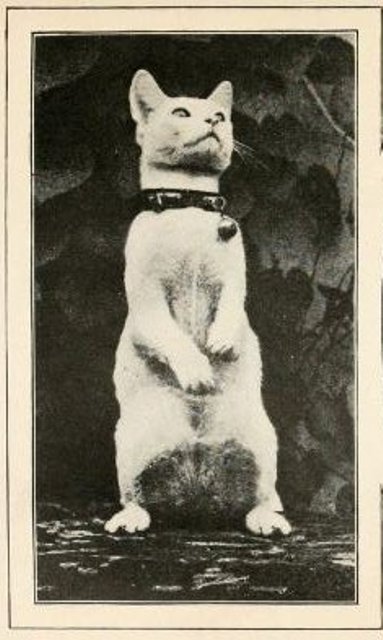

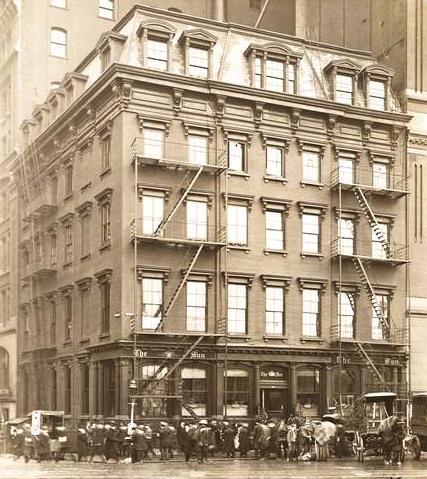

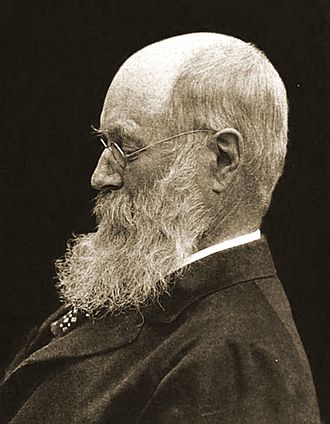

“A single member of this [cat] family has been known, on a ‘rush’ night, to devour three and a half columns of presidential possibilities, seven columns of general politics, pretty much all but the head of a large and able-bodied railroad accident, and a full page of miscellaneous news, and then claw the nether garments of the managing editor, and call attention to an appetite still in good working order.” — Charles Dana, editor of The Sun, 1868-1897

We’re all familiar with the expression, “The dog ate my homework,” and some of us may have even resorted to this excuse when we forgot or chose not to do a homework assignment.

Reportedly, the expression dates to a story in a 1905 issue of The Cambrian, a magazine for Welsh Americans, in which William ApMadoc, the journal’s music critic, relates an anecdote about a minister who once asked his clerk whether his sermon that day had been long enough. Upon being assured that it was, the minister told the clerk that his dog had eaten some of the paper it was written on just before the service.

Well, as in many affairs involving cats and dogs, the cats trump the dogs on this one — by about 20 years.

The Sun Office Cat and the Civil Service Reform Act

On July 2, 1881, President James A. Garfield was assassinated by Charles Guiteau. Mr. Guiteau reportedly killed the president because he was angry that he did not get a government position that he felt was due him. Following the assassination, President Chester Arthur pushed through legislation to put an end to civil appointments based on patronage.

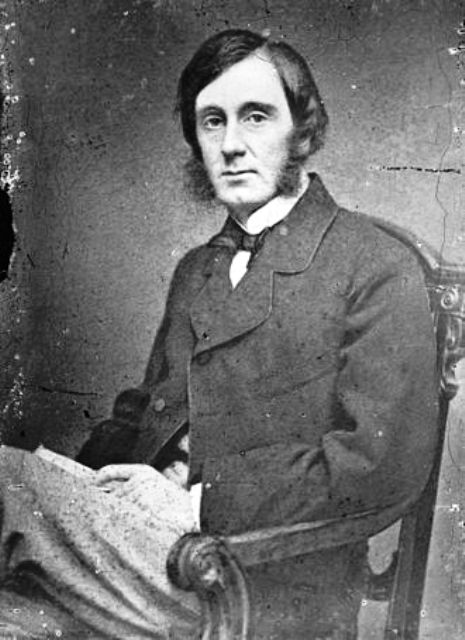

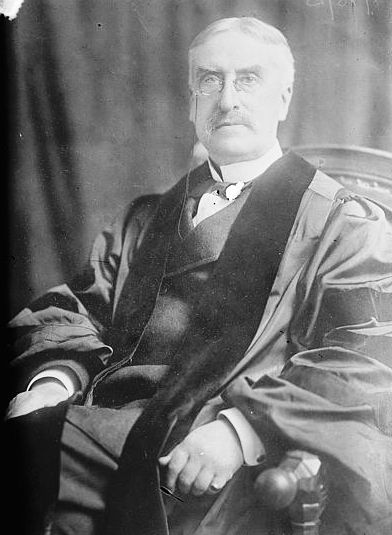

On January 16, 1883, Congress passed the Civil Service Reform Act, sometimes referred to as the Pendleton Act after U.S. Senator George Hunt Pendleton of Ohio, a primary sponsor of the legislation. The Civil Service Reform Act was written by Dorman Bridgeman Eaton, a staunch opponent of the spoils system, which awarded government jobs to party supporters, friends, and relatives.

So what does this have to do with a cat? Well, as the story goes, the cat came into play on December 30, 1884, when New York State governor and president-elect Grover Cleveland wrote a letter to George William Curtis, president of the state’s Civil Service Reform Association.

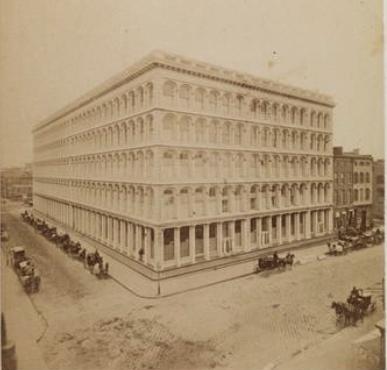

The letter, which stressed Cleveland’s intent to support the Pendleton Act during his administration, was submitted to several New York newspapers, including The Evening Post, The New York Times, and The Sun.

That Tuesday morning, the letter appeared in all the newspapers except The Sun. The “office cat” took the blame.

According to legend, shortly after the letter arrived at the desk of The Sun’s telegraph editor, it blew out an open window and was lost on Nassau Street.

When New York Supreme Court Justice Willard Bartlett inquired about the lack of publication the next day, The Sun’s editor, Charles Anderson Dana, remarked that it would be difficult to explain what happened to the readers, especially since it was well known that he was not all that fond of Grover Cleveland. Justice Bartlett responded, “Oh, say that the office cat ate it up.”

Charles Dana apparently thought this was a good idea, so he dictated a paragraph creating the cat as follows:

We are frequently obliged to deplore the circumstance that the Sun is not invariably conducted in a manner to please those of our esteemed contemporaries that do not happen to agree with us in opinion; but, sad as it is, we cannot always help it.

Here are The Evening Post and The New York Times, both seasonably exercised because the Sun happened to publish Mr. Cleveland’s letter on the civil service question on Wednesday, and not on Tuesday. The more profound of the two journals accounts for the fact on the hypothesis that we are afraid, and were “let into the astonishing journalistic blunder of trying to suppress it.”

This is a new conception worthy of its origin. The Sun is not usually suspected of being afraid of Mr. Cleveland’s publications; and we solemnly declare that, so far as we can remember, we never tried to suppress a public document that came from a President.

Since The Evening Post and The Times take interest in the conduct of the Sun, we beg to assure them that it was only through an accident that Mr. Cleveland’s letter was not published by us on Tuesday. The assistant editor, who had charge of it, lost the copy from his desk, either by some person taking it or by the wind blowing it away, or the office cat eating it up; and that is all there is of it.

In the name of the Prophet, Fudge!

The news about the cat went viral, so to speak, and within days almost every newspaper in the country had picked up on the story of the nameless office cat. In response, Charles Dana penned the following editorial about his office cat:

The universal interest which this accomplished animal has excited throughout the country is a striking refutation that genius is not honored in its own day and generation. Perhaps no other living critic has attained the popularity and vogue now enjoyed by our cat. For years he worked in silence, unknown, perhaps, beyond the limits of the office. He is a sort of Rosicrucian cat, and his motto has been “to know all and to keep himself unknown.” But he could not escape the glory his efforts deserved, and a few mornings ago he woke up, like Byron, to find himself famous.

We are glad to announce that he hasn’t been puffed up by the enthusiastic praise which comes to him from all sources. He is the same industrious, conscientious, sharp-eyed, and sharp-toothed censor of copy that he has always been, nor should we have known that he is conscious of the admiration he excites among his esteemed contemporaries of the press had we not observed him in the act of dilacerating a copy of the Graphic containing an alleged portrait of him…

We have received many requests to give a detailed account of the personal habits and peculiarities of this feline Aristarchus. His favorite food is a tariff discussion. When a big speech, full of wind and statistics, comes within his reach, he pounces upon it immediately and digests the figures at his leisure…

When a piece of stale news or a long-winded, prosy article comes into the office, his remarkable sense of smell instantly detects it, and it is impossible to keep it from him. He always assists with great interest at the opening of the office mail, and he files several hundred letters a day in his interior department. The favorite diversion of the office-boys is to make him jump for twelve-column articles on the restoration of the American merchant marine…

We don’t pretend he is perfect. We admit that he has an uncontrollable appetite for the Congressional Record. We have to keep this peculiar publication out of his reach. He will sit for hours and watch with burning eyes the iron safe in which we are obliged to shut up the Record for safe-keeping. Once in a while we let him have a number or two. He becomes uneasy without it. It is his catnip.

Many of our esteemed contemporaries are furnishing their offices with cats, but they can never hope to have the equal of The Sun’s venerable polyphage. He is a cat of genius.

Over the years, The Sun’s office cat took the blame for many news blunders. The New York Times especially liked to criticize its rival’s editorials – particularly those about politics – by suggesting the office cat must have chewed up the good parts or devoured all the copy written about any topic or candidate The Sun did not support.

Some folks took the cat way too seriously, like John J. Ford, who, while in a state of inebriation one afternoon, stormed into The Sun’s editorial room demanding to see the cat. Mr. Ford charged the cat with failing to devour an article that appeared in the Sunday paper.

Sensing that Mr. Ford did not like him, the cat howled and ran under a desk. When the man became too aggressive with the editorial staff, he was taken down by a few newspaper men and arrested by a policeman from the 26th Precinct station.

The newsmen were able to calm the office cat with a bowl of cream.

“If you see it in The Sun, it’s so.”

In 1897, Dr. Philip O’Hanlon, a coroner’s assistant on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, was asked by his then eight-year-old daughter, Virginia O’Hanlon, whether Santa Claus really existed. O’Hanlon suggested she write to The Sun, assuring her that “If you see it in The Sun, it’s so.” One of the paper’s editors, Francis Pharcellus Church, wrote the famous editorial we still celebrate today at the holiday season.

The editorial, Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus, was published on September 21, 1897. Three weeks later, on October 17, Charles Dana passed away.

Sometime shortly before his death, Charles Dana was approached by Helen M. Winslow, who was writing a book about famous cats called Concerning Cats, My Own and Some Others. (If you love cats and history, it’s a great read.)

At Ms. Winslow’s request, The Sun’s editor furnished a lengthy description of the office cats. According to Dana, the first Sun office cat was a female cat who reportedly died after drinking the contents of an ink bottle. Fortunately, she had many kittens (who were “weaned on reports from country correspondents”), and one of them advanced to the duties and honors of office cat.

Mutilator, the latest office cat at the time, was a descendant of this kitten. According to Dana, Mutilator was “a creditable specimen of his family” with “an appetite for copy unsurpassed in the annals of his race.”

I can’t say for sure that The Sun had an actual office cat or whether Mutilator really existed. For all we know, all the stories about the cat could have been made up to sell newspapers.

Helen Winslow also appears to have doubts about the story. In fact, in her introduction to Charles Dana’s text, Ms. Winslow notes, “I can only vouch for its veracity by quoting the famous phrase, “If you see it in The Sun, it is so.”

[…] Exposition. In fact, it was during this spirited competition that Charles A. Dana, editor of the New York Sun, dubbed Chicago “that windy city.” On April 25, 1890, President Benjamin Harrison […]