To the Coroner or First Police Officer that Finds My Body Here: I beg of you to telephone to President Roosevelt. He will have my body cremated. I have written to him, have made my will, and all I have is his. He will have everything attended to just as I wish it to be, and all will be right. He knows where to find everything. Please find enclosed $5, and a thousand thanks for your kindness.

Please do not let my poor kittens be frightened or annoyed. President Roosevelt will take them as soon as he receives my letter I mailed to-night to him. Please let them stay here until then. My heart is broken, so I take my own life in the familiar way I know by drinking chloroform. No one is to blame but myself. I trust my spirit and future life to a merciful and loving God, who knows and judges our sorrow. —Lulu B. Grover, December 8, 1906

Lulu B. Grover loved her two Angora cats almost as much as she adored President Theodore Roosevelt. So when she decided to end her life on December 8, 1906, she first made sure that all the necessary preparations were in place to ensure her cats went to a good home after her death – in other words, the White House.

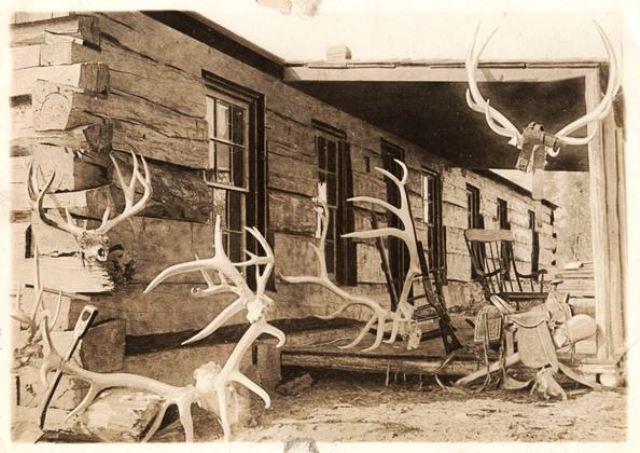

Lulu was reportedly the daughter of a rancher named Smith, who supposedly owned the ranch adjacent to Theodore Roosevelt’s Elkhorn Ranch near Medora, North Dakota. Lulu allegedly married sometime around 1880 when she was 17, but by 18 she was a widow. I say “reportedly” and “supposedly” because when Lulu told stories about her earlier life to her middle-age women friends in East Harlem, she was not quite of sound mind.

Lulu, who was described in the newspapers as a comely woman about 45 years old at the time of her death, often claimed to be a distant relative or good friend of Roosevelt. She loved to tell people how, as a young woman in Medora, she would take long horse rides with Theodore across the North Dakota prairies. She also claimed to have met him in New York on several occasions, including the time she bumped into him at a bookseller’s shop.

Mrs. Grover was also quite fond of the president’s eldest son, Theodore Junior, for whom she purchased several Christmas gifts when Roosevelt was the governor of New York. According to news reports, she sent the boy a shotgun, compass and watch. Roosevelt wrote back to the mysterious gift-giver, “Dear Sir or Madam,” requesting that no more presents be sent to his son as he didn’t want the boy to be spoiled by strangers.

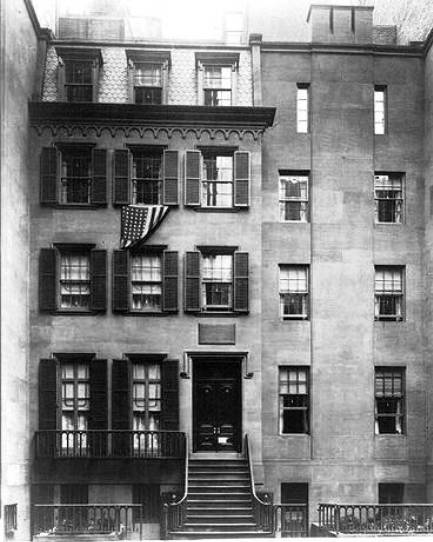

According to Mrs. Marie Hunter, who was caretaker of the house at 2089 Lexington Avenue where Lulu lived, Lulu was a magazine writer and artist who was always well dressed, and seemed to have a generous income from an unknown source. Although she loved to paint and do needlecraft, her chief concerns in life were her two cats, Magistrate Joseph Pool and Queen Fairy Snowdrop. Every day she would have meat cut up into fine pieces for them and she was always concerned about their welfare.

In December 1906, Lulu Grover was renting the parlor floor of the house on Lexington, which comprised two large rooms and a bath. Lulu had found the apartment through Mrs. Hunter, who had previously rented rooms to her in a house at 2 East 119th Street near Fifth Avenue.

It was while she was living on 119th Street that Lulu began calling her cat Magistrate Joseph Pool. According to news reports, in January 1906 Lulu Grover had charged another tenant, Mrs. Emily Wishauser, of throwing water on her whenever she complained of the woman’s dog, which frightened her cat Flossie. Appearing in Harlem Court before Magistrate Pool, Emily said she threw the water in self defense when Lulu came after her with a poker and a revolver. For some reason, Magistrate Pool took Lulu’s side – hence, she named one of her cats in his honor.

On November 23, 1906, Lulu wrote her last will and testament in which she bequeathed her entire estate – including about $800, some jewels, and the two Angora cats — to President Roosevelt. In the will, Lulu noted that Roosevelt was “her only true friend in trouble.” Her neighbors, Edwin and Rosetta Taft, signed the will as her witnesses.

Three weeks after preparing her will, on a Saturday night, Lulu wrote a letter to President Roosevelt. In the letter, she told him he would find her will and a bank book sewed into the lining of the cat basket, and the jewels in a hiding place under the hearth. Then she went into the bathroom and swallowed a vial of chloroform.

Lulu may have gotten the idea to commit suicide by ingesting a chemical poison from a previous neighbor, Adelene L. Callender, who lived in the flat above Lulu at 58 East 84th Street in 1898. At that time, Lulu had accused Police Captain Henry Frers and Policeman Joseph A. Wasserman of the East 88th Street station of hounding her and threatening with her arrest because they said she had a bad character.

She supposedly contacted then Governor-Elect Theodore Roosevelt – who had served as New York City’s Police Commissioner from 1885-1887 — and told him that the constant police harassment had caused her neighbor Adelene, to kill herself by taking carbolic acid. Roosevelt apparently wrote back saying he would have the matter fully investigated.

On Sunday, December 9, Rosetta Taft (a niece of then Secretary of War William Howard Taft) heard groans coming from Lulu’s apartment. She found Lulu lying on the bathroom floor in a house gown and losing consciousness. The place smelled of chloroform and there was an empty vial on the floor. Rosetta called for the police at the East 126th station and for Doctor E.G. Maupin of 151 East 127th Street.

Lying on her hospital bed at Harlem Hospital later that day (many newspapers reported that she “would probably die” there), Lulu was questioned about an incident that took place during the wedding of Theodore’s daughter, Alice, and Representative Nicholas Longworth II. Apparently, a “woman in blue” tried to break into the White House, claiming she was a magazine writer. Lulu denied the charge.

A Shrine to President Roosevelt

As Lulu lay dying in the hospital, Detective Sergeants O’Rourke and Charles J. Kammer searched her rooms. In one room, possible a study, the walls were covered with pictures of the president at almost every stage of his career.

The room also contained many pictures cut from newspapers and magazines, three oil paintings of him that Lulu had painted (one in uniform on horseback, one standing in his Rough Rider’s uniform, and one in civilian clothes), a few poems she had written about him, and several tapestries in his likeness. On the book shelves was a complete collection of his writings.

The detectives also found two letters on standard writing paper — the one to the coroner transcribed above, and another to her neighbors, Mrs. Taft and Mrs. Lyons, in which she spoke of the pleasure she had in knowing them and apologized for any shock she caused them by taking her own life. Finally, the detectives found a cat basket and two Angora cats.

Lulu Grover died at Harlem Hospital on Sunday, December 10 — the very same day Theodore Roosevelt became the first American to win a Nobel Prize. Her body was taken to the undertaking shop of W.P. St. Germain at 1984 Lexington Avenue.

He held the body there for three days waiting for someone to claim it. During this time, all of her property was turned over Public Administrator William M. Hoes. This included a wicker cat basket that was lined with silk inside and out (the bank book and will were located under the inside lining) and several small diamond pieces and other jewels, which were found inside a leather bag tucked into the smoke vent of the fireplace chimney.

Hoes knew that he could sell the jewelry at an auction, but he was in a quandary as to what he should do with the Angora cats. He could not give them away, he told the press, because they had been willed to President Roosevelt. The care of the two cats worried him greatly, in fact, and he appealed to Mrs. Hunter to relieve him of the burden. Mrs. Hunter wrote to President Roosevelt about the cats; he told her to send them on to Washington and he and his family would take care of them.

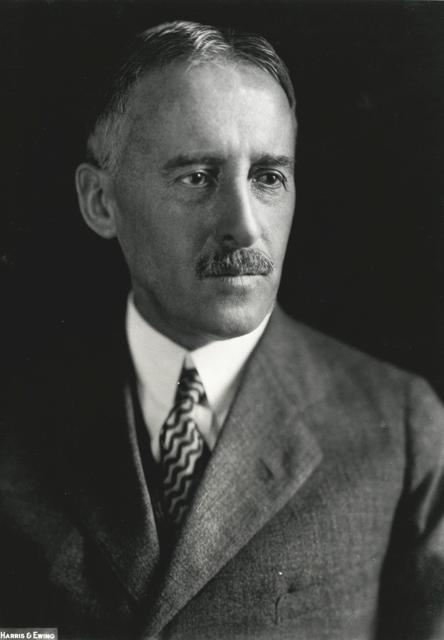

Even though he vehemently denied knowing Lulu, President Roosevelt saw to it that her last wishes were carried out. Under his orders, U.S. District Attorney Henry L. Stimson supervised the cremation of her body in the Bronx and burial of her ashes at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx (the president was adamant that she not be buried in a pauper’s grave).

Only four people — her friend Mrs. Richard H. Connor of 72 East 120th Street, Secret Service Agent Tate, and the undertaker and his daughter — attended the funeral.

Following Roosevelt’s request, Stimson also made arrangements to have the two cats sent to the White House. A carriage arrived at Lulu’s former apartment house on Lexington Avenue, and the two cats reportedly traveled with Douglass Robinson, the president’s brother-in-law, to Washington DC.

At the time, the Roosevelts had several pets at the White House, including a few guinea pigs, dogs, ponies, a cat with six toes, a parrot, and two Kansas jackrabbits. The grounds of the White House were also covered with very tame squirrels – one was even so bold to walk into the White House (guess the Secret Service were not doing their jobs). I’m sure the large house and lawns must have seemed like paradise for two Angora cats who grew up in a small apartment Harlem.

At an auction of Lulu Grover’s estate in September 1907, one of the items was an 18-carat gold ring in which was set two small diamonds and a tooth that the auctioneer said formerly belonged to Teddy Roosevelt.

Robert R. Jordan, who had an antique shop at 762 Lexington Avenue, bought the ring and exhibited it on a royal purple velvet cushion in the shop window. A friend of Lulu’s said Theodore reportedly gave the tooth to Mrs. Grover in North Dakota when she asked him for a keepsake. Robert thought he could get about $25 for the ring.

In June 1907, New York State Attorney General William S. Jackson notified the president that some distant relatives from New York City, Fitchburg, Massachusetts, and Fresno, California, were seeking the estate. There was no further mention of the final outcome of her estate in the newspapers.

One of your best, I think. Again, animals (especially cats it seems) sure got special attention in those days.

Glad you enjoyed it — I think it would make a great addition to a documentary on the Roosevelt family.

…Yeah..? Really.., WHY, are you soo, “..Sure ‘IT’ must have seemed like paradise to two Angora cats who grew up in Harlem”…??? Please do explain, why “IT” must have seemed like “PARADISE” to these two cats who grew up in Harlem… ?? Please elaborate..!!

Consider that these two cats were living in an apartment — some sources say it was 4 rooms, others say it was only 2 rooms — and that their owner was not of sound mind. She supposedly was caring for them, but who knows what their living conditions were really like.

My comment had nothing to do with Harlem or New York City — I love both — but with their home. Imagine being a curious cat and moving from a two-room apartment to the White House, or to any large house for that matter. Think of the possibilities in searching for mice, finding cozy corners to sleep in, chasing mice through a large front yard, just exploring in general. At least to me, that seems like it would be paradise for a cat!

As an aside, when I was in my 20s, I moved into a very large house in the country with my cat, Clypunskins. My roommate, who had been living in a small basement apartment in Brooklyn, also brought her two cats to the new home. One of the first things she said when her cats, Merlin and Wicked, discovered the great outdoors was, “They think they’ve died and gone to heaven.” Her statement was what came to mind as I wrote this story.