brooklyn Eagle described as “a sable resident of Thompson Street,” was arrested and charged with cruelty to animals on a complaint made by Henry Bergh, founder and president of the ASCPA. This time it was a Newfoundland that was being used as motive power for the apple grinding machine. Mr. Williams was held on $300 bail by Justice Henry Murray at the Jefferson Market Courthouse.

The Hearing at the Jefferson Market Police Court

Charles Walker finally had his day in court on October 8, 1874. At that hearing, Mr. Bergh appeared before Justices Kasmire, Henry Murray, and Bankson T. Morgan. He reported that the dog’s collar had chafed a raw sore and that he panted and frequently tried to stop, but was so tied that he had to keep on running or choke.

Walker told the judges that he had worked the dogs for years at his factory, never worked them more than an hour at a time, and never chained them up to the machine. However, his father, William Augustus Walker, who owned Walker Glass Importing, Silvering, and Manufacturing Company at 616 Broadway, contradicted his son. He told the judges that the dogs were so fond of working the mill that they had to be chained to prevent them from walking on the treadmill outside of working hours.

Employee Washington Williams also testified at the hearing — and here’s where it gets even more bizarre. Williams told Justice Kasmire that since the dogs had been liberated by the ASPCA, he was being used as the motive power for the machine. Williams said he did not find the work hard at all. Apparently he did not feel it was cruelty to humans either.

After only a few minutes of deliberation, Justice Kasmire announced the decision: The Court found Charles Walker guilty, and sentenced him a fine of $25.

Following this case, Bergh became notorious for frequently storming in saloons where dogs called “turnspit dogs” were being used on cider and fruit presses. He would wave his silver-headed walking stick like a club until the bar managers, who didn’t think it was anyone’s business how they worked their cider mills, backed down and liberated the dogs.

Unfortunately, Bergh often returned to some saloons, only to find that the dogs had been replaced by black children. Mind you, this was just 10 years after the Civil War, and child labor was not against the law — but still, this story shows how far we’ve come in 140 years.