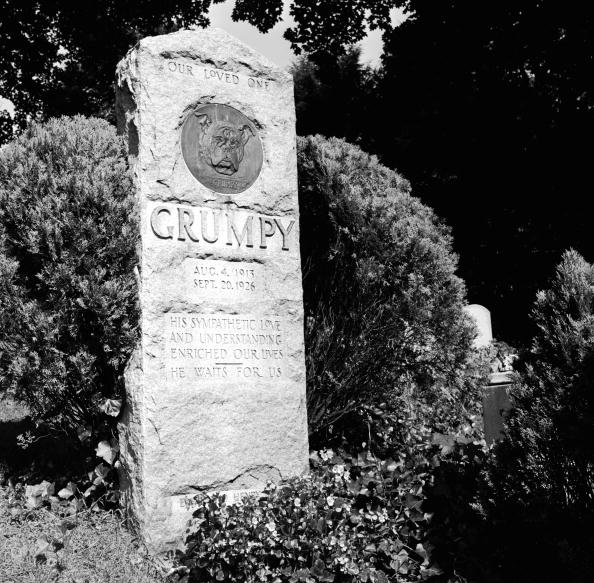

I recently made my annual pilgrimage to the Hartsdale Pet Cemetery in Westchester County, New York, to spend some time with Grumpy. The Hartsdale Pet Cemetery is rich in animal tales and history, which is why I love spending a few hours there to see what stories of Old New York are waiting to be unearthed, so to speak.

Each pet monument is a treasure in its own way, but there are always a few that catch my fancy on every visit. As I’m always drawn to Grumpy Bizallion, I thought it time to explore the story of this beloved bulldog.

For years, Grumpy’s monument was the tallest at Hartsdale Pet Cemetery, standing just over six feet. Unfortunately, the foundation weakened over the years, putting the stone at risk of tipping over. For safety reasons, the cemetery cut the Grumpy monument into two pieces.

According to the monument, Grumpy was born on August 4, 1913, and died on September 20, 1926. We also know that his pet parents were Emma and Henry Bizallion, and that they loved him very much. Underneath the bronze relief bearing Grumpy’s likeness is carved, “His sympathetic love and understanding enriched our lives. He waits for us.”

But who were Emma and Henry Bizallion, and what is their story? Why was this bulldog named Grump so important to them – even though he was presumably a grump?

Henry H. Bizallion and Emma Loriett Coy

Henry Herbert Bizallion, the first of three sons born to Eugene Bizallion and Martha A. Seaver, entered the world on May 17, 1870, in a small town in Rutland County, Vermont. His father, a Canadian, excelled as a wood cutter when this skill was in great demand during the construction of the railroads, and then later worked as a cheese maker in Middletown Springs, Vermont.

Henry graduated from Saint Johnsbury Academy, and on June 13, 1893, he married Emma Loriett Coy, the daughter of Martin Coy and Susan Greene of Middletown, Vermont. At some point between their marriage and 1900, the Bizallions moved to New York City, where Henry worked in the banking industry.

From 1900 to 1910, Henry Bizallion moved quickly up the banking corporate ladder.

In 1900, while living with Emma at 32 Hamilton Terrace in the Hamilton Heights section of New York, Henry was working as an assistant cashier at the Riverside Bank on Eighth Avenue near Columbus Circle. Five years later, they were living closer to the bank at the new Hotel Lucerne, an upscale residential hotel at 201 West 79th Street constructed in 1903. By 1908, the year that Riverside Bank merged with the Hamilton Bank and the Northern Bank of New York, Henry was a full-fledged cashier (an officer position) as well as a director of the bank.

Just prior to the merger, Henry resigned from the Riverside Bank. He and a few banking friends collected $200,000 and formed the new Gotham National Bank organization, to accommodate the new automobile trade. They rented the store and basement occupying the Eighth Avenue front of William R. Hearst’s New York American Building at Columbus Circle, and in April 1910, Henry was named president of new The Gotham National Bank of New York.

By this time, the Bizallions were living in one of the four-story brick apartments at 229-235 East 105th Street in East Harlem. Although they had been married for 17 years, they had no children. I’m not sure what Emma did to pass the time, but Henry kept busy with the bank as well as with his positions as an officer of the Central Park West and Columbia Avenue Association and the director of the Broadway Association.

The Dog Lovers’ Protective Association of America

According to published court reports, the Bizallions left their apartment in New York City and moved to Summit, New Jersey, sometime around 1912. It was here in the suburbs that they adopted a bulldog puppy named Grumpy.

Two years later, in 1914, Henry Bizallion joined Ellin Prince Speyer, Mrs. Vernon Castle, James Gardner Rossman, and several other notable New York and New Jersey dog lovers in forming the Dog Lovers’ Protective Association of America (DLPAA).

The DLPAA, created in response to a dog-phobic atmosphere, was primarily for the owners of “jes’ dogs” – in other words, ordinary canines that were not bred or considered to be pedigrees. It’s not that Henry and the over 100 other members frowned upon dog aristocracy; they just preferred to promote “ordinary, plain, everyday dogs” like Grumpy. (In fact, Agnes Rose Rossman, secretary and wife of association president James Gardner Rossman, raised Maltese terriers and had won “Best in Show” at the Westminster Dog Show.)

The DLPAA also advocated for a special show for dog heroes – thoroughbred or mongrel — in response to pending legislation to address the large number of dogs running at large in New York City. Apparently, New York Board of Health Commissioner Sigismund Schulz Goldwater was trying to terrify the public regarding the menace of the dog, and wanted to make New York a dogless city.

Here’s a snippet of what Dr. S.S. Goldwater wrote in the January 1915 edition of the American Journal of Veterinary Medicine:

“The dog must go. He must go where he belongs to his proper place — to the country. Assuredly I favor the exile of all dogs from Manhattan Island. I hope to see New York City a dogless town.”

He went on to say that although he was fond of dogs, “In a policed community, the pet dog is superfluous. No true lover of dogs will bring a dog into the wretched and unhappy surroundings of city life.” (Dr. Goldwater also wanted to ban all cars from the city, but that’s another story for another blog.)

In response to Goldwater, DLPAA president James Gardner Rossman wrote:

“Not until the emotions of love, courage, faithfulness, devotion, [and] companionship can be legislated out of the heart of man will man tolerate without resistance legislation which is simply persecution of his dumb companion and most faithful friend the dog.”

Obviously, this crazy proposal to ban all dogs from the city went down with the S.S. Goldwater ship, so to speak.

The Wicks-Brown Dog Licensing Bill

In the summer of 1916, New York Senator Charles Wells Wicks proposed new legislation titled “An Act of Encouraging the Sheep Industry.” The law was reportedly designed to help New York sheep farmers by protecting them from the alleged ravages of dogs roaming at large.

Often called the Wicks Law or Wicks-Brown Dog License Law, the law required dog owners to pay a $3.25 licensing fee for females and $2.25 for male dogs. Owners of dogs captured at large would have to pay a $10 pound release fee. Supposedly, monies collected from these fees would be used to help farmers purchase new sheep to replace those killed by dogs.

The Wicks Dog Law also required that all peace officers kill dogs seen attacking or chasing sheep, fowl, or other domesticated animals (cats and other dogs), or when seen just roaming at large beyond its owner’s premises without wearing a mandated license tag (the officers would first have to make a reasonable effort to secure the dog and fail). In fact, anyone could kill, without recourse of law, any such dog committing these acts.

Many prominent people, including William O. Stillman, President of the American Humane Association, were openly opposed to the bill. Even some sheep farmers thought it was shear madness. As opponents noted, the bill offended nearly 200,000 dog owners in New York State in order to please a few hundred sheep owners who were hurt, not so much by roaming dogs, but by cheap Western grazing lands and foreign competition.

S.O.S. for Dogs in New York City

Although Wicks Law did not apply to New York City and other large cities in the state, it would affect those dogs whose families took them to places like Long Island, Westchester County, or other counties beyond Manhattan. If a city dog such as Grumpy got loose in the country, he could be shot, simple as that.

Henry H. Bizallion and his friends at the Dog Lovers’ Protective Association of America called the Wicks Law “the most vicious dog legislation that has ever been attempted in the United States.” In response to the bill’s passage in the New York Senate (by a vote of 31 to 14), they filed a petition with Governor Charles S. Whitman in May 1917, asking him not to sign the bill into law. The title of their petition was S.O.S. for Dogs.

The association also proposed a new bill that would make dogs the personal property of their owners (so they would have the same status and protection as horses and cattle), and that would hold dog owners responsible through civil court action for damage done by their animals (instead of killing the dog).

Despite everyone’s efforts, Governor Whitman signed the Wicks-Brown Dog License bill into law on June 30, 1917. The final law included a provision requiring that all law-breaking dogs be held 10 days before being killed; also, toy dogs under 10 pounds were excluded from the killing requirements.

Eighteen months later, the New York World reported that $279,000 in fees had been paid to farmers to cover losses or damages to not only sheep but to horses, cows, pigs, chickens, rabbits, and goats. Some small-town assessors and constables also made out well with their share of the fees.

The Waiting Years

Following the death of Grumpy in 1926, Emma and Henry Bizallion moved again, this time to a house on Brevort Farm Lane in Rye, New York. I’d like to think that they chose a home in Westchester County to be closer to the Hartsdale Pet Cemetery, the final resting place of their beloved Grumpy.

Grumpy did not have to wait long for Emma to join him in the afterlife. She passed away only nine years after his death on June 2, 1935, at the age of 64. She was buried in the Bizallion family plot at Pleasant View Cemetery in Middletown Springs, Vermont.

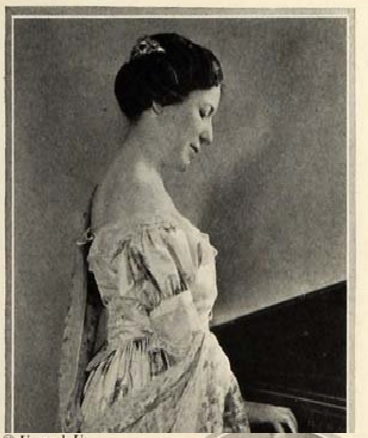

Henry, however, hung on much longer. Sometime around 1940, he married Lotta Van Buren, a renowned ancient instrument restorer, collector, and musician, and the grand-niece of President Martin Van Buren. She had taught piano in New York for many years — perhaps she taught Henry — before retiring in 1940. She moved to California and married her “old friend, himself a musician,” in Maricopa, Arizona, on April 6, 1940.

Lotta V. Bizallion died in May 1960. Henry joined his two wives and bulldog Grumpy on September 4, 1960, when he died in Santa Barbara, California, at the age of 90.