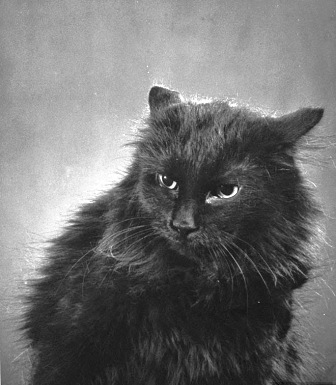

“The love of a man for a dog is as nothing compared to a hockey player’s love for his cat.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, article about the New York Rangers, February 6, 1931

As I’m writing this post, I want to point out that Albert the Dog has just named me one of his top 5 favorite New Yorkers for the month of May. Who happens to share this great honor with me? Why, it’s Henrik Lundqvist, the former goaltender for the New York Rangers!

If you’re a New York Ranger fan, or just a big hockey fan in general, you may have heard of the Curse of 1940, also called Dutton’s Curse.

The curse was a superstitious explanation for why the New York Rangers did not win the league’s championship trophy after 1940 for another 54 years. Some say the curse was caused when the management of the Madison Square Garden Corporation symbolically burned the mortgage for the arena in the bowl of the Cup after the 1939-40 season. I say there was no curse at all.

The reason the Rangers didn’t win the Stanley Cup during all those years was because the team no longer had their black cat mascot.

Okay, I know that if you’re a New York Rangers fan, you’re saying to yourself, hey, the New York Rangers don’t have a mascot now, and they never did. True, they are one of only three NHL teams today that don’t have a silly costumed mascot (like the New York Yankees, they’re too cool for a dopey mascot), but in the 1920s and 1930s, they did have a real cat mascot named Ranger (and later, Ranger III).

New York Rangers trainer Harry Westerby discovered Ranger in the winter of 1927. The little girl cat was cold and whimpering outside the steel door of the hockey dressing room in back of Madison Square Garden III, so Westerby brought her indoors.

When team manager Lester Patrick saw the cat in the dressing room, he asked Westerby about it. “Don’t you think a black cat’s unlucky?” he asked him.

“Why should it be?” Westerby responded (unlike baseball players, hockey players were not superstitious when it came to black cats.) Unable to answer the question, Lester Patrick agreed to let the cat stay. He’d never regret the decision.

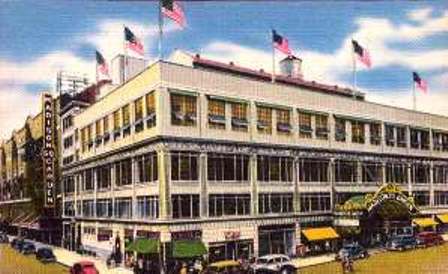

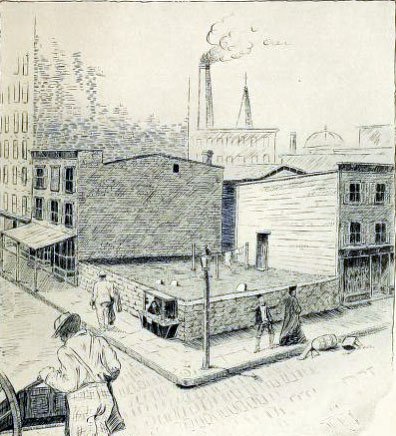

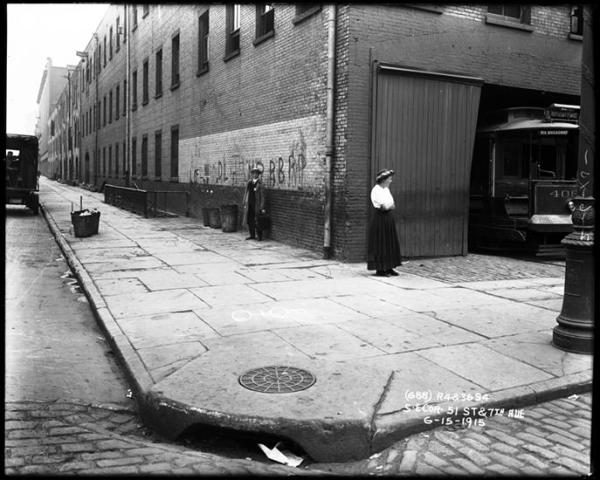

Madison Square Garden III

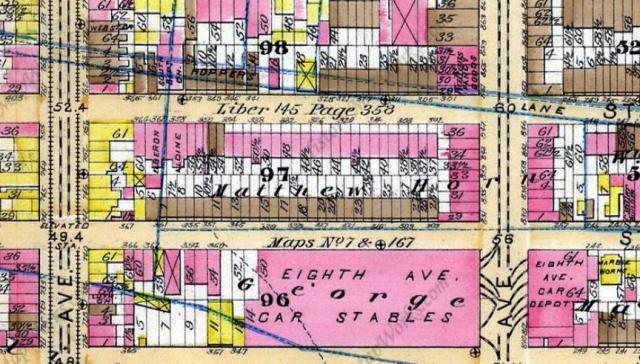

Madison Square Garden III was built in 1925, shortly after the more famous Madison Square Garden II was demolished by the New York Life Insurance Company. The new Garden was built on the site of the 18th-century Hopper Farm, aka, The Great Kill Farm, a large 300-acre estate that extended from about 6th Avenue to the Hudson River between 48th and 55th Street.

The Great Kill was a small stream that emptied into the Hudson River at the foot of what is now 42nd Street. All the territory north of this stream was called the Great Kill region.

Originally established by descendants of Andries (Andreas) Hoppe (no “r”) and his wife, Geertje Hendricks, Dutch settlers who came to New Amsterdam in 1652, the farm was acquired by Matthys (Matthias) Hopper in 1714. Matthias built his home just north of Hopper’s Lane (a diagonal road that ran between today’s 51st and 53rd Street) and west of Broadway. With most of the upper Great Kill region owned by the Hopper family, the area became known as Hopperville.

Sometime around 1750, Matthias’ son, General John Hopper, a soldier in the Revolution, took possession of the farm. He in turn gave each of his four sons acreage and a house. His oldest son, John, inherited a home at the terminus of Hopper’s Lane near the Hudson River; Yellis received a home on 51st Street between Broadway and 8th Avenue; Matthew got a stone house at the foot of 43rd Street (near today’s 11th Avenue); and his youngest son, Andrew, inherited the stone and brick homestead on the northeast corner of 50th and Broadway.

In later years, the land on Eighth Avenue between 49th and 50th Street was occupied by the Eighth Avenue Railroad Company stables. These wood frame stables were constructed sometime around August 1852, when the Eighth Avenue Railroad opened its new line between 51st Street and Chambers Street.

The stables were destroyed in a horrific fire in November 1879 that started in a fourth-story hay storage area and killed approximately 130 of the 950 horses stabled there. A year later, the railroad company replaced the stables with a three-story brick structure constructed by John Correga.

The Largest Arena in the World

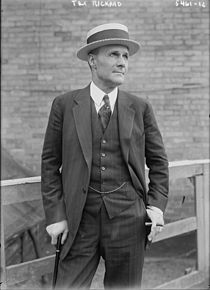

In June 1923, boxing promoter George L. “Tex” Rickard and a team of wealthy businessmen formed the New Madison Square Garden Corporation and proposed building “the largest indoor arena in the world” along with a 26-story office building on 7th Avenue and 50th Street, which was then occupied by the car barns of the Broadway-Seventh Avenue Railway Company. The Madison Square Garden Corporation comprised Tex Rickard, president; circus man John Ringling, chairman of the board; and William F. Carey, VP and Treasurer.

At the same time, circus man Frank Bailey, chairman of the board of directors of Realty Associates, was making plans with Bing & Bing of Brooklyn to build the largest amphitheater in the world on the same site.

Unfortunately for Rickard, the 7th Avenue sale got held up in ongoing litigation. So when the New York Life Insurance Company announced plans on June 17, 1924, to demolish the old Madison Square Garden — giving Rickard until August 1, 1925, to vacate the premises — Rickard and his associates decided they needed to move ahead with a new plan rather than wait for a settlement. That same day, Rickard announced that they had purchased the old trolley depot from the Eighth Avenue Railway Company for $2 million.

On January 9, 1925, 400 men began wrecking the old trolley depot to make way for the new Madison Square Garden. The new Garden’s gala opening took place December 15, 1925.

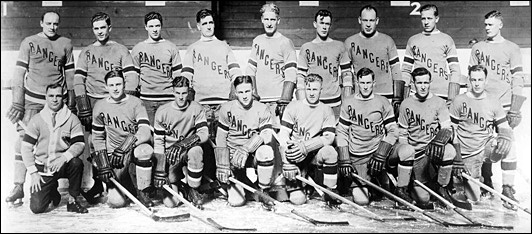

That year, the New York Americans joined the National Hockey League, becoming the second team to play in the U.S. The team proved to be a great success at the new Garden, which encouraged Tex Rickard to seek his own franchise. Rickard originally planned to name his new team the “New York Giants,” but when the franchise was granted in April 1926, the official name was the “New York Rangers Professional Hockey Club.

Ranger Brings Good Luck to Her Team

Ranger I was described as a fighting hockey cat that snarled and used her claws while boxing with feline opponents (the cat equivalent to throwing off the gloves). She was also quite charming — a good-luck charm, that is — for the Rangers during their successful 1927-28 season. That season, 10 teams played 44 games each, with the New York Rangers winning the Stanley Cup by beating the Montreal Maroons three games to two.

The team was so successful that year, in fact, that many of the players became minor celebrities in New York. Playing so close to Times Square also earned the Rangers their now-famous nickname, “The Broadway Blueshirts.”

Although the Rangers did not take the Cup during the next two seasons, the guys still considered Ranger to be their good-luck mascot. In fact, as long as Ranger I was patrolling the Garden, the Rangers were always in the playoffs.

Ranger stayed with the team for almost four years, but during that time she remained fairly wild, except with Harry and a few of the players. She also had several litters of kittens, but as soon as the kittens grew up, she’d shew them away from the Garden to fend for themselves — it was as if she knew she was the mascot and didn’t want any competition.

In January 1931, Ranger started refusing to eat and drink. Westerby would lock her in a room and bring milk and raw meat, but she’d barely take a bite.

Then one night as Westerby was coming back from his own supper, a group of employees called him over to that same steel door where he had found Ranger four years earlier. He dropped to his knees and started petting and cooing the poor cat, and then called for some brandy so she wouldn’t suffer. Ranger was “cremated” in the big furnace at the Garden – the same furnace where she kept warm on winter nights.

The day she died, January 10, 1931, all the hockey players, ticket-takers, and doorkeepers at the Garden mourned her passing. After losing a game the following night, Bill Cook, the team’s first captain, told the press, “That’s why we lost to the Black Hawks Sunday night. We’d already lost our mascot.”

The Rangers went without a win for more than a week, losing five and coming in tied in the eight games after Ranger’s death. By this time, the cat-less Rangers were in fourth place.

“You’d better get a new mascot in here in a hurry,” Bill Cook told management. “If you don’t, I’ll go out on the back fences, looking for one myself.”

Ranger III

Bill Cook didn’t didn’t have to look on the fences to find the team’s next mascot. As luck would have it, one of Ranger’s youngest offspring, whom the team called Ranger III, was living with the Rangers’ publicity man, Willis “Jersey” Jones. (Another of her kittens, Ranger II, was living in Nutley, N.J., but was too old at the time to be a mascot.) Jersey Jones told the team he’d bring the young cat to the Garden to serve as their new mascot.

“Ranger III is a carbon copy of the old lady,” Jersey told the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on February 3, 1931. “It’s marked the same kind of a way and is the same fresh kind of a cat – all claws and scratchy disposition. It’s grown up, too, since I took it home. The other day it killed his first mouse.”

On February 5, 1931, Ranger III was put to the test against Pete, the big black Newfoundland mascot dog of the rival Americans. Following the Ranger’s win, the young cat looked quite smug as she gave herself a bath under a table in the dressing room, while Pete moped about the American’s locker room.

The players warned the reporters not to step on the cat after the game. “If you do there’s going to be a couple of dead reporters around here,” Murray Murdoch said.

Ranger III disappeared a few seasons later. No one knows where she went, and no other cat ever replaced her as the New York Rangers mascot.

Madison Square Garden III disappeared when it was demolished in 1968-1969. The space remained a parking lot for 20 years, until William Zeckendorf Jr. and Victor Elmaleh of the World Wide Group purchased the property to construct the Worldwide Plaza office skyscraper.

Thanks for the fascinating history lesson!

Great story, thanks for sharing!

So glad you liked it — I’m a Ranger fan, so I thought it was really cool that they had a black cat mascot one time!

Sorry for the follow-up, but do you have any more information on Harry Westerby, the trainer? I’m interested in writing a story on him. Feel free to email me at duncanhennes@gmail.com

[…] Leake purchased a tract of about 80 acres between present-day Broadway and the Hudson River from Matthew Hopper. Much of the property west of the Eleventh Avenue comprised “sunken lands” that […]