The following cat tale of the Lower East Side is dedicated to my cat Romeow, who passed away after 16 years of life on July 21, 2014.

On June 15, 1904, the General Slocum caught fire and sank in the East River. An estimated 1,021 of the 1,342 people on board the side-wheel passenger boat were killed — most of them German American women and children from the Lower East Side who were all dressed up and on their way to a picnic hosted by St. Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church.

Many of the victims had lived on East 4th Street, including Lina Giessmann, Minnie Cohn, Clara Erhardt, Eugene Hansel, Louisa and Alfred Ansel, Grace Iden, and Mrs. Katy Ambrust and her nine-year-old daughter, Florrie, of 166 East 4th Street.

Five weeks after what was to be the worst maritime disaster in New York City’s history, the residents on East 4th Street had, at least, a little something to celebrate when their favorite cat was rescued after spending two years stuck between two tenement buildings.

A Brief History of the Neighborhood

Before I tell you about this special cat, a little background on this particular section of the Lower East Side is warranted.

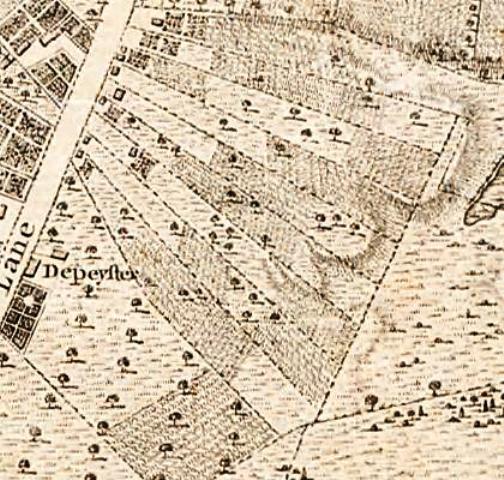

The land that now comprises the Lower East Side was originally part of the Dutch West India Company’s Bowery No. 2, acquired by Petrus Stuyvesant, and Bowery No. 3, granted to Gerrit Hendricksen and later acquired by Phillip Minthorne around 1732. Both these large farms were bordered on the west by the Bowery Lane (today’s Bowery).

Following Phillip Minthorne’s death in 1756, much of the eastern half of the 110-acre bowery was sold to John Jacob Astor. The western half was divided into 27 individual lots, three for each of his nine children: Philip Minthorne, a farmer; John, a cooper; Henry, a tinman; Mangle, a cooper; Hannah, the wife of Viert Banta, a house carpenter; Hilah, the wife of Abraham Cock, a cooper; Margaret, the wife of Nicholas Romaine, a carpenter; Sarah, the wife of Samuel Hallet, a carpenter; and Frankie, the wife of Paulus Banta, also a carpenter.

Each of his heirs received a lot along the Bowery, an internal meadow lot, and a salt-marsh lot closer to the East River. Ownership of most of the Minthorne property was eventually consolidated under Mangle Minthorn, Philip’s most prominent son.

Development in this area of the Lower East Side picked up during the 1830s, with elegant single-family row houses turning once empty land into one of New York’s most prestigious neighborhoods. By the 1850s, many immigrants began to settle in the area as wealthier residents moved farther uptown.

The lovely row houses were converted for multiple-family dwellings and boarding houses, and eventually replaced by tenements in the 1860s to accommodate the housing demand. These buildings were later called “pre-law” tenements because they predated the Tenement House Act of 1879, which required windows to face a source of fresh air and light (as opposed to an interior hallway, as was the case with the older railroad flats).

Had the buildings in the following story been constructed in the dumbbell shape adopted after 1879 by the “Old Law” tenements, our featured feline could have been rescued immediately from the air shaft rather than spending two years in a three-inch wide prison.

A Kitten Takes a Tumble

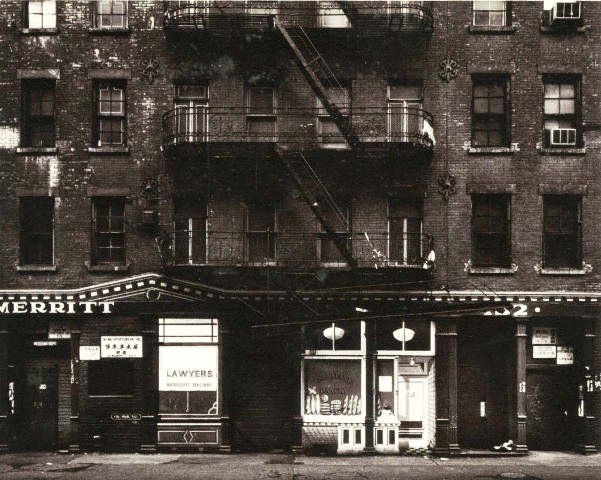

Like many tenements of the Lower East Side, Nos. 163 and 165 East 4th Street were five-story brick buildings with a commercial business and two rear apartments on the ground floor and four three-room flats on each of the upper floors. Only one of the rooms in each apartment had direct window access; the remaining interior rooms had no windows and no ventilation.

These two buildings occupied the same long and narrow footprint (about 25 x 50 feet) as the row houses of the previous decades. Thus, they were constructed extremely close together – perhaps as close as 3 inches toward the ground and 14 inches near their rooftops (the old walls of the buildings reportedly bulged out toward the ground floor).

On September 1, 1902, a striped kitten was living in the top rear apartment at No. 163 with John Poppenlauer, his wife, and family. With the arrival of a new baby boy, John decided to isolate the kitten on the roof to keep it away from the infant.

Whether some mischievous boy pushed it, or it was just curious and clumsy, the poor little kitten fell into the crevice between the rooftops and landed at the bottom of the brick chasm. There was no escape; the crevice was closed off front and back, and even some tin roofing closed off part of the top, giving the kitten very little air and light.

During the early days of imprisonment, the neighbors watched from the roof with pity as the kitten tried to climb up these slippery walls, only to fall back down. The people soon became divided into two factions: those who thought the kitten should be killed and relieved of its misery, and those who believed that while there was life there was hope. George Betz and his wife, who lived on the top floor of No. 165, and Mrs. Rose Kolb, who lived at No. 163, sided with those who believed in miracles.

Although cats were plentiful in this neighborhood, Holey, as she was named, got everyone’s sympathy with her continuous howls and meows. Fishing for the kitten using fish hooks with meat, button hooks, nooses, miniature scaffolds, poles, and other devices became a common diversion for the residents.

Men, women, and children would often sit on the roof and talk to her. Some neighbors, like George Betz and Mrs. Kolb, also lowered buckets of water and food down the shaft, including wienerwurst, chicken and fish. (Food-wise, Holey made out better than any of the other stray cats on the street.)

A Kitten Grows in the Lower East Side

Meanwhile the kitten continued to grow – the people fed her so well, in fact, that she got fat and could only turn around on the wider end of the shaft. George told Gustave Froelich, the owner of No. 163, that he was going to cut a hole in the cellar wall if the cat got any fatter. “Every time I looked down and saw the poor prisoner my heart was touched, and I made up my mind she would not spend another winter down there.”

For two winters, though, Holey survived in the narrow brick prison. Sometime the snow would pile up and no one could see her for days at a time. Although she could keep fairly dry under the end that was covered by the tin gutter, during heavy rain storms the shaft would fill up with a couple of inches of water. George reportedly made a raft for the cat, which he lowered down to her. When it rained, Holey could “sail” on the makeshift raft.

The cat’s predicament finally got the attention of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA). The agent who came to investigate was in favor of killing the cat. First he suggested shooting it, but the cat’s advocates argued that this might jeopardize the safety of the human residents.

He also tried to send down poisoned liver, but the cat had instinctive wisdom and ignored it. As the women of the neighborhood began mobbing him and shouting that he was being cruel to Holey, the agent finally gave up and left.

A Cowboy to the Rescue

Finally, on July 22, 1904, a former cowboy who had learned how to use a lariat in the West came to the rescue with a clothesline noose. At 7 in the morning he went upon the roof of No. 163 and, as Holey sat amazingly still, he got the noose around her and freed her. Although Holey tried to escape, George was able to grab her and bring her to Mrs. Kolb, who had expressed an interest in adopting the cat. Once in the apartment, Holey drank some milk and ran under a bed.

It took Holey a while to adjust to daylight. It also took some time for her to learn to walk in directions other than back and forth along a straight line.

Another Cat Takes a Tumble

Three years after Holey’s rescue, a white cat moved into an apartment at No. 163 East 4th Street. The apartment was home to Louis Leichtman, his wife, and their three children, Aaron, Ruth, and Isaac. Louis named the cat Gittel, which means “good” in Yiddish.

Gittel brought much luck to Louis, and according to a story about the cat in The Sun, he would have done anything for her in return. Apparently so.

On July 21 1908, Gittel was on the rooftop of No. 163 when she fell into an unfinished chimney that ran down to the basement. Louis and his family could hear Gittel howling all night long. The next day, instead of going to work at the National Employment Agency, Louis made a rope ladder of cord and sticks and lowered it down. Of course, the cat would have none of it.

Next, he tried lowering liver skewered to the rope, pails of milk, and bits of fish. That didn’t work, so Louis asked the landlord if he could make a hole in the wall in the basement. The landlord refused.

Desperate to free his beloved Gittel, Louis resorted to lowering his son Aaron down the chimney, but Aaron got stuck halfway down the shaft and some friends and neighbors had to help Louis pull him out.

Finally, four days after Gittel had fallen down the chimney, Louis sought help from the SPCA. Agent Thomas Freel responded and found a plumber in the neighborhood. Together, the men were able to create a hole in the wall. The cat, of course, was too frightened to come out, so Agent Freel went back up on the roof and tossed a few pieces of brick down to encourage the cat to run out the hole.

As Gittel emerged from the hole, all the neighbors shouted in joy.

The Franklin D. Roosevelt Houses

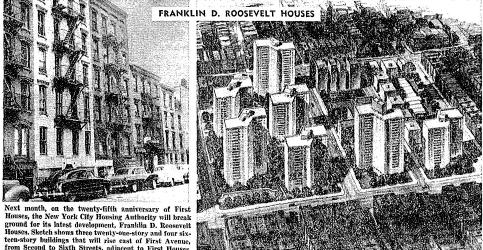

In 1959, 1,738 families and 300 small businesses were evicted from the four-block area bounded by 2nd Street, Avenue A, 6th Street, and 1st Avenue. All of these Lower East Side tenements were demolished over the next two years, including Nos. 163 and 165 East 4th Street.

In December 1960, the New York City Housing Authority broke ground for the Franklin D. Roosevelt Houses, a complex of seven buildings comprising 1,200 apartments. Today, the complex is called Village View.

Interesting history. My Grandfather grew up at 163 East 4th Street.

I’m glad you enjoyed it. I always hope that people will stumble upon a relative or the home of a relative in my stories!