Part I of this Old New York cat tale begins in 1825 at the old John Leake Norton Hermitage Farm on the west side of Manhattan…

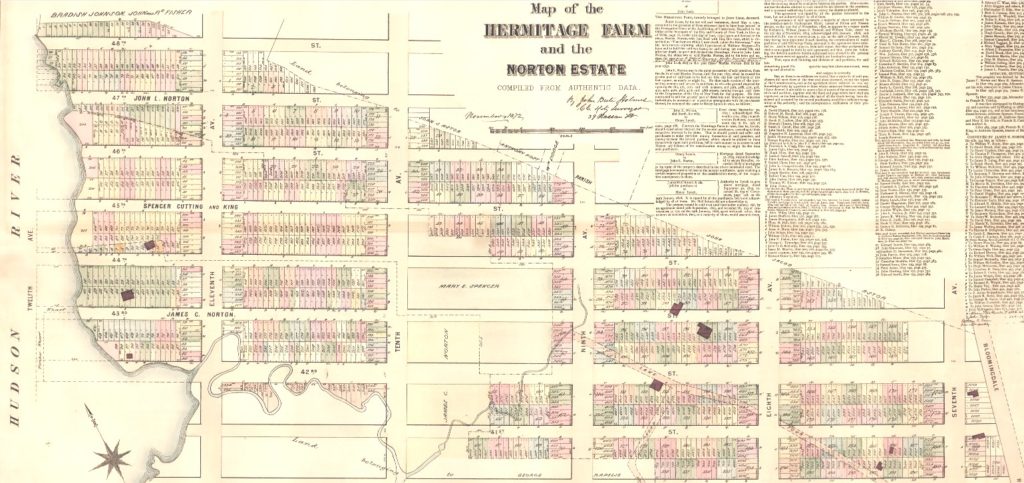

In 1825, John Leake Norton distributed some handbills advertising a raffle for his land on the west side of Manhattan. His plan was to divide his portion of the Norton Farm, aka The Hermitage Farm, into parcels of 4 to 16 lots, and sell them at a price beginning at $600 for the smaller parcels.

According to The New York Times, the drawing took place in the Shakespeare Tavern at Fulton and Nassau Street. “Over mugs of ale, between smoke rings drawn from long pipes, adventurous citizens bought the Norton farm.”

That same year, John Leake Norton ceded to the City of New York all that land which would be required to open 39th through 48th streets. The city paid him $10 for this land.

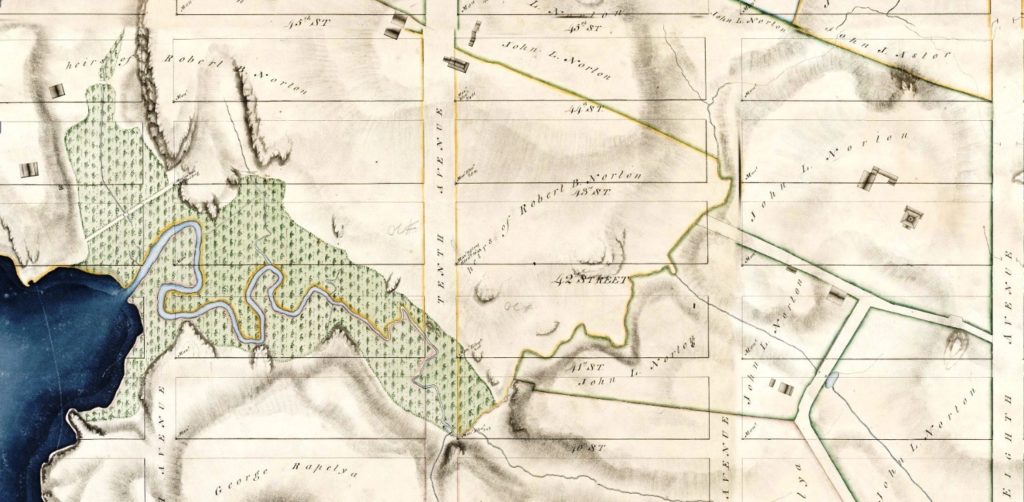

The Hermitage Farm had been in the family since about 1780, which is when John Leake purchased a tract of about 80 acres between present-day Broadway and the Hudson River from Matthew Hopper. Much of the property west of the Eleventh Avenue comprised “sunken lands” that were under the Hudson River and the Great Kill, a large stream that emptied into the Hudson at the foot of what is now 42nd Street.

When Leake died in 1792, he bequeathed the land and the home he called The Hermitage to his niece, Martha, the wife of Samuel Norton. Upon her death in 1797, the property passed on to her sons John Leake Norton, Samuel John Leake Norton, and Robert Burridge Norton.

In the years following the sale of the Norton Farm, residential development was brisk, particularly after the city’s first street railway — the New York and Harlem — began running from Prince Street to the Harlem Bridge in 1832. Commercial development also picked up along the Hudson River after the sunken lands of the old Hermitage Farm between Eleventh Avenue and the Hudson River were filled in to create Twelfth Avenue in 1862-63.

The Green Line Car Stables

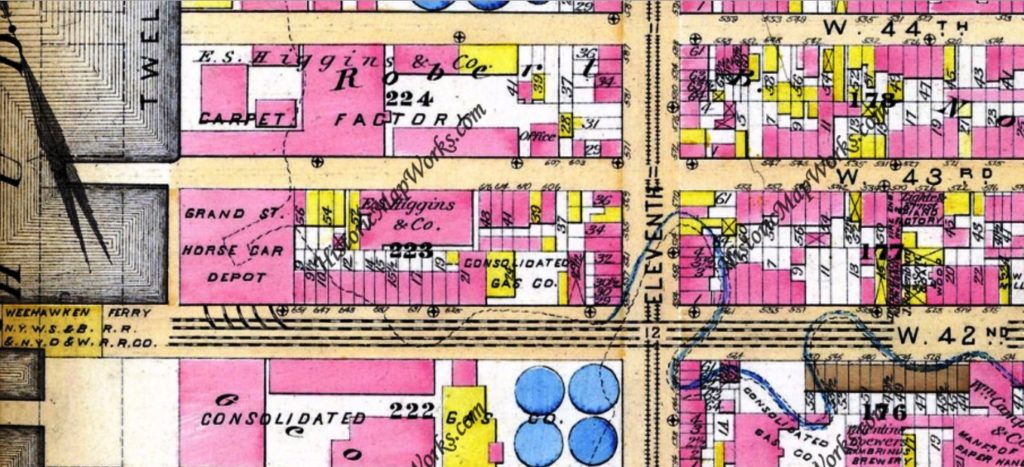

In 1864, the car stables of the Forty-second-Street and Grand Street Ferry Railroad were constructed on land that had once been under water, on the east side of Twelfth Avenue at the foot of 42nd and 43rd streets. Immediately to the south of the three-story brick car stables was the large Consolidated Gas Company, and just to the north was the E.S. Higgins & Co. Carpet Factory.

The Forty-second-Street and Grand Street Ferry Railroad, also known as the Green Line because of the green lights on the cars, was a horse-drawn streetcar line that ran a zigzag path from the Weehawken Ferry (the West Shore ferry terminal) at the foot of 42nd Street to the Grand Street Ferry on the East River.

Approximately 570 horses were stabled in the Green Line car stables, along with about 50 trolley cars plus all the harnesses, bales of hay, and other equipment required to care for the horses.

The Great Car Stables Fire

At about 10:30 p.m. on June 12, 1886, night watchman John Horner noticed smoke coming from the third-floor paint shop at the northeast corner of the car stables. He ran out and sounded the alarm, but by the time the fire engines arrived a few minutes later, the entire stable, covering 8 lots on 42nd Street, 8 lots on 43rd Street, and the entire river front, was on fire.

At the time of the fire, about 565 horses were in the building, including five that were upstairs in a special hospital for the horses. One sick horse was in slings awaiting treatment.

Under the direction of Superintendent John M. Calhoun, all of the employees on site were able to lead the horses safely outside (quite an amazing feat, considering that most car stable fires of this period resulted in the deaths of hundreds of horses). Only one horse — the one in slings — perished in the flames. The other horses were taken to Justice Murray’s coach lot on 42nd Street between 10th and 11th Avenue.

After all the horses were out, the men focused on saving the cars by pushing them out on the tracks along 42nd Street. All but 4 cars were saved, and almost all but 40 harnesses were also saved.

While all this was going on, about a dozen or more cats that lived in the stables, including one especially brave tabby, were fighting for their lives as the building continued to burn all around them…

In Part II, I’ll tell you what happened to the cats, and how one very brave cat found a new home at a firehouse in Chelsea following this event.

[…] 1886: The 10 Lives of Hero, the New York City Fire Cat of Chelsea, Part I […]