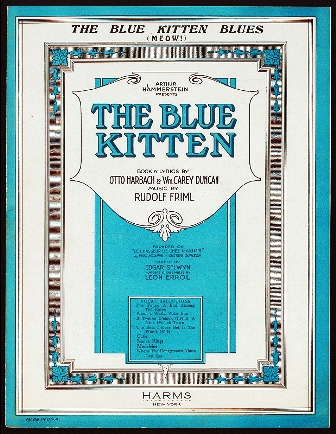

When we left Part I of this curious cat tale of Old New York, young Margaret Owen was just about to dunk Lilly and Otto, her two Angora cats, into a basin of blue dye. The blue cats, she thought, would match her blue suit and look great parading down the boardwalk at Atlantic City. They’d also make a great gift for Otto Harbach and Arthur Hammerstein, the writer and director of “The Blue Kitten.”

Margaret Owen was obsessed with the color blue. Everything in her apartment was blue, as were all her clothes and accessories. The petite singer had also recently auditioned for a chorus role in “The Blue Kitten,” which was appearing at the Selwyn Theatre (today, the American Airlines Theatre) on West 42nd Street.

So one day, while dying some old woolen stockings in a basin of blue dye, she got a wicked idea when her cat Lilly dipped her paw into the basin. She picked up the cat and dunked her right into the bowl of blue water. Then it was her cat Otto’s turn (I don’t know if this was his name, but several newspaper articles refer to him as Otto).

Despite the cats’ howls, Lilly held them down in the water for about five minutes until she was sure the dye had taken. (She took care not to immerse their heads – she used a piece of cotton dipped in the dye to swab their faces.) When she was all done, she wrapped the cats in an old blue towel and placed them on a blue cushion to dry.

Now, Margaret Owen was not the only person who rented an apartment from building owner Clarice Carleton Holland at 75 West 50th Street. Hearing the cats’ howls and thinking that Margaret was killing them, several neighbors called the Humane Society.

Over the next few days, things did not go well for poor Otto. Sensing something was wrong with the lackadaisical cat, Margaret took Otto to Dr. Harry K. Miller’s dog and cat hospital (aka, The New York Canine Infirmary), which was then located at 146 West 53rd Street. There, the blue Angora succumbed to an apparent poison in the dye.

Enter stage left, Harry Moran, Superintendent of New York’s Humane Society. Harry Moran told Margaret he was taking her and Lilly to the West Side Magistrates Court, where she would appear before Magistrate Peter A. Hatting on charges of animal cruelty.

Margaret put the blue cat in a blue silk bag and brought her to the court, where she was met by her attorney, Benedict A. Leerburger of the firm of House, Grossman & Vorhaus.

Magistrate Hatting ordered Margaret, Superintendent Moran, Mr. Leerburburger, and the cat to go to the Humane Society headquarters to have Lilly’s fur analysed by a chemist.

Pending the test results and Lilly’s status, the judge said, he would make his decision.

“If Miss Owens and Mr. Leerburger want any lunch, the Humane Society will supply them with it,” the judge reportedly said as he sent them on their way to have Lilly examined.

“What kind of lunch?” Mr. Leerburger asked the magistrate. “I can’t get along on a cat’s diet,” the attorney said. “I need more than milk for sustenance.”

Two veterinarians and a specialist on poison were called to assist with Lilly at the Humane Society. They washed the cat and had the water analyzed. It turned out that the blue dye contained 5% arsenic.

Because Lilly had licked a lot of the dye off and become very sick, the magistrate said it was almost a case of fatal poisoning. (Margaret denied knowing anything about Otto, claiming that he was a friend’s cat that she had taken to the animal hospital as a favor for her.)

Mrs. Anna Doyle, Margaret Owen’s probation officer, was convinced that Margaret had not intended to harm the cats. Lilly had survived the ordeal, so Mrs. Doyle asked the judge to go easy on Miss Owen.

“You’re a spoiled child,” the magistrate admonished Margaret during her sentencing. “What you need is a guardian. Are you married? No? Then I’ll send you back to your father until you get another guardian.”

In addition to remanding Margaret to her parents in Florida, Judge Hatting told her that the Humane Society would have custody of Lilly until her blue color had vanished.

Margaret’s Story Goes Viral

Within days after Margaret appeared in court with Lilly, the story of the blue-dyed cat that had died from dyeing (referring to Otto) made all the major newspapers across the United States. Her story was also cabled to the Paris newspapers, where the idea of dying your pets to match your wardrobe was much appreciated by the high-society Parisian women.

The Paris women were a little more intelligent, though. First, they thought it would be better to dye their dogs, since cats aren’t fond of parading about with their mistresses. They also found that coffee, caramel, or tea, mixed with cream (and a little bit of quinine to discourage licking), made a great safe dye.

Superintendent Moran was completely against this fad, and had a reputation for prosecuting those who tried it in New York City. Even if coffee, tea, and caramel was used, he said, these were poisonous for animals, and thus, punishable under the law as a misdemeanor crime against animals.

10 Years Later…

I do not know what happened to Margaret Owen and Lilly. Hopefully they lived happily ever after in Florida, but for some reason I don’t think Margaret kept herself out of trouble for the rest of her life.

What I do know is that in 1930, Clarice Carleton Holland, the widow of Dr. Bukk G. Carleton, sold the building at 75 West 50th Street to William F. Beach, who in turn sold it the Underel Holding Corporation on behalf of John D. Rockefeller. By 1931 the holding corporation had acquired all the lots on the street, giving them the entire 50th Street frontage on which to construct Radio City Music Hall.

Once upon a time, a young woman dyed her cats blue in an old brownstone and brick apartment on this very site at the northeast corner of W. 50th Street and Sixth Ave. Radio City Music Hall opened on December 27, 1932. Photo by P. Gavan

Incidentally, the animal hospital where Margaret Owen brought Otto and Lilly is still in operation as the Miller-Clark Animal Hospital in Mamaroneck, New York. Established in 1902 at 118 West 188th Street (according to old newspaper ads), it is one of the longest running veterinary practices in New York.