In the 1600s, the island of Manhattan comprised New Amsterdam and Harlem. These settlements were separated by wilderness inhabited by Native Americans and wild animals, including wolves. According to James W. Beekman, president of the New York Historical Society in 1869, as late as 1685 there was a proclamation granting the permission to hunt and kill the wolves found on the island. But by 1891, no one expected to see a wolf roaming Manhattan, especially on the Bowery in the crowded Lower East Side.

The Wolves of the Bowery

Sometime around 1889, three young wolves were captured in the woods of Idaho and brought to New York to be tamed and trained for the dime museums. In October 1890, the wolves started their “career” on the stage at Huber’s Palace Museum at 106-108 East 14th Street. The performance was billed as “Little Red Riding Hood and her pack of tamed wolves.”

A year later, the three little wolves made their debut at the Globe Dime Museum on the Bowery, at 298 Bowery Street.

According to a report in The New York Times on August 26, 1891, by the time the wolves had arrived at the Globe, they had gotten much larger and stronger, and had begun to handle Little Red Riding Hood “rather roughly.” A big doll was substituted for a live girl during some of the scenes, but “the wolves found no pleasure in worrying a dummy, and the Bowery audiences also saw no fun in looking at wolves tearing up a bundle of rags.” (Would they have preferred the wolves tear up a live little girl on stage? Honestly, you can’t make this stuff up.)

Realizing that live wolves were no longer practical, Thomas Meehan and James Wilson, the proprietors of the Globe Dime Museum at this time, offered the two-year-old wolves to Superintendent William A. Conklin of the menagerie at Central Park. On Monday afternoon, August 25, 1891, a delivery driver from the park came to pick up the wolves and bring them uptown to their new home.

The three wolves were placed in a large crate made of wooden slats and loaded onto the truck. The driver had gone only about four blocks from East Houston Street when he noticed that several wooden slats were missing from the crate. One wolf was also missing.

The driver secured the crate with cords to prevent the other two prisoners from escaping and began to search for the wolf on the lam.

The History Behind 298 Bowery

Long before there was a Globe Dime Museum at 298 Bowery, and way before three wolves began terrorizing Little Red Riding Hood there, 298 Bowery was a farmhouse, a livery stable, and later, a saloon called The Cottage and The Gotham. The history of the building is quite interesting.

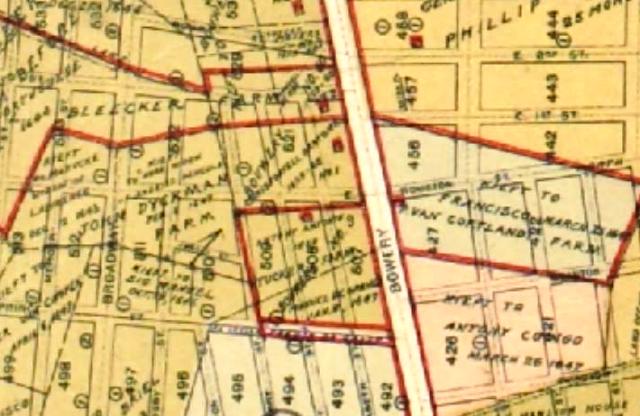

The Bowery was originally a Native American footpath that extended the length of the island through dense woodlands. Around 1642 or 1643, Director General William Kieft granted parcels of land (about 8 to 20 acres each) along this path to several superannuated slaves who had served the government from the earliest period of the Dutch settlement. Other parcels were granted to “free negroes” in the 1660s by Governor Richard Nicholls and Peter Stuyvesant.

Over the next 100 years, these lands passed through various hands and were combined to create much larger farms or bouweries owned by prominent settlers such as John Dyckman, James Delancey, and Nicholas Bayard (a bouwerie was a complete self-sustained farm, with crops, orchards, and livestock). These settlers widened the trail for use as a major roadway that connected the heart of the city in New Amsterdam with their bouweries. The Bouwerie Lane was anglicized to Bowery Lane and later, Bowery Street or the Bowery.

The Cottage and The Gotham

The original farmhouse at 298 Bowery was built about 1778 on land once occupied by the John Dyckman farm and homestead (the land had actually been taken over by a British Tory during the Revolutionary War, but he reportedly fled to Halifax after the war ended).

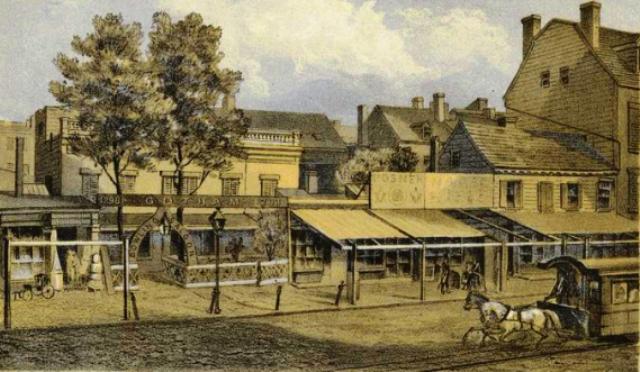

Being in close proximity to the Boston Post Road and just two miles outside the city limits, the house served as a roadside inn called “The Cottage” from about 1800 to 1820. Under the management of Samuel Verplanck of Sleepy Hollow, NY, The Cottage was very popular with farmers from Westchester County and drovers doing business at the Bull’s Head Cattle Market.

Over the years it was refurbished, and in April 1831, a private sale in the New York Evening Post described 298 Bowery as follows:

“That elegant 3 story house and lot…23 x 100 foot deep, built by days work, finished with sliding doors, marble mantels and grates in the principal rooms, balconies in the rear to the first and second stories, a grape vine covering the same; the garden stocked with choice plants; an alley leading from the lot to the street above. The property will be sold a bargain.”

I’m not sure if the house was ever sold, but in 1831, Harry B. Venn, a noted volunteer fireman with Columbian Hook and Ladder Company No. 14, was leasing the property and operating a saloon called the Gotham Saloon. S.W. Bryham took over the saloon in 1836 and renamed it the Bowery Steam Confectionery and Saloon.

Around 1841, under the management of Edwin Parmele, who owned a bowling saloon at 340 Pearl Street, 298 Bowery was known as the Bowery Cottage. During this time, the saloon was the headquarters for volunteer firemen, sporting men, and Bowery B’Hoys.

Harry Venn resumed proprietorship sometime before 1845, and attempted to turn the saloon into a miniature Vauxhall Gardens with a concert saloon for musical performances. When that didn’t pan out, he replaced the concert area with three 10-pin alleys for bowling.

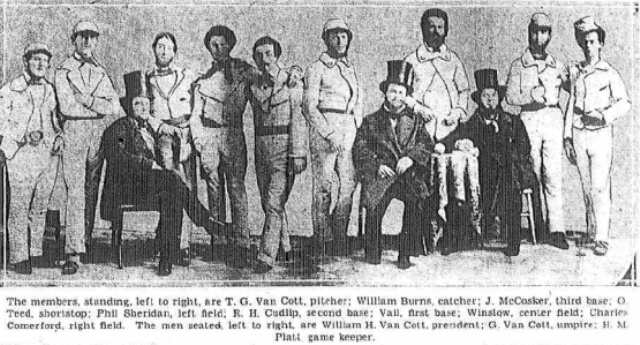

During this era, the saloon, now called The Gotham, was headquarters for the Gotham Base Ball Club (aka, Washington BBC and New York BBC). Gilded trophy balls from victorious matches were on display in a case behind the front bar, and the back bar featured a big gilt number 6 taken from the Americus Fire Company No. 6, aka, the Big Six (Boss William Tweed was foreman of this company and was a frequent patron of The Gotham).

On December 27, 1854, the Exempt Engine Company was organized at The Gotham under the leadership of Harry Venn. The Exempt was composed of firemen who had served their time and had been honorably discharged. They were called out only in extraordinary emergencies, such as during the Draft Riots in 1863 and when Barnum’s American Museum burned down in 1865.

In 1858, the establishment was turned over to Edward Bonnell, a popular volunteer fireman and foreman of Tompkins Hose Company No. 16. Edward made numerous improvements to the building, and enlarged the public accommodations to render the apartments as “convenient, cozy and desirable as the best-furnished parlors of a Broadway hotel.” Under Bonnell’s management, The Gotham was recognized as the fraternal headquarters for volunteer firemen all across the United States.

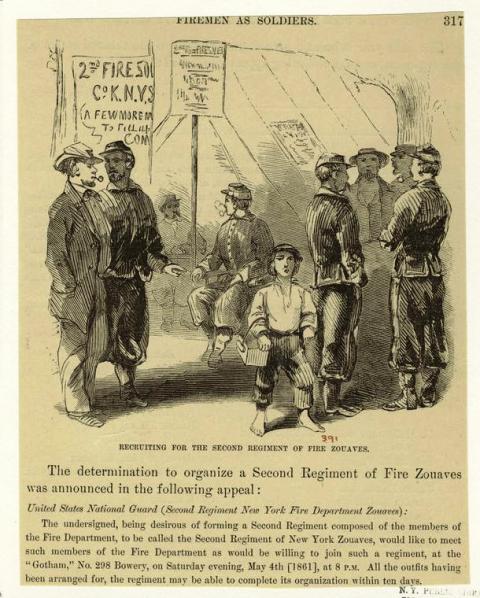

During the Civil War era, The Gotham featured a drill room in the back of the tavern for the voluntary infantry regiments, and Richard Burnton operated a book and stationery shop in the front. Many organizations like the Boss Bakers’s Association of New York (formed 1862) also held meetings there. (I wonder if they shared their baked goods with the infantrymen?)

The End of The Gotham

During the saloon’s final decade, things got a little dicey. Under the management of John Matthews, a man was murdered there in April 1871, and the police closed the establishment on several occasions on complaints of persons who had lost money there while gambling.

On April 29, 1878, the New York Tribune reported that the Gotham Cottage was being torn down. Architect Charles Mettam designed a four-story, four-bay brick museum/music hall and lodging house in the Neo-Grec style to replace the old saloon and lodging house. Mettam also designed two identical buildings at 300 and 302 Bowery, which housed Spencer’s Palace Music Hall.

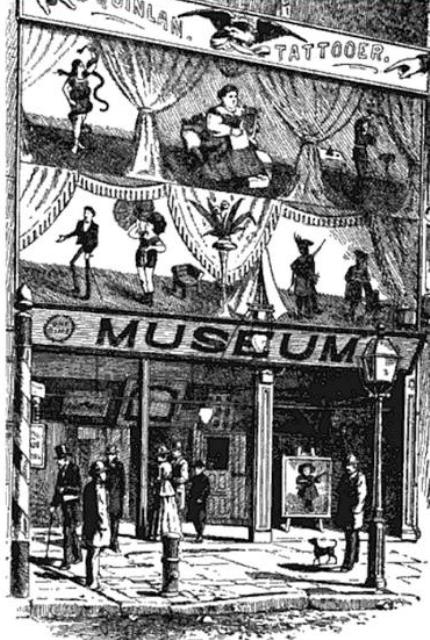

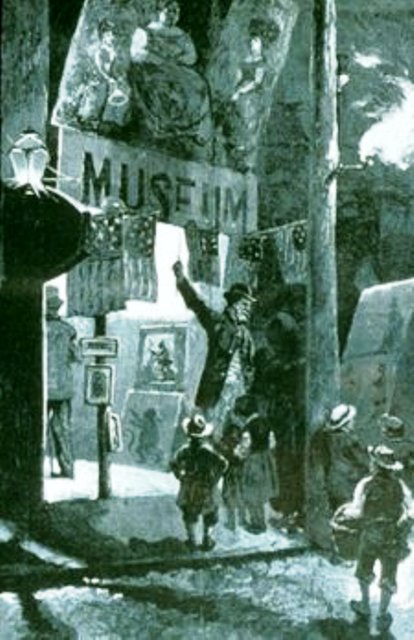

As the new building was going up, George B. Bunnell, a protégé of P.T. Barnum, secured a lease from owner Georgiana English. He opened his Great American Museum on January 27, 1879. Just four months later, on June 1, 1879, all of the contents of the dime museum, including “an educated pig,” were destroyed by a fire that completely gutted the building’s interior.

Circus man George Middleton came in and made repairs, and opened the Globe Dime Museum just a few months later. On May 25, 1880, fire struck again and most of the contents were destroyed. Middleton made repairs again, and the museum was fairly successful during the next 10 years.

Incidentally, on July 20, 1880, architect Charles Mettam received a patent for fireproofing iron columns used in building construction. In his filing dated April 14, 1800, Mettam described his idea:

The object of my invention is to fireproof the ordinary hollow iron columns of a building by filling them with water, so that in case of fire the columns will remain comparatively cool, and therefore perfectly safe from the usual disastrous effects of heat, and at the same time they shall be free from the danger of exploding from the steam arising from the water within when the columns are heated, and also free from the danger of bursting by the water therein becoming frozen.

Which brings us back in time to the wolf.

While the Central Park driver was looking for the escaped wolf, a woman and two young boys headed over to the Globe Dime Museum to report that they had seen a delivery man pick up the wolf and drive off with him around 5 p.m.

It turns out that Thomas Whalen of 207 West 41st Street, a driver of an evening paper delivery wagon, was making deliveries when he saw a crowd gathered near Fourth Street. “It’s a wolf! It’s a wolf!” the little boys were screaming. Whalen jumped off his seat and approached the wolf, who appeared to be confused by all the noise.

Although he assumed the wolf must have come from one of the Bowery dime museums, Thomas brought the wolf home and called Mr. Conklin the next day. Eventually, all three wolves made it to Central Park, where they joined one other lone wolf in custody at the menagerie.

During the 1880s and 1890s, the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children – and particularly Elbridge T. Gerry – went on a crusade to shut down the Globe Dime Museum and other establishments like it for exploiting children and attracting children to a “morally unfit environment” that encouraged prostitution and homelessness.

Over the years, 298 Bowery has seen many businesses come in go, including the Wood Mantel and Pier Mirror Company and Levy Bros. in the early 1900s and the Trenton Hotel China Company in the 1940s. From the late 1960s to the 1980s, the building was occupied by J & D Brauner (aka The Butcher Block).

Today the 137-year-old building is occupied by Chef’s Restaurant Supply, which is listed at 294-298 Bowery. Sounds like a good place for the old Boss Bakers’ Association to hold a reunion.

[…] Rosy had been purchased by another dealer named John Robinson, and was scheduled to go on exhibit in one of the city’s dime museums — perhaps P.T. Barnum’s American Museum on Broadway. As she awaited her transfer, Rosy was temporarily housed in a large tank at Donald Burns’ animal emporium, which, at the time, was also serving as a temporary home for 11 wolves that were starring in a play at the Globe Dime Museum (one of which escaped on August 25 of that year.) […]

[…] first met dime museum proprietor George Bunnell in my post about a wolf that escaped on the Bowery in 1891. A protege of P. T. Barnum, George Boardman Bunnell played a large role in the development […]

[…] volunteer fire department. (The Exempt Engine Company was organized on November 14, 1854, at the home of H.B. Venn at 298 Bowery, a building with a very interesting […]