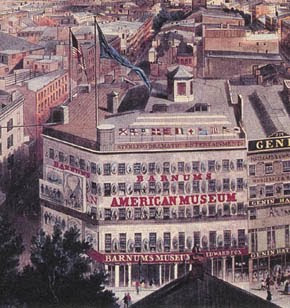

When most of us hear the name P.T. Barnum, we automatically think of the circus and “The Greatest Show on Earth.” But many years before P.T. Barnum’s Grand Traveling Museum, Menagerie, Caravan, and Circus made its debut in 1870 — and 40 years before he partnered with James A. Bailey – Phineas Taylor Barnum rose to fame with a very large collection of artificial and natural curiosities from around the world that he displayed at his American Museum in New York City.

In Part I of the American Museum story, I wrote about the history of the museum, which once stood at the southeast corner of Ann Street and Broadway. Then in Part II, I explored the fascinating history behind the land at this famous Manhattan intersection. In this final post, I write about the animals at Barnum’s museum — including the whales and the Happy Family — and the horrendous fire that took their lives in 1865.

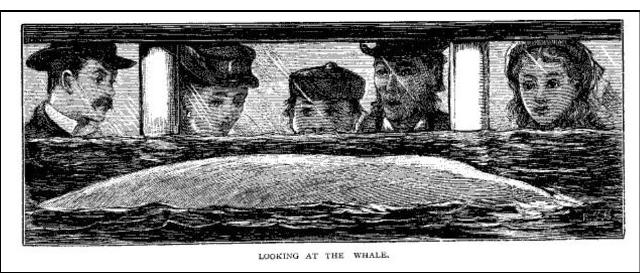

Whale Watching on Broadway

On July 1, 1861, the New York City Board of Alderman granted permission for Phineas T. Barnum to lay a six-inch cast-iron pipe from the corner of Broadway and Ann Street, down Fulton Street, under the Washington Market, and into what was then called the North River (Hudson). The work, which was supervised by the Croton Aqueduct Department, cost Mr. Barnum $7,000.

When it was completed, the pipe allowed Barnum to use a powerful steam engine to pump salt water – at the rate of 300 gallons per minute – into a large Beluga whale tank on the second floor of his American Museum.

Barnum’s original plan was to keep his live whales in a “pool” that he and his partner, Professor Henry D. Butler, built in the basement of the large five-story marble building. The first whale to use this pool was a nine-foot Beluga from Isle Aux Coudres on the St. Lawrence River in Quebec. The whale was transported to New York in a refrigerated train car and lived just nine months in captivity.

According to Professor Butler, who spoke to The New York Times in 1897 about his whaling adventures, Barnum later moved the whales to the second floor, where he installed a large 25-foot tank that he had purchased from the Boston Aquarial Gardens. All total, the American Museum spent $17,000 in 1861 in attempt to exhibit a living whale.

The Museum having expended altogether a sum not much less than $17,000 in the whaling business, this is probably the last attempt that will be made to exhibit a living whale in connection with the other expensive attractions of the Museum for only twenty-five cents. With these remarks, I leave this monster leviathan to do his own “spouting,” not doubting that the public will embrace the earliest moment (before it is forever too late) to witness the most novel and extraordinary exhibition ever offered them in this City. — P.T. Barnum, November 1861

Between 1861 and 1865, at least nine known whales were placed into captivity and put on display at the American Museum. The last two whales arrived on June 26, 1865, as was announced in The New York Times.

The Happy Family

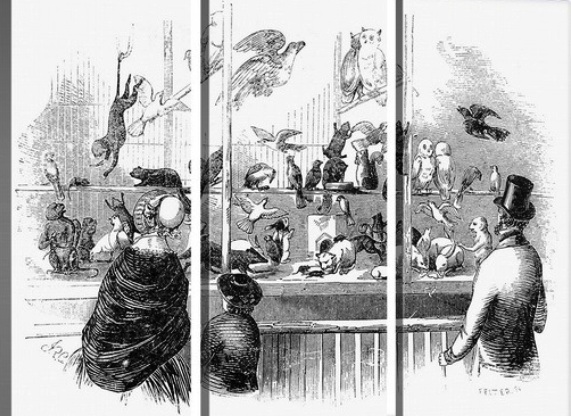

While traveling in Scotland sometime in the 1850s, P.T. Barnum visited an exhibition called The Happy Family, which featured about 200 birds and animals, including predators and prey, supposedly living in harmony in one cage. Barnum bought the exhibition and installed it in his American Museum. The Happy Family suggested that love really could conquer all, and was designed to demonstrate how so many different species could dwell together in peace and unity.

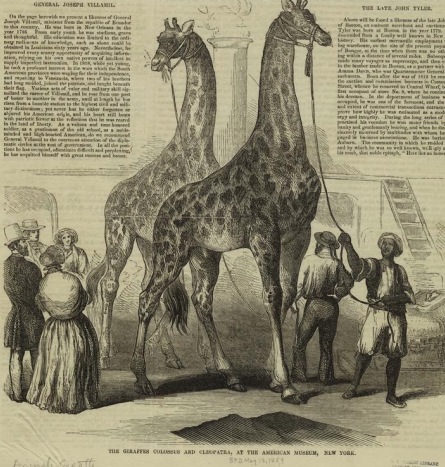

Considered one of the most interesting of the many curiosities exhibited at the museum, the Happy Family was located on the third floor, south side of the building, and consisted of a long wire cage, about 10 x 5 feet. Inside were dogs, cats, monkeys, anteaters, squirrels, mice and rats, parrots, chickens, ducks, turkeys, quails and pheasants, guinea pigs, rabbits, turtles, snakes, frogs, robins, pigeons, and more.

The Great Fire of 1865

Those animals and other creatures may have been happy, but they didn’t smell nicely; they doubtless lived respectable, but…to tell the truth, they frequently fought fiercely, and were badly beaten for it. However, they are gone; all burned to death, roasted whole, with stuffing au naturel, and in view of their lamentable end we may well say, “Peace to their ashes.” — The New York Times, July 14, 1865

On July 13, 1865, Thomas Floyd-Jones, the assistant foreman of Brooklyn’s Atlantic Hose Company No. 1, happened to be on the corner of Broadway and Maiden Lane when he saw flames shooting out from the front of the museum. Floyd-Jones later wrote about the American Museum fire in his book Backward Glances, Reminiscences of an Old New Yorker.

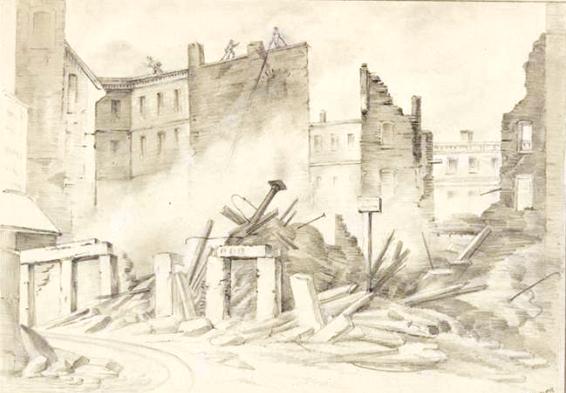

The fire had reportedly started in the basement engine room, which was used to produce the steam to pump fresh air into the Aquaria and propel the fans that kept the halls cool. By the time Mr. Tiffany, the treasurer, had run to the roof to open a large water tank, flames were bursting through the second floor and observed on the third floor near the stage. The water tank in which the whales were kept was reportedly broken in attempt to flood the floor and extinguish the fire.

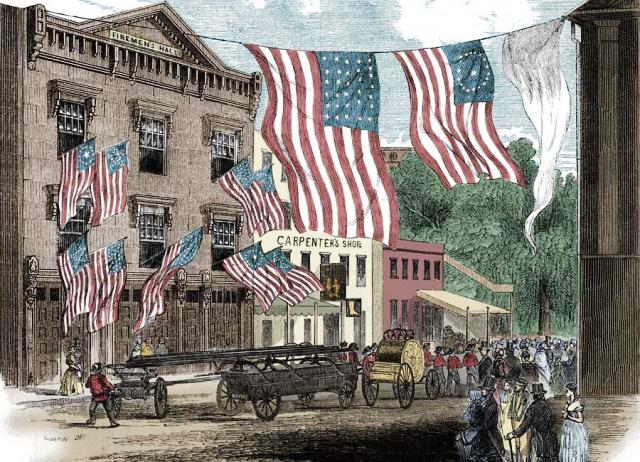

At this time, the New York Fire Department was in the process of merging into a paid system. Although many of the volunteer firemen were disgruntled, several of the old volunteer companies stepped in to help out at the fire, including a few companies from the Brooklyn Volunteer Fire Department, which responded by way of the Fulton Ferry.

The fire burned the whole front on Broadway between Ann and Fulton, including Knox’s and White’s hat stores, and destroyed all the buildings down Fulton Street, nearly reaching the New York Herald offices at Nassau Street. The fire also took the lives of all the animals in the Happy Family exhibit and all the fish and other creatures in the Aquaria, including the two new whales that had just arrived two weeks before (one whale carcass was reportedly left to rot on Broadway for several days after the conflagration).

One of the animals that was rescued from the fire was Ned, the learned seal. Ned was quite popular with the public for his ability to “play” the hand organ, and had performed for many visitors over the years, including Abraham and Mary Lincoln and their sons Robert, Todd, Willie, and Thomas (they visited in February 1860), and Joseph F. Smith, who was very impressed with Ned when he saw him in July 1863.

According to Thomas Floyd-Jones, Ned was saved by Clifford C. Pearson, a member of the Atlantic Hose Co. No 1. Pearson reportedly took the seal under his arm, placed him in a basket, and pulled him by cart to the Fulton Street Market, where he placed him in Alfred P. Dorlon’s fish trough.

In addition to Ned the seal, two bears also reportedly survived the fire. Samson, a grizzly bear, had been removed just before the fire began, and another large bear was reportedly lowered down from a fire escape by a chain. Some news reports tell of of a polar bear that escaped and walked down the street to the Custom House (where it then fell from a balcony and broke its neck), and of animals jumping from windows to escape the flames.

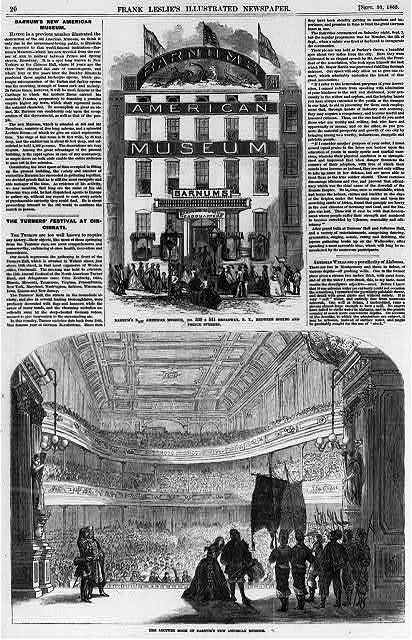

Barnum’s New American Museum at 539-541 Broadway

Not easily defeated, Barnum quickly picked up the pieces and began looking for new curiosities to replace those he lost in order to fill his new museum at the old Chinese Museum building at 539-541 Broadway, between Prince and Spring streets.

As the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported on July 15, 1865:

“He is already in negotiation with the leaders of the Republican party, who are expected to be a welcome substitute for the Happy Family. The man who tamed that cat so that it took the rat to its embrace, is confident that he can keep the discordant leaders of the Republican ranks quiet in the same cage.”

Maybe today’s Republican Party would be open to a similar suggestion…

In addition to setting up shop at a new location, Barnum was also able to quickly sell his land lease for $200,000 to James Gordon Bennett, who bought the property from Olmstead for $500,000. Out of the ashes of the old museum then arose the new marble building of The New York Herald.

In May 1895, the New York Herald building was razed to make way for a skyscraper built by Henry Osborne Havermeyer, the president of the Sugar Trust, who had reportedly purchased the property for about $900,000. Called the St. Paul building, the skyscraper stood at the corner of Broadway and Ann Street from 1899 until 1958, when it too was razed in the name of progress to make way for the Wester Electric Building, which still stands today at 222 Broadway.

Incidentally, P.T. Barnum’s New American Museum was destroyed by fire in 1868. I’ll save that for another story some other time.