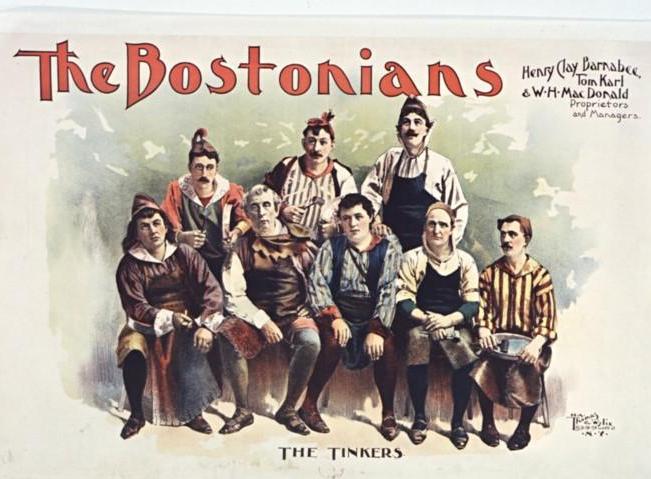

On September 8, 1902, the operetta “Robin Hood” opened at New York’s Academy of Music. The opera was produced by The Bostonians, a touring theater troupe that performed operettas written by America’s foremost composers.

“Robin Hood” was the first successful operetta written by Americans—librettist Harry B. Smith and composer Reginald De Koven.

On the third night of the show, W.H. MacDonald, who was playing the part of Little John, was spooked by what he thought was a ghost horse.

According to news reports, MacDonald was getting prepared in his dressing room when he saw a horse’s head in the mirror. MacDonald was startled at first, and wondered whether the Academy of Music was haunted by a ghost horse or if he was simply going insane.

MacDonald closed his eyes and looked again. Yep, he still saw a horse in the mirror. Maybe, he thought, the Academy of Music was in fact haunted.

A Brief History of the Academy of Music

The Academy of Music was constructed in 1854 at 125 East 14th Street, on the corner of Irving Place. Construction costs of close to $400,000 were funded by a corporation headed by Moses H. Grinnell, a former New York congressman who sold one-thousand-dollar shares to wealthy New Yorkers living near Union Square who wanted a nearby venue for the grand opera.

One of those wealthy residents was James Phalen, who had earned his fortune in real estate. Phalen owned the land on which the Academy was built, and thus, assumed the position of president on the Academy’s board of directors. Phalen and the other stockholders had very lavish privileges–including exclusive possession of a large number of the best seats—which caused numerous rifts between the board and the management.

Designed by architect Alexander Saeltzer in the German Rundbogenstil design, the Academy of Music was lavishly embellished and grand in size, with five seating levels, numerous private and stage boxes, and about 4,000 seats upholstered in crimson velvet. The interior was white and gold and illuminated by thousands of gaslights.

The Academy of Music opened its doors on October 2, 1854, with the performance of Vincenzo Bellini’s “Norma.” For the next 12 years, it was the center of musical and social life in New York.

Then tragedy struck on May 21, 1866.

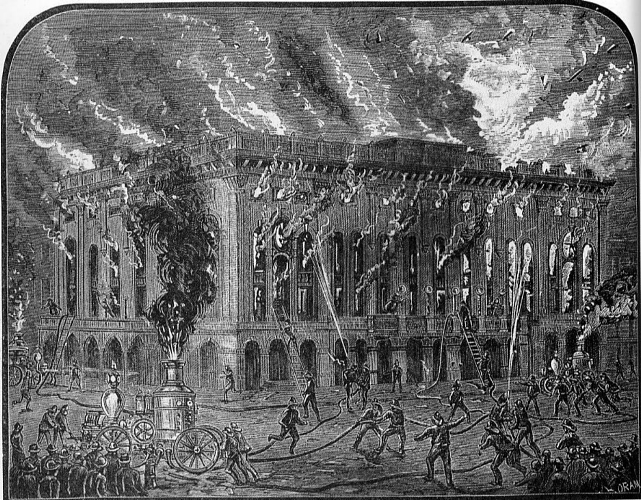

DISASTROUS CONFLAGRATION; The Academy of Music and College of Surgeons Destroyed. Several Other Buildings Partially Burned. Two Firemen Killed and One Very Badly Injured.

—The New York Times, May 22, 1866

Following the devastating fire–which I’ll detail at the end of this story for those who, like me, are interested in firefighting and the history of the Fire Department–plans were made to immediately rebuild the Academy of Music on the same site. It was in this new building that actor MacDonald was spooked by the ghost horse—

According to the story, MacDonald tried to get his wits together and make a run for it, but he collided with an actual horse. What was a horse doing in his dressing room? MacDonald wondered while yelling for help.

Within minutes, the door keeper and two policemen arrived on the scene. The policemen said they had seen the horse galloping down 14th Street, and, thinking it had escaped from its stable, started running after it.

They followed as the horse disappeared into the side entrance of the Academy of Music, and watched as it trotted across the stage toward MacDonald’s dressing room.

The doorkeeper said he remembered the horse as one that had been used in the previous spring’s performance of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

One of the members of the company, who had formerly occupied MacDonald’s dressing room, had a habit of feeding sugar to the horse. The horse meant no harm — he had simply returned to the Academy to get a sugar treat from the new occupant.

The Final Demise of the Academy

When the Metropolitan Opera House was built in 1883, the Academy of Music couldn’t compete, and so it began to offer vaudeville; the venue was also rented by labor organizations in the early 1900s for stage rallies.

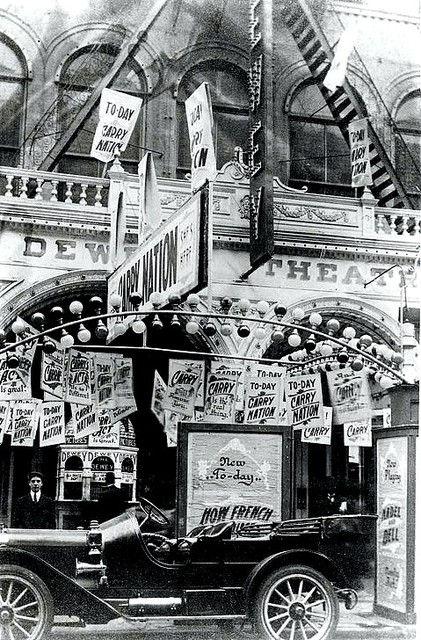

In 1910, movie mogul William Fox, founder of the Fox Film Corporation, took over the Academy’s lease. Fox presented stage plays with a resident stock company and then switched to vaudeville and later films when feature-length movies became the vogue.

On August 21, 1925, the Academy of Music was sold by the Gilmore and Tompkins estates to the Consolidated Edison Gas Company. The original Academy of Music closed forever with a gala “farewell” performance on May 17, 1926. Later that year, the Academy and several other buildings were demolished to make way for Consolidated Edison’s skyscraper.

In 1926, Fox built a new mammoth theater on the former site of the Dewey Theater, the Theatre Unique, and several other buildings between 126 and 138 East 14th Street. He named the new 3,600-seat theater in honor of the demolished grand opera hall.

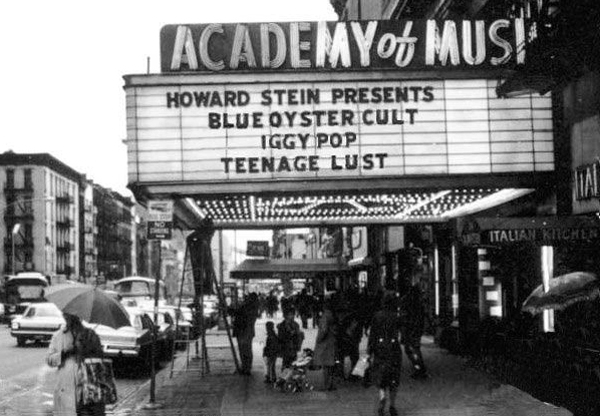

The new Academy of Music, designed by Thomas W. Lamb, operated for decades as an increasingly shabby movie house until 1964, when the venue began showing rock acts at night, while still showing movies during the day.

It was all downhill from there (or uphill if you prefer progress over history):

• 1976: Renamed the Palladium

• 1985: Turned into a multi-level disco

• Demolished in 1997

• Rebuilt as a 12-story residence hall for NYU in 2001; Trader Joe’s moved into the main level in 2006

The Great Fire of 1866

On the evening of May 21, 1866, an Italian opera company hired by Academy manager J. Grau to perform Fromental Halevy’s “La Juive.” This was to be their last performance at the Academy of Music; ballet promoters Henry C. Jarrett and Harry Palmer had just brought in a Parisian ballet troupe, which was scheduled to begin production of “La biche au Bois.”

Just before midnight, shortly after the audience had departed and the artistes had left their dressing rooms, Emil Ruhlman, the janitor, and a gasman discovered wisps of smoke coming from under the left side of the parquette as they were making the evening rounds. A huge volume of smoke drove them out of the building, and upon exiting, they saw flames in the windows on 14th Street.

Emil rushed back inside to save his family, who lived in the building. He was able to get everyone out safely, including his wife, two children, and his 89-year-old mother.

One of the first arriving fire companies was Metropolitan Steam Engine Company No. 5, which was stationed at 186 East 14th Street and had been alerted to the fire by Officer O’Brien of the 17th Precinct.

The company was led by Foreman David B. Waters and Assistant Foreman P. McKeever, and was manned by Engineer W. Hamilton, Stoker C.H. Riley, Driver Alonzo Smith, and Privates (firemen) J.F. Butler, P.H. Walsh, J. Corley, Michael Stapleton, F. Rielley, P.J. Burns, and W.H. Farrell.

Metropolitan Hook and Ladder Company No. 3, led by Foreman James Timmoney and stationed just around the block at 78 East 13th Street, also arrived within minutes of the first alarm.

When firefighters arrived, they could see smoke coming from the upper windows under the roof. They also noticed that the gas used for lighting the theater had not been extinguished. Numerous companies responded to the three-alarm blaze, including Engine Companies 3, 13, 14, and 16, and a few companies from the Brooklyn Fire Department.

Even Engine Company No. 36 of Harlem came down to help out—these men worked for more than two hours protecting Horatio Worcester’s piano factory at 117-121 Third Avenue. The men didn’t know it at the time, but the three-alarm blaze would go down in history as the first true test of the newly created paid fire department.

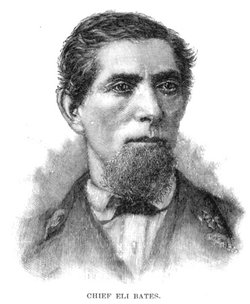

By 12:30 a.m. the flames had gained such headway that, according to The New York Times, “all of the windows of Academy fronting on Fourteenth Street vomited great tongues of living fire…” The smoke was so dense and suffocating that District Engineer Eli Bates gave the order for all firemen inside to leave. His orders came just in time for all but two of the men: Half an hour later, the entire roof had collapsed “beneath the force of the devouring element.”

As the fire intensified, Chief Engineer Elisha B. Kingsland shifted all of the firefighting resources from the Academy to adjoining buildings. Sparks from the inferno ignited numerous structures along the entire block from Irving Place to Third Avenue between 14th and 15th Street, and many buildings were damaged by smoke and water:

• The College of Physicians and Surgeons, 107 East 14th Street

• Grace Chapel, 132 East 14th Street

• The Dutch Reformed Church

• The St. James English Evangelical Church, 107 East 15th Street

• The Hippotheatron

• Col. James L. Frazer’s restaurant

• The residence of Mrs. Gleeson

• Ihne & Son’s 4-story piano factory, 109 East 14th Street

• Irving Hall

• The Arsenal bar room and Mrs. Romaine’s boarding house at 6 Irving Place

Third Avenue:

• No. 122, occupied by James Hundt (pork butcher)

• No. 122 ½, occupied by Charles Kreitz (a beer saloon)

• No. 124, occupied by Edward Holmes (butcher), and the McKerma, Luckenback, and Glynn families

• Rear of 124, occupied by Brander Robertson, Michael Dalton, Mrs. Fogarty, Mrs. Kennedy, and Mrs. Mack

• No. 124 1/2, occupied by J.H. Green (upholsterer), James Boyle, and Mr. Burns

• No. 126, occupied by Seaman Jones (wall paper and paint store), Mrs. Rooney

• No. 129, occupied by Mr. Mish (clothing store)

Lives Lost

When firefighters first arrived on the scene, the fire appeared to be fierce, but not spectacular. While the steam engines were working up enough pressure to start getting water on the building—this took about 10 minutes–Foreman James Timmoney of Ladder Company No. 3 entered the building and spotted flames shooting up from the basement near the stage.

John Dennin and Hugh Kitson of Engine Company No. 13 took a hose inside and were working the pipe, or nozzle, when they were relieved by Foreman Waters and firemen Walsh and Stapleton, all of Engine Company No. 5. Walsh, only 23 years old, was a rookie and had no volunteer experience, but Waters, 26, had been a volunteer for several years before quitting his job as an engraver to join the paid department.

Meanwhile, as other firemen and theater staff were hauling out furniture and other property, the gas that had been accumulating in the theater exploded, turning the building into an inferno. Kitson and Dennin were knocked down by the blast and burned; Kitson got out, but Dennin became trapped between the flames and the front entrance. He was severely burned but managed to escape by leaping through the flames.

Unfortunately, there was no escape for Waters and Walsh. The bodies of the two men were not discovered until 10 a.m., after hours of frantic searching. A team of firemen from Engine Company No. 5 and No. 3 Truck found Waters near the center of the stage. His arms and legs had burned away, but he was identified by a knife and a key in his pockets.

Walsh’s remains were found near the 15th Street side of the stage, just a few feet from the wall that separated the theater from the dressing rooms. His upper torso had burned, and only his trunk could be recovered.

Both men were single; Waters lived with his parents on the corner of 10th Street and First Avenue and Walsh lived with his mother at 82 7th Street. Their families each received $1,000 in insurance from the fire department. Dennin, who was badly burned, received $5 a week while on disability.

Horses Were Saved

Directly across the street from the Academy of Music was a large entertainment venue called the Hippotheatron, a domed building that opened in 1864 and was home to L.B. Lent’s New York Circus. This building was in imminent danger during the fire, and firefighters worked hard to prevent sparks from igniting the building.

While the firemen directed streams of water on the structure, the employees of the Hippotheatron worked quickly to get all of the trained horses, performing ponies, and mules out of the building. The horses were led to Union Square, where they remained until it was determined the Hippotheatron was out of danger.

Unfortunately the animals would not be so lucky the next time fire struck, but that’s another story for a future post.

[…] that date, seven graduates were performing in Uncle Tom’s Cabin at the Academy of Music in New York. These horses were all trained to dash onto the stage and then immediately slow up to […]

[…] was the pet of Jerome H. Sykes, a comic actor and opera singer. Sykes, who rose to fame with the Bostonians, was best known for his portrayal of Constable Foxy Quiller, a bumbling, overweight detective who […]