“Hundreds of thousands have had an olfactory introduction to Barren Island, though few have ever visited it. It is a sea-washed bit of land a mile and a half long and three-quarters of a mile wide, just at the entrance to Jamaica Bay. There are few persons living on the adjacent coasts who have not been deeply impressed with its existence, for from its shores there has been wafted by the sea breezes and spread abroad more and worse odors of a stomach-turning description than ever emanated from a spot of similar size.” New York Times, November 7, 1890

No one knows where the hogs came from or when they first took up residence on Barren Island in Jamaica Bay. But according to an estimate by Dr. Walter Bensel, City Sanitary Superintendent, there were close to 1,000 hogs on Barren Island in 1909. That was about 999 too many.

In actuality, the hogs were the least of the worries when it came to Barren Island. To put it simply, the island stunk. It smelled so bad, in fact, that the odorous vapors emanating from Barren Island were making families living along Jamaica Bay sick, depreciating the value of their real estate, and driving away summer guests from Brooklyn hotels.

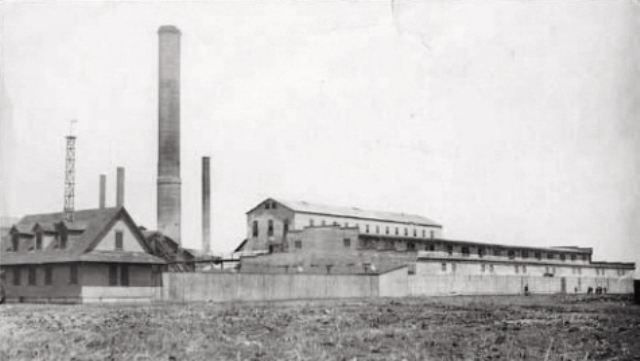

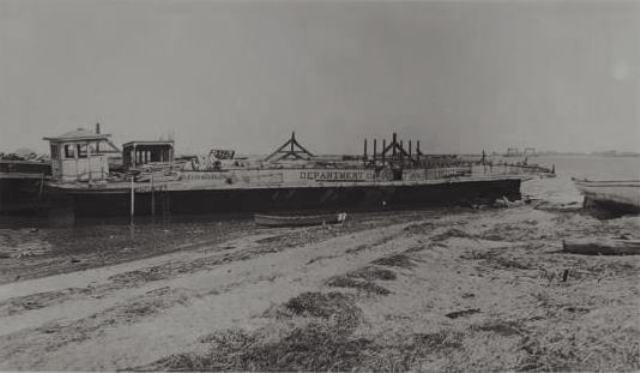

One of the reasons the island was so odoriferous was the fact that the predominant industries on the island in the late 1800s and early 1900s were stench-producing fish oil factories, fertilizer plants, and horse (glue) factories on the south shore. Hundreds of men worked in these factories, and by 1909, most of them were living on the island in shacks with their families.

If bone boiling, sludge acid, and decaying fish and animal flesh weren’t bad enough, the island was also the garbage dump for Brooklyn and a dumping ground for offal (the entrails of butchered animals) and dead animals, including horses, cats, and dogs.

But getting back to the hogs: Since 1907, Barren Island had been overrun with hogs. They roamed the island at will, breaking all the sanitary codes in the book. Complaints poured into the Health Department, causing Dr. Bensel to send an inspector to the island to canvass each house to find out who owned them. (The Board of Health was okay with the inhabitants owning hogs as long as they were properly penned.) At every house, the inspector was told that the hogs did not belong to the residents.

On the morning of March 16, 1909, a dozen policemen from the Health Department and Dr. Bensel took a power boat from Canarsie Landing in Brooklyn to Barren Island. Each officer was armed with 200 rounds of cartridges and ordered to kill as many hogs as possible. The moment the men stepped ashore a half hour later, the word started spreading that all the hogs were going to be killed.

As the police began shooting the hogs, many women began doing whatever they could to save the swine (there was no longer any doubt that the island residents owned the hogs). They began whistling and shouting and pleading with the officers to spare the animals’ lives. The men split up, with half going up the island in front of the houses and the other going in back of the yards.

As shots rang out non-stop, the women scattered over the fields to reign in their animals. Some men left their jobs at the factories to rescue their hogs and carry them into their homes. Many used pans of shelled corn to coax them into the back yards. Once there, the men carried the hogs into kitchens and even bedrooms to keep them safe.

Fortunately, few children witnessed the hog massacre as they were inside the public school. Dr. Bensel was kind enough to pick a time and day when the kids would be in school and not outside at recess.

By the end of the day, hundreds of hogs had been killed. Many escaped to the salt marshes where no man could follow them. Others who were saved by their owners were huddled on back porches or poking their noses into kitchens.

“If Roosevelt were only here!” said one officer who was on the New York City police force when former President Teddy Roosevelt was a New York City Police Commissioner. “It was a big mistake he wasn’t invited.”

A Brief History of Barren Island

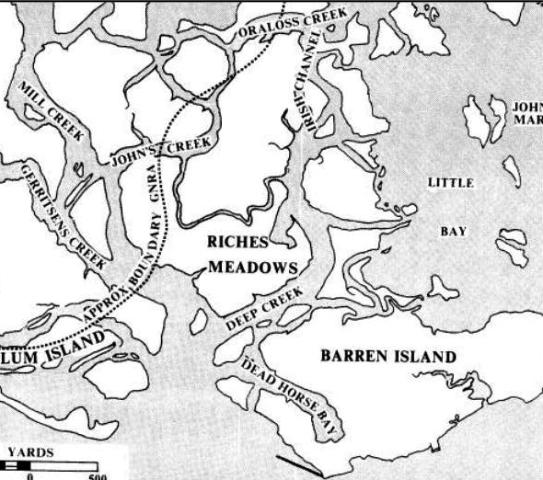

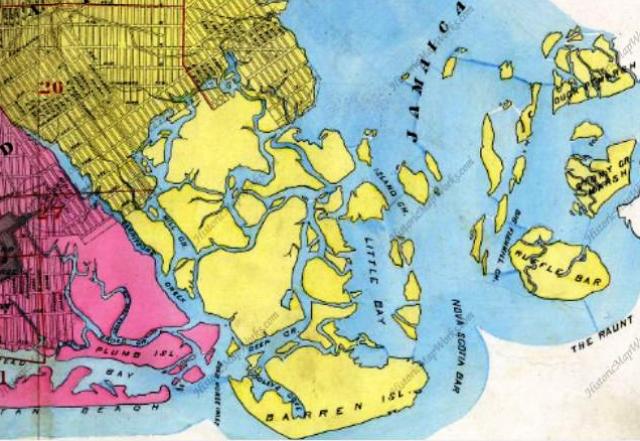

Barren Island was one of only three islands on the western side of Jamaica Bay that was inhabited or utilized during the Dutch colonial periods (the other two were Bergen and Mill islands). No one is really sure who owned Barren Island at any given time, but as early as 1664, several individuals laid claim to Barren Island or parts thereof, including William Moore and Rutgert Van Brunt.

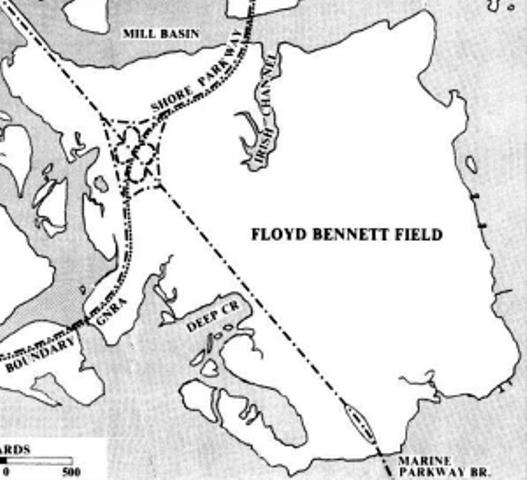

When it was still an “island,” Barren Island contained approximately 30 acres of upland and 70 acres of salt meadow. As only shallow streams separated it from the mainland at low tide, men and livestock could reach the island on foot. Small craft could access the northern shore, and larger vessels (like garbage barges in later years) could approach its southern edge. Pasturage for horses and cows and the harvesting of salt hay were the island’s main functions in colonial times.

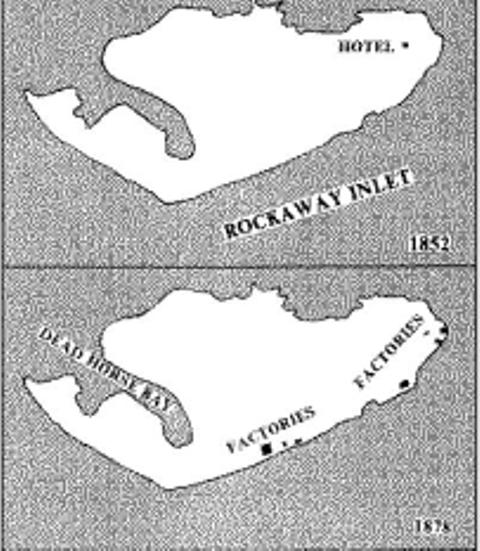

The island was pretty much uninhabited until the end of the 18th century, when a man by the name of Dooley built a house on the east end for entertaining sportsmen and fishermen. In 1830, John Johnson took over the Dooley house, which was designated a hotel on Dripps’ map of 1852 – and was the only structure noted on the island.

By the late 1850s, Barren Island had two fertilizer plants: One was built in 1859 by Lefferts R.Cornell and processed dead horses and other animals shipped from New York. The other was built around the same time by William B. Reynolds. From that time until the 1930s, the island had about 25 factories (no more than 7 or 8 at a time).

The Great Stink-Out

“What the Grand Canyon is to Colorado, the aroma of garbage and dead animals is, in a sense, to Barren Island.”

In the late 1890s, after receiving numerous complaints of the odors, both the state legislature and the city government made efforts to eliminate the Barren Island stench producers. These efforts failed, partly because the governor and mayor opposed to shutting them down (were the oil factory owners greasing their palms?), and partly because the city had no other plans for disposing its refuse. So the stench continued for many more years.

The island’s population peaked around 1905 with about 1,500 in inhabitants. During this period, Barren Island had two churches as well as the public school, three hotels, and four saloons. The residents also had their own pharmacy, butcher, bakery, and grocery stores.

Ferry service provided easy access to Rockaway, Sheepshead Bay, and Canarsie. The Canarsie Police Station was two and a half miles away, and police had a boat that they used to make trips to the island on a regular basis.

Floyd Bennett Field

In 1922, Judge Alfred J. Talley wrote a letter to Admiral Moffett, Chief of the Naval Bureau of Aeronautics, suggesting that Barren Island would be a great substitute for the discontinued naval air station at Rockaway Park. Talley happened to be the son-in-law of the late Andrew White, who then owned most of the island.

He noted that the island was now connected to Brooklyn via Flatbush Avenue (the avenue was extended to Jamaica Bay in 1921) and that the abandoned buildings could be made suitable for navy uses. There appears to be no followup on this suggestion.

In 1928, about 20 years after the great hog hunt, New York City commissioned Clarence Chamberlain to recommend a site for a new municipal airport. He chose Barren Island, which by that time already had a small dirt runway. This runway was referred to as Barren Island Airport and was used primarily by Paul Rizzo, who established the runway in 1927 to take customers on joy rides.

The new municipal airport was created by connecting Barren Island and a number of smaller marsh islands to the mainland by filling the channels with six million cubic yards of sand pumped from the bottom of Jamaica Bay. The airport was named after Navy warrant officer Floyd Bennett, a Brooklyn resident who co-piloted the first flight over the North Pole in 1926.

Floyd Bennett Field was dedicated on June 26, 1930, and officially opened on May 23, 1931.

The End of an Era

By 1930, the factories, school, stores, and most of the island residents were gone. All that was left were two dozen clapboard shacks, the skeleton of an old fertilizer factory, a church, and about 25 families (mostly Irish, Polish, and Italian) on the eastern end. Each household paid $10 to $12 in monthly rent, or $3 in water taxes if they owned their own homes.

Since the factories had all closed (only the garbage plant was still operating), most of the men lucky to have jobs during the Great Depression commuted to Manhattan. The women stayed on the island to care for the cows, ducks, chickens, and goats (try to picture this with planes flying ahead) while the children attended school in Brooklyn.

In the spring of 1936, the city’s parks commissioner, Robert Moses, condemned Barren Island to build the Marine Parkway Bridge. The few remaining families were given 30 days to leave. Although a few people moved their shacks to a corner of the island that was still privately owned by the White estate, most of the residents left the island. Their cottages were bulldozed and the colony was dispersed without ceremony.

The federal government purchased the White tract in 1942, putting a final end to the final hold-outs of Barren Island.

Another extremely interesting blog post on your A to Z Challenge theme – it’s like reading a chapter in a fascinating book – you leave me in total awe of your writing skills 🙂 Special Teaching at Pempi’s Palace

Thank you so much! BTW, I took a little “trip” over the pond to check out your blog, but I wasn’t able to post a comment because my website doesn’t use the WordPress URL. But it was nice to “meet” you (and I see you’re a fellow cat lover!).

[…] More> Barren Island, Brooklyn […]

Thanks for posting the information and the photos of Barren Island. My great-great-grandparents immigrated from Germany around 1855-1860 and raised their kids on Barren Island. As a boy, my great-grandfather tended bar in one of the three hotels. My grandfather said that to get to school, he and his brother would row to the mainland and then take a horse-drawn coach to the school. Your post here, and the photos, help bring that period to life. I cannot imagine living on the island at that time. Whoever we are, our ancestors were mighty hardy people, and we should be thankful for that.

So glad you enjoyed the story and that it gave you an opportunity to “see” what life was like for your grandparents!