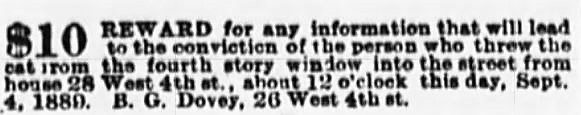

Benjamin G. Dovey offered a $10 reward for information leading to the capture of the person who tossed a cat from a fourth-story window on West Fourth Street.

On September 4, 1889, Benjamin G. Dovey offered a $10 reward for any information leading to the arrest of the person who had tossed a glossy black cat with tiger stripes from a top-floor window of the brick house at 28 West Fourth Street. “If I can discover the guilty wretch who hurled that poor, harmless creature from the top of a four-story building I shall only be too glad to pay the $10 reward offered,” the gray-haired, gray-whiskered man told the press.

Dr. Benjamin G. Dovey, who was well-known among affluent New Yorkers as a very competent veterinary surgeon and taxidermist, was also an agent for the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. A day after his ad for the reward appeared in The World newspaper, he told reporters that aside from the “beastly human nature” displayed in the cruel act, an offense had also been committed against the laws of the state.

Joseph’s face was reportedly “full of sympathy as he tenderly laid the cat down on the counter before the doctor.” (This is not a photo of the cat who was tossed on West Fourth Street but she’s a cutie.)

As he began to tell the story to the press, Benjamin called for Joseph, his assistant, to bring the badly injured cat into the reception room of what was billed as an animal hospital and hotel at 26 West Fourth Street. The cat was extremely thin, and its yellow eyes were immense. The little cat had a look of pain and misery on its face.

According to Benjamin, the cat was probably around two years old. Three of her ribs were broken and both rear thigh joints were dislocated in the fall. He explained the fall to the reporters:

“Yesterday it came crashing down from the top of the building next door. It struck on a sign put up by the agent announcing that the second floor was to let. The pole bearing the sign broke and the cat fell to the pavement below. My young man picked her up and brought her into the hospital.”

The veterinarian said he dressed the ribs and reset the joints, and he expected the cat to survive with proper care and food. He had no kind words for the “brute” who tossed her from such great height, and he vowed to get justice for the feline crime victim.

She Said, She Said, He Said, She Said

According to Benjamin, Mrs. Mattose, who lived on the third floor of 28 West Fourth Street, was certain that Mrs. Dirk threw the cat from her window on the fourth floor. Mrs. Dirk, who was described as a woman of about 35 years with a kind face and several children, denied owning or tossing a cat.

Mrs. Dirk told reporters that she had a lodger who lived in a locked room from which the cat may have been tossed. She said that at the time of the incident, she was in another room at the other end of her apartment. She also said she was looking out the window and saw the incident happen.

“I was here in this window when the poor kitty fell. Could I be here and there, too?” she asked the reporter. There was no further mention or questioning about the boarder who lived behind the locked door.

Mrs. Dirk’s husband, Gustav, said his wife had been wrongly accused “of a bit of dirty cruelty,” and he wanted her name cleared. He said they had been living in the house for seven years and that all their children were born there.

“My good wife would not do such a thing, I know.” He said that although he was a poor man who worked hard for a living at B. Hellrung & Brothers on Bleecker Street, he would also pay $5 to find out who threw the cat from the window.

Mrs. Mattose continued to insist that Mrs. Dirk was guilty, even though she didn’t see her toss the cat. “Mrs. Dirk is always fighting me. She says I am all to blame for it, but I never have any trouble.”

(Eventually, Mrs. Dirk sued Mrs. Mattose for slander and the two women duked it out at the Jefferson Market Police Court. Mrs. Mattose was fined $100 and ordered to keep the peace for three months.)

What is today the Jefferson Market Library on on Greenwich Ave. between Sixth Avenue and West Tenth Street was formerly the Jefferson Market. The block originally housed a dingy police court over a saloon, a volunteer firehouse, a jail, and an octagonal wooden fire lookout tower constructed in 1833. The wood tower and market structures were razed in 1873 to make way for a new civic complex and courthouse, which opened in 1877. In 1927 the jail, the market, and the firehouse were demolished and replaced by the city’s House of Detention for Women. The courthouse was abandoned in 1945 and saved by the Greenwich Village Association in 1962 for use as a public library. In 1973 the House of Detention was torn down to make way for a park. Photo circa 1855-60, Jefferson Market Library.

Benjamin Dovey Increases the Reward

Next, the reporters interviewed Mrs. Biernesdorfer, a tailor on the first floor, who said she very upset that anyone could have been guilty of committing such an outrageous act. She said she could not place the blame on anyone. “I only know that the poor animal came down with force enough to break down the agent’s sign, just at the side of my door.”

George Collet, a dealer in milliners’ goods in the basement, said he was standing in his doorway, which was five steps down from the sidewalk, when he heard the crash and saw the agent’s sign break. He looked up and saw Mrs. Dirk at the window. Then he ran up and saw the nearly dead cat on the sidewalk. He told the reporters that the cat had fallen far from Mrs. Dirk’s window.

About a week later, the cat culprit was still at large. Benjamin upped the ante and raised the reward to $25. Although there was no justice for the cat, the veterinarian said her wounds would eventually heal and she would survive the ordeal physically, if not mentally.

None of the reporters ever inquired more about the lodger on the fourth floor, or about the possibility that the cat was thrown from the roof. Here’s my theory:

Perhaps someone was angry at Benjamin Dovey. Maybe he didn’t like the fact that Benjamin had many barking dogs in his back yard or that a kennel smell always permeated from the door to the animal hospital.

Just five months earlier, someone had tossed a window shutter from the rooftop of the building next door and ran away. The shutter landed near the spot where Benjamin often sat in the afternoon, and just missed hitting a poodle. I’m going to suggest that whoever threw the shutter also threw the cat to send a message to Benjamin.

Benjamin G. Dovey and His Animal Hospital and Hotel

This illustration of Benjamin Dovey caring for a small dog named Eddie appeared in a feature article about the veterinarian in the New York Press newspaper in 1891.

Benjamin Dovey was born in England in 1824. Shortly after marrying his wife Diana in 1855 or so, the couple moved to New York City.

In the early years, Benjamin and Diana operated a shop at 3-5 Greene Street, where they sold dogs and birds and provided care and medicines for domestic pets. They also resided at this address, according to the 1870 census.

Mrs. Dovey’s specialty was caring for the cats, birds, and poodles of the shop’s female customers. Her calling made her quite popular among the aristocratic pet owners in the city.

“By fondling them, their malady seemed to disappear, and it was seldom that restored health did not result from her treatment,” the press reported following her death from pneumonia at the age of 64 in January 1890. She loved the pets under her care, and she was never happier than when in her own home, surrounded by her collection of birds, dogs, and 16 Angora cats, who all lived in peace together.

Sometime during the 1870s, Benjamin and Diana moved to 26 West Fourth Street, where Benjamin offered veterinary, taxidermy, and dog boarding services. In the basement and on the ground floor, Benjamin had large rooms which were filled with shelves that displayed jars of extracted animal tumors and medicine bottles with Latin labels. In the windows, Benjamin showed off his stuffed cats, dogs, birds, snakes, and fish.

The hospital was in the rear of the basement, where animals were treated on beds separated by wire partitions. Over the years, he reportedly treated more than 15,000 animals at the facility.

The dog hotel comprised a large court-like frame enclosure behind the brick building, where Benjamin had sturdy willow cages on all four sides. The hotel dogs also had access to a large back yard. Benjamin charged $7 to $15 a month for each boarder, many of whom stayed with him every summer while their upscale owners vacationed in Europe.

Following his wife’s death in 1890, Benjamin remarried a woman named Ida, retired, and moved to 232 West 50th Street. Unfortunately, the couple didn’t have much time together. Benjamin died on August 8, 1893, following a long illness.

A Brief History of 26 West Fourth Street

The four-story brick house at 26 West Fourth Street, near the southeast corner of Greene Street, was one of numerous properties in the area owned by George G. Kip. Kip was the great-grandson of Annatje Herring and Samuel Kip, whose ancestors (de Kype) had settled in New Amsterdam in the 1630s and later acquired a 150-acre farm called Kip’s Bay Farm on the East River.

This sketch of the Kip Mansion, which was built by Jacobus Kip and located near the Armenian Church on Second Avenue at East 35th Street, was published in 1850, just one year before the 200-year old home was demolished to allow the city to extend 35th Street to the East River.

In the late 1860s, Dottore Sebrino, a professor of vocal music from the Conservatory of Music at Milan, taught Italian singing in his rooms at 26 West Fourth Street. Balletmaster Dumar’s Dancing Academy gave dancing lessons in the ballroom on the second floor during this time. In the 1870s, the building housed a fencing and boxing academy as well as a restaurant, oyster house, sleeping rooms, and dining rooms.

Sometime before 1899, the old buildings at 24 and 26 West Fourth Street were replaced by a single six-story business building with a basement and sub-basement that occupied a 50 x 82 foot plot between Mercer and Greene Streets. In 1899, the building was occupied by Scheyer, Pots & Company, manufacturers of women’s cloaks, capes, and suits.

In 1926, this building and 14 other parcels owned by the heirs of George G. Kip were sold to an investors’ syndicate, which resold the buildings a few weeks later.

The Old Herring Farm

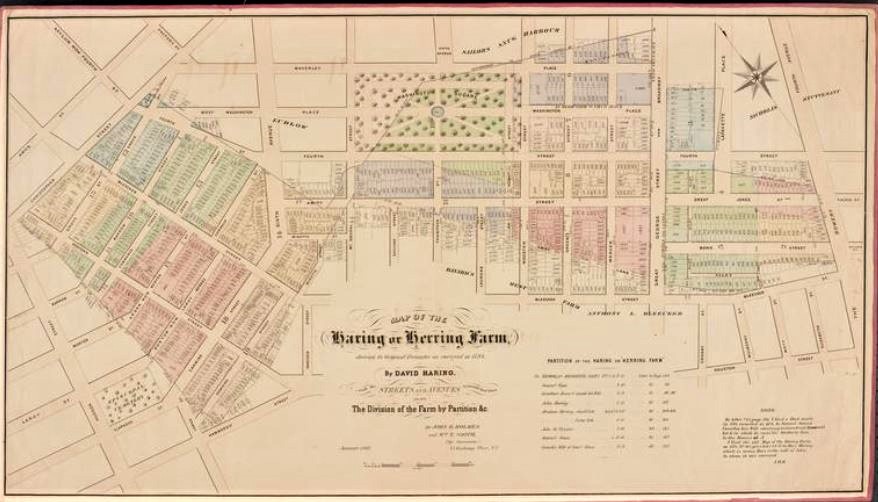

West Fourth Street is located on what was once the farm of Elbert Herring, which was about 100 acres bounded by the Bowery, Washington Square Park North, Bleecker Street, Hudson Street, and Christopher Street. The farm goes back to grants allotted by the Dutch West India Company to Pieter Janszen Haring, who had emigrated to New Amsterdam from the Netherlands shortly after the birth of his son, Jan, in 1633.

Map of the 100-acre Herring (or Haring) Farm. The farm included what would later become Washington Square Park, located near the top center of this 1869 map.

Elbert Herring was born in the area of Niuew Haarlem in March 1706. He married Catherine Lent in 1726, and worked as a baker. The couple had three children. After Catherine died in 1731, Elbert married his first cousin Elizabeth Bogert, who was the daughter of Nicholas Bogert and Margaret Consalyea Tillburg of Bushwick, Brooklyn. They had seven children.

Over the years, Elbert acquired a lot of property, including that of the estate of his maternal grandfather, John Louwe Bogert. When his father, Peter, died in 1750, Elbert inherited the Herring farm.

By the 1770s, Elbert was known as an eccentric old man who did considerable business supplying the city markets with his potatoes, beans, cabbages, and turnips. He died on December 3, 1773, at his home on the Bowery.

According to his last will and testament dated June 17, 1772, Elbert bequeathed all his real estate and financial holdings to his wife and his children: Peter, Nicholas, Abraham, Mrs. George Brinckerhoff (Catharine), Margaret Roosevelt (widow of Cornelius Roosevelt), Mrs. Samuel Jones (Camelia), Mrs. John De Peyster (Elizabeth), Mrs John Haring (Mary), Mrs. Gardiner Jones (Sarah), and Mrs. Samuel Kip (Annatje). The transfer of land, however, was held off until after the Revolution, because the family was forced to abandon any claim to the land and evacuate the city. (The land was located firmly in British territory, and selling it would have amounted to support for the crown.)

Following the war, all of the executors conveyed their portions to Abraham Herring. Abraham then distributed the lots to his siblings as ordered in Elbert’s will. Abraham retained some of his allotted land for his own use, and sold a portion to the city, which used the land–now Washington Square Park–as a burial ground or potter’s field for indigents.

During the Revolution, Annatje (Ann) Herring and her husband, Samuel Kip, lived in Tappan, New York. When they returned to the city, they lived in the old Kip family mansion at Kip’s Bay on the East River, which had been built by Samuel’s great grandfather, Jacobus Kip. They had 8 children from 1765 to 1784. The Kip heirs retained their land on West Fourth Street until George G. Kip’s death in 1925.

New York University Takes Over Washington Square

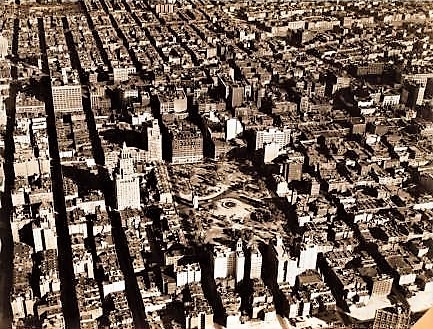

This aerial photograph of Washington Square Park and surrounding streets was taken in 1931, about 25 years before a swath of buildings near the southeast side of the park (top, mid-right in photo) were razed as part of a slum clearance project headed by Robert Moses.

In August 1955, the Mayor’s Slum Clearance Committee, headed by Park Commissioner Robert Moses, proposed a project to clear about 28 acres of unsavory tenements and manufacturing buildings on nine blocks from West Houston Street to West Fourth Street between West Broadway and Mercer Street.

The project, called the Washington Square Southeast Slum Clearance Project, displaced about 132 families (or about 400 people) and 650 small businesses.

By 1960, West Fourth Street had been cleared and was ready for development by New York University.

As part of the deal, New York University was able to purchase the northern three blocks between West Third and West Fourth Streets for a great price; the land was cleared for future development. At the time, the university already owned about 80 percent of the property around Washington Square.

The land sat empty for several years until 1964, when the university leased the land at 40 West Fourth Street to Lincoln Center’s Repertory Theater for a prefabricated temporary theater called the ANTA-Washington Square Theater (the theater, where “Man of La Mancha” played for over two years, was demolished in 1968).

In 1965, NYU opened Warren Weaver Hall, a 14-story column of bronze-tinted brick and glass on the southwest corner of West Fourth and Mercer Streets.

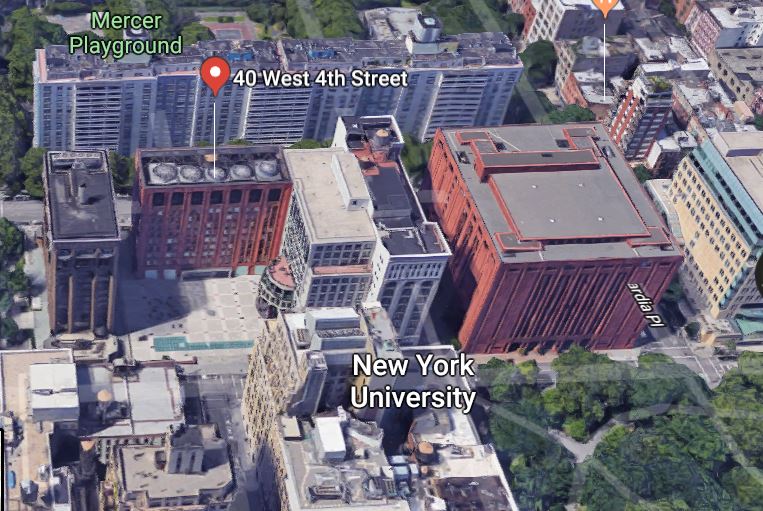

In 1972, the university constructed Tisch Hall at 28-46 West Fourth Street. Now part of NYU’s Stern School of Business, the building and adjoining Gould Plaza have completely erased any memories of a small animal hospital/hotel and a cat that long ago lost several of its nine lives in its fall to Earth.

Where the Tisch Building and Gould Plaza stand today at 40 West Fourth Street, Benjamin Dovey had his animal hospital and hotel from about 1872 to 1890.

I always enjoy reading your posts, but this one especially struck a chord with me. It’s sadly not surprising that animal cruelty has a long history, but the fact that so many people were outraged by this situation, and worried for the cat, is a reminder that human decency and kindness also go back quite a long way. What happened to this poor cat is awful, but she was also awfully lucky to have fallen in such a place where kind people and a notable veterinarian were on hand to help her, even if the culprit was never caught!

It’s also interesting that this happened on what’s now the NYU campus. I went to college there and now, whenever I go back to visit, I will definitely see this area with new eyes!

Thanks for another excellent, well-researched post!

So glad you enjoyed it! I have quite a few really sad, cruel stories on my computer that I haven’t yet published because they are so hard to tell — and yet very important to share. I graduated from Syracuse University and got my masters at Boston University, but in between I took several continuing ed courses at NYU. Whenever I pass by a location that I have written about, I always stop for a minute or so, close my eyes, and try to picture what it was like 100 or 200 years ago. I know for sure that the next time I am near Washington Square and Gould Plaza I will stop and think about Dr. Dovey and this little kitten.