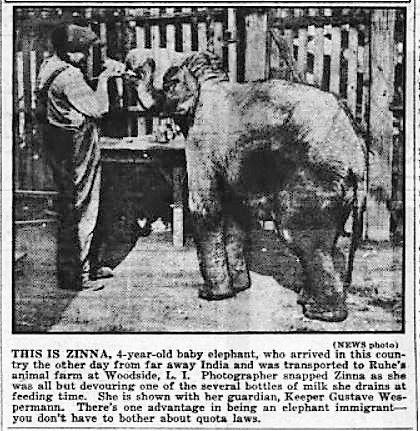

Woodside has been uncomfortable ever since the wild animal farm, as it is known locally, was opened about a year ago. Every woman in the place has predicted that the animals would escape some dark, cold night and wipe out the town, devouring buildings and inhabitants. These predictions came near becoming true on Monday night… Every one trembled as word was passed from house to house, ‘The Ruhe wild animal farm has broken loose and we shall all be eaten alive.’–Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 23, 1905

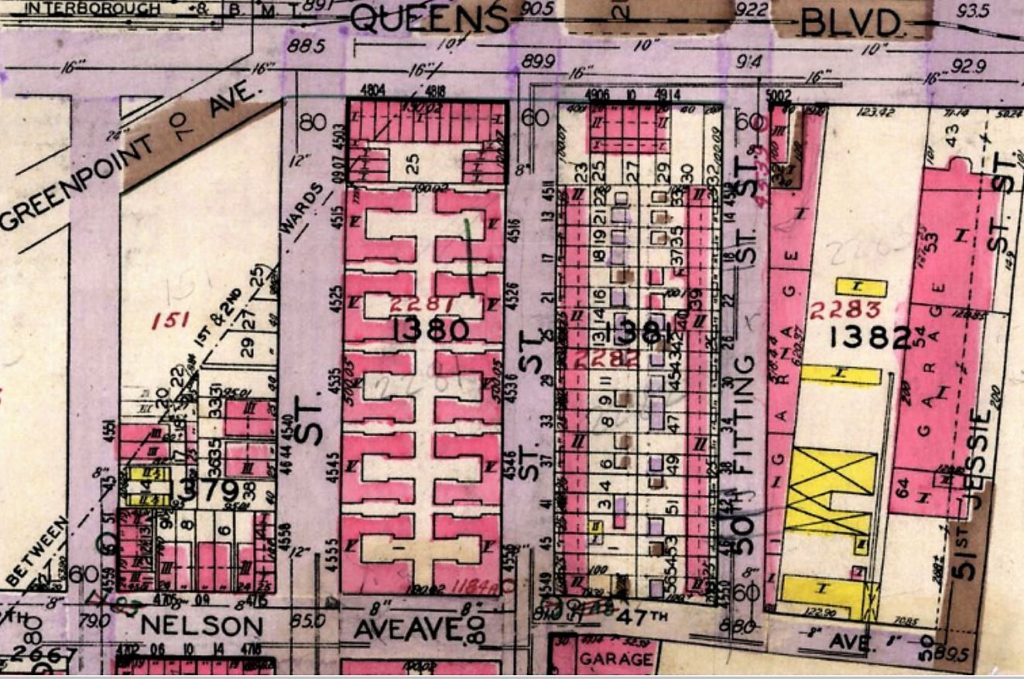

It wasn’t a cold night, the entire population of the animal farm did not escape, and the town wasn’t devoured. But it was probably dark when 10 elephants from the Ruhe Wild Animal Farm at 50-15 47th Avenue in Woodside, Queens, broke lose from their wooden enclosures and went trampling and trumpeting through the thick woods surrounding the farm buildings. As news of their escape spread, young boys gathered around 47th Avenue, Queens Boulevard, and 50th Street to watch as the animals’ caretakers rode around on horseback carrying elephant hooks, spears, ropes, and other tools.

Eventually all the elephants were rounded up and placed back in their enclosures. But it was a long time before sleep returned to Woodside (word is, there was a lot of activity at the local saloons that night).

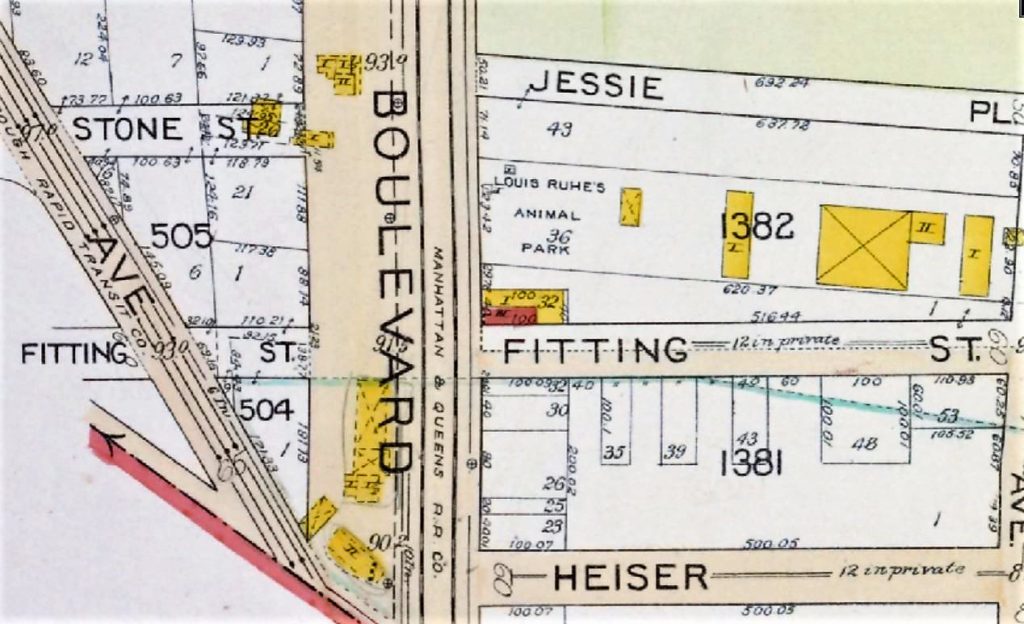

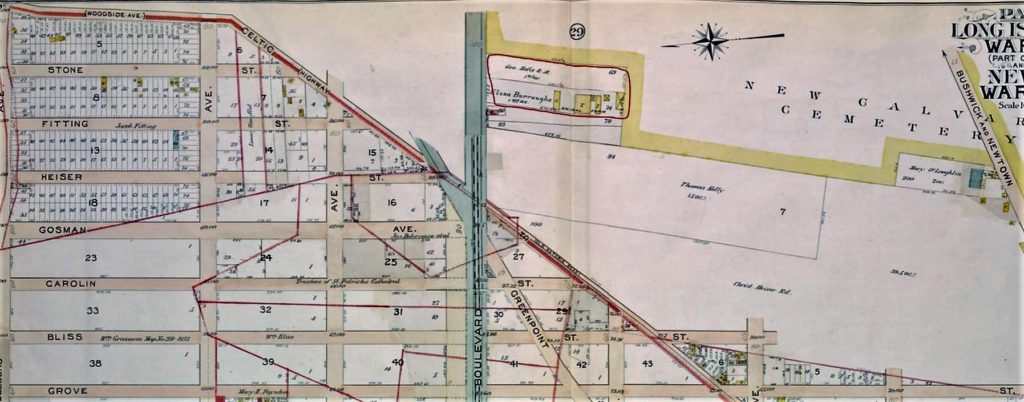

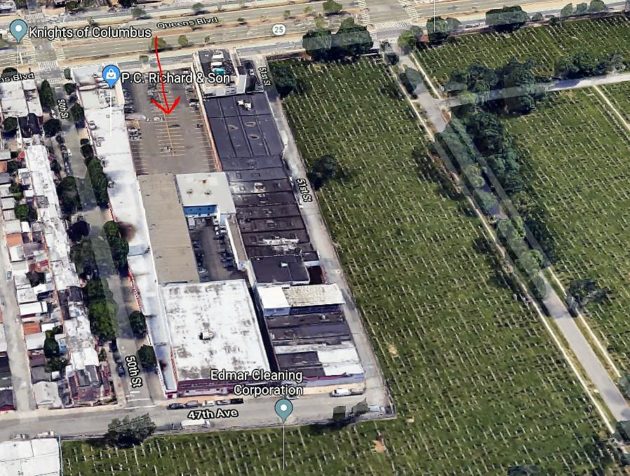

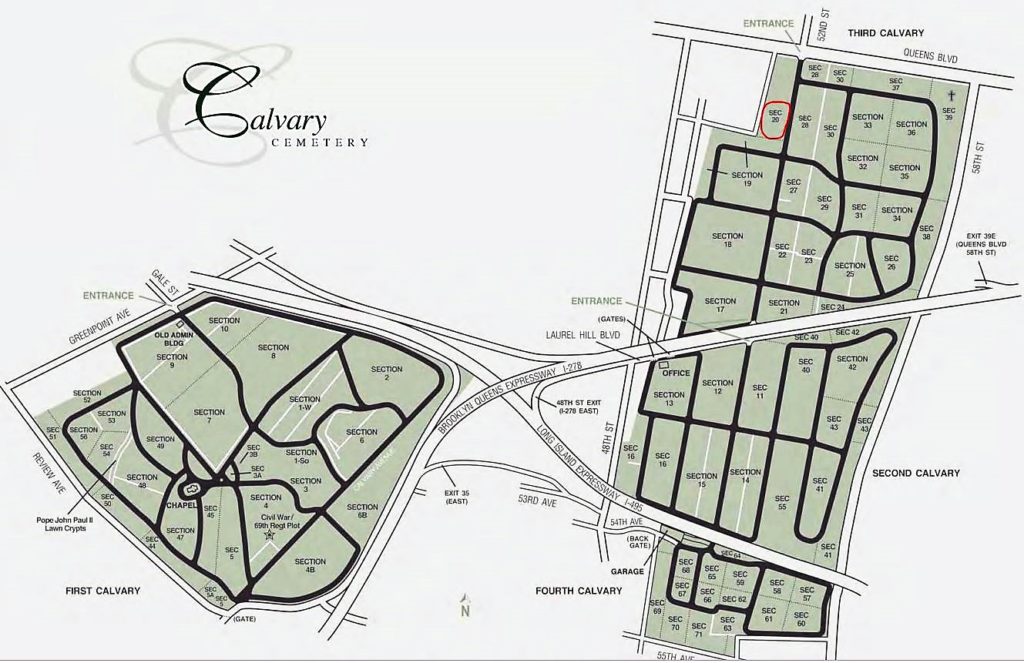

Yes, this was Woodside Queens, adjacent to the Calvary Cemetery on Queens Boulevard, where a giant PC Richards electronics store and parking lot now stand. Amazing what 110 years can do to a place.

The Ruhe Wild Animal Farm: 1904-1959

The Ruhe (pronounced Roo-ey) Wild Animal Farm was just one branch of Louis Ruhe & Sons, a large animal trading company founded in Germany by Ludwig Ruhe in the 1800s. Ludwig started out importing small birds on a commercial level in 1830; he was also a famous hunter of wild animals, which he started selling in Germany in 1856. The family also had a menagerie at Alfeld on the Leine River in Germany.

Ludwig’s son, Louis Ruhe, came to New York sometime around 1868. Louis and his son Heinz reportedly had a warehouse on the Bowery and an office on Broadway. Two other sons, Herman and Ludwig (Louis), continued to run the business in Hanover, Germany, which is where the family operated a large zoo.

Another son, Bernard, who had started capturing wild animals when he was 19 (and who had a baby leopard as a pet when he was a child), came to America in 1881. He operated a bird store on Grand Street in the early 1900s and later owned a four-story building at 351 Bowery, where he kept snakes, monkeys, birds, and other animals.

From the late 19th century to the mid 20th century, the Ruhe Wild Animal Farm in Queens served as a distribution center, where thousands of wild animals from Asia, Central and South America, and Africa would go through quarantine and spend a few weeks before being shipped to zoos, circuses, and movie production companies throughout the United States.

The company also supplied animals to wealthy individuals who wanted an exotic bird, zebra, camel, or other large animal for their private menageries and aviaries.

Four 28 years the menagerie has been there, at the edge of Calvary Cemetery, fronting on Queens Boulevard near 50th Street, yet thousands of persons pass by it every day without knowing that they are within springing distance (except for the barriers of wood, steel and barbed wire) of lions, tigers and other public enemies. A high fence of heavy wire surrounds the three-acre zoo, with its barns, runways and aviaries for its furred and feathered citizens.”–Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 3, 1935

From Fear to Pride in Woodside

When the Ruhe Wild Animal Farm first opened in about 1904, the Woodside residents were terrified. Parents kept their children off the streets and adults of all ages looked ill at ease whenever they walked near the farm. The grove in which the farm stood had once been a quiet place frequented by lovers; now after nightfall it was the least popular place in what was then still considered a quaint and quiet village.

“The roar of the animals sometimes after dark gets on your nerves, if you are walking over by the grove. I never walk there any more,” one resident told a reporter in October 1905. “The noise is like thunder and lightning to me; it makes me shiver.”

About a year after the farm opened, though, the villagers appeared to be much more comfortable with the fact that so many jungle animals were in their midst. They were proud of their menagerie, and loved showing visitors the farm.

Whenever a new animal arrived, the villagers would come out to pay their respects. When animals were sold, they mourned the loss “as they would the loss of some respected and old time citizen.” As one reporter noted, “Pride and interest have taken the place of fear.”

In early years, the residents of Woodside were allowed to help feed the animals; the people were a little too generous with the food so the Ruhes eventually had to put up a fence and place a placard on the gate that read “No Admittance.” During feeding times, the neighborhood boys would climb onto tree branches to watch from a distance.

The Ruhe’s hired up to 400 men in all parts of the world to help capture wild animals and exotic birds. They also hired a woman named Semona Ariadne Konigsdorfer to work as a trainer for the new animals at Woodside. Semona’s father had owned a circus in Germany and she started training dogs and horses when she was only nine years old. At Woodside, the 32-year-old trainer worked with tigers, llamas, panthers, leopards, and lions.

The War Years at the Ruhe Wild Animal Farm

During World War I, manager Ernest Seigfried warned zoos and circuses that the war would probably cause a shortage of elephants in the United States. “In other years we have always had from ten to twelve elephants at this time of year,” he told a reporter. “This year we haven’t any. With the approach of the circus season we have just received orders for 35 elephants, but we cannot fill one of the orders.” According to Ruhe, the elephants were each worth $1500 or more.

Wartime shipping troubles during World War II forced the Ruhe family to domesticate their little wild animal kingdom by raising chickens and hens to aid in the wartime shortage of eggs and poultry. Many of the animal enclosures and runs were converted to house about 3,000 hens, a large flock of ducks, and other domestic fowl.

The Elephant Wedding Gift

When Bernard Ruhe’s daughter Elsie (perfect name) married Carl F. Strohm in 1923, Bernard gave her a baby elephant as a gift.

“An elephant is more valuable than diamonds and more substantial than cut glass or parlor furniture,” Bernard said, explaining that not only was an elephant a good pet, but it was also a good investment since it could be sold for a lot of money when it got bigger.

The five-year-old elephant was originally cared for at the farm by Ernest Siegfried’s daughters, Erna and Sophie. Reportedly, there were plans to baptize the elephant by splattering her forehead with a mud pie (you can’t make this up).

When the bride and groom returned from their honeymoon, the elephant was moved to their home at 4758 Ford Avenue (today’s 79th Place) in the Forest Park section of Queens, where it was kept in a special fenced-in yard

The Deadly Fire at the Ruhe Wild Animal Farm

On January 8, 1959, fire swept through a one-story building at the farm, burning almost 60 animals to death. At least 40 monkeys, five tortoises, three burros, a llama, two Cape hunting dogs, four pigeons, a black-necked swan, a viper, a vulture, and six geese succumbed to the blaze.

According to news reports, 30-year-old farm manager Heinz Ruhe, who lived on the grounds with his wife, Gerda, was awakened by the smoke at around 1:25 a.m. He ran downstairs and tried to enter the burning menagerie, but he was beaten back by the flames and the fumes.

Although the firemen were able to save a building that housed 250 birds and a pair of baby gorillas, as well as another building housing 100 animals that had been acquired by Sloan-Kettering Institute for cancer research, the total loss was about $23,000.

The following year, Heinz and Luiz Ruhe opened the Lynwood Baby Zoo at Lugo Park in California. The site of the Ruhe Wild Animal Farm in Woodside was replaced with a parking lot and a 1.5-story warehouse building that is currently occupied by Edmar Janitorial Store.

The New Calvary Cemetery

The Ruhe Wild Animal Farm was located across the street from the New Calvary Cemetery (the third section of the new cemetery, to be exact). This section of the large cemetery comprises 84 acres, and was opened on September 7, 1879. This land had once been part of the old Burroughs, Dunn, and Peebles farms in what was then called Dutch Kills.

According to an article in the New York Herald, the property had actually been purchased in 1870, even though there was no immediate need for additional burial sites at that time. In order to avoid paying any further taxes on the land, the Trustees of St. Patrick’s Cathedral mapped the old farmland into two large lots. Then they interred a body on each side of the shell road (called the Newtown Turnpike) that divided the lots, thereby establishing their use as a proper cemetery. (Those poor souls who were buried alone and used for a tax write-off.)

During the blessing of the cemetery in 1879, Vicar-General William Quinn of the Archdiocese of New York firmly stressed that the Catholic cemetery was for the burial of Catholics only. No one having had a Protestant burial service performed could be buried in the cemetery. No members of a secret order could be buried there, nor an ex-communicant, a person who committed suicide or other gross sin, or a drunkard for that matter.

Apparently, a Roman Catholic family that owned a lot in the Old Calvary Cemetery was in the process of suing the Trustees at this time for refusing burial in the graveyard. According to news reports, the patriarch of the family, Dennis Copper, was a Freemason, and had therefore violated one of the regulations of the church.

The church refused to allow his burial at Calvary, even though Dennis’ wife, mother, and several children were already buried in the family plot—his funeral procession was actually stopped at the entrance to the cemetery and forced to leave. The case went to the state Supreme Court, where Judge Westbrook ruled in favor of the Copper family.

Vicar-General Quinn was buried at Calvary Cemetery in April 1887. I wonder if some elephants came to visit his grave site in 1905?