Everyone knows that despite its nine lives, curiosity kills the cat. For the sea-faring cats in this story, it was curiosity and a war-time ban on ship whistles that left them stranded on the Chelsea Piers ship terminal during WWI and WWII.

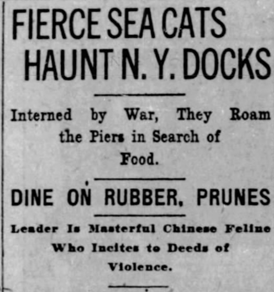

WWI: Fierce Marine Cats Haunt the Chelsea Piers

On January 21, 1917, a New York Times reporter stopped by Pier 58 to interview veteran night watchman Sam Smithers about a reported clowder of cats that had taken over the piers. Cats of all nations had been gathering on the piers since the beginning of World War I, most of them were refugees who had escaped from various steamships that were taking part in the war effort.

The cats prowled in bands of 15 or 20, and were living on bones, dried prunes, and raw rubber (which the sailors said enabled them to spring from pier to pier at night in search of prey). Their wild meows and baleful looks kept many a watchman awake at night.

According to Smithers, the leader of this pack was a large, rough-looking cat with red fur and large yellow eyes with red pupils that glared like port lights at sea. The tom cat was known as Tai-Wan, because he had apparently arrived at Pier 59 by the Jumpsejee Jeegeeboy from Wu-Wu-Wu on the Yangtze.

“Look at them waiting to see where I hide my bit of supper so that one of them can pinch it when my back is turned,” Smithers said as about 20 cats sat watching his every move. The watchman said he regretted saving Tai-Wan’s life with a pole when the feline fell into the water while getting off his ship. “Since then he haunts me at night, and if I have to drop off to have a snooze in the corner, he sticks his claws into my legs or rubs his wiry whiskers against my face.”

WWII: War Ban on Ship’s Horns Strands Cats on Chelsea Piers

During World War II, New York Harbor was the busiest port in the world, with 39 active shipyards and750 of 1,800 existing docks, piers, and wharves classified as active. According to the New York Historical Society, at the height of the war, a ship left the New York Harbor every 15 minutes. The Chelsea Piers (Piers 53 to 62, located between 17th and 22nd streets) served as a major embarkation point for troop carriers that took American servicemen overseas.

It’s important to know that many of these troop carriers, or troopships, were originally passenger liners that were forced out of service and turned over to the Army and Navy. Prior to the war, the passenger ship horns would blast thirty minutes before the gangplank was lowered, 15 minutes later, and then five minutes before the lines were cast off and the ship headed out into the river. These blasts would give stowaway cats that were perhaps checking out the restaurants opposite the piers on 11th Avenue enough time to return to the pier and sneak back on board their ship via the lower gangplank.

During the war, however, the horn blasts were banned, probably so city residents would not confuse them with air-raid sirens. Without the warning blasts, the cats missed their passage. Hence, on March 13, 1942, when another Times reporter visited the piers, about 50 refugee cats had been left to roam the piers, just as their ancestors had done 25 years before.

On this particular day, Lewis J. Gavan (no relation of mine) said he was taking care of a litter of kittens that had been born at the piers. The mother cat, a black and white short-haired cat, had been carried off by a Norwegian sailor who said he was taking her to be a mascot for a ship sailing for the South Seas.

Gavan told the reporter he bought milk for the kittens in the daytime, and at night, Peter Hoey, a roundsman, chopped up chicken liver for them. Hoey also gathered bits of food from the galleys of the freighters for the other hungry cats on the prowl.

Ben Fidd, a retired veteran pier watchman, told the Times reporter that the cats had come from all over the world, including China, Persia, Malta, and Australia. Fidd had some fun with the reporter, and told him that two or three of the cats were from Egypt and meowed in Arabic, and two other felines from Ireland had a Gaelic accent.

Hoey said it was a big job at night keeping the peace between the refugee cats and the freighter mascot cats. Any time one of the marooned cats would sneak on board a freighter, the fighting would start and the fur would fly.

Gavan predicted that by the end of the war, there would be at least 100 cats stranded on Chelsea Piers.

I have a feeling this story does not have a happy ending, so I’ll let the reader come to his or her own conclusion regarding the fate of these seafaring orphan cats.

If you enjoyed this seafaring cat story, you may also enjoy reading about the Christmas feast for Woo-Ki and the Pirate Cats of Chelsea Piers.

[…] World War I and World War II, hundreds of cats from all over the world were left stranded on the Chelsea Piers in New York when the troopships and freighters they had stowed away on left the harbor without them. […]

Having read this I believed it was really enlightening.

I appreciate you sppending some time and energy to put tbis short article together.

I once again find myself spending way too much time botrh reading and posting comments.

But so what, it was still worthwhile!

[…] Manager W.J. Reilly arrived on the scene, he asked the sailors what they were doing with all of the seafaring cats, as they were not allowed to have so many pets on the ship at the company’s expense. He knew that […]