Mr. Brian Hughes died the other day at his farm in Monroe, N. Y., and with his passing New York lost its master jokesmith, the originator of countless practical jokes that made everybody laugh, even their victims. Although a successful banker and manufacturer, he was more widely known for his ability to joke than for his commercial successes.

His entire career was one of devastating jocularity. He lived to be 75 years old, and almost to the day of his death he was getting as much fun out of life as was possible.—The Galveston Daily News, Jan. 5, 1925

I discovered the late great Mr. Brian George Hughes while writing a story about Arson and Homicide, two cats that patrolled the old New York Police headquarters building at 240 Centre Street. As I was doing research on this building, I learned that the site had been previously occupied by the Centre Market.

Brian Hughes & Brother, a paper box manufacturer, leased offices in the north end of the market building at 242 Centre Street. It was here Brian played one of his greatest signature pranks.

In 1904, right about the time the city was considering the site of the Centre Market for its new police headquarters, Brian and his brother Hugh (his parents also had a sense of humor) decided that the building would be a good investment.

When they inquired about purchasing the building, the city comptroller told them the property was not for sale. The next day, Brian placed huge signs in the windows with bold lettering that read “THIS PROPERTY IS NOT FOR SALE. B.G. HUGHES, AMERICA.”

When the comptroller asked about the signs, Brian told him that he was giving the city free advertising by telling folks that the building was not for sale. The comptroller was not amused, but Brian got a good laugh. From that point on, Brian placed “Not for Sale” signs on all his real estate.

Nicodemus, the Female Tom Cat

One of Brian’s biggest jokes involved a stray cat that he purchased for a dime in 1895 from a young bootblack on Hester Street who was just about to drown it. According to one news report, Brian bought the cat because he was attracted to the cat’s six toes.

Although he originally intended to keep the cat at his factory to kill rats, the cat wasn’t a mouser (probably because Brian fed it too well). The dark gray cat did, however, hold its head at an “aristocratic angle” due to an injury he sustained when he was struck by a falling infant. That gave Brian an idea.

Brian Hughes took the cat home and had it carefully washed and brushed. Then he entered the cat in the National Cat Show as “the last of the Dublin Brindle breed.” He told the judges that the cat’s name was Nicodemus, by Bowery, out of Dust-Pan, by Sweeper, by Ragtag-and-Bobtail.

At the show, Nicodemus was placed on display on a silk cushion inside a gold-plated cage surrounded by roses and attended to by a woman in a nurse’s gown. According to The New York Times, one woman reportedly walked by and commented on how absurd it was for a cat to have its own nurse when so many children in the world did not receive half the amount of care and attention.

Each day of the show, an African-American livery footman by the name of Sam Smith would arrive with ice cream and chicken packed in the boxes of a celebrated caterer. A florist would also deliver flowers to the alley cat every day. The other cats, including those belonging to Mrs. Standford White, Miss Louisa (J.P.) Morgan, and Mrs. John J. Astor could only look on in envy.

Nicodemus created a great sensation at the show, and several offers of $2,000 and more came in for the former street urchin (even though Brian advertised him as “the $1,000 Cat Not for Sale”). He took a fifty-dollar prize in the class for brown and dark gray tom cats (there were no other winners in this sub-class).

Despite all the attention and great food, Nicodemus apparently did not like the high life. According to a report in the Rochester Daily Union and Advertiser, he broke away from his attendant on the last day of the show and disappeared. A few days later, however, he appeared at Brian’s offices in the old Centre Street market.

A year later, Brian pulled the stunt again with the same cat. But this time, the joke was on him when it was discovered that his “male” cat was actually female. Sure enough, the alley cat soon gave birth to two kittens.

Determined to have the last laugh, Brian pulled the trick again in 1899, this time disguising his name as Nairb G. Sehguh and making up a fabulous story for the organizers of the International Cat Show at the Grand Central Palace.

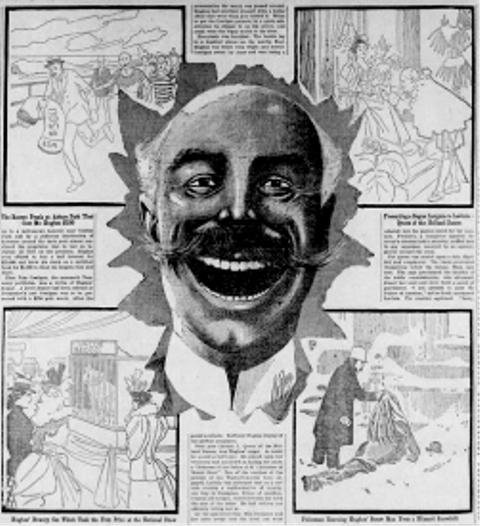

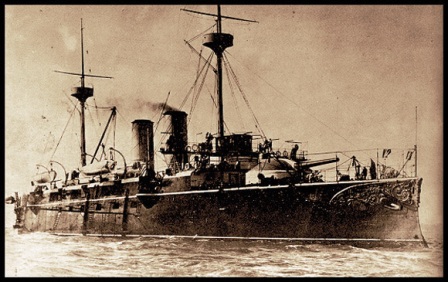

Brian said his new cat, Eulata, was a native of Hindustan who was once a mascot on the Spanish ship Vizcaya, and that when the ship sank in 1898 during the Spanish-American War, she swam to the USS Oregon and was rescued by sailors. As if that story wasn’t good enough, Brian also said the cat had been presented to the King of Spain by a Bombay merchant, who in turn presented her to Captain Don Antonio Eulate of the Vizcaya.

During the show, Eulata dined from silver dishes, slept on velvet cushions, and was occasionally sprayed with violet perfume. Her gilded cage was bedecked with fresh roses, violets, hyacinths, and carnations. On top were American and Spanish flags, a doll’s trunk labeled “Eulata,” and a box of food in a box stamped with “Sherry’s.” The cat had been completely shaved (save for her head and the tip of her tail) and was like nothing the judges had ever seen before.

This time, though, the judges figured out the joke when they realized that Nairb G. Sehguh was Brian G. Hughes spelled backwards.

Puldeka Orphan, the Old Car Horse

Since the cat pranks got so many laughs, Brian decided to try something similar with a horse in 1900. A few months before the National Horse Show opened at Madison Square Garden, he purchased an old streetcar mare from the Metropolitan Street Railway Company for $11.50. He got such a great deal because the horse was old and about to lose her job pulling a car on the 59th Street line to an electric trolley car.

Brian sent the horse up to his farm, Brightside, in Monroe, New York, and told his head stable man that he was entering her in the horse show. Brian said that every cent of the $500 prize money would go to the man who was able to get the horse into condition to compete. For the next two months, the old car horse got the lion’s share of attention in the stable.

The day before the show, Brian paid $24 for a special rail car to transport the horse back to the city. When the Garden show opened, Brian entered the horse as “Puldeka Orphan, by Metropolitan, dam, Electricity.” She was placed in a stall surrounded by flowers and attended to by two livery grooms. She looked absolutely majestic in the arena, with Brian’s daughter at the reins.

Now, everything would have gone smoothly, and Puldeka may have even won, had nobody noticed the small bell placed under her saddle. You see, Puldeka was used to hearing one bell (start) and two bells (stop), and didn’t know any other signals or “giddyup.” Miss Clara Hughes, Brian’s 18-year-old daughter, had to use the bells several times, which Brian said was what cost him the blue ribbon.

The funny thing is, although they noticed the bell, nobody noticed until the event was over that the name of the horse could be read, “Pulled a car often, by Metropolitan. Damn electricity.”

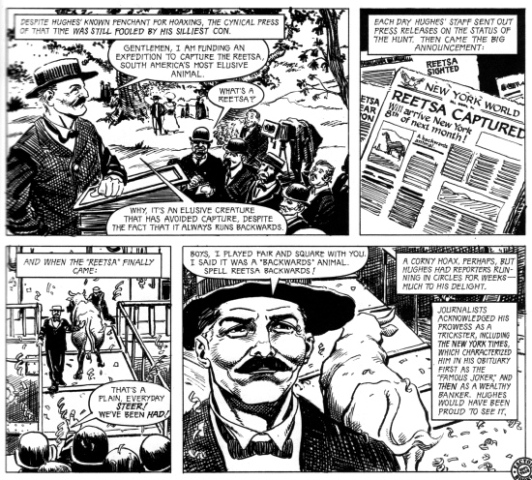

Another time, Brian claimed to have funded a South American expedition to catch a rare animal called a reetsa. For a year he supplied the media with updates about the expedition. Then he announced the capture and arranged for a ship to pull into the docks on the Hudson River. All the newsmen anxiously awaited for a chance to see this rare beast — which turned out to be a steer (reetsa spelled backwards).

The Man Behind the Practical Jokes

Brian Hughes was born in Ireland on May 16, 1849. He arrived in America in 1858, and soon thereafter pulled his first prank while living uptown.* Central Park was just being laid out at this time, and Brian would often play hooky to snare yellow birds from the area of the new park and sell them as singing canaries.

Brian married Josephine White of Boston in 1876 and the couple had three children: Gertrude Marie (later Mrs. John Joseph Burrell), Clara, and Arthur (who legally changed his name to Brian G. Hughes in 1909). They lived for a time in Brooklyn and also at 49 East 126th Street.

Little is known about his earlier life in New York or how he came to work in the box manufacturing industry. However, he became one of the most prosperous box makers in the city, and everyone seemed to know him, even though the only address he ever used was “America.” Almost any New York mail that was addressed “Brian G. Hughes, America” found its way to his desk.

Not All Fun and Games

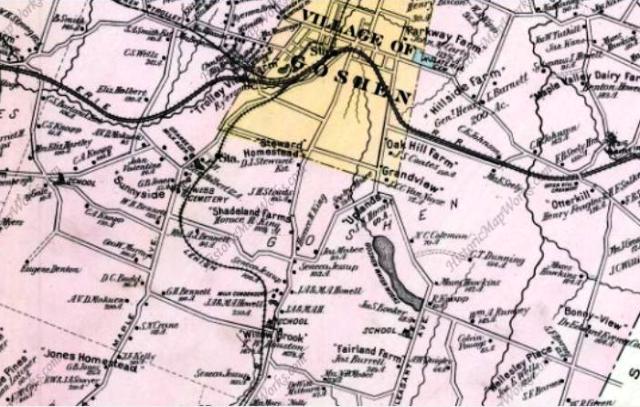

Although local and national newspapers often wrote about Brian and his practical jokes, the news was not always jovial. In 1910, several upstate New York papers reported on the grim discovery of Brian’s grandson, John Burrell, in a concrete ice house on Fairland Farm in Goshen, New York. The boy was still alive, but he had been confined to the small underground ice house for about a month.

According to the story, for some time there had been rumors among the farmers near Prospect Lake (today’s Goshen Reservoir) that Burrell had locked his son in the ice house. He was discovered by Fred Mann and Fred Mabee, two young neighbors who saw a farmhand entering the structure with bread. The health officer was summoned and the boy was taken to the State Hospital in Middletown.

Mr. Burrell told authorities that his son had been committed to an asylum on several occasions but could not be contained. He said the ice house was the only place he could keep him from destroying his property. The boy’s mother, Gertrude Hughes Burrell, was living in Harlem with the couple’s daughters at the time.

Two of the Burrells’ daughters, Josephine and Gertrude, were confined to the St. Vincent’s Retreat in Harrison, New York. Another daughter named Clara was a “spinster” who lived near Lake Sapphire Road in Monroe and died in Tuxedo Hospital April 7th, 1951.

A Permanent Moratorium on Jokes

On August 1, 1915, Brian’s wife died at Brightside in Monroe. Only 57, she had been in poor health for some time, and had left their city home on Madison Avenue in Harlem for the country about 6 weeks earlier.

Three years later, Brian Hughes became president of the Dollar Savings Bank in the Bronx. In light of this new position and the war, Brian told the public that he would put an end to the pranks.

Brian Hughes died at his home in Monroe on December 8, 1924. More than 400 people attended the services at the All Saints Church on Madison Avenue in Harlem. Reverend Patrick F. MacAran, founder of the Parish of St. Anastasia in Harriman, New York, officiated the mass. Brian was buried at Calvary Cemetery in Queens.

Four years later, at age 42, Brian G. Hughes, Jr. shot himself with a pistol in the Mulberry Street office just minutes after talking to his young bride, Margaret. His wife and secretary thought he was just pulling a practical joke, but when they went in to check on him, they found him dead on the floor. To this day, the motive remains a mystery.

* No census reports for the Hughes family from 1860 or 1870 could be located, which makes me wonder if Brian may have grown up in one of the many shanty houses occupied by Irish immigrants before Central Park was completed. Brian’s first pranks involved painting Central Park sparrows yellow in order to sell them as canaries to wealthy women.

[…] of Hurlbut Chapman’s Angora cats won prizes at the first annual National Cat Show at Madison Square Garden II in 1895. A year later, his cat Marie escaped from the […]

[…] Scenes from the 1895 National Cat Show at Madison Square Garden II. One of the cats that caused the biggest stir at this show was Nicodemus, owned by New York prankster Brian G. Hughes. […]

[…] box manufacturer and grand prankster Brian G. Hughes was leasing part of the Centre Market when it was purchased by the city for the police department. […]