Of all the athletes in the world, baseball players are no doubt the most superstitious of them all. Perhaps that’s why the appearance of a black cat at the Polo Grounds created quite a stir…

Dr. Stuart Vyse, an author and psychology professor at Connecticut College, says one reason baseball players are such a suspicious bunch is that the game involves a lot of waiting around. “And if they’re waiting, they have time to perform these rituals.”

In general, superstitious players and coaches will always go out of their way to avoid stepping on the foul line on trips to and from the dugout so as not to jinx their game or their game stats.

These same folks believe that if a black cat crosses their path they’ll have bad luck and bad stuff will happen during the game or series.

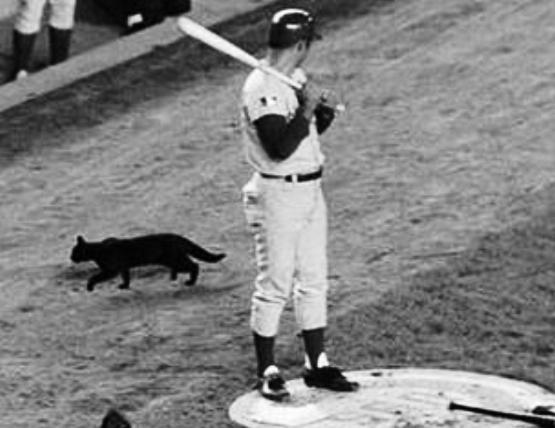

The Black Cat at the Polo Grounds

On September 21, 1932, in a game between what were then the New York Giants and the Boston Braves (today’s San Francisco Giants and Atlanta Braves), superstition struck twice when a little black cat appeared on the field of the Polo Grounds and began meddling with a ball that had just landed on the foul line. For Braves pitcher Tom Zachary, the bad luck signs were enough to shake him up so much it cost him the game (at least that’s what he said).

It was the bottom half of the final inning and the score was tied with Zachary on the mound. Giants slugger Carl Hubbell took a swing, sending the ball down the third-base line.

Just as the ball rolled onto the foul line, a skinny black cat came out from under the left-field stands, made his way across the diamond, and walked up to give the ball a sniff. As the cat started to play with the ball, everyone on the field and in the stands froze in place.

“It’s a black cat!” shouted Al Spohrer, Boston’s catcher, breaking the silence and sending the cat into a panic around the field. As the chaos ensued, Braves shortstop Walter “Rabbit” Maranville threw a handful of dirt over his left shoulder (he didn’t haven’t any salt to ward off the devil).

The players, umpires, and over 54,000 fans in attendance continued to watch in amazement until a groundskeeper finally caught the cat and carried him back to the stands.

Still shaken by the appearance of a black cat on the field, Zachary was not on his game when he pitched the next ball to Hubbell. The Giants’ southpaw singled to left field, and although he was forced out by left-fielder Joseph “Jo-Jo” Moore, Jo-Jo was able to score – he even picked up some of the dirt with the cat’s paw prints as he ran to home plate — and the Giants won the game by a score of 2 to 1.

A Brief History of the Polo Grounds

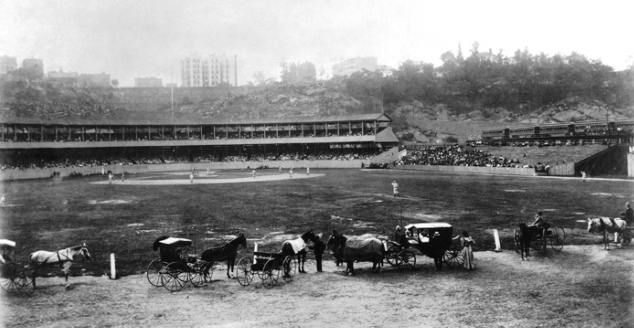

In the late 1800s, the “polo grounds” was a name used for multiple New York City ballparks where the sport of polo was played. The first Polo Grounds for baseball was located on the northern edge of Central Park between 110th and 112th Street at 6th Avenue.

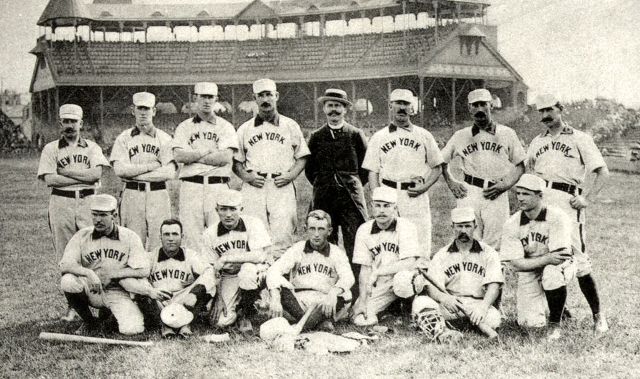

Here, in 1880, John Bailey Day rented land previously used for polo matches to construct a single-tier grandstand for his baseball team, the New York Metropolitans. In 1883, Day’s new National League Team, the New York Gothams, played their first game at the ballpark on May 1, 1883. A second deck was added to the ballpark that year, giving the first Polo Grounds a seating capacity of 12,000.

In 1889, the Giants moved to Coogan’s Bluff, an elevated area extending from 155th to 160th Street and overlooking the Harlem River. The bluff, along with a grassy knoll called Coogan’s Hollow, was named in honor of James J. Coogan, a real estate merchant who owned much of the property in that area. The land remained in the Coogan estate, and the Giants rented one of the two ballparks in the hollow. They played their first game at the second Polo Grounds in Coogan’s Hollow on July 8, 1889.

After the Giants played their last game at the second “polo grounds” (Polo Grounds II) on September 30, 1890, they moved to the adjacent field to the north, called Brotherhood Park. (There were actually two New York Giants franchises for a short time during this era; the Players’ League team played at Brotherhood Park and the National League team stayed at Polo Grounds II.) The Players’ League folded in 1891, and the National League team moved into the bigger ballpark. Polo Grounds II was renamed Manhattan Field and converted for other sports such as football and track-and-field.

The National League Giants played their first game at Brotherhood Park – Polo Grounds III — on April 22, 1891. The third incarnation of the Polo Grounds had a seating capacity of 16,000 and featured a double-decked grandstand that arched around home plate and down the baselines. Bleachers were located in center field.

By 1911, the ballpark was the largest stadium in baseball with seating for 31,000 fans. Built of wood, the ballpark caught fire and burned while the Giants were out of town on April 14, 1911. Following the lead of other teams, the Giants constructed their fourth and final Polo Grounds of steel and concrete. The team played its first game at the partially completed stadium on June 28, 1911.

The Cat Colony of the Polo Grounds

For many years, a colony of cats lived under the dark and cool stands at the Polo Grounds. In 1932, when the little black cat stopped the ballgame, the space under the stands was also used as storage for circus seats, so there were lots of places to hide.

Sometimes the luckier cats that didn’t run and hide would go home with women who came to the ballgames or with the ballerinas from the opera companies that performed at the Polo Grounds when the Giants were out of town.

The dean of the cat colony was groundskeeper Henry Fabian’s big black tomcat, Tiger. Tiger kept to himself in Henry’s tool shed near the left-field boxes, and he was always ready to defend his master when other cats tried to move into their territory. Henry denied charges that Tiger was the jinx at this ballgame.

Jack, the long-time assistant foreman in charge of sweepers, also kept several cats in his little cubbyhole where he stored his brooms. The cats, which he named Blackie, Wildcat, Little Red, Mickey, Big Blackie, Nig and Brownie, would all gather around him and rub his legs when it was time for supper. Jack admitted that while first baseman Memphis Bill Terry was the best player on the Giants, the ballplayer couldn’t hold a candle to his cat Brownie. “Brownie’s the best rat catcher I’ve got,” Jack said.

Jack told reporters that it cost him 30 cents a day to feed the cats – most of that budget went toward Wildcat, who always tore into the milk with gusto — but it was all worth it. “They’re more fun than a barrel of monkeys,” he said, while also denying that it was one of his cats that caused the ruckus during the Braves game.

The End of the Polo Grounds

With few fans, a stadium crumbling into disrepair, and a slew of tenement housing encroaching Coogan’s Bluff, Giants owner Horace Stoneham announced on August 19, 1957, that the team would move to San Francisco the following year (the Brooklyn Dodgers would also move to Los Angeles).

The Giants played their last game at the Polo Grounds on September 29, 1957. The ballpark sat mostly vacant for three years, until the newly formed Titans (present-day New York Jets) began to play there in 1960, followed by the newly formed New York Mets in 1962.

Although the Mets upgraded the stadium and made it their interim home while Shea Stadium was being built, the Polo Grounds was demolished in April 1964 with the same wrecking ball (painted to look like a baseball) used to take down Ebbets Field in Brooklyn four years earlier. New York City had already decided to claim the land under eminent domain – the Coogan family fought this takeover but lost in 1967.

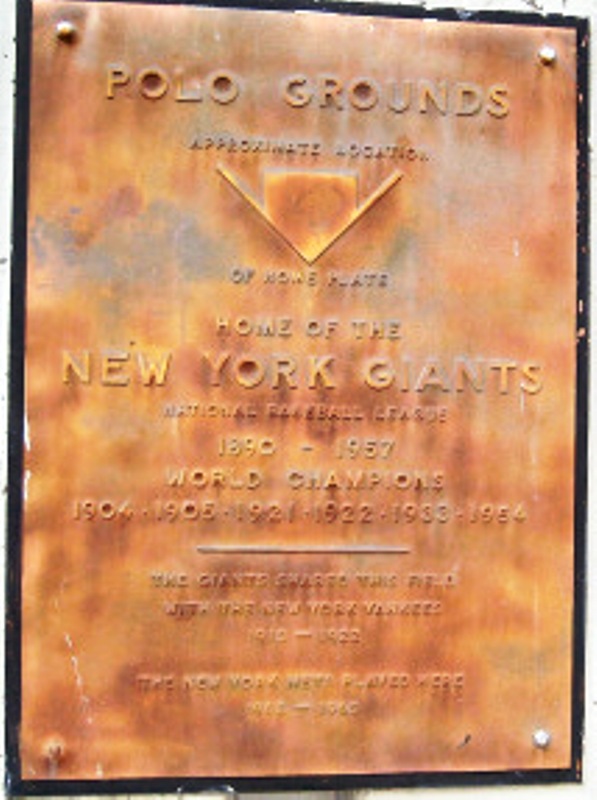

Today, the site is home to the Polo Grounds Towers, a public housing project opened in 1968 and managed by the New York City Housing Authority. Inside the complex is a faded plaque — supposedly placed at the approximate location of home plate — that commemorates the Polo Grounds. The only other reminder of Polo Grounds is the John T. Brush Stairway which leads down Coogan’s Bluff from Edgecombe Avenue to Harlem River Drive.

And who knows, maybe a few descendants of the Polo Grounds cats still make their home in the area…

If you enjoyed this story, you may enjoy reading about Ranger I and Ranger II, the black cats of the superstitious New York Rangers hockey team.

[…] should it be?” Westerby responded (unlike baseball players, hockey players were not superstitious when it came to black cats.) Unable to answer the question, […]