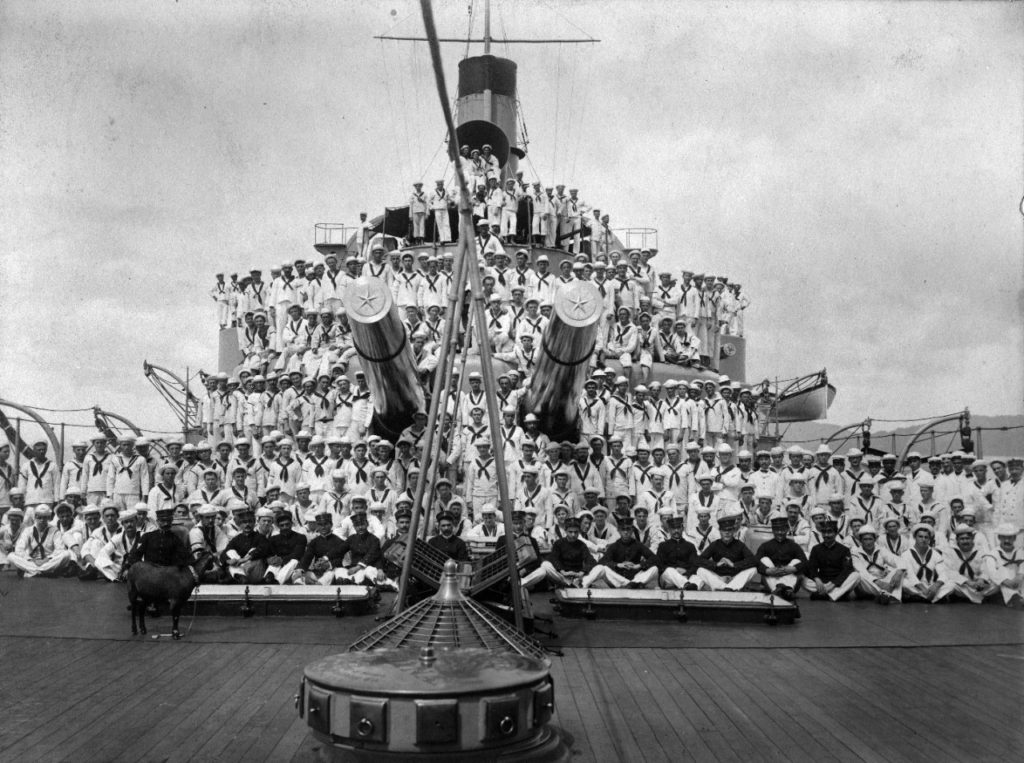

There was much sorrow and indignation among the men on board the USS Indiana on April 27, 1903. That day, there were about six men on the battleship sick list. C. Buster, the battleship cat, was also on the sick list.

“C. Buster!” the ship’s surgeon called out. Letting out a plaintive meow and hopping on three legs, the battleship cat responded to the doctor’s summons. Not able to explain his injury, the cat held up his paw and allowed the doctor to examine it.

According to the story, C. Buster had gotten into the middle of a mix-up between two of the sailors while the battleship was moored at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. One of the men threw a boot at the other, and when the soldier ducked to avoid getting hit, the boot hit the cat instead.

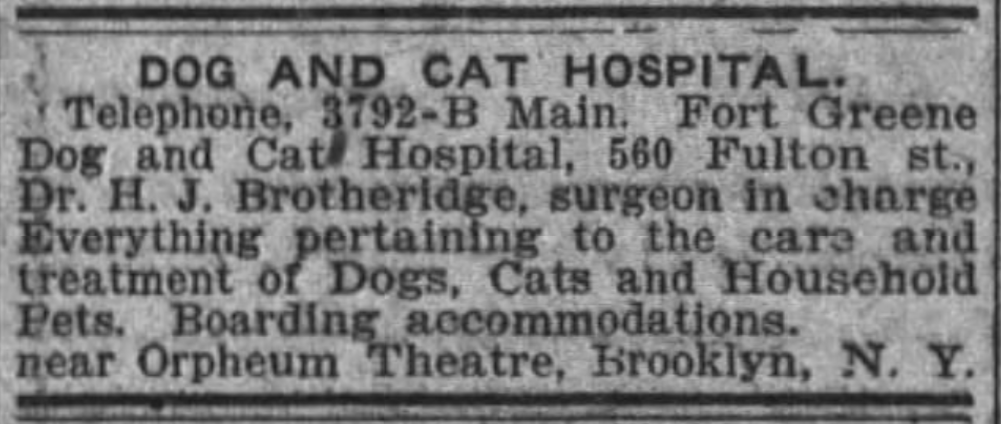

Despite the hundreds of cats that lived and worked at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, there was no facility to treat cats and dogs at the naval facility. So, one of the stewards wrote up medical transfer papers for a cat and dog hospital on Fulton Street in Brooklyn. Commander A.C. Hodgson, the second-in-command officer who owned C. Buster, took the battleship cat to the hospital to have his leg set by Dr. Herbert Joseph Brotheridge.

C. Buster’s visit to the Fort Greene Hospital for Dogs and Cats was not the first time a mascot of the USS Indiana required treatment there. The ship’s dog, Rogers, was also treated by Dr. Brotheridge for a diseased hind leg.

Sadly, the doctor had to amputate Rogers’ leg. Although it took Rogers a while to get used to his condition, he was eventually able to hop around on three legs without difficulty. C. Buster fully recovered from his broken leg.

The ship also had a brindle goat at this time named Nancy. There are no reports of Nancy requiring veterinary care at the animal hospital.

A Brief History of the Fort Greene Hospital for Dogs and Cats

Born in 1875, Dr. Herbert Joseph Brotheridge graduated from the New York College of Veterinary Surgery in 1894. He opened his first animal hospital in 1895 in his hometown of Freeport, Long Island before setting up shop in Brooklyn.

Sometime around 1901, Dr. Brotheridge established a practice for dogs, cats, and other small domestic animals in a one-story brick building on Cumberland Avenue, just north of Myrtle Avenue (now the site of the Walt Whitman Houses, completed in 1944.) In 1903, he opened a pet hospital at 560 Fulton Street, near the junction of Hudson and Flatbush Avenues. Next door was the new Orpheum Theatre, built in 1899-1900.

According to an article about the hospital published in 1903, the hospital was a novel idea in that it specialized in family pets as opposed to horses and livestock. The first-of-its-kind facility featured a reception room or parlor in the front, where wealthy clients brought their pets, and an operating room with marble tables, tubs, and washstands in the back of the building.

On one side of the main room were beds for dogs and cats arranged against a wall in “individual wards,” and on the other side were cages for birds. A metal gutter attached to each tier of wards drained into the sewer, allowing for quick and sanitary cleaning. There was also a bath where each animal was bathed upon arrival; weekly baths were provided for those animals spending longer periods of time in the hospital.

“The clients display as much anxiety over their sick as would humans waiting in the reception room or a hospital or infirmary,” Dr. Brotheridge told a reporter in 1908. He explained that most of the ailments he treated were stomach related for the dogs and skin or throat related for the cats. Many of these ailments were the result of being overfed by their wealthy owners.

“After Fido has been fed on caramels and sweet cakes until he’s so bloated he can hardly walk, his lady finds he’s sick one morning,” he said. “She’s alarmed and she offers him more candy and cake and when Fido refuses she hurries him here. Some of them cry as if they were babies they were bringing. Some of them cry a good deal more, I guess.”

Asked which animal made the best or worst patients, Dr. Brotheridge said cats were the most sensitive of all patients as they were “cross and crotchety.”

Although Dr. Brotheridge was known as a cat and dog specialist, he made the news for his role in the execution of Topsy the elephant, who was electrocuted by none other than Thomas Edison in January 1904. Dr. Brotheridge supervised the horrific event and even fed Topsy the cyanide-laced carrots before Edison pulled the switch.

The pet animal hospital didn’t last long, as Dr. Brotheridge became very active in the military, serving as a veterinary sergeant with the National Guard from 1902 to 1908 and as a captain in the Veterinary Reserves Corps during World War I, where he was stationed at Fort Oglethorpe in Georgia.

By 1910, the animal hospital was gone and a new billiards academy and bowling alley had moved into 560 Fulton Avenue. The academy and alleys were built by Herman F. Ehler, a Brooklynite, who was the kingpin of bowling, having built a chain of bowling alleys in Brooklyn, Manhattan, Pittsburg, Buffalo, Cincinatti, Chicago, Newark, Trenton.

The Orpheum Billiard Academy and bowling alleys occupied this site through the mid-1940s.

On August 28, 1932, Dr. Brotheridge and his wife Gertrude were walking across Ocean Hill Boulevard in High Hill Beach (a small community at present-day Jones Beach that existed until 1939) when they were struck by a vehicle driven by Fred Haupt. Mrs. Brotheridge was killed instantly. Dr. Brotheridge died at Brunswick Hospital in Amityville the next day.

Haupt was arrested and charged with second degree manslaughter. The Brotheridges were buried at Amityville Cemetery.