“Horses galloping from nowhere to nowhere on sliding platforms in front of a quickly rolling panorama; Ben-Hur on the stage is panoramic, pictorial, musical, terpsichorean, religious.” — Edward A. Dithmar, The New York Times, Dec. 3, 1899.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, when the use of live horses and other animals in grand productions on the big stage was all the rage, a thespian college for quadruped actors was just what the doctors ordered. Drs. Martin J. Potter and Samuel S. Field, to be specific.

Dr. Martin Potter, better known as Doc Potter, was a veterinary surgeon and renowned animal trainer who supplied animals to practically all the theatrical companies in America. Able to procure almost any kind of trained animal for a dramatic production, he was known as the “Noah of the Theater.”

Martin began collecting fine horses as a teenager, and over the years his collection expanded to include camels, lions, elephants, tigers, dogs, and scores of smaller animals. At one point he owned more than 50,000 horses and 10,000 other varieties of animals, many of which lived in the stalls, cages, lakes, and fields at his stock farm in Stamford, Connecticut.

Dr. S.S. Field was also a veterinary surgeon and horse trainer who owned a stock farm at his estate on Fulton Avenue in Hempstead, Long Island. Although he was born on a farm in Amsterdam, New York, Samuel didn’t like farming, so he worked making springs for wagon wheels.

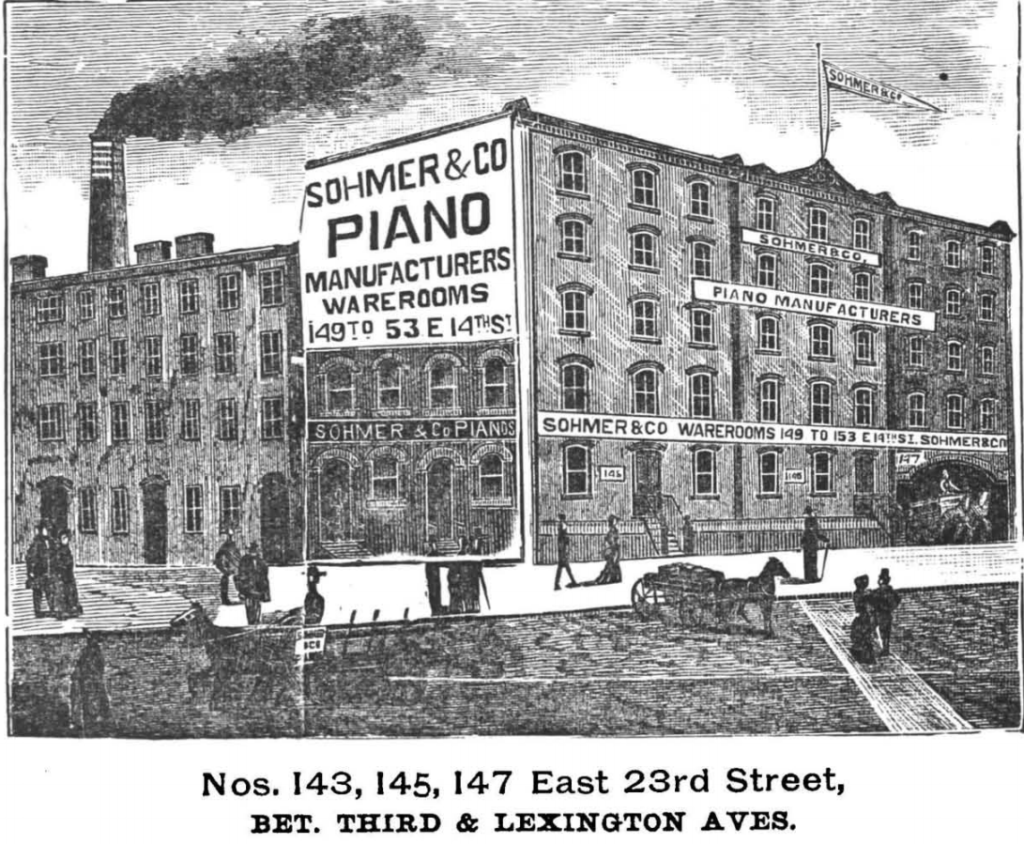

He entered the animal business later in life, after serving in the Civil War and spending a few years as a keeper at Clinton Prison in Dannemora, New York (then considered America’s most brutal, repressive prison institution). Sometime during the 1870s, Samuel took up veterinary practice and opened an office at 29 Lexington Avenue near 23rd Street.

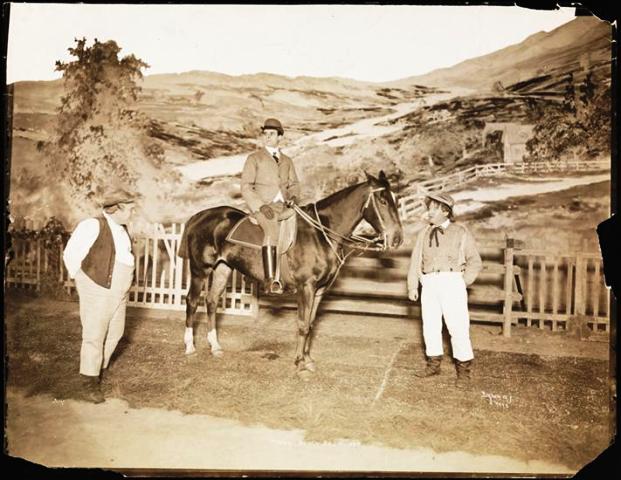

One day in 1887 a friend reportedly asked Martin if he could provide a trained horse for the stage. This request inspired Martin and Samuel to start a business training and supplying animals for theater productions. The pair opened their “horse college” in a large, five-story brick livery stable at 141 East 23rd Street sometime around 1900. The press called it “The Quadrupedal Academy of the Drama.”

On March 17, 1901, a reporter from the New York Morning Telegraph visited the stables to check on the equine undergraduates, as well as a number of graduates actively involved in metropolitan theater engagements.

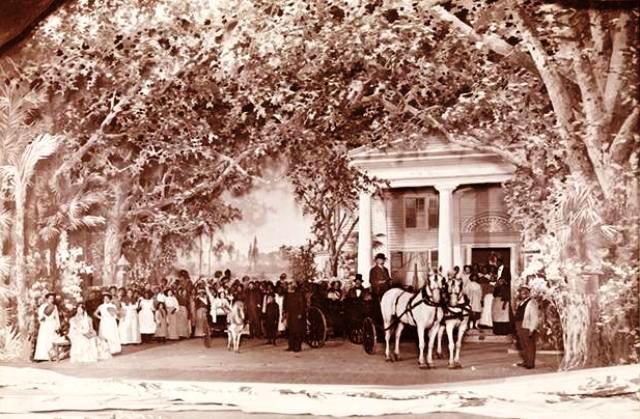

On that date, seven graduates were performing in Uncle Tom’s Cabin at the Academy of Music in New York. These horses were all trained to dash onto the stage and then immediately slow up to allow for the dialogue. The swift galloping entrance gave the audience the impression that the horses had traveled long and hard.

Some of the other horses trained at the equine college included Norma, who performed in Way Down East and Teddy, Tim, Andrew, Joe, and Dutch, who were touring with Hearts Are Trumps. The academy also supplied 237 horses for the production of Joan of Arc as well as numerous trained goats and camels (and sometimes elephants) for other dramatic performances. More often than not, the animals had an opportunity to train with their human counterparts at the stables prior to the actual stage performance.

The Equine Stars of Ben-Hur

One of the most difficult theater productions for the horses was Ben-Hur, which opened at New York City’s Broadway Theater on November 29, 1899. Based on the best-selling 19th-century novel by Lew Wallace, Ben-Hur featured 120,000 square feet of scenery, a live camel trained by Doc Potter (and two fake ones), and what the writer William W. Ellsworth called ”one of the greatest stage contrivances of our day” — a chariot race complete with a rolling panorama of a Roman stadium to simulate Ben-Hur’s victory over Messala.

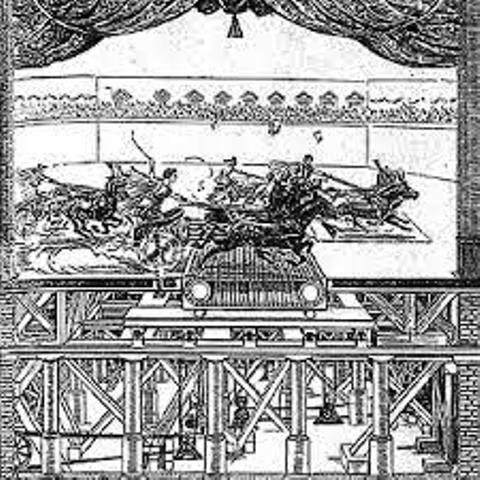

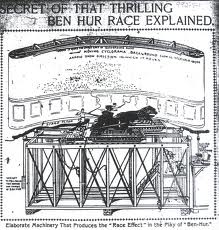

The thrilling scene featured four chariots, each drawn by four live horses and hooked up to an electric motor built into the bed that turned the wheels while the horses ran on a treadmill. The arrangement for each chariot was built into a separate platform that could be moved individually across the stage so that the chariots might alternate the lead in the race.

According to Bernard Hewitt’s “Theater U.S.A.: 1668 to 1957,” the way it worked was that each of the horses was led onto a separate treadmill activated by the animal’s running. Equipped with whips and racing skirts, the actors playing Ben-Hur and Messala climbed into actual chariots and the horses began running behind a darkened scrim.

When the sound built to a fever pitch, the scrim flew up, exposing a chariot race in full stride. As the panoramas rolled, Messala’s treadmills were slowly shifted upstage so that the Ben-Hur chariot would appear to be gaining. In the finale, the wheels were pulled off Messala’s chariot, the horses reared, and the lights fell.

Not only did the horses seem to hurdle toward the spectators, but a continuous panoramic backcloth was wound around upright rollers so that it could be made to travel rapidly in the opposite direction to the horses, and thus, create an illusion of moving scenery. Even the dust was reproduced by a narrow slot in the stage under each chariot wheel — as the wheels span, the dust was flung out behind the chariots.

The mega-hit ran for 6,000 performances over 21 years, and was estimated to have been seen by more than 20 million people. Almost as soon as the curtain fell on the final stage performance in the spring of 1921, a cinematic production from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer was in the works.

Billed as “the triumphant return of Ben-Hur in sound,” the silent film premiered in 1925 and featured synchronized sound effects and live music. In 1959, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer released the feature-length film starring Charlton Heston as Ben-Hur.

The Broadway Theatre and old Cosmopolitan Hall

Constructed in 1887, the Broadway Theatre at 41st Street was the first major playhouse built in what has become today’s Times Square Theater District. Its first proprietors were James A. Bailey (yes, the circus Bailey), T. Henry French, and Frank W. Sanger. The first production was Sardou’s La Tosca, which opened on March 3, 1888.

The building was formerly the old Cosmopolitan Hall, which was erected for use as a great concert hall by the Metropolitan Concert Hall Company and opened on May 26, 1890. The Metropolitan Concert Hall was renamed the Metropolitan Casino by Henry E. Abbey and Edward G. Gilmore, to showcase light opera, but theatrical managers called it The Morgue.

In 1882, J. Fred Zimmerman reopened it as the Metropolitan Alcazar, but that also failed. Next came S.M. Hickey, who called it Cosmopolitan Theatre and soon thereafter walked away. Captain Samuels of Brooklyn converted it into a skating rink during the roller-skating craze, and later it was used for fairs, flower shows, lectures, and billiards.

The Broadway Theatre was three stories with a roof of colored glass, which could be opened for ventilation. About the framework of the roof was a garden, where people could sit and listen to music coming from the stage below in summer.

According to building plans published in The New York Times, the theater was to be as fireproof as possible, and it had electric knobs that, when pushed, would open every single stage door outward so people could get out quickly. There were three stores on the Broadway side of the building, and the two upper stories above the stores had offices. The stage was 44 x 100 feet and had seating for about 2,000 people.

A Tragic Death

By 1906, it appears that the two vets had gone their separate ways. Doc Potter got a job as the vet for the Hippodrome Theatre shortly after it opened in 1905; he was also hired as the veterinarian for the Fox Film Corporation at 130 West 46th Street. In addition to these jobs, he continued collecting and selling animals for stage and screen.

At some point prior to December 1920, Doc Potter had moved his Ben-Hur Stables to 156 East 30th Street, where he ran an animal pawn shop for hard-luck circus men and animal trainers who needed loans. The animals were used as collateral, for which Doc Potter charged “room and board” in lieu of interest payments on the loans.

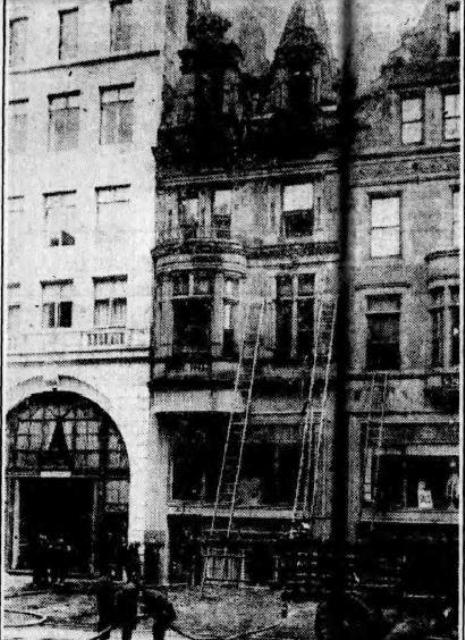

Tragically, in the early morning hours of December 2, 1920, a fire broke out at his home at 27-29 West 57th Street. Five residents, including Doc Potter, were trapped in the buildings and burned to death.

The residents’ deaths could probably have been prevented had the joined buildings not undergone extensive renovations a year earlier, in which the staircases were removed between the first and second floor of each building to create – ironically– more living space.

Four years later, the site of Doc Potter’s death was occupied by the 13-story Chickering building, which you may recall from my last post about a high-flying peacock.

Dr. Field lived a much longer life, and in fact, was named Hempstead’s oldest male resident on his 90th birthday on September 13, 1933.

He had sold his farm in 1907 — it was cut into lots by developers — and he was living alone at 22 Columbia Street in the village by this time (his wife, Margaret, passed away in 1915). Dr. Field passed away on October 28, 1936.

[…] 1901: The Thespian Horse College at Ben-Hur Stables in Gramercy Park […]

[…] 1800s and early 1900s, it was fairly common for theatrical performances to feature live animals. Specially trained horses, camels, and donkeys appeared in many plays on the big stages of old New York, as did several birds […]