“His collection of tabbies is the only show made up entirely of feline soubrettes that was ever organized in the world. Everything they do is performed with the upmost grace. They are as clever as any trick dogs or monkeys and much more entertaining to watch.” – Los Angeles Herald, September 6, 1896, in a feature story about George Techow

A Vagrant Catch is the Easiest to Teach

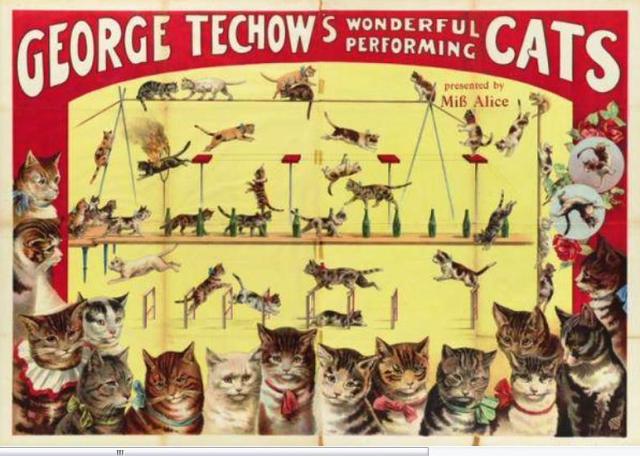

In the winter of 1895, about 18 trained cats dubbed “the latest sensation in European music halls” by the Philadelphia Times in October of that year made their New York City debut at Oscar Hammerstein’s Olympia Theatre Music Hall on Broadway.

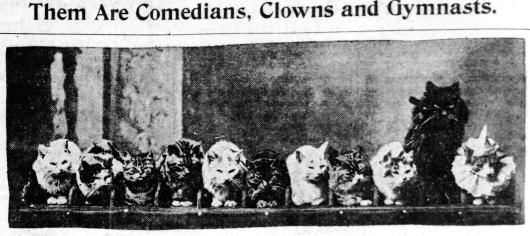

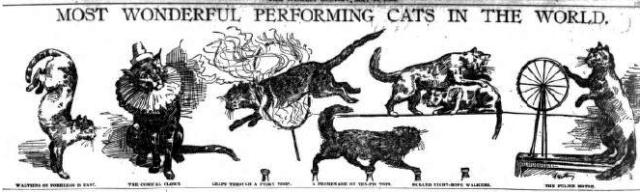

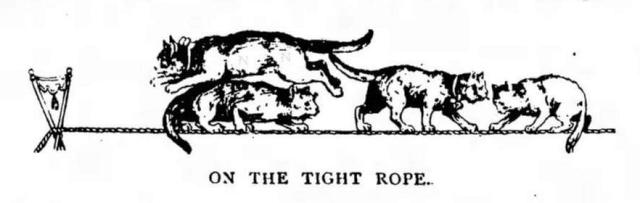

Under the care of trainer Herr Professor George Techow of Hamburg, Germany, these performing felines could walk on their front feet, jump through hoops of fire, jump over each other on a tightrope, and perform other acts that astonished vaudeville audiences.

Herr Techow had been working as an animal trainer at Hagenbach, Germany, when it occurred him that the first person to successfully train cats to perform would be a big hit. He also realized it would take an immense amount of time and patience, but he was determined to give it a try.

Angora and Persian cats were all the rage at this time, so Techow got 10 of the prettiest Angoras he could find. He tried, for over a year, to teach them a few simple tricks, without success. As Techow often told the press – and as was later recalled in the book Concerning Cats: My Own and Some Others — the Angora cats had been bred simply for their good looks. They were lazy, he said, and as a result of inbreeding and generations living with rich folk, they had become “stupid and inert.”

“Only one of the 10 showed any intelligence,” Herr Techow said. “I realized I’d have to use cats from the streets, ownerless felines.” He explained that he “picked street cats that had a bad reputation in the quarter where they prowled, cats that were adept at stealing food from kitchens and butcher shops, for I knew these were unusually intelligent.

“A vagrant cat is the easiest to teach, the quickest to learn,” George Techow explained. “Just as a street gamin gets his wits sharpened by his vagrant life, the stray, half-starved cat, forced to defend himself from foes and to snatch his living where he can, has his perceptive faculties quickened and his brain-cells enlarged.”

Herr Techow was always quick to point out that he never whipped his cats (although he sometimes tapped a whip on the ground as a signal), because fear and punishment do not work with cats. They simply do not understand the purpose of punishment, and, as he told the press, a cat never forgets a blow, nor licks the boot that has kicked him. Although the cats would often misbehave as cats are wan to do, once they got on stage they were all business.

“It can take years to train a cat,” George Techow told The New York Times in 1903. “I can train 12 dogs to perform a number of tricks in the same time it takes to train one cat to perform the simplest act.”

According to Helen Maria Winslow, author of the aforementioned book, the cats were quite fond of their trainer, and would welcome him into a room with purrs and meows. Each cat had a little wire cage for traveling filled with a layer of hay and sawdust, and when George Techow opened the cages, the cats would scramble all over him. (At home they slept in an enormous wicker basket with eight compartments. While on stage, the cats occupied little compartments or tables while awaiting their turn to perform.)

Herr Techow and His Trained Cats Wow New York City Audiences

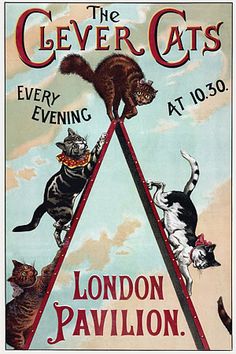

Following their European tour, including some performances at the Empire Theatre and London Pavilion in London, Herr Techow’s trained cats came to America to wow audiences in cities like Boston, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Philadelphia, and New York. The cat’s first tour took place in 1895, but according to news reports, it looks like they came back a few times in 1902 and 1905.

As the Morning Telegraph reported on April 6, 1905:

It is usually considered that the cat, while a useful as well as ornamental feature in domestic life, is rather difficult to train, but George Techow has succeeded in bringing fifteen or twenty of these midnight prowlers to a point where they are really cultured animals and capable of furnishing no end of amusement. To be sure, many of the feats partake of the usual stunts on the back fence, but they are quite cultivated in spite of that and show the care taken in their education.

In October 1895, the performing cats took the stage for the first time in New York City at Oscar Hammerstein’s Olympia Theatre Music Hall on Broadway.

One of the stars of the show was Muller, the clown cat, who always brought down the house with his antics. Muller wore a hat and a “Judy collar,” and would run circles around his feline co-stars in the way a circus clown would run around the elephants to get a few laughs.

Other stars of the show included Fuchs, a ginger cat from Switzerland who could box with his master or turn a spinning wheel (when he had enough of spinning the wheel, he’d scratch Herr Techow as if so say, “I’ve had enough”).

Peter and Paul from Saxony performed on a trapeze, and other cats like Angot, a white cat from Paris, Bossy, Max (angry but clever) Mietze, and Muller’s son, took part in other various stunts.

Cat on a Cool Roof at the Olympia Theatre

In the summer of 1886, Herr Techow’s cats were invited to perform at Oscar Hammerstein’s Olympia Theatre roof garden. At 44th and Broadway, the Olympia Theatre took up an entire city block and was covered with a 65-foot high frosted-glass roof.

The roof garden was lit with 3,000 electric lights (this illumination initiated a trend that would transform the emerging theater district into the Great White Way), and water pumped from a refrigerated tank in the basement flowed through pipes in the roof to keep it cool.

The cats must have been very tempted to break free from their performance and explore the roof’s rustic alpine features. The roof featured rock crags and a stream that flowed into a 40-foot-long lake.

Not unlike Hammerstein’s “Dutch farm” atop his Paradise Roof Garden at 42nd Street and 7th Avenue, the roof garden at the Olympia had live swans imported from Russia, South American monkeys, a duck pond, little cabins, gardens, and a wooden bridge. There was also a promenade around the building that provided views of New Jersey and beyond Central Park.

Unfortunately, the giant theater complex proved a quick failure and bankrupted Oscar Hammerstein (although he quickly re-established himself at the aforementioned theater on 42nd Street). On June 29, 1898, the debt-laden Olympia was auctioned off to new owners, who remodeled the Olympia into three theaters:

The 2,800-seat Olympia Music Hall was reduced to a 1,675-seat playhouse called the New York Theatre. The Olympia’s other playhouse, the 1,700-seat Lyric, was reduced to about 900 seats and renamed the Criterion, and the roof garden was enclosed into a conventional 925-seat theater called Jardin de Paris.

For a brief time the New York Theatre operated as the Moulin Rouge (1912), but it reverted to the New York Theatre a year later. In 1915, a young Marcus Loew took over the New York Theatre and the roof theater, and converted them into movie cinemas. Admission prices were the lowest on Broadway – just 10 or 15 cents depending on time of day.

In 1935, the buildings were demolished to make way for a new cinema built by B.S. Moss called the Criterion, plus retail stores and a dance hall called the International Casino nightclub (historians are unclear as to whether some or all buildings in the complex were demolished and rebuilt, or the shells were gutted and remodeled). The 1,700-seat Criterion Theatre opened in September 1936 and was later leased to Loew’s for about 20 years.

In March 1980, the Criterion Theatre was converted into five large movie screens. The theater — named the Criterion Center Stage Right in 1988 — continued to operate in the seedy Times Square district until the spring of 2000, when it was gutted to become the massive Toys R Us flagship store with 60-foot Ferris wheel.

Sadly, the toy store and the giant Ferris wheel were recently replaced by an Old Navy and Gap store.

As for Herr Techow’s cats, they went on to continue performing with George’s daughter, Alice, until about 1925.

Street cats are indeed very smart. We moved one from our neighborhood which was several miles away due to it kept knocking ours around when she was outdoors. He found his way back. He has since met his demise. (But not by us)

[…] Source: 1895: Muller, the German Clown Cat That Brought Down the House in New York City […]