The story of Caroline G. Ewen begins in the summer of 1890, when five women decided to devote their lives to improving the lives of city cats and dogs. They formed the Society to Befriend Domestic Animals, and set out to find the perfect house to rent in a remote part of the city so as to not disturb the neighbors. They found such a place in Washington Heights, on Amsterdam Avenue between 185th and 187th Street.

Their mission was “to provide shelter and food for the homeless and maltreated animals; to secure painless death for animals rendered decrepit by accident or incurable ailment; to secure through educative agencies the repression of all forms of cruelty to animals.”

All was fine and well for homeless cats until 1893, when the women were forced to leave the dilapidated farmhouse. Without a shelter to house the animals, they turned to another method to help “save” the feline population of New York City–mercy killing via chloroform.

Armed with catnip, airtight baskets lined with oilcloth, and sponges saturated in chloroform, up to 20 volunteers would roam the streets late at night to “save the souls” of the homeless cats. They called themselves the Midnight Band of Mercy. Their main benefactor and volunteer was Caroline Ewen, the wealthy daughter of Civil War Brigadier General John Ewen and his wife, Maria.

Although several of the women were eventually arrested, and the Midnight Band of Mercy was disbanded, Caroline continued saving cats in a slightly more humane way–this time via cat hoarding at her home.

Caroline Ewen and Her 80 to 180 Cats

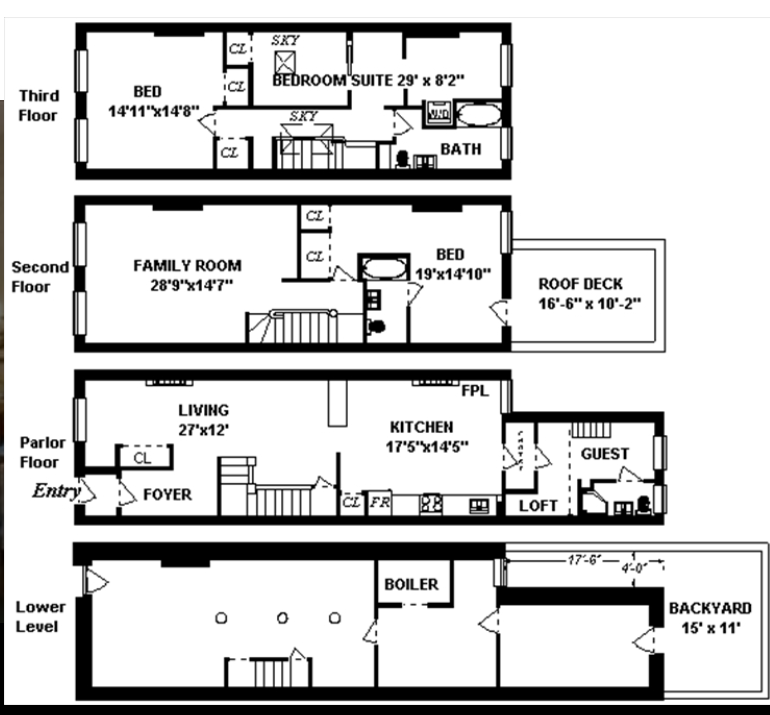

In August 1904, two of Caroline’s neighbors at 103 and 107 East 101st Street petitioned the Board of Health regarding the nightly concerts of 80 or more fat and sassy cats sheltered in the woman’s three-stone brownstone at 105 East 101st Street. “It is not that we object to Miss Ewan’s humane impulses in caring for all the stray and homeless felines of the neighborhood, but the noise of her pets is something wonderful,” the petitioners said. “It is enough to drive a strong man with a newly-signed pledge in the pocket to drink.”

According to petitioners Jacob Thorman and J. Kaplan, “There are bass cats and soprano cats, tenor cats and contraite cats, but there is no feline to drill them and make them sing in unison or harmony. I am fond of good music, but I do not consider eighty cats singing in eighty keys and eighty kinds of time good music.”

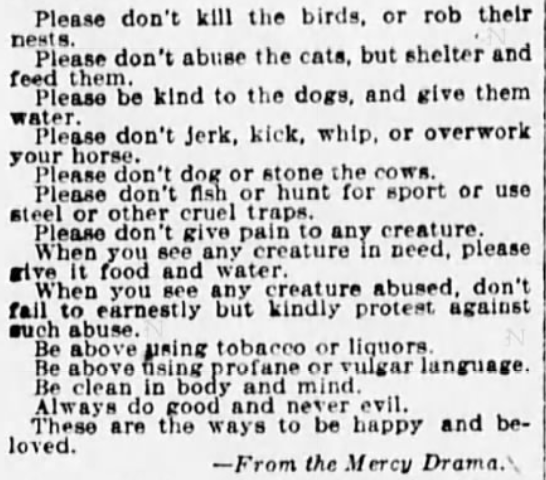

Reportedly, Caroline had moved into the home a year prior. At that time, she had only three cats and three servants. But then she made an offer to the little neighborhood boys that they couldn’t refuse: for every stray, hungry, and homeless feline they brought her, she would pay them ten cents. In return, they had to pledge to be kind to all living creatures and to protect them from cruelty.

Here is the wording that was on the back of pledge card, which also featured a picture of a dog and cat fraternizing. Every boy with a cat received a dime and this card:

In addition to what one neighbor described as “mangy cats,” some of the boys also brought her well-fed kitties that already had homes. So, Caroline had to remind them that she would only pay for homeless cats. By the summer of 1904, Caroline Ewen had anywhere from 80 to 180 cats, as estimated by her neighbors.

According to The Sun, one of Caroline’s aims was to reform bad street cats by bringing them indoors and introducing them to “the joys of gentle domesticity.” To prevent the indoor cats from falling out the windows, Caroline put screens in all her windows.

After restoring the cats to good health, she looked for families to adopt them. Dewey, an all-white cat who looked like “an admiral on the quarter-deck,” was one such former wicked kitty who had learned good manners.

Caroline wouldn’t say how many cats she had, but she did admit she had a lot. She also said that she refused to listen to her neighbor’s complaints, and would continue to rescue and care for starving and homeless cats as long as she wished and without regard to how her neighbors felt about it.

Well, it wasn’t long before a health inspector from the Board of Health showed up at Caroline’s house. At first he told the neighbors there was nothing he could do, but when they all threatened to move if he didn’t deal with their complaints, he told the cat lover that she would have to move.

“Yes, I expect to move,” she told a reporter from The Sun. “I shall go somewhere on the West Side, where my friends are, and where people can sympathize with my love for cats. What harm do my cats do anybody?”

I’m not sure where Caroline Ewen ended up next, but by 1910 she was living at 23 West 86th Street, just to the west of Central Park. In those days, Central Park was a haven for stray cats and dogs, so I wouldn’t be surprised if they ate many of their meals at Caroline’s house.

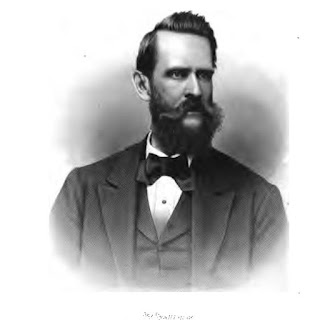

Brigadier General John Ewen

Caroline Ewen was one of four children of John Ewen, a brigadier general in New York State’s National Guard during the Civil War.

Ewen, a civil engineer by trade, took part in surveying and laying out the village of Williamsburg in Brooklyn. During his illustrious career he also served as the chief engineer for the New York and Harlem Railroad, as New York City’s Street Commissioner and, later, as Comptroller. He was subsequently elected president of the Pennsylvania Coal Company (the hamlet of Port Ewen, New York, where the company had a coal depot, was named for him).

During the 1840s, John and his brother Daniel established their country estates on about 150 acres that were once part of the Frederick Van Cortlandt estate in the Bronx (then Westchester County), between Kingsbridge and Riverdale. When John Ewen died at the age of 67 in 1877, Caroline and her two sisters–Louise and Eliza–inherited about $1 million from their father.

Caroline Ewen Bequeaths Her Estate to Stray Cats

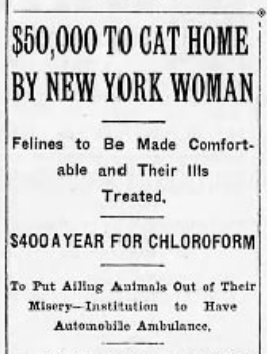

Caroline Ewen died at the age of 73 on April 12, 1913, at her home at 45 West 92nd Street. According to several newspapers, her will stipulated that all but $500 of her personal holdings (cash and real estate totaling about $300,000) go to various societies dedicated to serving homeless and suffering dogs, cats, and other animals in New York, Boston, Philadelphia, London, Rome, Naples, and the Island of Madeira.

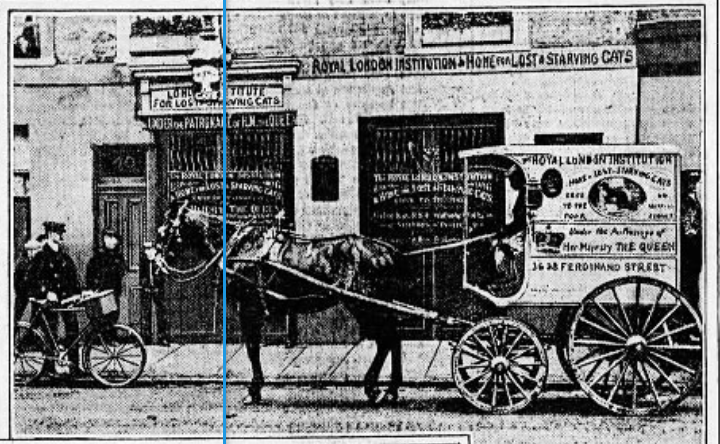

Some of the beneficiaries included the Humane Society of New York City, the Animal Rescue League of Boston, and the “Cat’s House” in London (aka, The London Institution for Lost and Starving Cats).

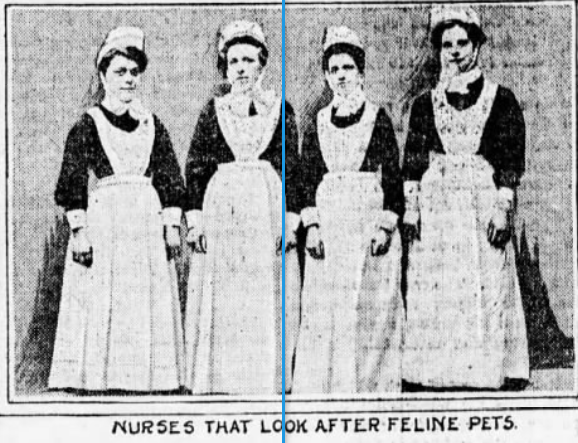

Unfortunately, some of these agencies provided only temporary shelter for cats born outside of the aristocratic class before killing them with chloroform. According to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, for example, the announcement that the Ewen estate had bequeathed $50,000 to the London cat house caused quite a flutter of excitement among the nurses who worked at this facility, but the cats may not have been so joyful:

“Altogether, there is quite a noticeable change in the conduct of the ordinary London cat since the news of this remarkable legacy reached this side. He evidently realizes that a substantial bank balance at the Institution means a curtailment of his liberty and an earlier consignment to the lethal chamber unless he is able to carry about with him evidence of a distinguished pedigree.”

The Ewen Family Estate Goes to the Cats and Dogs

Three years after Caroline died, her sister Eliza offered five acres of her portion of the family estate to the New York City Parks Commissioner, Borough of the Bronx. The deal was that the city had to create a park called Ewen Park in honor of her father, and Eliza had to be allowed to live in her house and have full use of the buildings and grounds until she died. The park was designed in 1935, following her death.

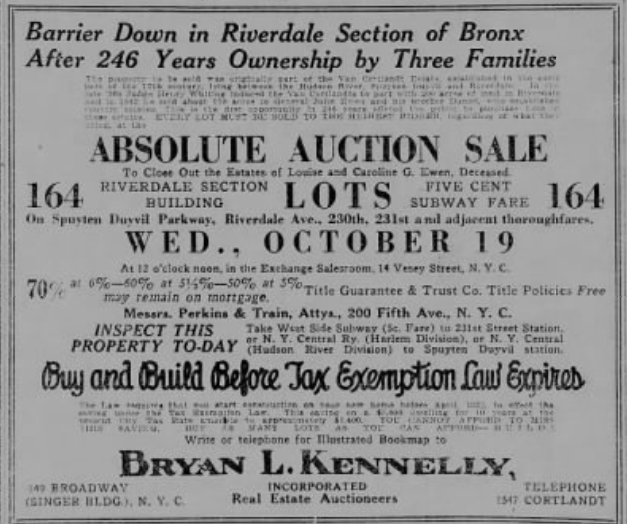

In October 1921, a year after the death of Louise Ewen, 162 lots along the Spuyten Duyvil Parkway (now Manhattan College Parkway), 231st Street, Riverdale Avenue, and adjacent thoroughfares were sold at auction. The sale marked the breaking down of a major barrier in the development of Riverdale by opening a tract of land that had been held by the Ewens and two other families for nearly 250 years.

Per the wills of Caroline and Louise, more than half of the proceeds from the auction sale–$50,000–was donated to the same humane societies that benefited from Caroline’s personal inheritance when she died in 1913.

Several people contested the sisters’ wills, including nephew John Ewen (Eliza’s son), and Otto von Koenitz, an ex-convict and much younger ex-husband of Louise who had once falsely claimed that he was a baron (very long, complex story). The court held the wills of both sisters were valid.

By the way, I do not know how many cats Caroline had when she died, but I do know that her sister Louise adopted her beloved cat, Petie. As the story goes, Caroline was going to have Petie euthanized when she died to prevent him from being mistreated; instead, he lived another seven years with Louise. He was euthanized and buried alongside Louise after she died in January 1920 at her home at 151 West 86th Street.

Now, if only I knew where Louise was buried. There is a Ewen family buried at Old St. Raymond’s Cemetery in the Bronx, but looking at the dates on the gravestone, it appears to be a different family. So this is a still a mystery…

I often walk my dog in Ewen park and have always wondered where the Ewen house was sited. Now I understand why there is the top of a stone wall poking out of the dirt in the dog run. Thank you so much for covering some of the less know parts of NYC.

Jeremy, could you take a photo of that stone wall and send it to me at pgavan@optonline.net? I’d love to add it to my story, but I don’t foresee myself getting into the city for some time. My dad grew up in Kingsbridge in the 1930s-40s, and he said he and his friends used to go to Ewen Park all the time to go sleigh riding and play with their bows and arrows. They didn’t know how to spell it, and there were no signs back then, so they called it You-In Park. I sort of recall him taking me there when I was a little girl many years ago.

Louise Ewen is buried in Old St. Raymond’s Cemetery in The Bronx. See Find-a-Grave entry:

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/search?firstname=Louise&middlename=&lastname=Ewen&birthyear=&birthyearfilter=&deathyear=1913&deathyearfilter=exact&location=New+York+City&locationId=&memorialid=&mcid=&linkedToName=&datefilter=&orderby=

It does not tell where here sister is buried

This is wonderful — thank you! I’m going to add this to the story. And as soon as we’re back to normal, a trip to this cemetery is in order.

Looking more carefully at the dates, I don’t believe this is the same Ewen family. Louise Marie died in 1920, not 1913. And the names of other family members buried at this site do not match the family related to Brigadier General John Ewen. So, the mystery remains.