The Winter Garden Theatre was home to the original Broadway production of Cats from 1982 until the production closed in 2000. But about 50 years before the creepy human cats appeared on stage, the theater was famous for its real cats, Minnie and Miss Frothingham.

Animal mascots on Broadway were quite popular in Old New York–almost every theater in New York City had at least one cat, dog, or monkey mascot. Union Square Jim took top honors as favorite theater mascot cat in the late 1800s, but it was Minnie, the feline mascot of the Winter Garden Theatre, who garnered the most publicity in the twentieth century.

Minnie was even more popular than Miss Frothingham, who was reportedly the feline star of the show at the Winter Garden. Much of Minnie’s publicity was courtesy of New York Daily News columnist John Chapman, who often wrote about the cat’s adventures in his “Mainly About Manhattan” column.

According to Chapman, Minnie arrived at the Winter Garden Theatre in the fall of 1928, which was the year Warner Bros. took over and converted the former theater into a movie house. (The theater returned to a live performance format in 1933). She made her way to the Montmartre Club, which then occupied the second floor of the three-story nightclub space on the 50th Street/Seventh Avenue side of the building.

The nightclub’s cook fed Minnie and made her welcome. The club had lots of mice, so there was lots of work to keep the kitten busy.

The Montmartre folded following the crash of 1929, but luckily, Larry McAllister, an engineer for the Winter Garden Theatre, found Minnie roaming around the deserted club. He took her back stage and fed her. Then he put her in the cellar where she reportedly captured a rat twice her size.

That catch earned Minnie the title of official mascot of the Winter Garden Theatre.

According to Chapman, her number-one fan, Minnie was a lady who never left the building. She never had a husband and she never had children. She did have lots of friends, though, especially among the 40-60 stage hands working at the theater at any given time.

The stage hands also adored Minnie, and they would often bring her food and boxes of catnip. In return, any time she caught a mouse she would leave her kill just outside the stage door as a gift for her friends. If one of her favorite stage hands was transferred, she would sit at the door all day waiting for him to return.

Minnie didn’t care for the show girls, but she did make an impression with actress Fanny Brice of the Ziegfeld Follies, who tried to adopt the cat for her own. Morrie the night watchman would not allow it, as he never let Minnie out of his sight.

The popular Winter Garden Theatre cat was not only adored by Chapman and other humans–it seems that Midnight, the mascot cat for Radio City Music Hall, was also smitten with Minnie. The male cat reportedly “sent” a letter to the Daily News that read as follows:

Could you possibly arrange a meeting between the undersigned and Minnie, of the Winter Garden? I am a bachelor, 2 ½ years old, and I occupy a floor and terrace overlooking 50th Street and Sixth Avenue. I can offer her good grub, as I am fed on calf’s liver, chicken and fish. Sometimes, after a cocktail party in the apartment Roxy built [the private suite designed for Samuel Roxy Rothafel], I get caviar.

Minnie Appears on Stage at the Winter Garden

Although Chapman insisted that Minnie never once walked onto the stage at the Winter Garden during a performance, other reporters told a different story. According to one newspaper, Minnie once walked on during a “mood” song and took a position downstage center. With the attention of the audience centered on Minnie, the number was ruined. Another time she reportedly chased a dog off the stage, which stopped the show.

Once, someone submitted an application for Minnie for the Actors’ Equity Association. She was almost accepted until the association found out that it was a joke. (I wonder what last name was used on the application?)

During theater productions, when she wasn’t on stage, Minnie spent her time in the basement. As soon as the curtain rose at the end of the show (she knew when the curtain was raised because the rigging extended into the basement), Minnie would come upstairs and wait for Morrie by the water fountain near the stage door.

While Minnie waited, the performers would all stop to caress her while exiting the door. Then she would follow Morrie all around the theater as he made his rounds when the theater had closed.

Minnie reportedly made her official Winter Garden Theatre debut in 1933, in a comedic play written by Russel Crouse (of The Sound of Music fame) called “Hold Your Horses.” I find this hard to believe, however, because by this time Minnie was already five years old and no doubt way too big for the part she reportedly played. But according to her pal Chapman, Minnie was used as a prop for actor Joe Cook, who “poured” the cat from a small wine goblet during one scene.

In April 1937, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that Minnie had adopted a kitten. Apparently, Morrie had brought the stray kitten to the theater, never suspecting that Minnie’s maternal instincts would kick in.

One month later, Minnie died following an operation. The very night that Minnie died, a new cat arrived backstage to muscle in on Minnie’s territory. According to Chapman, the Winter Garden crew decided that this cat was not a suitable successor. Minnie was a lady; this cat was not.

Russel Crouse and Miss Frothingham

Following Minnie’s death, show writer and cat fancier Russel Crouse wrote the following letter to the New York Daily News. In the letter, he claimed that Minnie was not the feline star of his show–the real star was his own cat, Miss Frothingham. The delightfully amusing letter read as follows:

“I have just read that Minnie is dead. Now I may speak freely. Far be it from me to speak ill of the dead. Minnie was a nice cat and I liked her. But she had been getting away with murder in the way of publicity for several years, and now that she has gone to the Big Saucer of Milk I think the truth should be known.

Minnie had been claiming that she was the cat that was poured out of the cocktail shaker in “Hold Your Horses,” in which Joe Cook appeared at the Winter Garden several seasons ago. That just wasn’t so. I could have exposed her long ago, but I didn’t have the heart.

The cat that was poured out of the cocktail shaker was Miss Frothingham, who sits before me as I write… Miss Frothingham was born in Boston, where we picked her up from a stagehand for the opening there of “Hold Your Horses.” She was three months old and had been hanging around the alley by the theatre for several weeks—trying to get into a show, she tells me, for her folks told her she had talent.

We brought her to New York, where she suffered the fate of many a promising actress. She ate too much. She finally got so fat she couldn’t fit into the cocktail shaker. So we got a little black cat to succeed her. Miss Frothingham remained at the theatre long enough to slap her successor in the face after his first appearance and then retired—retired to my home where she still lives in the memory of her days in the theatre.

Almost three years ago she confided in me that only a family would make her life complete and that she didn’t want any stage door Johnny for a husband. I got her a husband for a couple of days—a fine upstanding cat named Rockridge Sultan, from the right side of the railroad tracks. It cost me $10, but I understand that Sultan later gave the money back to Miss Frothingham. Anyway, two years ago last Christmas, Miss F. produced a son—and took four encores.

Being born on Christmas day these five children were named Gold, Frankincense, Myrrh, Peace on Earth, and Good Will to Men. They are the nicest kittens you have ever seen, although Miss F. gets pretty sick of them at times. That is due, perhaps, to the fact that they show no desire to go on the stage, being content to stay home and rip up my furniture.

As for Miss Frothingham, she seems quite happy, and whenever she sulks I just take out her notices and read them aloud to her, and that seems to satisfy her. But I know she is still an actress. She likes to bite producers.”

A Brief History of the Winter Garden Theatre

John Randel farm maps.

In 1881, William K. Vanderbilt and a group of investors built the area’s biggest building on the blockfront of 50th Street from Broadway to Seventh Avenue. This property, in an area then known as Longacre Square, had once been part of the large Hopper Farm that spread over both sides of Broadway above 50th Street.

Vanderbilt and his wealthy friends didn’t build a hotel; they built the American Horse Exchange–a place where the elite could depend on high-quality thoroughbred horse trading.

On June 12, 1896, a fire swept through the American Horse Exchange. One stable hand and about 60 of the 265 horses stabled there were killed in the blaze as thousands of people crowded around the building, sometimes blocking horses from escaping.

The New York Times reported that ”crazed animals could be seen dashing blindly about in their terror.” Those horses that were lucky to escape were later recovered from all over midtown.

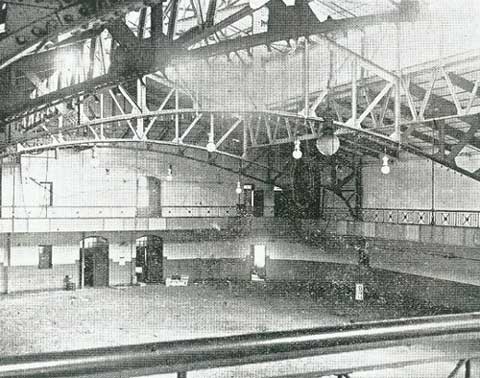

Vanderbilt reconstructed the American Horse Exchange in 1897. According to the New York Times, architect A. V. Porter reused a portion of the surviving walls to create a two-, three- and four-story structure with a high covered ring 160 by 80 feet. The ring was bridged by open truss work; the brick perimeter walls featured round-arched windows as did the original building.

With automobiles becoming increasingly popular, especially among the elite, the Vanderbilt group leased the site in 1910 to Lee and J. J. Shubert for their growing theater chain. By this time, Longacre Square was known as Times Square, and the area was home to several large theaters.

In building their new theater, the Shuberts reused much of the original perimeter walls of the American Horse Exchange as well as the riding-ring truss work for the theater auditorium. They added a temple-style front on Broadway and a three-story nightclub space that extended back behind the old walls on 50th Street to Seventh Avenue.

The Winter Garden Theatre opened March 20, 1911, with “Bow Sing” and “La Belle Paree,” which starred Al Jolson (this was the show that launched his theater career). The theater was completely remodeled in 1922, but six years later the venue switched to film when it was taken over by Warner Bros.

The Winter Garden reverted to live theater in September 1933, which is when either Minnie or Miss Frothingham made her stage debut in “Hold Your Horses.”

Two years after another renovation in 1980, “Cats” opened at the Winter Garden, becoming the longest running show in Broadway history. I’ve never been a fan of the feline-themed Broadway show. But if the theater ever gets a few real cats again, I will be sure to buy a ticket for that.