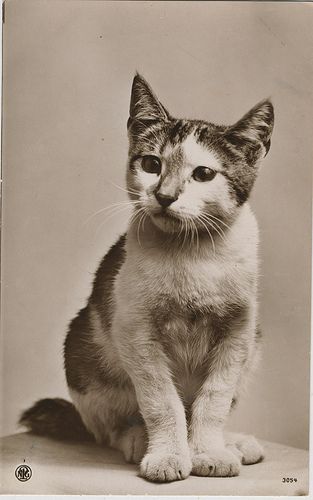

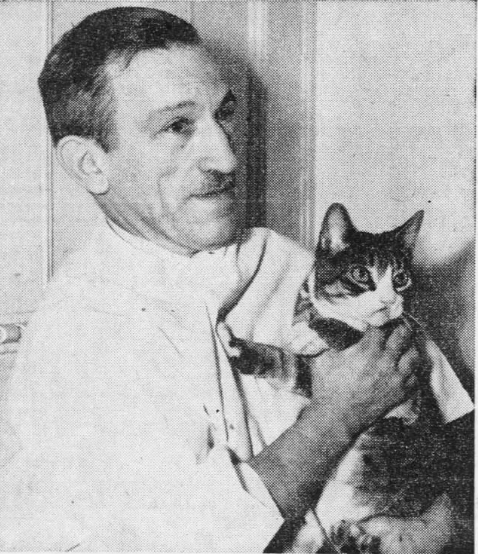

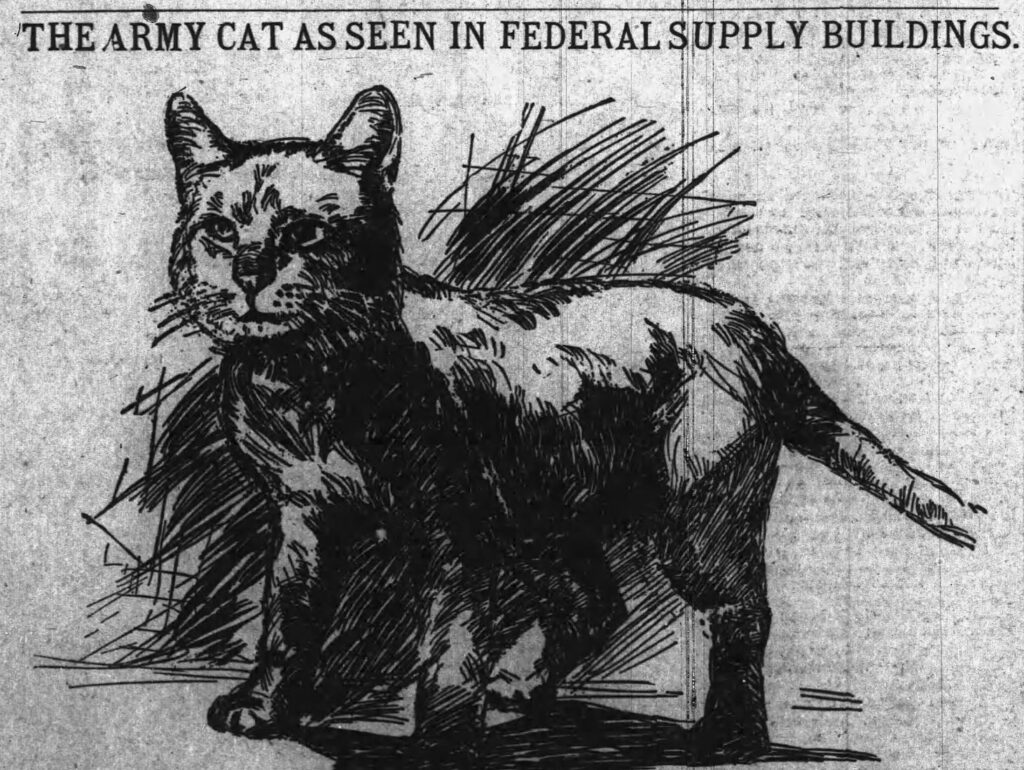

General Weyler was a cat. Not just any cat, but a veteran in a troop of Army cats who served their country in the commissary storehouse in New York City’s Army Building at 39 Whitehall Street.

In Old New York, most warehouses and other large buildings in Lower Manhattan were infested with mice and rats (many still are, of course). Despite its military affiliation, the U.S. Army Building was not immune to the enemy vermin. The best soldiers cut out for the job of extermination were the Army cats.

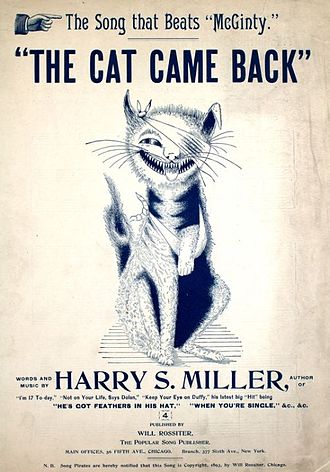

Cats were first employed by the U.S. Army shortly after the end of the Civil War. In July 1898, when this story was reported, America was involved in the short-lived Spanish-American War. During this time, many of the Army cats had names affiliated with Spain and the war.

One of the cats serving in New York City was Queen Regent (named for the queen regent of Spain, Maria Cristina De Habsburgo-Lorena), a female cat who had nine years in the army. There was also General Blanco (named for Ramón Blanco, the Captain-General of Cuba), who was described as “almost as dignified, elusive and unapproachable as her majesty.”

General Blanco was a strong and successful leader in the war on rats. One reporter wrote that “he does vastly more damage than his namesake has yet inflicted upon his enemies.”

Another tough cookie was Alfonso (named for Alfonso XIII, King of Spain), a kitten who was just beginning to earn his stripes when he was struck by a moving truck. Alfonso was expected to survive, but he was placed on the invalid list to give him time to recover from his battlefield injuries.

“Poor littler feller,” one of the men said. “He’s in tough luck, but it’s nothing to what’ll happen to King Alfonso when he’s through running up against the United States.”

The oldest Army cat in the Army Building was General Weyler, whose namesake was Valeriano Weyler, the Governor-General of the Philippines. General Weyler was called Tom before the war, but with 15 years in the service and a “savage disposition,” the men gave him a more appropriate name when the war started.

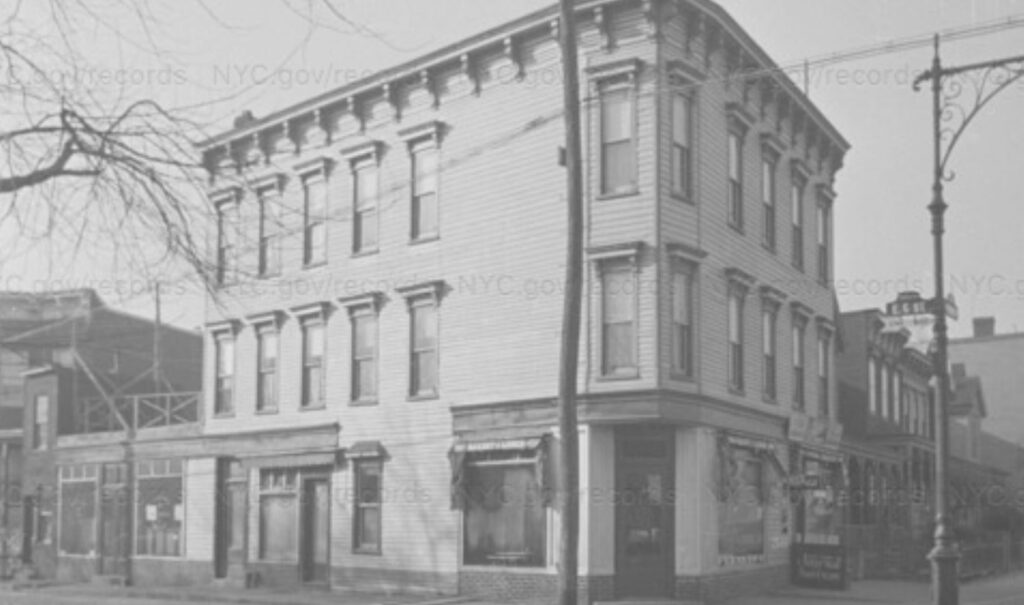

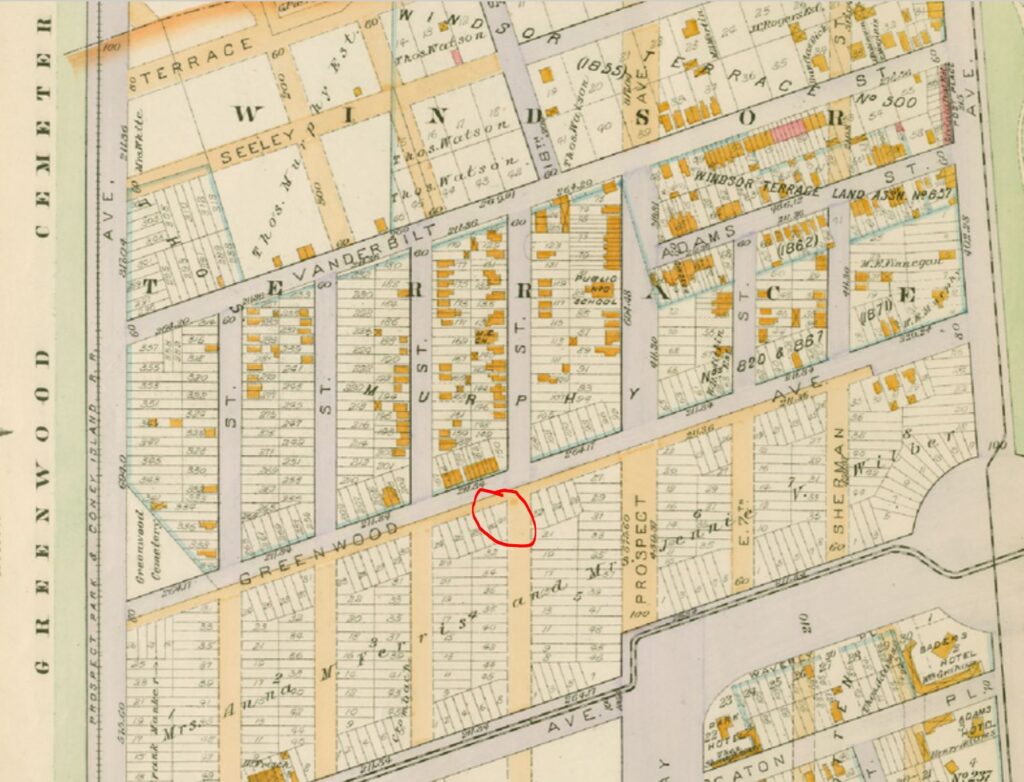

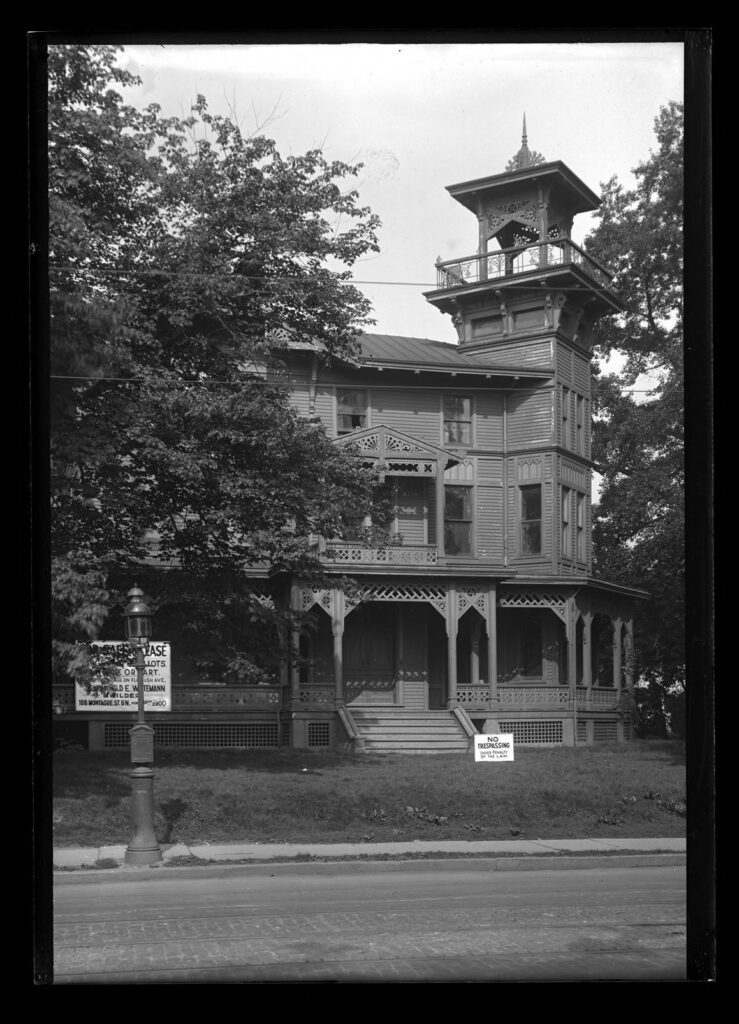

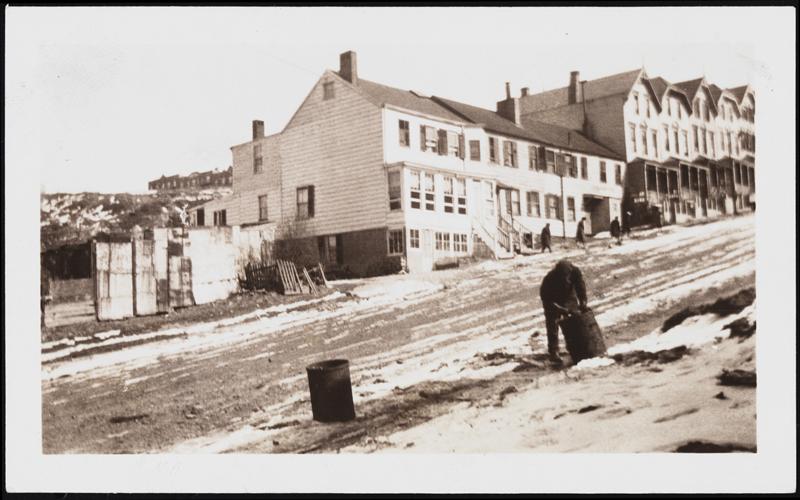

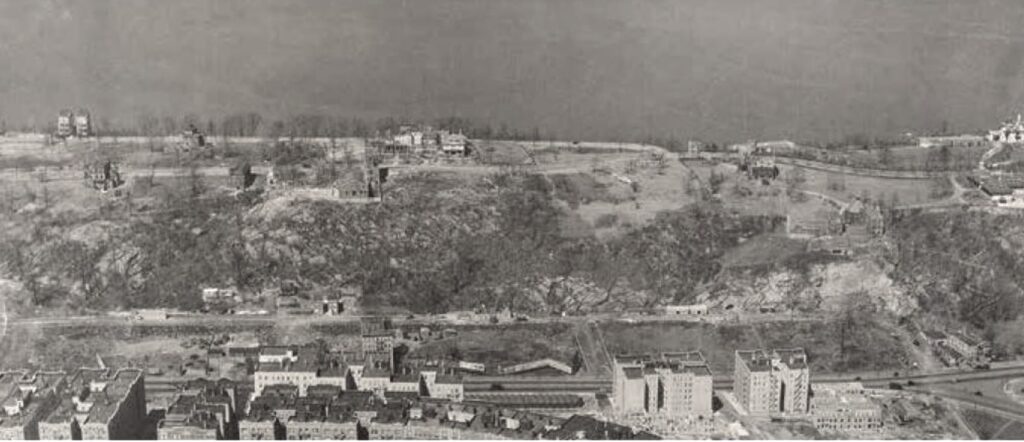

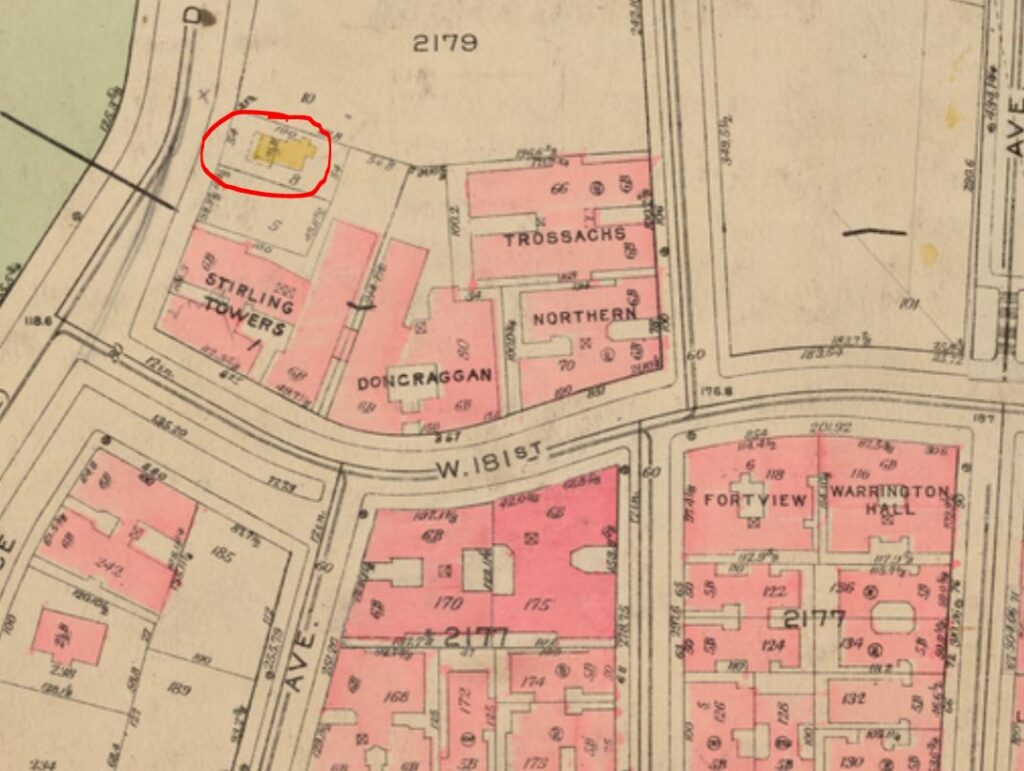

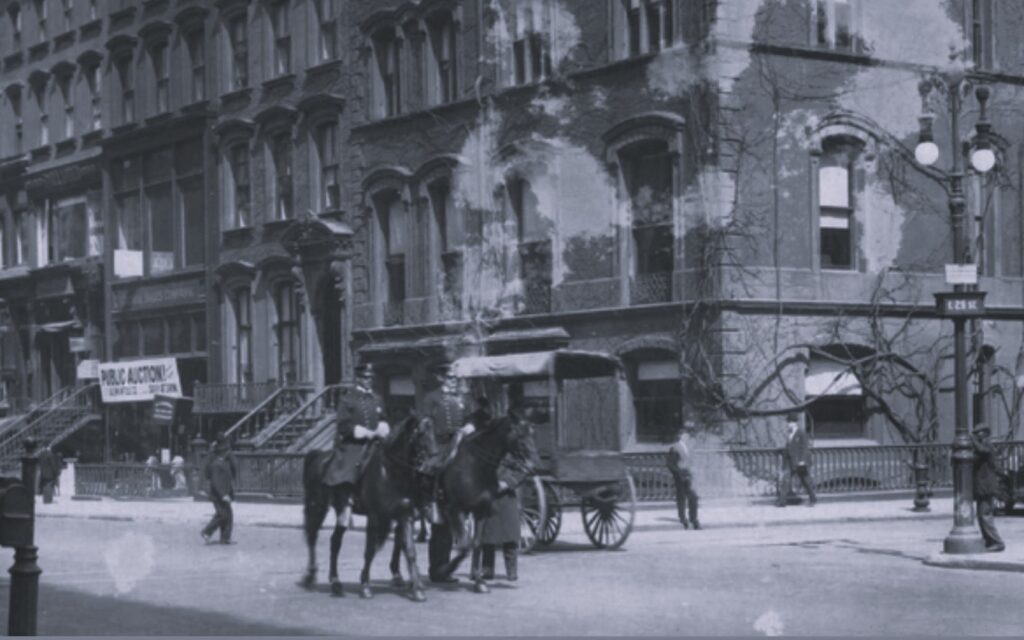

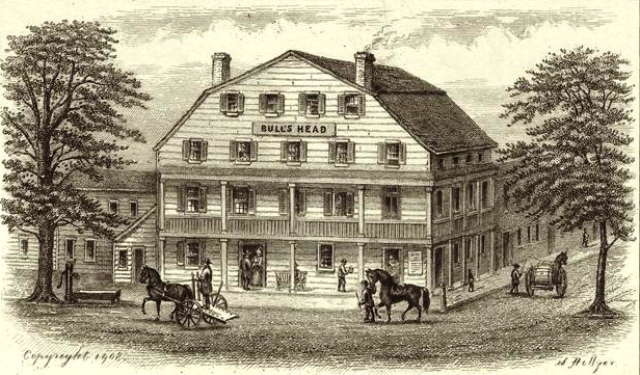

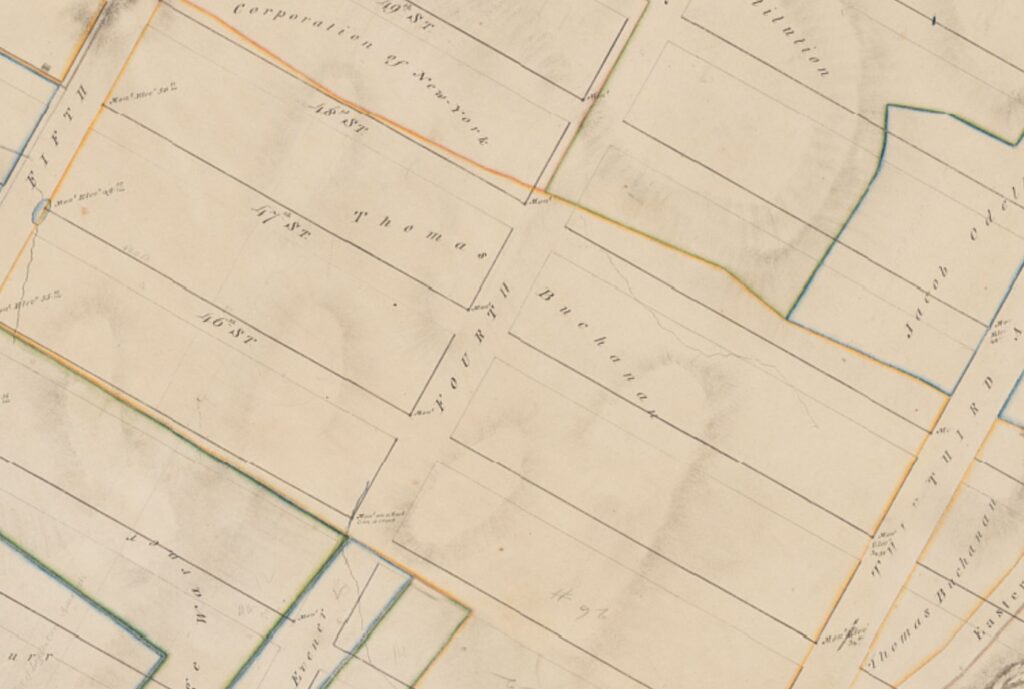

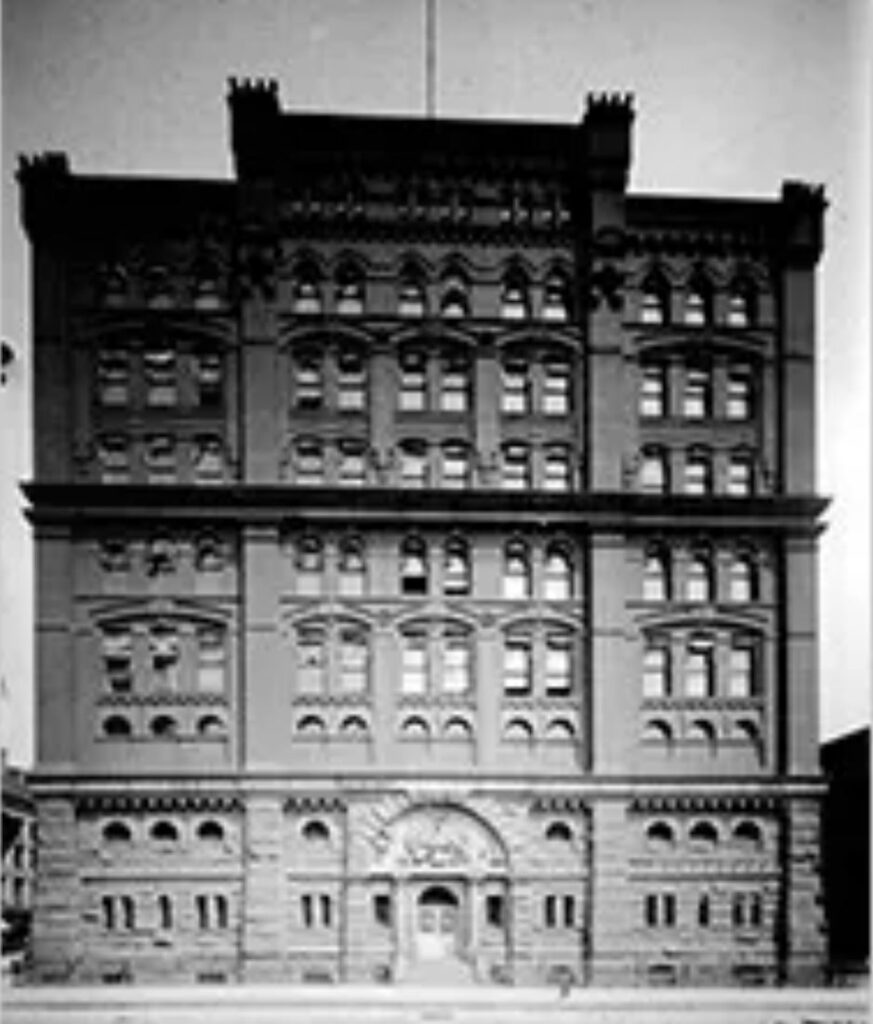

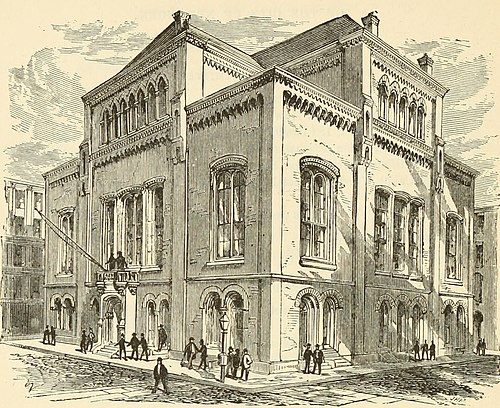

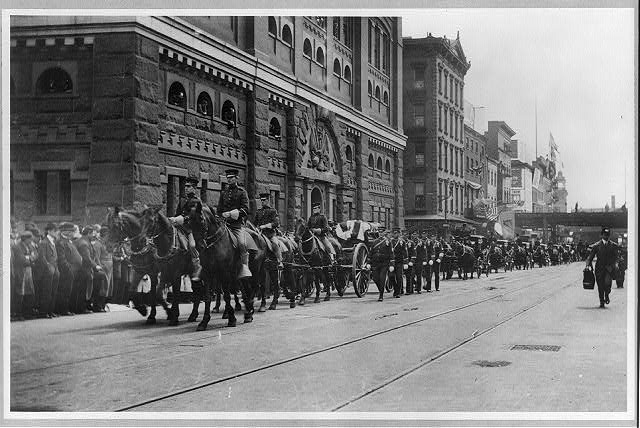

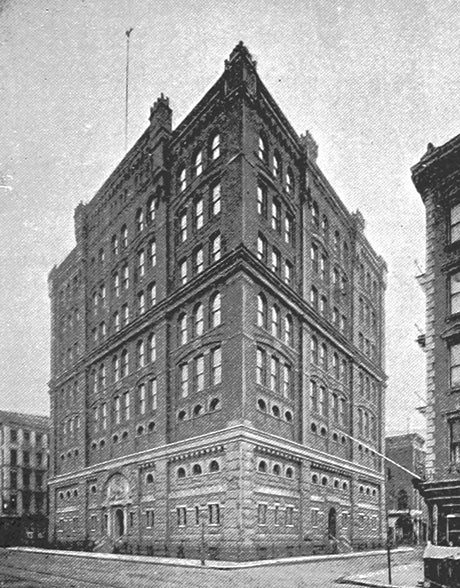

General Weyler joined the army when New York City’s headquarters building was located at the southeast corner of Houston and Greene Streets. He moved into the new Army Building on Whitehall Street when it was constructed in 1887 on the site of the circa 1861 Produce Exchange Building.

Although it’s been described as a “near fortress,” the new eight-story Army Building was riddled with rats and mice that raided the provisions. Night after night, General Weyler would go into attack mode with “undaunted spirit.” As the press noted, “his enemies fell before him, leaving their corpses strewn about as mute witnesses of his prowess.”

Fresh Meat for Army Cats

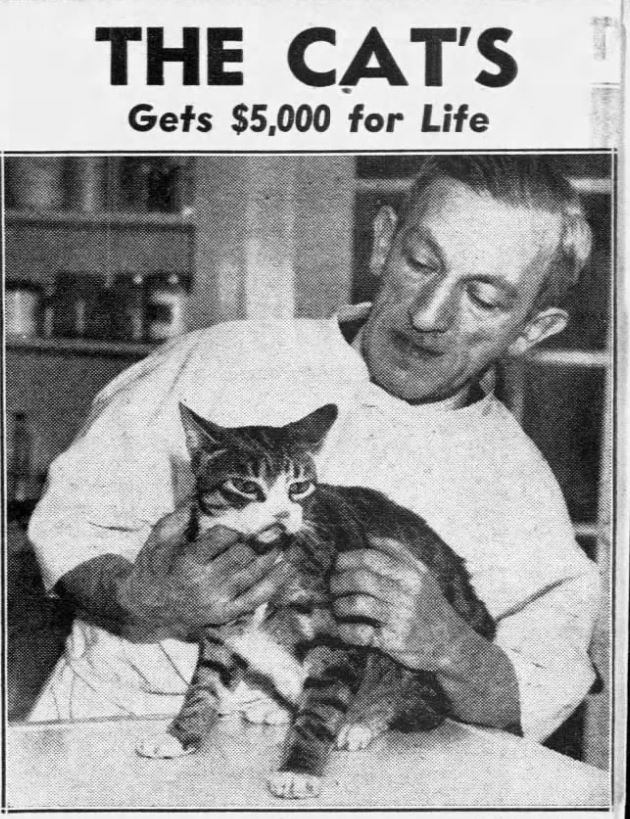

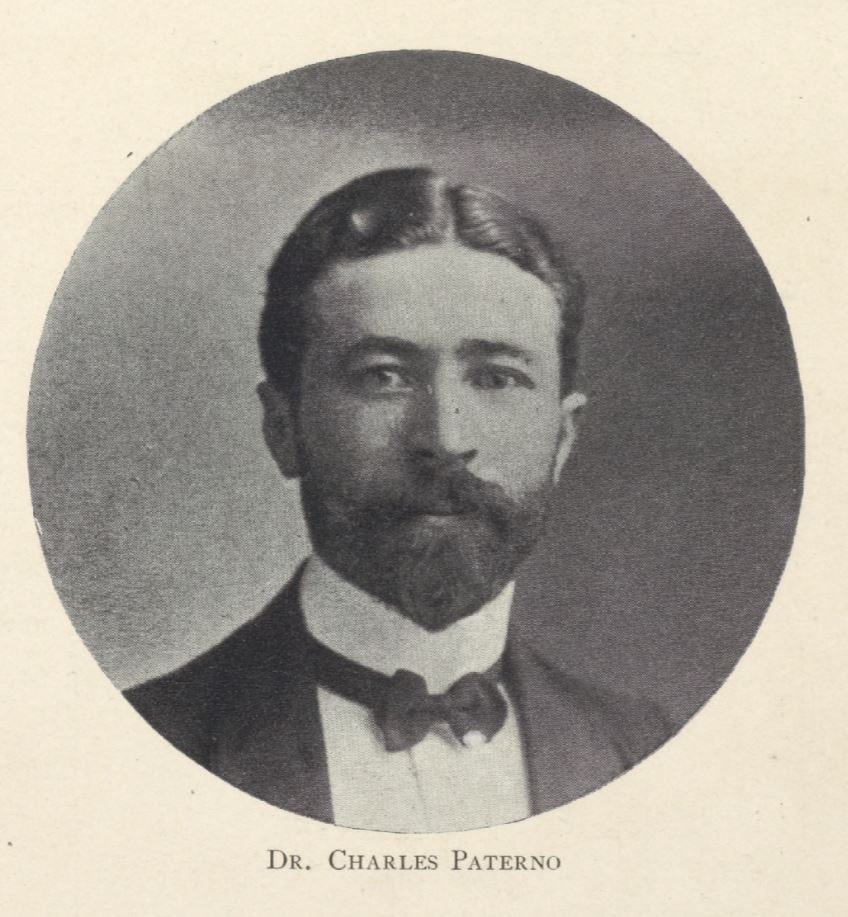

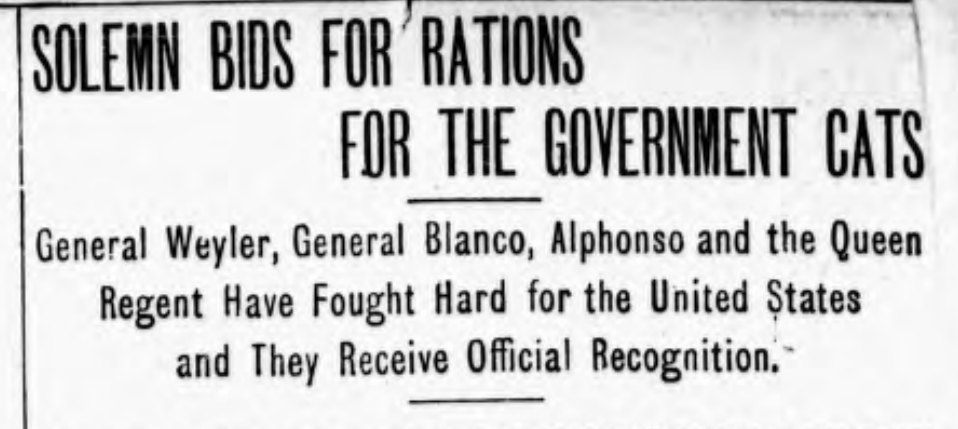

In 1898, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Albert Woodruff, who served as the Assistant Commissary General of Subsistence, advertised that the Commissary Department of the United States Army was seeking sealed bids for fresh beef. The beef would not be for the soldiers on the frontlines, but for the rat- and mouse-killing brigade stationed in the commissary storehouse.

The advertisement stated that the beef was to be “fresh and sound, suitable for feeding cats, bone to be excluded, to be delivered at the contractor’s place of business on such days as may be designated and in such quantities, not exceeding seven pounds per week, as may be required by him.”

As a reporter for the New York Press noted:

The army cats are more particular about their food than even the new recruit. They won’t eat hardtack; it is useless to try to force pork and beans upon them; coffee is not in their line, and they don’t hanker after a canteen. They don’t tire of beef, if it is good, but they are extremely fastidious, and any contractor who tries to work off an inferior quality of meat upon them will find himself in trouble.

The Army cats received their meat ration every evening, just before the men left the building. The one pound of beef allotted to the Army Building each day was cut into small pieces and placed on tin plates. Sometimes the employees would also share their milk with the cats.

According to a report in the The New York Times, the cats cost the Federal Government only five cents a day while saving the government hundreds of dollars in supplies a year (the Federal Government also had a budget to purchase meat for the post office cats). Every military commissary storehouse across the country had from one to five cats to keep the rats in check.

In 1898, General Weyler was ready to retire. The dampness of the Army Building cellar had gotten into his joints, causing rheumatism that made him too stiff to move easily. He spent much of his time laying in a sunny doorway.

With the general on the retired list and little Alfonso still recuperating, the men said they would have to get some more feline recruits. They had a family of kittens on reserve, but as the men explained, they couldn’t wait for them to grow up, so a few older cats would have to be drafted to serve their country.

The Final Years of the Army Building

The day after Pearl Harbor was attacked in 1941, patriotic men flooded the Army Building to sign up for the army. But during the Vietnam War, many protests against the war took place in front of the building. In 1967, Dr. Benjamin Spock, the poet Allen Ginsberg, and 262 other people were arrested in an antiwar protest outside 39 Whitehall Street.

During the Vietnam years, young men who had been drafted received their physicals at 39 Whitehall, which was then serving as an indoctrination station. In his song “Alice’s Restaurant,” Arlo Guthrie described the Army Building as the place where you got “injected, inspected, detected, infected, neglected and selected.”

In 1968 and 1969, terrorists set off bombs at the building; however, the New York Times reported in 1972 that the damage had been minimal. That year, the Army moved from its fortress on Whitehall Street to new offices in the Federal Office Building at 201 Varick Street.

In 1978, Fraydun Manocherian purchased 39 Whitehall, with plans to renovate the building for a branch of his New York Health and Racquet Club. He originally planned to preserve the eight-story building and convert the upper floors into apartments.

Sometime around 1983, Manocherian began demolishing the building without a permit. The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission protested, but the demolition had already caused too much damage to save the building.

The building was extended to 17 stories and the façade was covered with a glass skin. It also received a new address: 3 New York Plaza, aka 2 Water Street, 26-30 Pearl Street, and 39-41 Whitehall Street

Today the building is home to the New York Health and Racquet Club and about 100 luxury apartments.

NYC Cat Museum Pop-Up: Get Your Tickets Meow!

The future NYC Cat Museum and the Museum of Interesting Things are co-hosting a pop-up event on Sunday, May 19, from 7-10 p.m. at The Loft at Prince Street, 177 Prince Street.

The event will feature cat art, cat books, cat board games, cat music, and more. Each attendee will also receive a free raffle ticket for a chance to win a cat travel pack and a signed copy of my book, The Cat Men of Gotham!

Click here for more information and to order your tickets. (Sadly, I will not be able to attend the event as I am having surgery on my foot earlier that week.)