May it be long before Muff’s gracious personality requires an epitaph, but when that time comes, the following lines will apply to him as fitly as to the one for whom they were written, the poet Whittier’s cat, Bathsheba:

“Whereat none said ‘Scat!’

Better cat never sat

On a mat, or caught a rat,

Than this cat. Requiescat!”

–Famous Pets of Famous People, Eleanor Lewis, 1892

For much of the first half of the 19th century, the Upper East Side of Manhattan remained very rural, to say the least. Most of the territory – about one-seventh of the acreage of Manhattan — had been owned by the city since the 1686 Dongan Charter of the City of New York, which granted to the city “all the waste, vacant, unpatented, and unappropriated lands.” The city maintained possession of these common lands for over a century, but would occasionally sell off small parcels and make them available under 21-year leases to raise funds for municipal projects.

During the late 1700s and early 1800s, many of the parcels in the Upper East Side were purchased by wealthy New Yorkers as speculative investments in anticipation of a real estate boom. One of these men was Isaac Adriance, an early member of the St. Nicholas Society of the City of New York who bought a considerable amount of land along Fourth Avenue (present-day Park Avenue) from about 50th Street to Harlem.

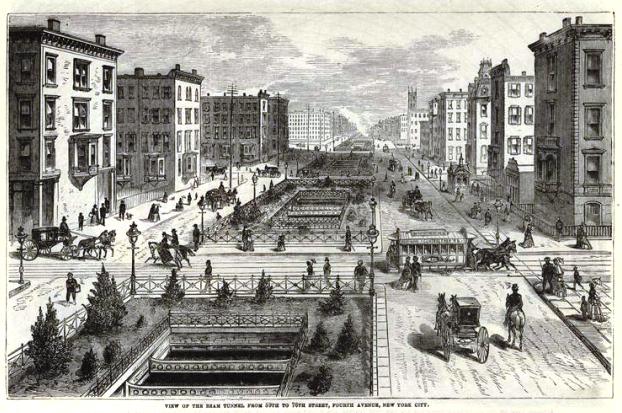

Development of the Upper East Side began in earnest with the chartering of the New York & Harlem Railroad (NY&H), which opened a double-track horse-car line along Fourth Avenue from 23rd Street to the hamlet of Harlem in 1837. The opening of Lexington Avenue and the construction of Central Park in the 1850s also drove up the value of real estate on the Upper East Side.

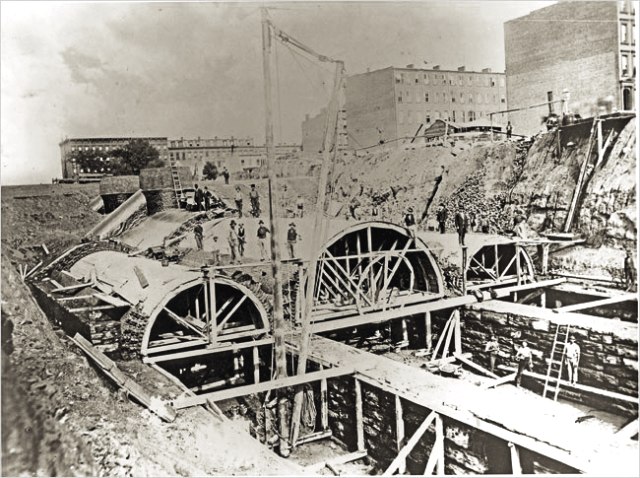

In 1872, the city and the railroad initiated the Fourth Avenue Improvement Scheme to help alleviate some of the locomotive dirt and noise that was now rendering the avenue an undesirable place to live. The railroad — now the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad — was widened to four tracks and placed within a tunnel from 59th to 96th Street. Above 96th Street, open-cut stations were constructed, like the Harlem station at 124th-125th Street.

The plan worked pretty well, however, and soon numerous tenements and row houses were built along Fourth Avenue from 42nd Street northward. Since a Fourth Avenue address was still not desirable for well-to-do folks, most of the residences on corner lots were constructed to face the side streets rather than the main avenue. (That all changed after 1886, when Fourth Avenue north of 42nd Street was renamed Park Avenue.)

It was in one of these corner residences of the Upper East Side that General Muff made his home.

General Muff and Miss Mary Louise Booth

General Muff has been described as “a real nobleman among cats.” It is said that the soft gray Maltese with white paws and breast was extraordinarily handsome, amiable, and uncommonly intelligent. He was also a “cat cousin” of the late John Wilkes Booth. Yes, that one.

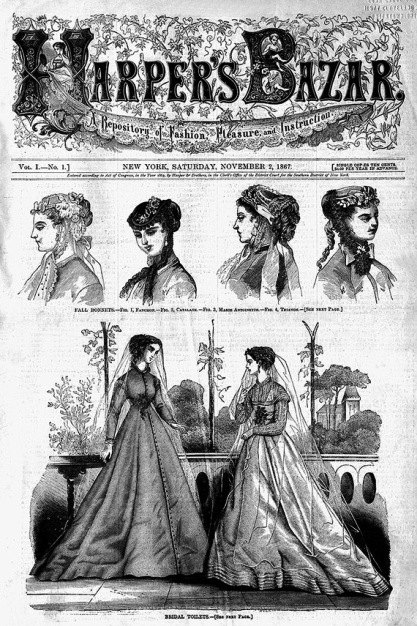

Muff was the beloved pet of Mary Louise Booth, a prominent member of New York’s literary circle who was best known for being the founding editor of Harper’s Bazar (as it was spelled until 1929). Muff lived with Mary and her best childhood friend, Mrs. Anne (Allie) W. Wright, in a three-story brownstone at 101 East 59th Street, on the northeast corner of Park Avenue.

In the 1880s, Saturday nights at Mary Booth’s Upper East Side home were legendary among New York authors, musicians, artists, statesmen, and other likewise professionals. Described as “the nearest approach to the French salon possible in America,” Mary Booth’s weekly literary gatherings were always well attended despite the remote location on East 59th Street.

Sometimes Mary’s cousin Edwin Booth would attend these events — one story described him as “a sad, gloomy man” who would stand with folded arms in the corner and talk very little to the others attending the literary meetings.

The salons took place in Mary’s parlors, which were described in The Current in 1883 as “cheerful and light in color” and decorated with items from all over the world.

There were vases from Japan, old silver from Norway, unique trinkets from Mexico and the West Indies, and even a collection of real strands of hair from the heads of Shelley, Keats, and Byron.

The pictures on her walls were all gifts from famous friends, including authors Mary Mapes Dodge and Sara Jane Lippincott, editor Whitelaw Reid, and poet Richard Watson Gilder.

Muff always figured prominently at the Saturday evening salons, donning his elaborate and expensive lace collar made in the Yucatan (a gift from writer and expeditionary photographer Madame Alice Dixon le Plongeon), and taking full responsibility for entertaining all the guests.

No Saturday evening at Miss Booth’s would be complete without his offering of a mouse during the reception in the drawing room.

Muff rarely spent much time outdoors – he was terrified of the feral cats in the backyard – but if a window was left open, he wouldn’t hesitate to take a quick romp among the backyards of 59th Street and put his superb mousing skills to work.

Inside the brownstone, he shared his little world with two canaries – Fluff and Allegretto – several red birds and mocking birds, and a little gray cat named Vashti. The cats and birds spent many hours together in Mary’s library on the second floor, which faced the backyard.

![[Park Avenue from 55th to 59th Street.] Upper East Side under development.](https://hatchingcatnyc.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/parkave55th-1.jpg)

Author Harriet Elizabeth Prescott Spofford, a dear friend of Mary’s, once wrote of Muff’s relationship with Vashti:

“His latter days were rendered miserable by a little silky, gray creature, an Angora named Vashti, who was a spark of the fire of the lower regions wrapped round in long silky fur, and who never let him alone one moment: who was full of tail-lashings and racings and leapings and fury, and of the most demonstrative love for her mistress. Once I made them collars with breastplates of tiny dangling bells, nine or ten; it excited them nearly to madness, and they flew up and down stairs like unchained lightning till the trinkets were taken off.”

From Millville to Brooklyn to the Upper East Side

Mary Louise Brown was born on April 19, 1831, in Millville (present-day Yaphank), a small hamlet in the town of Brookhaven, New York. Her father, William Chatfield Booth, had a small woolen mill and dye house, and also taught school in the winter months.

William was a descendant of Ensign John Booth, who, in 1652, reportedly purchased Shelter Island off the coast of Long Island from the Manhansett tribe for 100 yards of calico. Her mother, Nancy Monswell, was also a teacher.

Sometime around 1845, when Mary was 14, the Booth family moved to Brooklyn. There, her father opened the very first school in Williamsburg (possibly Primary School 1, which was on North 7th Street between present-day Berry Street and Bedford Avenue). Mary taught at the school for two years, but due to health issues, she stopped teaching at age 16 and devoted herself to literature.

In 1849, Mary moved to a small boarding house in Manhattan. Before taking the helm of Harper’s Bazar in 1867, she worked as a vest maker, contributed to various journals, worked as a space-rate reporter for The New York Times, and was quite active in promoting women’s rights, working alongside Susan B. Anthony and other leaders in the suffrage movement.

Mary died in her home on March 5, 1899, and was buried in the family plot in Cypress Hills Cemetery, Brooklyn. Muff died very soon thereafter. Vashti, who was also very much admired by Mary’s literary friends, was given to Miss Juliet Corson, a leader in cookery education and superintendent of the New York School of Cookery, which she founded in 1876.

“No sweeter or lovlier woman ever moved in New York literary circles.” — The Philadelphia Times, March 24, 1889.

The Booth Brownstone at 101 East 59th Street

This concludes the story of Muff, but if you enjoy history, you may want to read about the fascinating history behind the intersection of 59th Street and Park Avenue on the Upper East Side, of which Muff and Mary Booth played only a very small part.

In May 1858, real estate broker A.J. Bleecker sold a block of parcels owned by Isaac Adriance and bounded by Third and Fourth Avenue. J.C. Henderson purchased quite a few of these lots, including the lots at the intersection of 59th and Fourth Avenue. The lots remained undeveloped for about 12 years, allowing numerous squatters to take advantage of the land and establish wooden shanties there.

On May 3, 1869, at about midnight, a Croton water main on Fourth Avenue and 59th Street suddenly burst, creating a large explosion. The rushing water tore up the railroad tracks and washed away about 20 feet of 59th Street, which at the time was about 15 feet above ground level. All of the wooden shanties in the sunken lots were demolished, but miraculously, no lives were lost.

According to news reports, a shanty on the southeastern corner of Fourth and 59th was occupied by a woman and her child who had to be lifted to the roof and rescued. Jerry Curtin, a blind man, lost everything in the disaster. As the water rushed up to his chin, it was all he could do to get out of the shanty with his wife.

By the time the Croton Aqueduct Department shut the water off, it had risen to 25 feet, covering the roofs of the shanties and turning the lots into lakes. About 25 families were left homeless, all their worldly possessions scattered along the flooded streets.

Two years later, when the 1871 photo (above) of Fourth Avenue was taken, only a few shanties remained south of 59th Street. Numerous brand-new brownstones now stood where the water main explosion had taken place.

In March 1874, John Fettretch placed a classified ad for the 3-story brownstone at 101 East 59th Street. Rent was $1,700 a year or $2,000 with gas fixtures, window shades and carpets. In July 1874, Patrick Donahoe was listed as a resident, and in 1882, Mr. Stephen D. Caldwell was living at the home. Mary Booth purchased the building sometime around 1883.

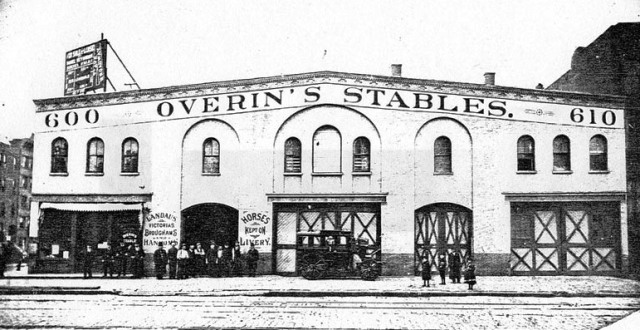

In 1891, a year after Mary’s companion, Anne Wright, died, the Booth brownstone was demolished and replaced with a five-story brick stable owned by Henry Clay Overin. The stables were one of the most popular in the city until Overin’s death in 1897.

With the advent of the motorized vehicle, the stables were converted and renamed the Mineola Garage. Several deaths are associated with this garage, including that of two-year-old Catherine Clancy, who fell four floors to the basement in a large automobile elevator shaft in 1915, and Mrs. Rose Tighe of 512 West 158th Street, who was killed in 1939 when employee Raymond Kahn lost control and drove a vehicle through a fifth-floor wall, sending an avalanche of bricks to the street below.

In 1923, Hester A. Booth of Yonkers sold the Mineola Garage and land lease to Frederick Brown. He also purchased 105 East 59th Street from Georgina McGinley and the two other brownstones shown in the photo above.

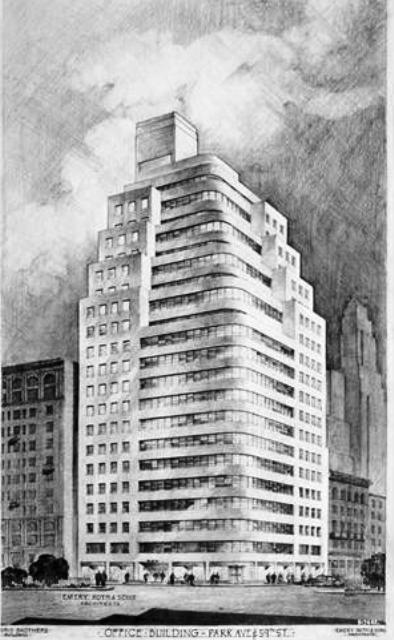

In 1924, Frederick Brown sold his property to Arthur Brisbane and M.L. Annenberg. The land was sold one last time in 1946 to Percy and Harold Uris, who put up a modern 21-story office building. According to Property Shark, in 2015 this building had a value of $78,095,000.

Should you have the chance to walk by 505 Park Avenue — or maybe attend a wine tasting there at Sherry-Lehmann — close your eyes and picture a handsome gray cat wearing a lace collar sitting in the window.