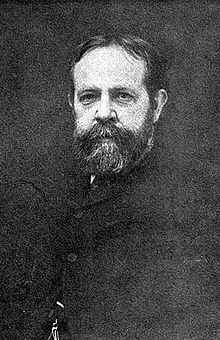

Prior to May 1898, 60-year old Commodore George Dewey was a little-known leader of the U.S. Navy’s Asiatic Fleet. All that changed during the Spanish-American War, when Dewey was wired from Washington to attack the Spanish navy in retaliation for Spain’s assail on the U.S.S. Maine in Havana Harbor. In honor of his success, New York erected the Victory Arch, better known as the Dewey Arch, across from Madison Square Park.

The Commodore directed his command vessel, the U.S.S. Olympia, to Manila Bay in the Philippines, where she was victorious over the rotting wood ships of the Spanish Armada. This stunning naval victory over Spain established the U.S. as a global military power, and elevated Commodore Dewey as the country’s greatest hero.

Once city leaders realized Dewey was coming to New York in September, plans were made for a magnificent two-day tribute that would include a grandiose parade on September 30, a fireworks display, and illumination of the harbor. It was also decided to erect a ceremonial arch and colonnade on Fifth Avenue at 24th Street to permanently honor the war hero. The city hired architect Charles R. Lamb, who, along with fellow members of the National Sculpture Society, designed the $26,000, 100-foot-tall Dewey Arch.

Because there was very little time, however, the planners decided to first build a temporary arch out of staff, which was made of plaster and wood shavings. Later, the arch would be reproduced in white marble and made permanent. (This was how the Washington Square Arch had been constructed just a few years earlier.)

A Home for Olympia and Her Kittens

So what does all this historic stuff have to do with a cat and her kittens? The temporary construction of the Dewey Arch is the key to this Christmas cat tale.

Following the celebrations in September 1899, the arch began to quickly deteriorate. Passing vehicles and carriage wheels made several large holes in the base of the double trophy-columns, and souvenir seekers had also begun chipping off pieces of the arch (bits sold for 15 cents each). But that was just fine for one large grey cat that roamed the streets near Madison Square — a hole in the corner of one of the columns would be the perfect place to give birth to her kittens.

According to the national story first told in The New York Herald, two weeks before Christmas the stray feline took refuge in the hole. The following morning, the cabmen who were stationed across from the Fifth Avenue Hotel heard mewing sounds coming from within. When they investigated, they found the mother cat – whom they named Olympia – nursing four newborn kittens.

The kittens were adopted by the cabmen, who named them Dewey, George, Manila, and Cavite. (Other news articles said Olympia gave birth to seven kittens, who were taken in by Brigadier General Charles E. Furlong, a long-time resident at the Fifth Avenue Hotel. He reportedly cared for them and named them Dewey, Schley, Sampson, Hobson, Sigsbee, Gridley, and Bill Anthony.)

Following the cabmen’s discovery, a nearby shopkeeper provided a bed of excelsior shavings for the feline family’s home and the hotel supplied some food (including raw beef and maybe even some Lobster a la Newberg). The cabmen also donated tidbits from their lunches to help nourish the mother cat.

During the two weeks leading to Christmas, the cabmen and stalwart policemen guarded over the new cat family, protecting them from the newsboys and thousands of other curious strangers who tried to either grab or taunt them. The men also kept a constant lookout for Christmas shoppers who attempted to kidnap the kittens. Olympia often left the niche to stroll down Fifth Avenue on her own, although on one of her ventures she carried a kitten in her mouth and presented it to one of the cabmen.

On Christmas Day, the cabmen and policemen presented Olympia with a special holiday dinner. The New York Times called her “the happiest cat in New York this Christmas,” noting her meal would comprise several courses of “the most luxurious viands to be secured on Fifth Avenue.” The kittens also received a present (although I’m not sure they were too thrilled by this): The cabmen said that once they were old enough, they would all go for a ride in an automobile.

10 Madison Square West)

One of the strangers who took a keen interest in the kittens was a street vendor called Hustling Pete, who made a living selling phony pieces of the arch he made from plaster. Pete came up with a scam to sell phony kittens. He ordered his six children to scour the city streets as far up to Harlem for stray kittens. The children reportedly found hundreds of kittens for their father, who put them in baskets and presented them to the crowds as the original kittens born in the Dewey Arch.

Pete sold about 500 kittens for $1 or more (kittens named Dewy were sold for $2). If true, Pete made a fortune—and 500 stray kittens were lucky to find homes with families who could afford to pay such a high price for a street cat.

The Demise of the Dewey Arch

There are no reports on how long Olympia and her kittens called the Arch their home, but the structure was also apparently home to homeless men in the warmer months. On July 15, 1900, the Times reported many gaping holes in the columns were occupied by transient men (the police called it the Dewey Arch Hotel). In August 1900, The New York Evening Post called the deteriorating arch an “eyesore and disgrace” that was “becoming a public danger.”

An attempt to raise money to have the arch rebuilt with more durable materials failed, and Colonel William Conant Church announced that all donations would be returned. At a meeting of the Municipal Assembly in November 1900, a resolution was passed unanimously by both houses authorizing Commissioner James P. Keating of the Department of Streets and Highways to spend the money appropriated for repairing the structure to tear it down.

On November 15, Mayor Robert A. Van Wyck signed an ordinance directing the demolition of the arch; at 8 p.m. that same day, the crew — a dozen men with pickaxes, crowbars, and shovels — appeared at Madison Square and started to remove the columns.

A few days after the demolition work had begun, the committee received an offer for the arch from Bradford Lee Gilbert, architect for the South Carolina Inter-State and West Indian Exposition. Although a crowd of boys had punched holes in the top (making it look like “a colossal pepper box”), Gilbert took what was the left of the arch back to Charleston.

In June 1902, the exposition closed and the Art Palace, along with the remains of the arch, was demolished. (Although who knows, there may also be some pieces of the arch among old keepsake boxes in closets or attics.)

Another piece of New York City history. Wonder if Admiral Dewey was father of (or related to) Thomas Dewey – the man who almost became President.

Yes, Thomas E. Dewey, 47th Governor of New York and two-time Republican candidate for President, was the son of George Dewey. But his father was a newspaper editor in Michigan.

Admiral George Dewey did have a son, but his name was also George. The Admiral did consider running for president himself, in 1900 (on the Democratic ticket), but he withdrew from the race and endorsed McKinley.

[…] traveling to New York in March 1900 so Princess Lwoff could paint Admiral George Dewey, the newlywed couple moved to a villa in Bavaria. The princess, however, soon grew tired of the […]