Today, we have ticker-tape parades to honor our favorite sports teams when they win the World Series or the Super Bowl. In 1915, New Yorkers had a welcoming parade to honor a chicken. A white single-comb leghorn hen named Lady Eglantine, to be exact.

Mind you, this was not an ordinary hen. This was Addison A. Christian’s $100,000 hen, aka, “The Wonder of the 20th Century.”

This was the hen that laid 314 eggs in 365 days as part of an egg-laying competition at the Delaware Agricultural Experiment Station – no ordinary feat, considering the average hen at the time laid about 70 eggs a year.

Lady Eglantine was hatched on April 15, 1914, at Eglantine Farms in Greensboro, Maryland. She was the chick prodigy of the son of a 218-egg hen, who was mated with a 260-egg hen. Her eggs sold for up to $50 each, which was a fairly good price, considering the good odds of her offspring being good egg layers.

The champion hen was a small bird, only 14 inches high and just under 4 pounds. But unlike normal hens, which took about 100 days off from the job to rest and molt, Lady Eglantine was a team player and took only 51 days. Perhaps her special diet of whole and cracked grains, ground grain mash, beef, oyster shells, grit, charcoal, and greens provided the extra stamina.

Lady Eglantine and Her Flock Come to New York

In December 1915, Lady Eglantine appeared at the eighth annual show of the Empire Poultry Association, which was taking place in conjunction with the Empire Cat Club and Empire Cage-Bird Association shows at Grand Central Plaza in New York. (I wonder who thought it was a good idea to show cats and birds in the same place at the same time?)

The night before the show began, Mr. Christian treated his prize hen to a going-away party at the Hotel Walton in Philadelphia. He then traveled with her and her entourage (reportedly 21 various and sundry men, including some security guards and her very own “chef”) in their own special sleeper Pullman parlor car to New York’s Pennsylvania Station.

Upon their arrival at Pennsylvania Station that morning, there was a large crowd waiting for Lady Gaga (oops, I mean Lady Eglantine) in the waiting room, including poultry fanciers, Mr. Willard D. Rockefeller of the Hotel Imperial, and her New York press agent, Cromwell Childe. Mayor John Purroy Mitchel, who was recovering from a recent operation, sent his regrets.

During this welcome reception, some of the men in her traveling party blew bugles and worked to protect Lady Eglantine from everyone’s clutches. Apparently one of the hen’s feathers dropped to the floor during the commotion (she was finally taking a break for molting), and the crowd made a mad rush it. A man grabbed it and tucked the valuable memento into his hat.

From Pennsylvania Station, Lady Eglantine was driven to the Hotel Imperial, just one block away on Broadway. She rode in a fancy car belonging to vaudeville actress Kitty Gordon, which was followed by a second car for the welcoming committee as well as a sightseeing bus for the men who traveled with her from Philadelphia. A few “moving picture operators” filmed the small parade from the railroad station to the hotel.

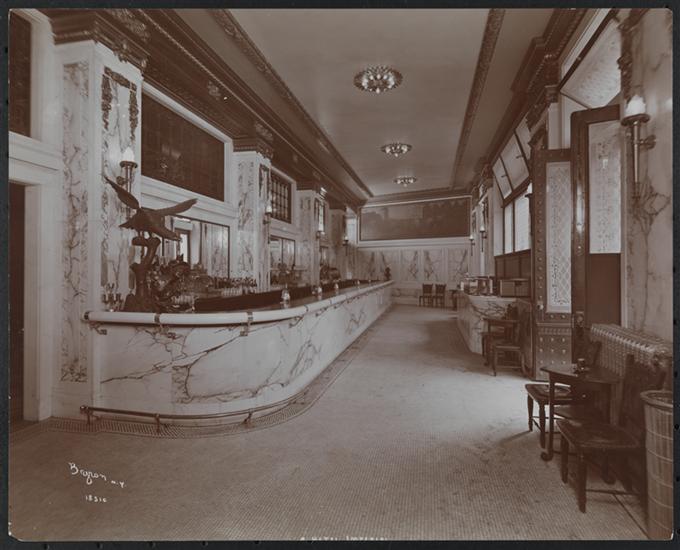

The whole flock arrived at the Hotel Imperial at 11 a.m., where they were greeted by a large sign in the lobby that read: Welcome Lady Eglantine, the Wonder of the 20th Century. 314 Eggs in 365 Days, the World’s Record.

Mr. Rockefeller, the head manager of the Imperial Hotel (no relation to the Rockefellers) attached a pen to one of her claws and had her “sign” the register. She also posed for photos with Miss Gordon, who was appearing in “A World of Pleasure” at the Winter Garden and apparently looking for some extra publicity. (Miss Gordon insisted that this was not the case; she said she grew up on a farm and just loved chickens.)

After taking a brief rest in the “Imperial Suite” (where she was to spend each night), Lady Eglantine was transferred to the Grand Central Palace in a flag-bedecked automobile with, as The New York Times reported, “more factitious fuss than is customarily accorded the prima donna of a royal opera company traveling in state.” At the Palace, she was placed in a pen in a position of honor on the mezzanine floor, surrounded by a dozen of her brothers and sisters in another coop.

Rumors quickly spread that her champion eggs were worth $50 a piece, to which one attendant remarked, “That’s more than they charge for a soft-boiled one at the Ritz-Carlton, so there ain’t no such thing.” Some people were willing, though, to pay up to $100 for a clutch of eggs, while others paid $50 for each of her siblings.

As the Syracuse Herald noted: “New York, like every other large city, wants plenty of fresh eggs for breakfast, at a reasonable price, and since a hen that lays 314 eggs in a year is a mighty step in that direction, New York has taken Lady Eglantine into its arms.

Lady Eglantine and her entourage returned to Maryland on December 11 in an ordinary freight car. According to news reports, her egg-laying was going to be put on hold, as she was scheduled to appear in several other poultry shows across the country.

On Valentine’s Day 1916, Lady Eglantine was married to a rooster “of the highest lineage,” whose mother also had a record of 272 eggs in one year. The Washington Post reported that Lady Eglantine was presented a diamond studded gold anklet from the Philadelphia Poultry Association, which they used as the wedding ring at the marriage ceremony.

I’m not sure if all the previous egg-laying finally got to her, or if it was too much excitement for such a small hen, but poor Lady Eglantine did not live much longer after she wed. She passed in September 1916, as reported in The New York Times and other newspapers. An autopsy report attributed her early death to an enlarged and overworked heart.

According to the Greensboro Historical Society, Mr. Christian took her body to a Philadelphia taxidermist, where was “restored to nearly life-like appearance.” He then gave her a resting place on his library table, which is where she stayed until he died in 1926. It is believed the diamonds were removed from the anklet and set in custom-made rings for Christian’s two daughters.

Lady Eglantine’s stuffed form remained at the Christian house, although she was reportedly relegated to a cardboard box under a desk in the farm office.

Over the years, several of the children who lived at the farm played with her, and a few brought her to school for special projects. Today, she makes her final roost at the museum of the Greensboro Historical Society in Maryland.

Why “infamous McKim, Mead, and White”? Surely the firm that made the Morgan Library and the late Penn Station should be the “glorious for all time McKim, Mead, and White.” Or is the infamous in reference to the whole Harry K. Thaw incident?

Oh, I am embarrassed! Of course I meant “famous” or actually, “renowned” would be a better word — this is what happens when I post stories late at night after putting in long hours at my full-time job. They were in fact glorious, and they were also quite famous, which is what I meant to write. Of course, they were famous for their fabulous buildings and for White’s affair and murder, but either way, I am going to correct this right now.

Thank you, also, for catching this and querying my word usage.