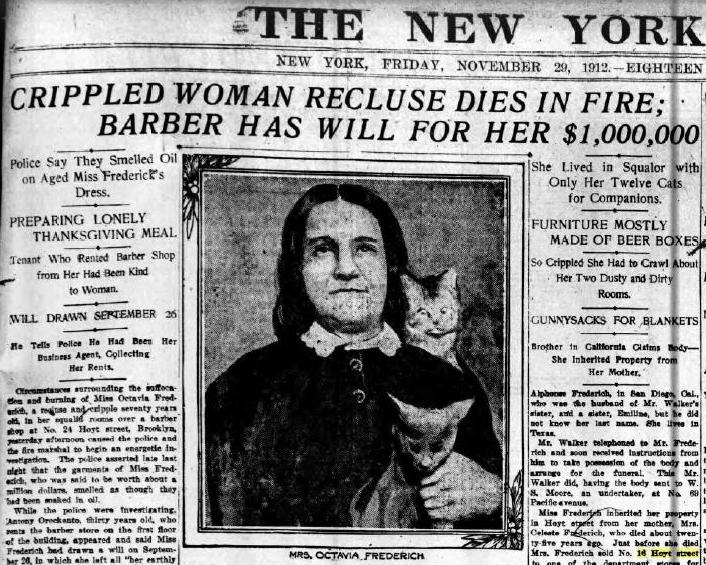

In one of a cluster of six shabby little frame houses at Hoyt and Livingston Streets, Brooklyn, stubbornly holding their own there against the huge overshadowing business buildings reared all about them, there lived until yesterday a hermit spinster, Miss Octavia Fredericks. The neighborhood was full of stories of her, many of them purely legendary and most of them second-hand, for the neighbors did not see her. A cripple, she clung to the two rooms around the barber shop at 26 Hoyt Street, never leaving the rooms once in 3 years, and never allowing anyone to enter them except the twelve cats…and the barber.— The New York Times, November 29, 1912

The Cat Lady’s Tiny Apartment at 24 Hoyt Street

“Miss Frederich always insisted upon having twelve cats,” the barber said. “She had twelve cats always with her in the two little rooms. She was superstitious about twelve cats. She did not care what kinds of cats there were as long as there were twelve of them, and many times a day she would round them up and take roll call to see that she had the twelve. If one cat died, I’d have to get her another one.”— New York Herald, November 29, 1912

On December 5, 1912, one week after Thanksgiving, hundreds of Christmas shoppers in the Fulton Street department store district of downtown Brooklyn observed what The New York Times called “a lively cat hunt.” About eight cats that had been living with a single elderly woman at 24 Hoyt Street were making a nuisance in the neighborhood, and so the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) was called in to round them up.

All of these cats had survived a fire in their mistress’ tiny apartment, which took the life of Octavia Frederich (aka Friedrick, Fredericks, and Friedrich) and four other cats on Thanksgiving Day.

Although detailed reports of the fatal fire in The New York Times, New York Herald, New York Tribune, and Brooklyn Eagle vary quite a bit – for example, the Times said that Octavia was 70, crippled from birth, and lived in a two-room apartment at 26 Hoyt Street; the Eagle said she was 60, was crippled by a stroke about 10 years earlier, and had four rooms at 24 Hoyt Street – I’m leaning much more toward trusting the Brooklyn paper on this one (although she about 72, not 60).

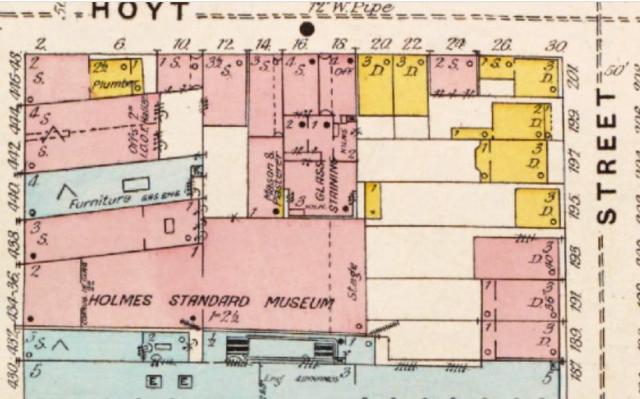

After all, while the Times reported that Octavia owned six frame houses between Fulton and Livingston streets, the Eagle was more accurate in stating that her property consisted of four dwellings: two small, two-story brick buildings, a one-story frame store, and a three-story frame house at the northwest corner of Hoyt and Livingston streets. One just needs to look at the Brooklyn map above from 1887, this 1904 Brooklyn map, and this 1916 Brooklyn map to see that the Times did not get the story quite right.

The Poor, Land-Rich Woman

Born in Metz, Alsace-Lorraine, Octavia Friedrich was the daughter of Celestine Celestine Friedrich and Charles W. Frederich, a tailor. Sometime around 1862, the family, including 22-year-old Octavia and her siblings, Amelie, 20, Alphonse, 28, Lucy, 21, and Ernest, 18, left France to move to America. They settled in Brooklyn on property once occupied by Brooklyn Mayor Samuel Smith’s farm, and Charles and Celestine began investing in real estate. According to the census, all five siblings were still single and living with their parents in the three-story frame house at 201 Livingston Street in Brooklyn in 1865.

With both her sisters married and gone (Lucy married a prominent Brooklyn music teacher but died before 1875, and Amelie moved to the Seattle area with Brooklyn attorney Newton H. Crittenden), Octavia continued living at 201 Livingston Street with her mother until Catherine died in February 1893.

According to the terms her mother’s will, Octavia had a life interest in the four buildings comprising #24-30 Hoyt Street, even though the real estate holdings had been divided among the three living siblings. A quarrel reportedly ensued over this division, causing a rift between Octavia and her surviving brother and sister.

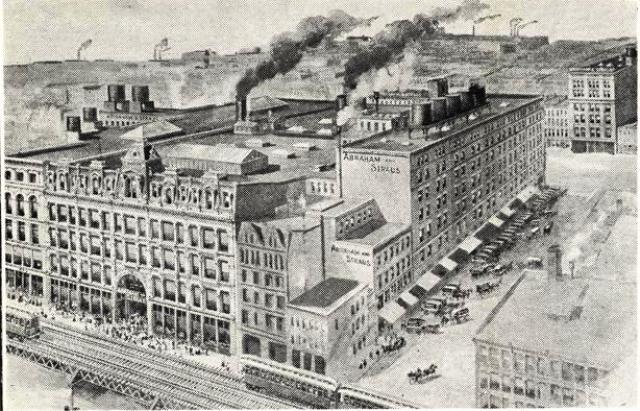

Fast-forward 10 years to 1905, when the Friedrich estate sold 16-18 Hoyt Street to Abraham & Straus for a reported $100,000. The department store called the 5-story building the Men’s Building, as it was dedicated to men’s apparel.

By 1912, all of the remaining Friedrich holdings on Hoyt Street were in bad repair, and, due to a high assessed value, barely paid enough rent to pay the high taxes.

According to the Brooklyn Eagle, Octavia’s apartment comprised a small kitchen and three small rooms that were filled with so much rubbish – boxes, old tins cans, milk and wine bottles — they were impassable. The cats lived in the rubbish-filled rooms, while Octavia spent her time in the kitchen, where she had an old coal stove and rusty range, an upholstered chair, a bureau, a small sink, and a tatterred mattress perched atop boxes (a good bed was wrapped up and propped against a wall and did not appear to be used).

The Thanksgiving Fire

On November 28, 1912, Octavia reportedly told a neighbor she would be cooking a small turkey for Thanksgiving. Some reports suggest she fell asleep and hot coals from the stove fell through the cracks and set fire to some gunnysacks; other reports theorize that a cat tipped over a kerosene lantern. Whatever the cause, that night around 6 p.m., Patrolman John Shaughnessy of the Adams Street police station saw flames through the dust-smeared second-floor windows of the building and pulled the fire alarm.

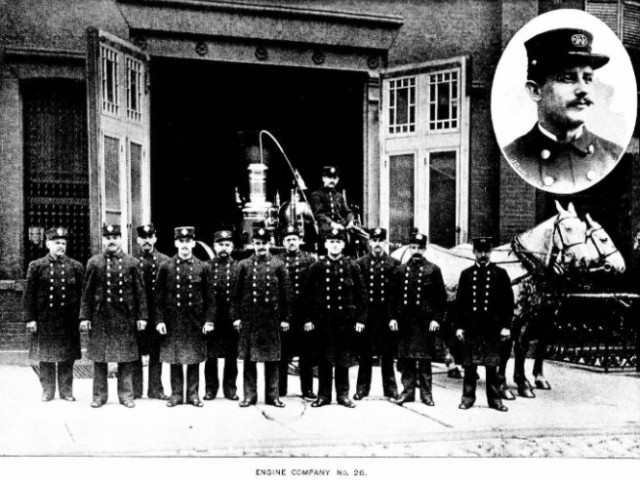

The first fire engine to arrive on the scene was Engine 126 from State Street, just a few blocks away. Brooklyn Fire Department Chief Charles Furey made his way through the unlocked door in the hallway, but the entrance to the three back rooms was blocked, so he had to force the door to the kitchen. By this time the apartment was filled with black smoke, and the fireman could barely see anything as they put out the fire.

The Barber and the Will

When the firemen returned to the streets, they were met by two women who came out of a restaurant yelling, “Did you find the body? Did you find old Mrs. Fredericks?”

The men went back into the kitchen, where they found her in the upholstered chair by the stove. Ambulance Surgeon Buckley from the Brooklyn Hospital said he thought she had suffocated from smoke inhalation, which was confirmed by undertaker W. Fred Moore.

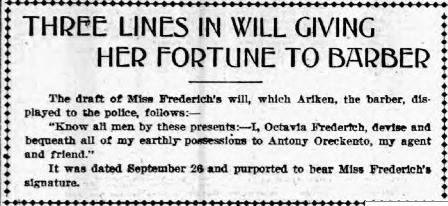

Police got suspicious, however, when Anthony Oreckinto, the barber with a troubled past (his sister shot and killed her husband, and his mother died in a fire at 325 Atlantic Avenue a few years earlier), told them that he was the sole beneficiary of Octavia’s will.

Anthony, who lived nearby at 159 Hoyt Street, told police he had been collecting all the rents and depositing the money in the bank for Olivia Friedrich for the past few years. The last rents he collected totaled $498, which he turned over to her in cash just two days before. Aside from her cats, he said he was the only one ever allowed in her apartment.

“She told me that I had been her good friend for many years; that she had had a bitter quarrel with her relatives, and that she felt that by making the will she was only doing the fair thing by me,” Anthony said.

The barber also said he had signed the will on September 26 in the presence of two witnesses, and that one copy was in a drawer in her room and the original was in a safe deposit box at the the new Dime Savings Bank on Fulton Street.

Three people came forward to dispute this claim, including R.P. Chittenden, Amelie’s nephew by marriage; Russell Walker, Alphonse’s brother-in-law; and Mrs. Laura Morris, who rented a basement from Octavia in which she operated a restaurant.

The nephew said Octavia Friedrich was in no condition to write a will because she was “deranged” – hence all the rubbish and cats in her apartment. Russell said she was far less rich than the neighborhood gossip reported her to be because she only had a life interest in the property and could not sell the Hoyt Street buildings. Mrs. Morris said she always paid her rent directly to Octavia, and that Octavia had recently confided in her that a man had approached her and asked her to sign a piece of paper.

Because Lieutenant James Kennedy had noted earlier that Octavia’s clothes smelled as if they had been soaked in kerosene, an investigation was ordered. Lieutenant William Roddy alongside Fire Marshall Brophy conducted a thorough investigation but concluded that the fire accidental, and that Octavia’s death was caused by suffocation and burns.

In June 1913, Kings County Surrogate Judge Herbert T. Ketcham declared the will invalid. Records showed that the only property she owned outright was 323 Madison Street — now the site of the Hattie Carthan Playground — which was valued at about $8,000 (the deed was dated June 4, 1898).

The Hoyt Street property — 140 feet on Hoyt and 60 on Livingston — was valued at $150,000 to $175,000. The judge turned this property over to Alphonse and Amelie.

Eight years after the fatal fire, 24 Hoyt Street was advertised as the Rose Waist Shop (Rose Shirtwaist Company). Next door, at 22 Hoyt Street, a flower shop was operated by Charles Abrams. By 1928, all the old buildings at the northwest corner of Hoyt and Livingston had been demolished to make way for the large Art Deco addition to A&S designed by Van Vlech and Starrett and constructed from 1929-1930.

Today, Abraham & Straus — now Macy’s — is an amalgamation of 8 buildings between Hoyt, Fulton, Livingston, and Gallatin Place. And the old boarding and livery stable that was once across from Octavia’s apartment is a giant parking garage for the department store.