In my last post, I introduced you to Morgan Phillips, an old circus man who lived in a tent at 40 Cherry Street in New York City with his wife, their grandson, a horse, and some dogs. In this post, I’ll tell you the beginning and the end of Morgan’s story, and explore the history of 40 Cherry Street.

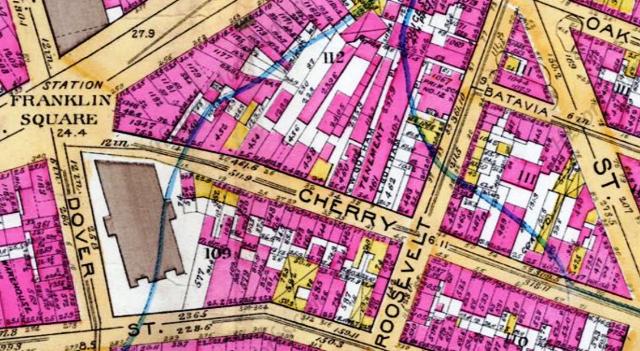

Morgan and Clarissa S. Phillips lived at 40 Cherry Street — the white rectangular lot south of Roosevelt Street in this 1891 atlas of Manhattan. Just to the left is the massive Gotham Court Tenement, constructed in 1850. The long, narrow alleyways West Gotham Place and East Gotham Place are on either side.

Morgan and Clarissa S. Phillips lived at 40 Cherry Street — the white rectangular lot south of Roosevelt Street in this 1891 atlas of Manhattan. Just to the left is the massive Gotham Court Tenement, constructed in 1850. The long, narrow alleyways West Gotham Place and East Gotham Place are on either side.

The Beginning of the End

On August 22, 1892, a young man was found lying in the street at the corner of Market Street and East Broadway. According to news reports, he was taken to Gouverneur Hospital, where, just before he died, he said his name was Albert and that he lived at 30 Monroe Street. Shortly thereafter, an unidentified elderly man called at the hospital and said the young man was his son, Albert Phillips.

This elderly man was no doubt Morgan L. Phillips.

On Wednesday, June 7, 1893, less than a year after their son’s death, Morgan Phillips and his wife, Clarissa, moved their small red-striped canvas tent from the vacant lot at 30 Monroe Street to the fenced-in lot at 40 Cherry Street.

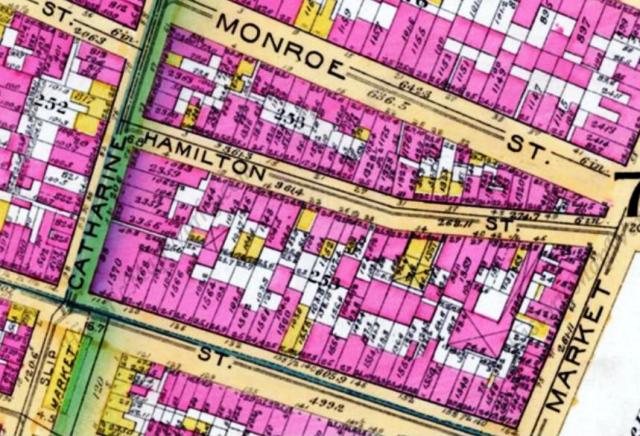

The Phillips were living in a tent in a vacant lot at 30 Monroe Street (the white lot just above the bend in Hamilton Street) when Albert died in August 1892. Today, this square block between Cherry, Market, Catherine, and Monroe streets is the site of the Knickerbocker Village housing development, erected in 1933-34.

The Phillips were living in a tent in a vacant lot at 30 Monroe Street (the white lot just above the bend in Hamilton Street) when Albert died in August 1892. Today, this square block between Cherry, Market, Catherine, and Monroe streets is the site of the Knickerbocker Village housing development, erected in 1933-34.

According to an article in the New York Herald on June 12, 1893, the family had been living rent-free at 30 Monroe Street for quite a few years when they were forced to find a new home. Apparently, one of the heirs of the estate passed away, and the surviving property owners wanted to erect a four-story tenement on the small lot.

Although they reportedly had several grown children who begged them to find a real home, Morgan and Clarissa moved to 40 Cherry Street, where their tent served as a parlor and dining room, and an old Tally-Ho stagecoach served as their bedroom. Two “large, fierce dogs” and a big bay horse shared the lot with the couple and their grandson (possibly one of Albert’s two sons).

In 1934, when this photograph was taken, 30 Monroe Street was once again an empty lot, so to speak; the four-story tenement built in 1893 had already been demolished to make way for the new Knickerbocker Village under construction. NYPL Digital Collections

In 1934, when this photograph was taken, 30 Monroe Street was once again an empty lot, so to speak; the four-story tenement built in 1893 had already been demolished to make way for the new Knickerbocker Village under construction. NYPL Digital Collections

The Passing of Clarissa

In the fall of 1893, 76-year-old Clarissa visited a daughter who lived in Seneca Falls, New York. Shortly after returning to New York City in January, she developed pneumonia. Since she was not fit to sleep outdoors, the couple rented two squalid back rooms on the third floor of a four-story pre-Old Law tenement building at 33 Cherry Street.

On February 13, 1894, Morgan Phillips said goodbye to his wife of over 40 years. Heartbroken and confused, Morgan failed to call for an undertaker. Neighbors who had heard Clarissa groaning, and who had seen Morgan kneeling next to her motionless body in the bedroom through a common hallway window, thought he had killed her and called for the police.

Clarissa Phillips died at 33 Cherry Street, seen from the back in this photo taken from Water Street in 1936 (farthest windows on right). When the block was demolished as part of a slum clearance project, it was discovered that No. 29-29½, the squat, 2-story building in the shadows, was an old Dutch-style townhouse that once housed the officers of George Washington’s staff. Efforts to save “the oldest house left in Manhattan” were unsuccessful. NYPL Digital Collections

Clarissa Phillips died at 33 Cherry Street, seen from the back in this photo taken from Water Street in 1936 (farthest windows on right). When the block was demolished as part of a slum clearance project, it was discovered that No. 29-29½, the squat, 2-story building in the shadows, was an old Dutch-style townhouse that once housed the officers of George Washington’s staff. Efforts to save “the oldest house left in Manhattan” were unsuccessful. NYPL Digital Collections

When Policeman O’Connor, Roundsman Wilbur, and Officer Bowen of the Oak Street police station arrived at the apartment, they had to force open the door. Morgan Phillips told them he did not answer the door because he was frightened and thought he might be harmed. He explained what had happened to his wife and then told them the story of his life.

On February 14, Morgan got a burial permit from the Board of Health. Many neighbors attended her funeral services the next day.

When Policeman O’Connor came to check on Morgan’s welfare after the funeral – to make sure that he hadn’t froze to death – Morgan Phillips was wrapped in blankets and surrounded by straw. He said he could not bear going back to the apartment where his wife had died. Policeman O’Connor said there was no law against sleeping in the open air, so he let him be.

Officer Alonzo S. Evans of the SPCA also came out to check on him and found that the horse and dogs were fine. Officer Evans reported that the tent afforded good protection from the weather for both man and beast, although the roof leaked a little.

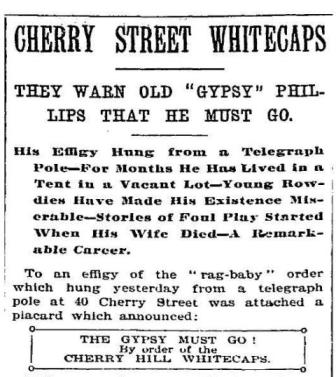

The Final Straw on Cherry Street

On March 7, 1894, three days after the Cherry Hill boys hung an effigy from a telepgraph pole on his lot, Morgan Phillips died at Bellvue Hospital at the age of 76 (give or take a year). The New York press said he died from pneumonia. We all know that he died of a broken heart.

A Brief History of 40 Cherry Street

This concludes the story of Morgan Phillips. (I regret that I do not know what became of the grandson, the horse, or the dogs.) If you like to explore New York City history, you may enjoy the following about Cherry Street.

In the late 1600s, Cherry Street was a small roadway along the shores of the East River that led to Mayor Thomas Delavall’s cherry orchard located on a hill just behind a marsh. This marsh–later called Franklin Square–was the source of the Ould Kill creek, which flowed into the East River. The marsh and creek were later covered over to construct Roosevelt, Dover, and other streets in the city’s Two Bridges neighborhood.

In this John Montresor map of 1766, Cherry Street is the small roadway running along the river; Love Lane is today’s East Broadway; the Road to Crown Point, which bisected the Delancey estate, is today’s Grand Street; the Rope Walk, where material was laid out and twisted into rope for ships, is now Division Street; the Henry Rutgers Farm (right), is now the Rutgers Houses public housing development between Pike and Rutgers Street; and the marshy area at bottom left is the approximate site of old Franklin Square, seen in the 1891 map above.

In 1672, the heirs of Dutch settler Govert Loockerman sold at auction a seven-acre parcel of land near the foot of present-day Roosevelt Street (where Egbert Van Boerum built the city’s first ferry house in 1656) to ship captain Thomas Delavall for 160 guilders (about $50). Thomas in turn sold the land to Elias Puddington, a ship carpenter, who then conveyed the land to John Payne, a Boston ship captain.

By 1700, the land was in the hands of John Latham, a British shipwright who established a large shipyard at the foot of Roosevelt Street.

Famous Cherry Street Residents

In 1770, Walter Franklin, a merchant, built his house at 1 Cherry Street (corner of Franklin Square and Cherry Street). This house was later occupied as the first presidential mansion by George Washington from April 23, 1789, to February 23, 1790, during New York City’s two-year term as the national capital. The house was demolished around 1850 to widen the street. A bronze plaque where Pearl Street crosses under the Brooklyn Bridge approach marks its location.

Samuel Chester Reid, an officer in the United States Army during the War of 1812, was living at 27 Cherry Street when he designed the present pattern of the American flag of stars and bars. Other famous Cherry Street residents include William “Boss” Tweed (born at No. 24), John Hancock (No. 5), and Samuel Leggett, founder of the New York Gas Light Company (now Con Ed), whose home at No. 7 Cherry Street was the first in New York to be illuminated by gas.

The Latham Mansion at 40-44 Cherry Street

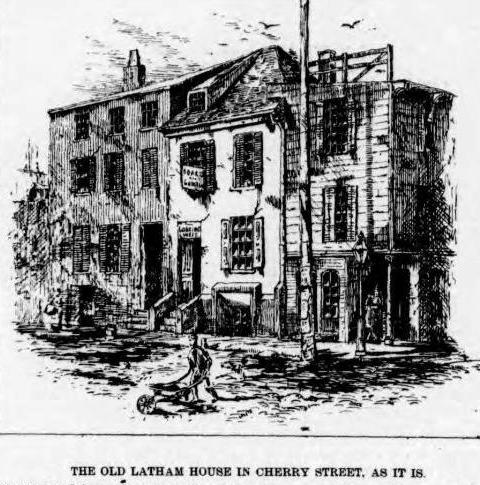

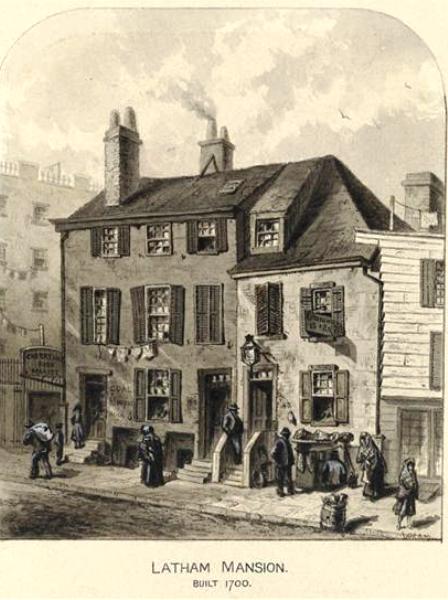

In 1720, John Latham built a large mansion on the southwest corner of Cherry and Roosevelt. It was numbered 40,42,44 Cherry Street. Back then, before landfill was added to create South, Water, and Front streets, the home was only 100 feet from the East River. Family members continued to occupy the house until 1809, just nine years after son Daniel Latham died in the home at the age of 95 or so.

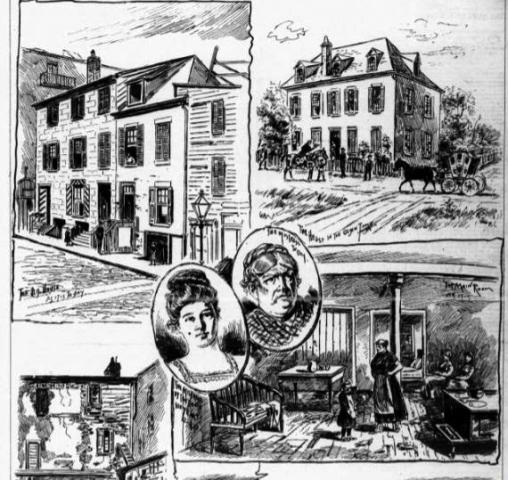

On November 18, 1874, The Daily Graphic published a story about the Latham house in which the original house (pictured above) was compared to the structure as it was on that date (pictured below). According to the article, the high-pitched pointed roof, the long gable window, and door sills were unaltered, but a floor or more had been added to the corner house (No. 44) and a parallel stoop had been replaced with a more modern stoop. In 1874, No. 40 and 42 was a boarding house and the corner house was a drinking saloon.

Following Daniel Latham’s death, the Latham estate had numerous owners, including Charles Stonehouse, who purchased the property from Stephen Latham in 1813, Archibald Kerley (a prominent member of the city’s early volunteer fire department), and Charles Lorton. In 1816, Lorton’s neighbor at 38 Cherry Street was a guy named Flamin Ball (how often does one get to write “Flamin Ball” in a serious piece?)

In the 1820s and 30s, James P. Allaire operated a foundry at 40 Cherry Street, where he built marine engines and boilers. In the late 1830s, 40 Cherry Street was occupied by William King, a London silver polisher.

In this 1878 illustration of the Latham Mansion, you can see the large Gotham Court tenement building on the left. Around this time, 40 Cherry Street was occupied by residents on the top floors, a barber shop on the ground floor, and a wood-wares shop in the basement. Museum of the City of New York Collections

On January 6, 1883, as reported in the New York Herald, a city building inspector ordered the old Latham house be torn down. According to his report, the floors were warped and the building was in an otherwise very dangerous condition.

The building inspector’s report was obviously ignored in 1883, because on October 2, 1888, The Daily Graphic took another look at the Latham house as it was in the 1700s and on that date. Sometime between 1888 and 1890, when Smith Ely purchased the lot at 40 Cherry Street, the house was finally demolished.

In 1786, Joseph Latham constructed a townhouse at No. 41 Cherry Street. In the late 1890s and early 1900s, an African-American by the name of Mr. Young operated a boarding house here for “Negroes who follow the sea.” In 1902, the Irish and Italian neighbors reportedly stopped fighting each other to celebrate in the streets when Mr. Young was charged with arson following a fire at the house. The building was still standing in 1914, when this picture was published in a book of historic buildings by the Bank of the Manhattan Company.

On July 23, 1895, a sewer between the Gotham Court tenement building and the vacant lot at 40 Cherry Street caved in, sending three young boys into the drain (they were all rescued). According to the news report, the lot where Morgan Phillips once lived was being prepared for the construction of a new molding factory. The side wall of the sewer gave way as the excavators were digging a cellar in the lot for the six-story building.

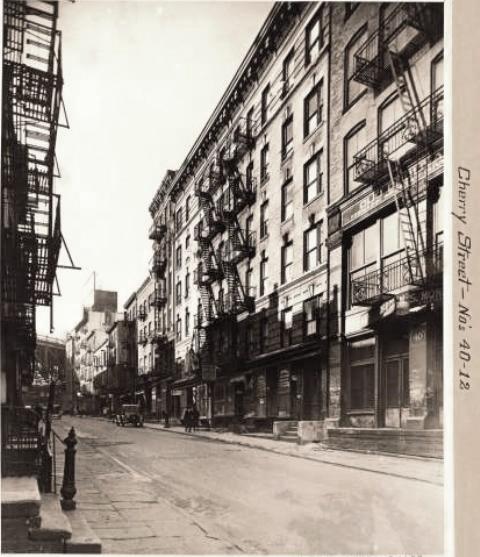

In 1925, 40 Cherry Street (far right) was occupied by N.S. Monahos & Co. (importers) and apartments on the top floors. The Gotham Court tenement had been long gone at this point; it was was demolished in 1895 under the Tenement House Law and replaced by the New Law tenements seen here. NYPL Digital Collections

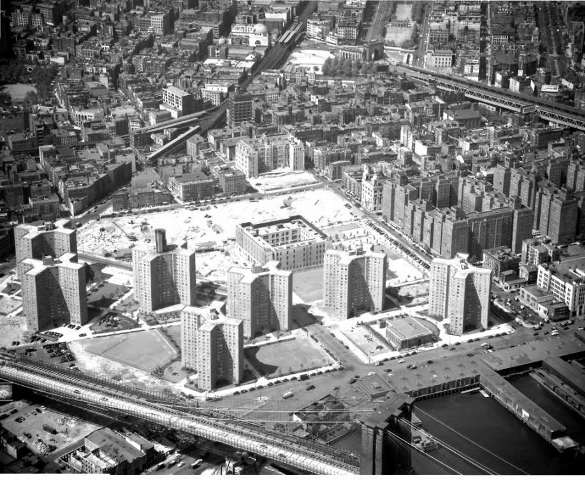

In March 1934, the newly-formed New York City Housing Authority kicked off its citywide slum clearance campaign. Buildings on Cherry, Madison, Roosevelt, Oak, and other old streets in the Two Bridges neighborhood were razed over the years to make way for large public housing developments like Knickerbocker Village and the Governor Albert E. Smith Houses.

[…] Part II of this old New York tale, I’ll share the sad conclusion to this story and explore the fascinating history of 40 Cherry […]

I, too, do not know what became of the horse or the dogs, but I do know what became of Morgan’s grandson. He was my grandfather. Thank you for putting some “meat” on Morgan’s genealogical bones. A few of the details presented in your article are not quite right, but I’m guessing Morgan was one who liked to embellish a story.

I notice there is no mention of Albert’s 3 older sisters who were shipped off to their mom’s cousins in Michigan between Aug 1 and Aug 22, 1850, where they remained or the rest of their lives.

How fascinating! I love connecting with relatives of the people in my stories, so thank you for writing. All of my stories are based on old news articles–I have found that oftentimes it was the reporter who embellished a story, so we’ll never know if it was Morgan or the reporter who told a different story than the actual facts. What did become of his grandson, besides obviously marrying and having a family? Did he stay in New York? I did not know about his older sisters — there was no mention of them in the news articles and of course they wouldn’t have been listed in the 1855 census report that I found. Thank you for sharing.

Fred married Mabel Saynor who he met on a trip to Michigan to visit with his father’s sisters. His mother, Emma Johnson Phillips, remarried after the death of Albert. Her new husband had an active barge business based out of Elmira, NY. Fred went to work for his stepfather running a grain barge on the Erie Canal for several years. With the onset of young children, there was concern about so many children on the boat and their education. He and his growing family moved to Syracuse where he became a tool & die maker/machinist for Crouse-Heinz. He died in 1944 leaving Mabel, 8 children and many grandchildren.

Fred’s aunts show up in both the 1850 NYC Federal census and the Michigan census which is why I was able to narrow down so closely when they were sent to Michigan. Albert was born after they went to Michigan.

This is great information. When I get a chance, I will add Fred’s named to the story.

I went to Syracuse University — one of my favorite building on campus was the Crouse College building. And I visited the Erie Canal Museum several times while I there. Thank you again for filling in the missing ending.

My mom graduated from Syracuse!