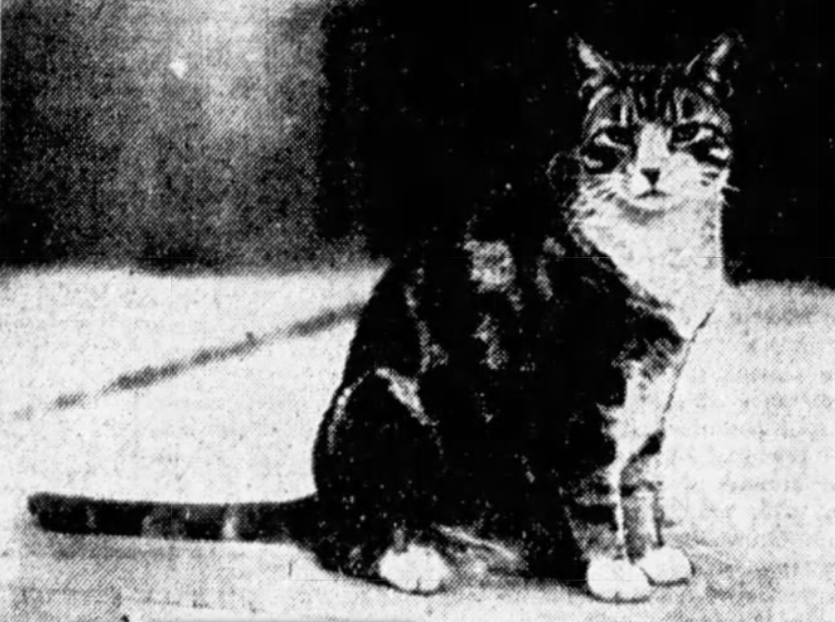

In 1903, one of the most popular dog-and-cat dynamic duos of the FDNY were Dan and Nickie* of Engine Company No. 65. Dan was a well-loved coach dog (possibly a Dalmatian), and Nickie was a jet-black cat who was the pet of Captain Hawk.

According to the nationally published news story, Hawk rejoined the FDNY as an assistant foreman of Engine Company 29 on Chambers Street shortly after the Spanish-American War of 1898. One day, a disheveled stray cat followed him into the station. The cat was incredibly affectionate and intelligent, so the men agreed to adopt him as an unofficial member of the company.

When Hawk was appointed captain of the newly organized Engine Company No. 65 on West 43rd Street, the cat was “officially transferred” to the new company. FDNY Commissioner John Jay Scannell, the first fire commissioner of the new consolidated New York City, gave the transfer his official seal of approval.

Not much is known about Nickie, except that he always slept in Hawk’s bed at night. Whenever an alarm sounded, he would jump out of bed faster than the captain. (Apparently, experience taught him to respond quickly—it was better than getting tossed to the floor.)

The cat would then rush for the first step of the iron stairs and curl up into the smallest possible space to avoid the onslaught of stomping feet. From this vantage point, he would watch as the horses were hitched up and the engine rolled out.

Cappy, the Beloved FDNY Dalmatian

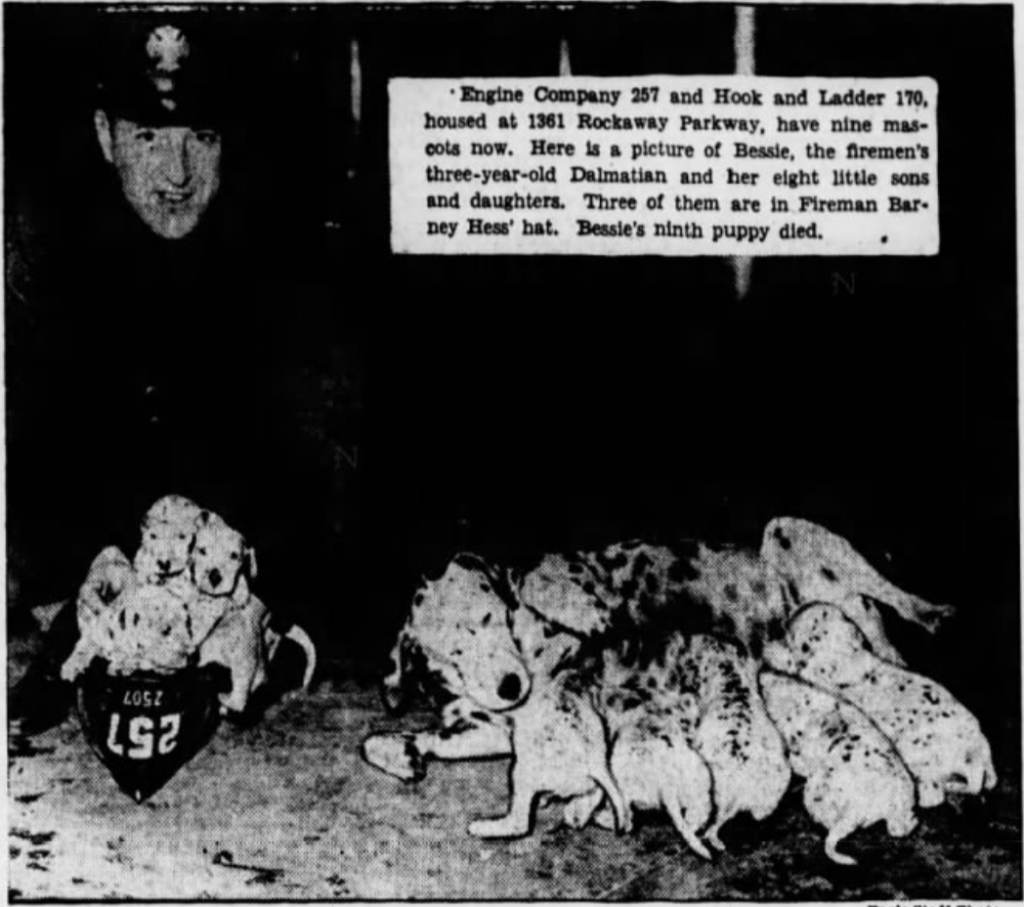

In 1936, a fire buff named C.J. Jones of Cliffside Park, New Jersey, entered the fire station carrying a young Dalmatian puppy. The men named him Cappy and made him a mascot of Engine Company No. 65.

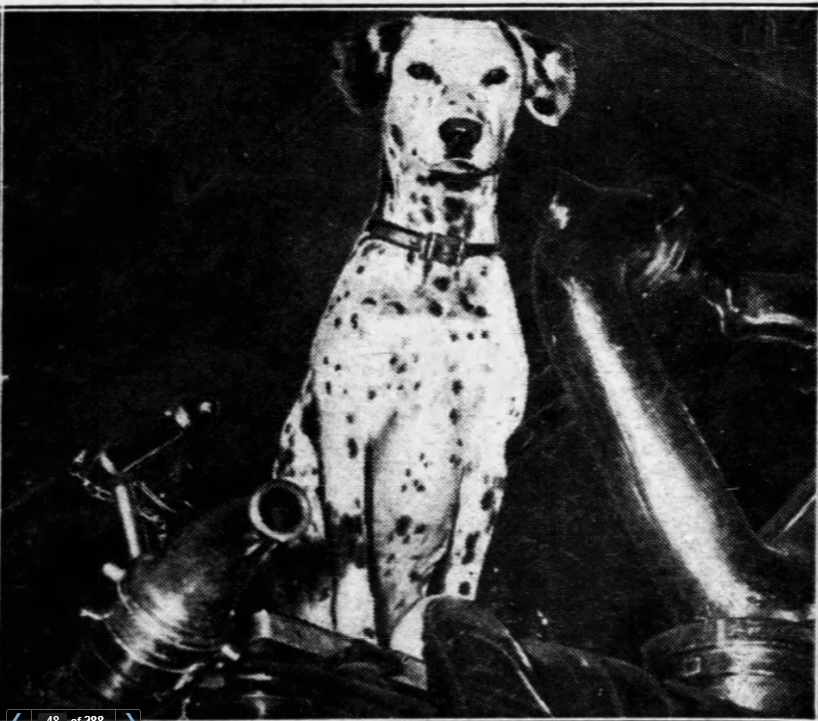

Whenever an alarm sounded for the station, Cappy would jump onto the fire truck—where he “occupied a seat of honor”—and ride to the scene with the fire fighters. He loved the speed, and as he balanced on his perch, he’d lift his muzzle into the wind and treasure every moment of the adventure. Sometimes, when the engine was taking a sharp curve, passersby would gasp because Cappy seemed to be hanging on by only his toenails.

At first, the men allowed Cappy to follow them into burning buildings. In fact, according to several newspapers, he not only carried a cat out of burning building, he actually went to the Ellin Prince Speyer Hospital for Animals to visit her while she was recovering!

Eventually, as Cappy got older, the men had to secure his leash to the seat so he would not join them (the leash also kept him from rolling off the truck as it took sharp curves). As soon as the men returned safely to the truck, he would welcome them back by licking their hands.

When he wasn’t responding to fire calls, Cappy could often be found waiting patiently each day in front of a Spanish restaurant for his daily handout. He had to watch his figure, though, because Cappy was an advertising star.

You see, Engine Company No. 65 just happened to be near the city’s advertising district. Since Cappy was so handsome and photogenic, the firemen offered his services as a model for national magazines.

“He could sell anything,” Captain Edmund Brennan told a reporter. “Illustrators hired him at $5 a day and he was worth it. He could sell anything from an auto to a polio fund subscription.” The men kept a special bank account for Cappy’s earnings, which they used for his food and occasional veterinary bills.

In March 1939, Cappy reportedly went missing after leaving the firehouse for his daily constitutional trip around the neighborhood at 8 am. He was last seen about thirty minutes later ambling northward, having just inspected some subway construction at Sixth Avenue and Forty-eighth Street.

Mrs. George Bethune Adams, resident director of the Ellin Speyer Hospital for Animals, posted a generous reward for his safe return. He eventually returned home, but my theory is that he was at the animal hospital at this time, visiting the cat he had saved from the burning building.

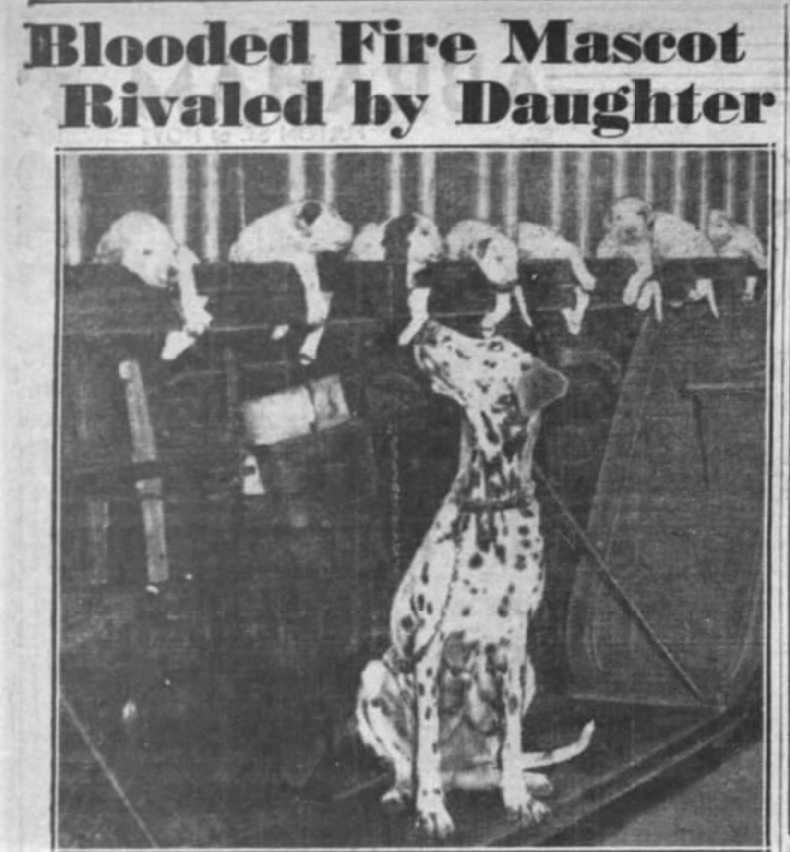

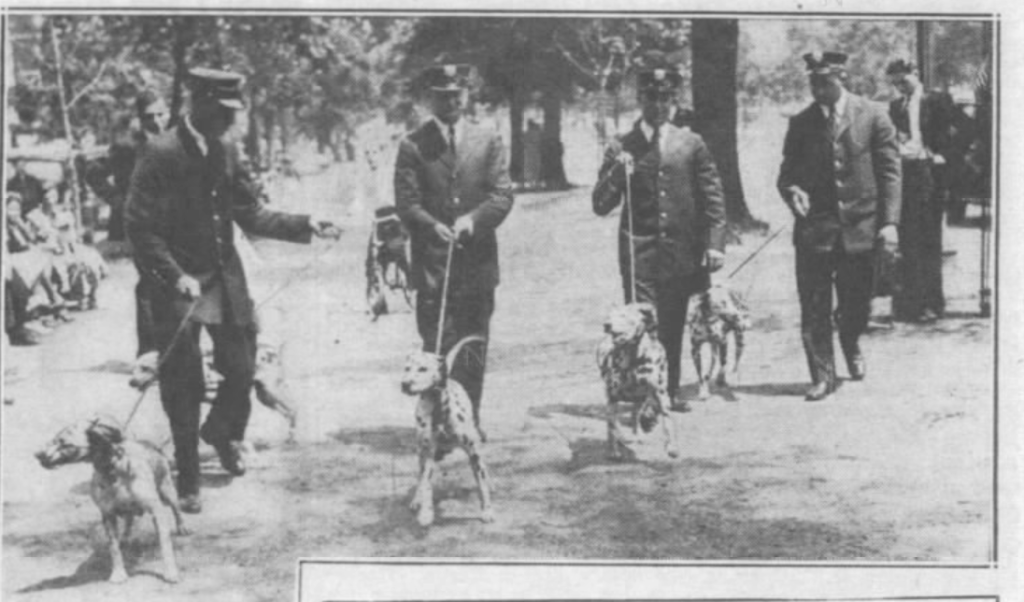

In 1941, Cappy and two of his sons—Raffles and Beau—took part in an exhibition of 25 FDNY Dalmatians at the Westminster Kennel Club’s 65th annual dog show at Madison Square Garden. Although the press surmised that Cappy would do well based on his experience with posing for advertisements, it was King, belonging to Fireman George F. Donnelly of Hook and Ladder 311 in Queens, who was crowned the top pooch of the FDNY.

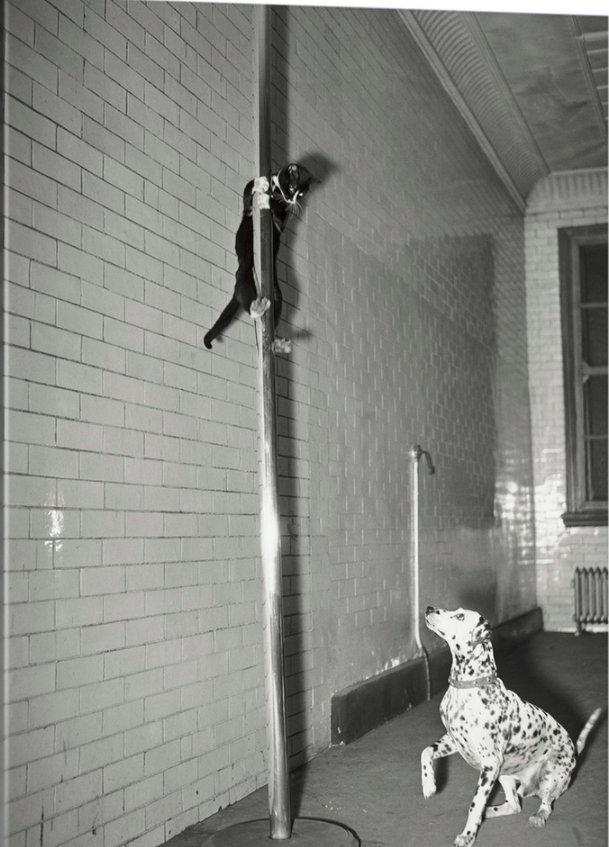

During this time, Engine Company No. 65 had another mascot cat named Henry. Like Peter, the pole-sliding cat of Bushwick, Brooklyn, Henry would slide down the pole with the firefighters whenever an alarm came in for the station. In 1941, a photographer captured Henry sliding down the pole and Cappy watched from below. The photo was published in numerous newspapers across the nation and now adorns my office wall.

Poor Henry disappeared in 1942, which was the same year Cappy took his last rides on the fire engine. By then the modern equipment was so fast it was difficult for him to keep his balance when the equipment took a corner, especially with his aging paws. So, he remained back at the station house where his bed was near the warm chimney. He reportedly brooded over his retirement and whimpered when the trucks rolled out until he finally dozed off into a fitful sleep.

In April 1950, Cappy began to shake and drink excessive amounts of water. The firemen took him to the Ellin Prince Speyer Hospital for Animals, where he was diagnosed with uremic poisoning.

The following Thursday a funeral was held at Bide-a-Wee animal cemetery in Wantaugh, Long Island. Brennan, Francis Hickey, and Eugene Uhl were the only ones who could attend the ceremony, “but they brought with them the grief of all 31 desolate men in New York who couldn’t attend.”

A fund was initiated to purchase a grave marker for Cappy. The monument was topped with a marble fireman’s hat inscribed with the number 65. Brennan told the reporter, “We’ll be out every so often to say ‘Hello’ to Cappy. He never forgot us, and we’re not forgetting him.”

Following the funeral, the men hung a photo of Cappy framed in ribbon and topped with a mourning palm outside the firehouse. The legend under the photo read: CAPPY—1936-1950.

On the door to the firehouse, they chalked up a code signal: 5-5-5-5. Our Mascot. 8:30 AM. (5-5-5-5 is the department’s code for a death in its ranks.)

Asked if the company would ever get another dog, Captain Brennan shook his head and replied, “No, I don’t think so. No dog could replace Cappy. Not for Engine Co. 65.”

*Nickie was not the cat’s real name.