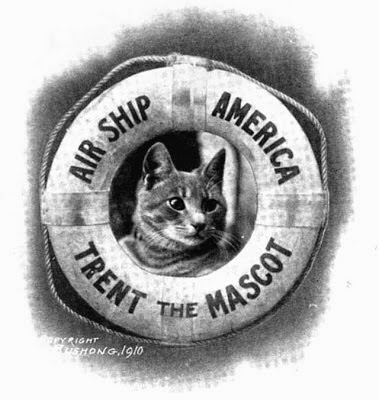

The story of Trent, the large tabby cat made famous by an unsuccessful flight across the Atlantic in the airship America, has been told many times. My version of the story has a New York City history twist that you will not find in any other tale about Trent.

On October 22, 1910, a month after the new Gimbel Brothers Department Store opened at Greeley Square in New York City, Walter Wellman’s 27-foot lifeboat and the large tabby cat that was rescued from his hydrogen dirigible, America, were on exhibition on the fourth floor of the new department store.

Trent, lying atop comfy pillows in a gilded cage, attracted crowds of sightseers — especially women and children — who couldn’t wait to meet the famous cat that attempted a trans-Atlantic crossing in an airship. As a continuous line of people tried to pet and woo him, Trent ignored their attention and declined to be sociable.

I’m going out on a limb here, but maybe the poor cat was trying to ignore everyone because he had just gone through a very dramatic experience that I know for a fact would have traumatized most cats for all the rest of their nine lives.

From Atlantic City Stray to Airship Mascot

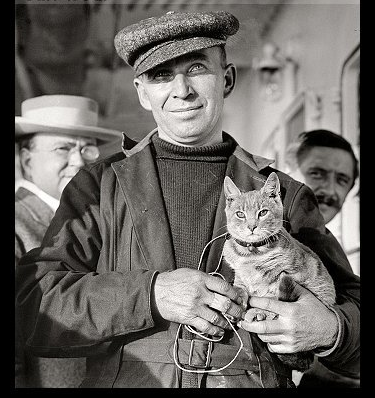

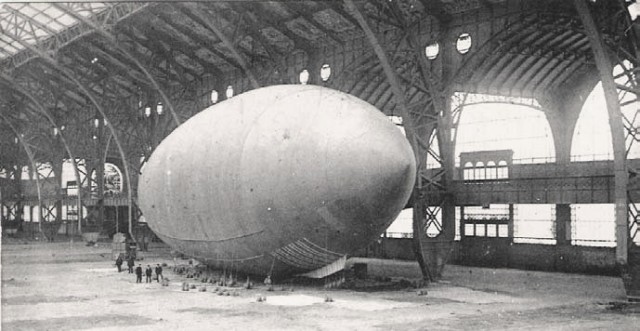

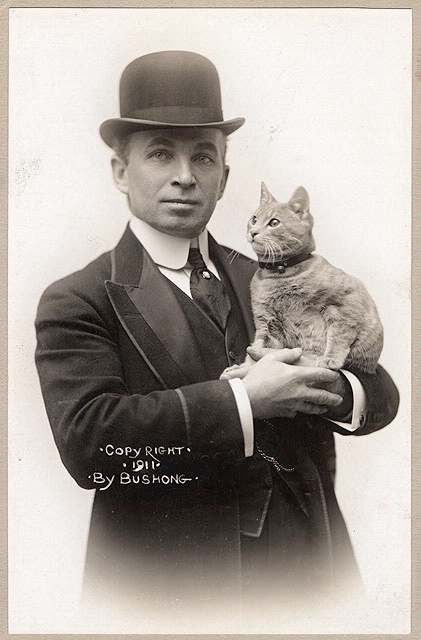

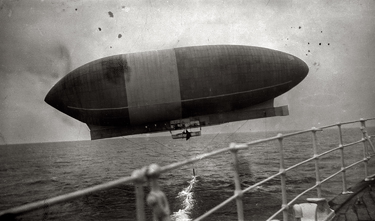

In October 1910, journalist and pioneer airman Walter Wellman and five companions prepared to cross the Atlantic Ocean in the airship America. Trent was just a stray cat living with his twin brother in the airship’s hangar in Atlantic City when the airship’s navigator, Murray Simon, decided it would be good luck to have a cat on board the historic flight.

Trent — then called Kiddo — was tossed into the lifeboat, which was attached just under the airship. Here, radio man Jack Irwin had his post (America was the first aircraft to carry radio equipment).

No surprise, Kiddo was not too fond of his situation, and he put on a great display of anger and terror by meowing and running around the small space in hysterics.

Chief Engineer Melvin Vaniman was reportedly so annoyed by the antics of Kiddo that he made the first-ever in-flight radio transmission to a secretary back on land. “Roy, come and get this goddamn cat!” he yelled.

The plan was then to lower the cat in a canvas bag to a motorboat that was running beneath the airship. Unfortunately, the seas were too rough for the boat to catch the bag, so Kiddo was forced to continue the journey.

Eventually, Kiddo settled down and took his job as feline co-pilot quite seriously. (One of his duties was to try to keep the napping men awake by lounging on their faces.)

Navigator Murray Simon, who had told the press that one must never cross the Atlantic in an airship without a cat, wrote that Kiddo was “more useful than any barometer.”

Although the airship set several new records by staying aloft for almost 72 hours and traveling over 1000 miles, weather and other problems forced the crew to ditch the airship and join Kiddo in the lifeboat. Somewhere west of Bermuda, they sighted the Royal Mail Steamship Trent. After using Morse code to attract the ship’s attention, Jack Irwin made the first aerial distress call by radio.

As the airship drifted out of sight — never to be seen again — the crew of the RMS Trent rescued all the men and their cat Kiddo and returned them to New York. Murray Simon reminded the crew that it had been a good idea to bring Kiddo on the journey, because cats have nine lives.

Trent Goes to Gimbels

Following the airship’s rescue, Melvin Vaniman and Kiddo — now called Trent — were invited to help the Gimbel brothers celebrate the opening of their New York store on Broadway and 32nd Street. As this blog explores the history of New York City through animal stories, a pictorial look at the history of Gimbels is in store.

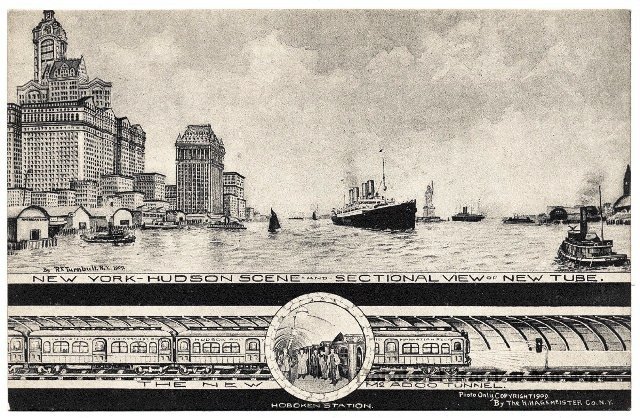

Although Gimbel Brothers New York officially opened on September 29, 1010, the history of this particular store at Greeley Square goes back to 1874, when the Hudson Tunnel Railroad Company initiated plans to construct a railroad that would connect New Jersey and New York City via a tunnel under the mile-wide Hudson River (today we call this the PATH train).

Construction began in 1874, but litigation and lack of funding caused numerous delays over the years. Finally in February 1902, the New York and Jersey Railroad Company took over all of the railroad company’s tunnels and lines of railway, including 4,000 feet of tunnel that had already been constructed.

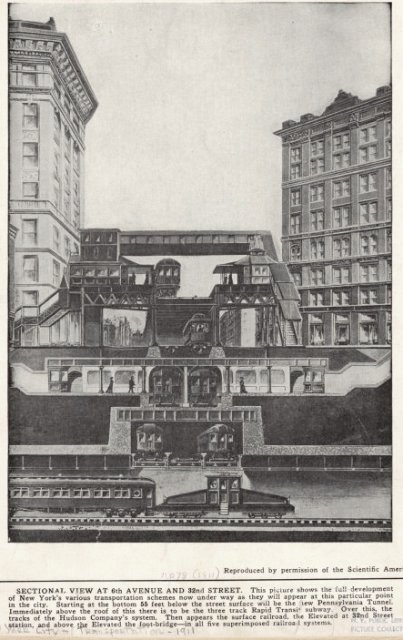

In 1904, the newly formed Hudson and Manhattan Railroad Company (H&M) filed an application to extend the McAdoo Tunnel to a larger underground terminal on Sixth Avenue at 33rd Street. The proposed site was occupied by several landmarks, including Trainor’s hotel and restaurant and the Manhattan Theatre (formerly the Standard Theatre) on Sixth Avenue, all of which were condemned and demolished in 1905.

Many smaller old buildings on West 32nd and West 33rd streets were also condemned, including a house of prostitution called the House of Nations and six other properties owned by Albert J. Adams. Incidentally, Al Adams, as he was called, also had grand plans for the same site: In 1905 he had proposed to build a 42-story hotel on the site that was to be the tallest building in the world — more than 125 taller than The Times building and the Park Row Building, which were then the world’s tallest buildings.

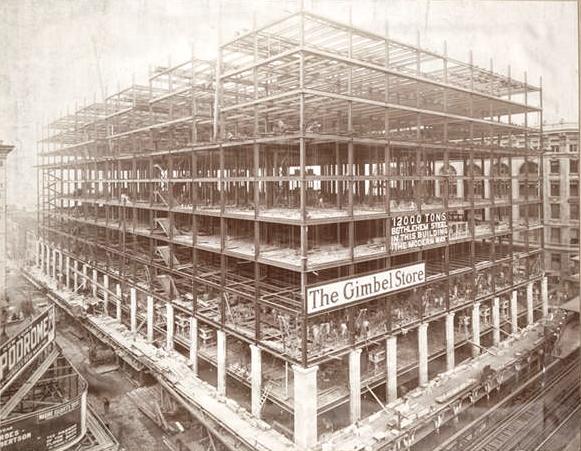

On April 23, 1909, five years after the site was cleared to make way for the McAdoo system concourse at 33rd Street, the Gimbel brothers — Jacob, Isaac, Charles, Daniel, Ellis, and Louis — signed a 21-year lease with the Greeley Square Realty Company for the land atop the proposed terminal (the 33rd Street station did not open until November 1910). Daniel Burnham (of Flatiron Building fame) was hired to design the new building.

On January 30, 1909, The New York Times announced that the “massive store” would “be the terminal of the McAdoo tunnel system, or Manhattan tunnels, which, by the time the store building is completed, will connect with the Pennsylvania Railroad, Central Railroad of New Jersey, the Erie system, and the Lackawanna & Western Railroad, handling, it is estimated, 1,000,000 persons daily.”

On December 8, 1909, a copper box containing a history of the Gimbels and other data was placed in the cornerstone. The $12 million building was completed ahead of schedule on June 11, 1910.

In October 1925, Gimbel Brothers announced the purchase of the Cuyler Building on the south side of 32nd Street. To connect the Gimbels store with the Cuyler Building, a three-story, copper-clad sky bridge was constructed. This bridge still stands today, albeit, it is no longer functional (check out these amazing photos taken inside the sky bridge in 2014.)

On June 6, 1986, the Associated Press reported that Gimbels was going out of business. Today, the building that once paid tribute to a hero cat named Trent houses a JCPenney and the Manhattan Mall.

As for Trent, he lived out the rest of his eight remaining lives on land with Edith Wellman, the daughter of Walter Wellman, in Washington, D.C.

So what happened to Trent after he was at Gimbel’s?

Thank you for asking! In fact, since you did, I’ve added this last bit about Trent to my story: As for Trent, he lived out the rest of his eight remaining lives on land with Edith Wellman, the daughter of Walter Wellman, in Washington, D.C.