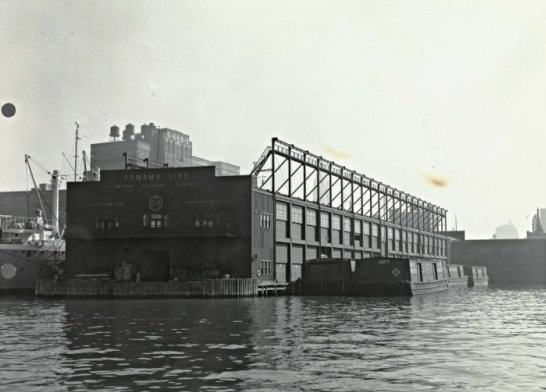

On August 18, 1912, the Anchor Line steamship Caledonia arrived from Glasgow at New York’s Pier 64 with numerous passengers – and 12,000 barrels of Scotch herring.

According to The New York Times, as the ship steamed up the Hudson River around noon, “all the cats along the waterfront left their respective piers and went running up West Street, meowing in chorus excitedly, with their tails in the air, to the Anchor Line dock.”

When Passenger Manager W.J. Reilly arrived on the scene, he asked the sailors what they were doing with all of the seafaring cats, as they were not allowed to have so many pets on the ship at the company’s expense. He knew that the ship already had one very popular ship’s cat , so he was quite confused about the clowder that had gathered along Pier 64.

It wasn’t until the ship pulled up to the pier and the barrels of herring were carried off that Mr. Reilly realized why so many felines were crying so lustily on the pier. (Duffy MacNab, on the other hand, probably thought all the cats — especially those of the female persuasion — were coming to welcome him.)

Duffy MacNab Joins the T.S.S. Caledonia

Launched in 1904, the twin screw steamship (T.S.S.) Caledonia registered at 500 feet and 9,223 gross tons out of the Glasgow Yard of D. & W. Henderson for the Anchor Fleet, the third vessel of five that would be so-named for the line. Powered by a massive steam engine, the British passenger liner could go up to 18 knots while comfortably accommodating 383 first-, 216 second-, and 869 third-class passengers.

From 1905 to 1914, the Caledonia was one of the premier passenger liners that steamed between Glasgow and New York City on a weekly basis. Her fastest passage (from Ireland) was 6 days and 20 hours. The rates for passage ranged from $67.50 to $125, depending on the accommodations.

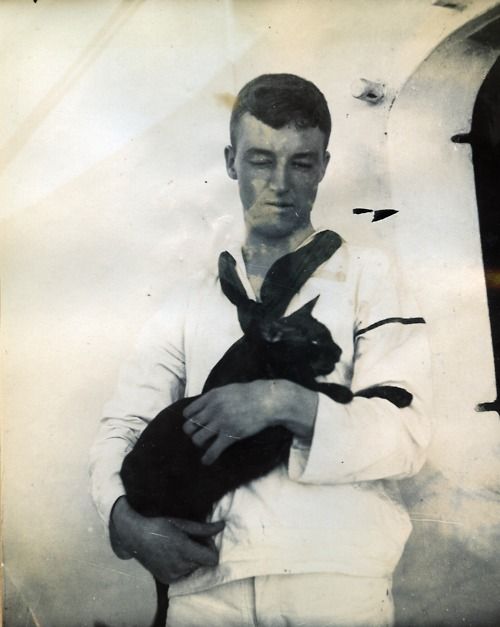

On March 25, 1905, Caledonia made her maiden voyage from Glasgow, Scotland, to New York and back. In addition to the passengers and crew, on board was a young black cat that the crew named Duffy MacNab — or The MacNab, for short. (The passengers called him Duffy MacNab, because that was the name engraved on his collar, but the men called him The MacNab.)

For the next eight years, Duffy MacNab sailed over 200,000 miles. He made 18 Atlantic crossings, and never once missed a trip either way. He was certainly on board on April 9 1912, when a sailor on the Caledonia, traveling eastbound from New York to Glasgow, transmitted a wireless message to the westbound Bulgaria warning of a large ice field that was likely the one subsequently encountered by the Titanic five days later.

Although he obviously loved sailing across the Atlantic, Duffy also enjoyed spending time ashore (he no doubt courted numerous lady cats of Glasgow and New York). He was always the first to land (by way of jumping from ship to pier) and the first to board (by way of the gangplank). As ship’s surgeon Dr. Jenkins told a reporter for The New York Times:

“When we quit the ship after our arrival in port The MacNab would always go, too, and would not, as a rule, be seen again until the day to sail rolled around, and then just before the gangplank was taken in he would come marching aboard with all the dignity and self-importance of the king of cats that he was.”

The MacNab’s Last Jump

When the Caledonia arrived at Pier 64 on August 3, 1913, it was Duffy MacNab’s 18th Atlantic crossing. As he had done numerous times before — albeit from a distance of only four feet — Duffy prepared to jump from the forecastle of the ship to the roof of the pier. But this time he tried to jump too far.

As The New York Times reported the next day:

“The mascot was looking at the roof of the pier and his attitude showed that he was figuring out whether or not he could make the jump from the liner to the pier roof, a distance of some ten feet… So he threw caution to the wind and jumped.

“His black body glistened in the sunlight, and then like a broken aeroplane it began to drop. Rocket fashion it fell through the air, and a moment later The MacNab struck the water. The sound of the splash was heard both on the pier and on the ship.”

Quartermaster Angus MacLean, aka, “The Kaid,” witnessed his beloved cat make his death leap. MacLean jumped overboard, dove under the pier, and tried to reach for MacNab. But by that time the cat had been carried away with the tide. After swimming for about 15 minutes, the grief-stricken sailor was hauled back on board.

As the other sailors gathered around MacLean, many of them had tears in their eyes. They had all loved their feline mascot, and his sudden death hit them all very hard. When Pursor Johnson and Dr. Jenkins went up to the forecastle to see what was wrong, they also joined in the mourning.

“We shall never see his like again, for he was indeed a rare cat. So loyal to the ship, and with it all so intelligent. It is hard to lose him,” said Pursor Johnson.

“Yes, indeed,” agreed Dr. Jenkins. “The MacNab was a most unusual animal. I have known cats in every port here and in Europe, but none of them could compare to poor old Duffy. He was an aristocrat through and through. He would only partake of the choicest food and was unusual in that he preferred tea to milk.”

The Caledonia Goes to War

One year after The MacNab’s death, the British government converted the luxury passenger liner into a troop ship capable of carrying 3,074 troops and 212 horses. For more than two years, the ship carried soldiers and their equipment to various locations around the Mediterranean.

On December 5, 1916, while carrying mail but no troops from Greece to France, Caledonia was torpedoed by the German submarine U-65. Although his ship was sinking, Caledonia‘s Captain James Blaikie steered the troop ship toward the U-boat and tried to ram her. Caledonia did hit the U-boat, but the U-boat stayed afloat as Caledonia sank about 125 miles east of Malta, with the loss of only one life.

Interesting post! It’s sad, though, that The MacNab met his end in such a way.