Some sources claim that actor John Barrymore, a frequent guest of the Algonquin Hotel, changed Rusty’s name to Hamlet. Barrymore was a big fan of cats, and he did play Hamlet on Broadway, but every newspaper article from that era calls the cat Rusty. No news articles from the 1930s or 1940s mention a cat at the Algonquin named Hamlet.

In 1936, a rather disheveled kitten about seven months old stepped into the lobby of New York City’s Algonquin Hotel on 44th Street. Like most stray cats, he was fighting for survival on the streets, and a hotel lobby was as good a place as any to search (or beg) for food and shelter.

Frank Case, the legendary owner of the Algonquin, welcomed this feline hotel guest, even though he was just a ragamuffin street cat. Somehow he knew there was something special about this orange cat with the perfect tabby markings. Plus, the hotel needed a new cat to replace Billy, who had arrived at the Algonquin around 1921 and had lived there happily for 15 years.

Frank Case, the legendary owner of the Algonquin, welcomed this feline hotel guest, even though he was just a ragamuffin street cat. Somehow he knew there was something special about this orange cat with the perfect tabby markings. Plus, the hotel needed a new cat to replace Billy, who had arrived at the Algonquin around 1921 and had lived there happily for 15 years.

Frank Case named the cat Rusty, and well, as they say, the rest is history.

The Algonquin Hotel was built in 1902 following the demolition of two brick stables and two frame buildings on land once occupied by the farm of John N. Grenzebach. When it opened on November 22, it was a residential hotel with apartments that could be rented for an annual rate of $420 for a simple one-bedroom and bath to $2,520 for a luxurious suite of three bedrooms, private dining room, parlor, library, three bathrooms and private hallway. Museum of the City of New York Collections

Almost 80 years later, the iconic 12-story hotel at 59-63 West 44th Street still has a resident cat. In fact, in all these years, the Algonquin has never been without a feline host or hostess to great the guests. All but one of the Algonquin cats have been rescues.

Matilda III is the current cat of the house. She took over when Matilda II retired at the age of 15 and moved to a staff member’s home in December 2010. A beautiful ragdoll cat (although she sometimes reminds me of Grumpy Cat), Matilda III was rescued after being abandoned in a box outside the North Shore Animal League in Port Washington, New York.

The Legend of Rusty

Rusty, the Algonquin’s “snooty cat…ignores more celebrities than the Social Register…it’s whispered around by those who claim to know that he really runs the place.”– Dorothy Kilgallen, the “Voice of Broadway”

There’s not a lot of information about Billy — Frank Case gives him a cameo appearance in his book, Do Not Disturb — but Rusty often made the New York press headlines.

Over the years, Rusty grew into a very distinguished cat, weighing 18 pounds at his prime. He was a favorite among the actors and artists and writers that frequented the hotel, and he especially loved new guests.

Here’s Rusty at the bar having his daily champagne glass of milk.

Rusty would greet and nudge each new guest warmly and incorrigibly – he’d often have to be pushed off the register to they could sign it (what is it with cats and newspapers and books?).

In early years, the hotel allowed its temporary residents to have dogs, so Rusty had quite a few run-ins with canines. One time a French poodle that was staying at the hotel gave Rusty quite a tussle, and the poor cat hid under a bed for several days. He got sympathy cards from many famous people, including author Sinclair Lewis.

Rusty had a daily routine, which began every morning in the 10th-floor suite occupied by Frank and Bertha Case. Here, Bertha would prepare him for the hotel guests by grooming him. Rusty loved this ritual, and would run to Bertha as soon as he saw the brush in her hands.

Once presentable, Rusty would take the elevator downstairs to assist the Algonquin staff. For Rusty’s convenience, a little swinging door between the lobby and the kitchen was installed so he could help with the kitchen staff.

However, he spent much of the day in the Blue Bar with Louie the bar waiter, where he had a special stool reserved just for him. He’d show up for duty around 11 a.m. when guests began arriving, and keep guard until around 3 p.m. when the lunch crowd thinned out.

Rusty spent much of the day in the Blue Bar with his pal Louie the bar waiter.

When he finally had the bar and Louie to himself, Rusty would drum his front paws on the counter to demand his daily shot of milk. Sometimes Louie would whistle songs and Rusty would sort of sway to the music as if dancing.

Then promptly at 4 p.m. he’d jump off his stool and get back on the elevator in the lobby with his guardian, Mrs. Germaine Legrand, the Case family’s housekeeper (he always took the passenger elevator, never the service elevator!).

Back in the Case suite, Rusty would get a snifter of milk in a champagne glass and then take an afternoon cat nap. At 7:30 p.m., he’d appear at the bar again for his next tour of duty, and then head back upstairs for the night at 10 p.m.

In early years, the Algonquin offered an in-house physician, barber, hairdresser and manicurist who would make calls to rooms. It also had a barbershop for guests (I don’t know if Rusty had his own chair here, but I doubt he ever asked for a haircut!) Museum of the City of New York Collections

Summers at Southampton

Summers were extra special for Rusty, because he got to take a break from the big city and spend weekends at the Case family’s summer home, Shore Acre Farm, on Actors Colony Road in the village of North Haven (Southampton), Long Island.

Frank Case purchased the waterfront summer home in June 1919 from Mrs. Lilian Backus, the widow of Eben Y. Backus, who was the stage manager for the Empire Theatre on 42nd Street.

The home was located in a cottage colony of actors (hence the street name) and many famous thespians who also lived or vacationed at the colony, including Douglass Fairbanks and Mary Pickford, would often visit the family and their cat Rusty.

The Case summer home – formerly the Backus cottage (middle right) — was located just north of the old Charles M. Goodsell cottage and farm, where Julian Hawthorne, the son of author Nathanial Hawthorne, had spent a summer in 1820. The 92-acre estate on the Shelter Island Sound was purchased by the Sag Harbor Estates Company in 1910, which built a cottage park that they called Hawthorne Manor. The colony was purchased by the Conservative Land Associates in 1925, with plans to subdivide the land further for “high-class small homes.”—NYT, November 18, 1925

Rusty Dies of a Broken Heart

On February 21, 1946, five years after Rusty won a long battle with pneumonia, Bertha Case succumbed to a year-long illness and died in the Case’s hotel suite. Four months later, on June 7, Frank Case died in the hotel.

Following his death, Frank’s body was laid in state in the suite. John Martin, manager of the hotel, held Rusty in his arms and let him take a last look at his master. Martin told the press that as he held him, a shudder appeared to go through the cat’s body. He also uttered a strange cry.

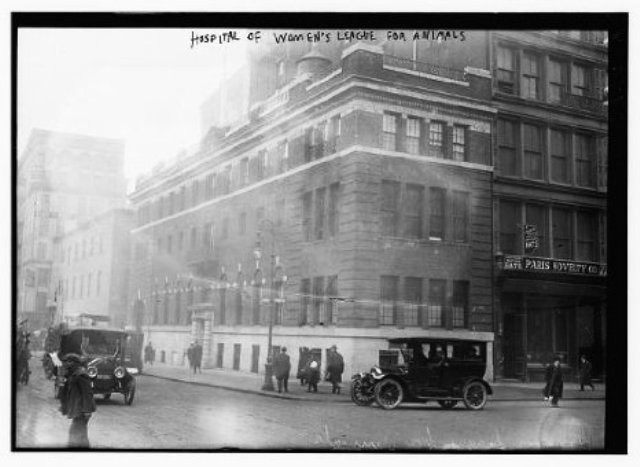

In April 1941, Rusty came down with pneumonia and had to spend some time in an oxygen tent at the Ellin Prince Speyer Animal Hospital for Animals at 350 Lafayette Street. Formerly known as the Hospital of Women’s League for Animals, the facility opened in 1914.

For several days, Rusty refused to eat or roam the premises. He no longer visited John Martin on Sundays, as he had done for years. John took him to the Speyer Hospital for Animals, where the depressed cat was diagnosed with jaundice complicated by leukemia.

Less than two weeks after Frank’s death, John found Rusty in the suite, curled beside the bed of his old master. The jaundice and feline leukemia were no doubt the cause of his death, but those who knew him, like Mrs. Legrand, said he simply died of a broken heart.

“Rusty was sick from missing the two people he loved best,” Mrs. Legrand told The New York Sun. “Always he was looking at the door as if he wondered why they didn’t come.”

According to the East Hampton Star (August 15, 1946), Rusty was buried in the place he spent many a summer day with the Case family and their famous theater friends — in the Case garden at their summer home in Southampton.

In 1924 Ben B. Bodne and his bride Mary (with Harpo Marx) honeymooned at the Algonquin. At the time, he promised Mary he would one day buy the hotel for her. Soon after Frank Case died in 1946, Ben Bodne retired from the oil business and acquired ownership and operation of the hotel.

Since Rusty’s passing, 10 cats have been king or queen of the Algonquin Hotel. Although most of the cats had full run of the place, that changed in 2011 with a directive from the New York City Department of Health, which required the hotel cat to remain in areas where food is not prepared or served.

I guess this 21st-century directive means there is no longer a special stool at the bar reserved just for the hotel’s feline and no longer a kitty door to the kitchen. Although he didn’t have a Twitter account, a Facebook page, or an email address, Rusty had it pretty good in those simpler, rule-free days.

Rusty was buried in the Case family garden at their summer home on Sag Harbor, somewhere in the vicinity of today’s Cedar Avenue. Considering the fact that all this land is now worth countless millions of dollars – even Richard Gere had a house nearby until recently – Rusty’s final resting place is pretty darn nice for a former alley cat.

Rusty received numerous letters from his fans, and every year he was recognized for donating to the March of Dimes, but that’s nothing compared to the attention Hamlet gets. As a formal feral feline (note his clipped ear) and a cat of the digital age, Hamlet is probably the most popular Algonquin Cat yet. He’s all over the Internet, and even has his own Twitter account, Facebook page, and email!

My Grandfather was Thomas Frank Hoey, he worked for Central park zoo as caretaker around the ’20s and ’30s. I have many photos and newspaper clipings from 1929.

Oh my gosh, did you read my story about Caliph Murphy, the hippo that saved the Central park zoo lion house? As soon as I saw your grandfather’s name I knew exactly who you were talking about! He makes a cameo in this story. I’d love to have a photo of him to add to this story or any future stories I do about the zoo. Let me know if you have a photo you’d like to share. Thanks!

https://bwl.kwr.mybluehost.me/2014/03/29/caliph-murphy-central-park/

Yes I have photos of the animals and some of my grandfather. I have a whole page clipping from the Telegram news in 1929. Feeding Queenie an orphand ewe that he raised since its mother abanded it. It also tells about my grandfathers life and stuff. He lived at 204 west end ave in ny city. I have a post card from a Mr. Smith to him dated 1912,with a Bison on it ,asking Mr. Hoey if his was as big as the one on the card. I have a clipping of Tom feeding two rams named Jimmy Walker and Hyland. News paper is very fragile. Yes I read the story. Thats where I seen my Grandfathers name.

Do you have an e-mail address I can send the pictures to?

Yes, you can send to pgavan@optonline.net Thank you!