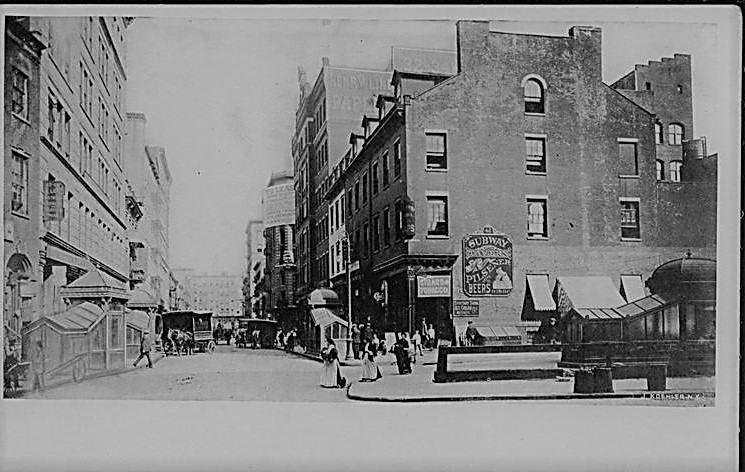

For 40 years, Fred Sauter stuffed every kind of animal imaginable in his workshop at 42 Bleecker Street, pictured here on the right sometime around 1905. Note the entrance to the brand-new subway in the foreground, at the intersection of Mulberry Street and Elm Street (today’s Lafayette Street).

In the first part of this Old New York menagerie tale, we met taxidermist Fred Sauter Jr., a well-known New York City taxidermist who did a thriving business stuffing deer, bears, lions, birds, monkeys, and even pet dogs and cats in his large warehouse at 42 Bleecker Street. In Part 2, we’ll explore the history of the building on Bleecker Street where Fred Sauter Jr. and his son turned the skins of dead animals into fascinating if not grotesque displays for hunters, department stores, theater sets, movies, and distraught pet owners.

The Old Bayard and Bleecker Farms

The recorded history of the area where this story takes place begins in 1644 when William Kieft, the Director General of the New Netherlands, transferred property to freed African slaves. This was no act of kindness: In fact, the Dutch wanted their former slaves to live in this uncharted territory in order to protect the settlement of New Amsterdam by serving as buffers against invading Native Americans.

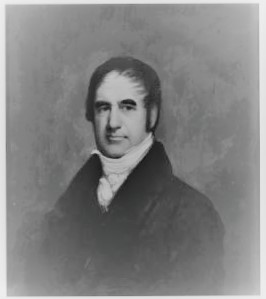

Anthony Bleecker (1770-1827) deeded a major portion of the family farm to New York City in 1808.

By the late 17th century, what was called the “negroes land” had been sold to large landowners, including Nicholas Bayard, whose Bayard farm was split in 1775 when Great George Street (Broadway) was cut through the property. The Bayard farm was conveyed to trustees in 1789, who in turn sold individual lots and acreage to Aaron Burr and Anthony Lispenard Bleecker,

Anthony Lispenard Bleecker was prominent banker, merchant, and auctioneer, and a vestryman and warden for Trinity Church. Born in the town of New Rochelle (Westchester County, New York) in 1741, Anthony was the son of Jacobus Bleecker and Abigail Lispenard. The Bleecker family lived in a residence at 74 Broadway, across from Rector Street near the church.

When Anthony purchased 160 acres “out in the country” in 1790, his friends reportedly laughed at him for wasting his money. His son, also Anthony, inherited the farm, and in 1808 deeded a major portion of this land to the city. The city divided and sold off the lots to people looking to escape the squalid and crowded conditions of lower Manhattan.

42 Bleecker Street: 1854-1892

Fast-forward about 50 years to 1854, when a new four-story brick building at 42 Bleecker Street caught the eye of Thomas Nelson & Sons. Nelson, the largest printing and publishing house in Scotland, was looking to expand overseas, and Bleecker Street was the perfect location for their new offices. Here, for about 20 years, they printed the Oxford edition of the New Testament and Old Testament of the Bible.

On August 30, 1892, about 30 years after Thomas Nelson & Sons moved into the building, the steamship Moravia arrived from Europe. Reportedly, 22 people had died on route from cholera. Ten days later, another ship arrived, which reported 32 cholera deaths at sea. New York City was not about to take any chances.

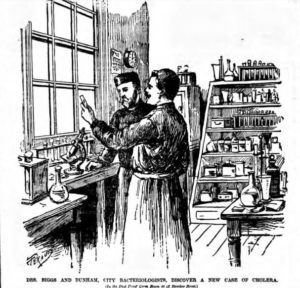

Dr. Herman M. Briggs in his laboratory on the third floor of 42 Bleecker Street in 1892.

One month later, in September 1892, the city’s Board of Health created a laboratory consisting of a few rooms on the third floor of 42 Bleecker Street as part of the agency’s new division of pathology, bacteriology, and disinfection.

There, Dr. Herman M. Briggs, a prominent figure in the history of public health who had studied in Germany and trained at Bellevue Hospital Medical College, went to work waging a war against cholera, diphtheria, and tuberculosis.

Today, the tiny laboratory at 42 Bleecker Street founded by Dr. Briggs in 1892 is located in a 14-story building on First Avenue and 21st Street. Called the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, it employs hundreds of scientists who track diseases like AIDS, Ebola, and the West Nile virus.

Following the Lord and Chasing the Devil

On August 3, 1904, Joe Johnson opened the Subway Tavern in the basement and ground floor of 42 Bleecker Street. The “tavern” was consecrated by Bishop Henry Codman Potter, the Bishop of New York, former rector of New York City’s Grace Church, and the brainchild behind the Subway Tavern.

Although other saloons were under attack at this time by Church Temperance Society prohibitionists, the Subway Tavern promised to offer an alternative option for those who wanted their liquor and a touch of religion, too. The family-friendly tavern featured a soda water store in the front (called the Water Wagon), where women, men, and children could buy soda (wink wink). Behind this room was a smaller room intended as a reading room, and behind that, a bar and cigar room where liquor was served and women were prohibited.

In the basement was a rathskeller where free lunches were served at noon. The outer walls of the building were reportedly painted with spiritual texts.

From August 1904 to August 1905, Joe Johnson operated the Subway Tavern at 42 Bleecker Street. To the right on Mulberry Street was the St. Barnabas Home for women and children (opened 1863) and the headquarters of the New York City Police Department. To the left, in the white building at 38 Bleecker Street, was the St. Barnabas’ Free Reading Room for “well-behaved men,” which opened in 1867.

Members of the Church Temperance Society were totally outraged by the saloon and the fact that women could drink beer in the soda water store. They were not too pleased with Bishop Potter, to say the least.

The tavern never managed to make a profit, and one year later it was purchased by William G. Skidmore, the manager of the rathskeller restaurant, who planned on running the place as a straight saloon and restaurant without the soda section. As the “red faced and rotund” Skidmore of Brooklyn told the press, “You can’t follow the Lord and chase the devil at the same time. Rum and religion won’t mix any more than oil and water.”

The End of an Era

In 1947, the year Fred Sauter retired, 42 Bleecker Street was replaced by the new St. Barnabas Home (completed in 1949).

Apparently Mr. Skidmore’s venture was no more successful than the Subway Tavern, because by 1906 Fred Sauter had moved into the ground floor of the building with his taxidermy workshop.

He continued stuffing lions and tigers and cats and dogs and sharks and elephants at this location until retiring in 1947 at the age of 74.

That year, the old building at 42 Bleecker Street was torn down to make room for a new St. Barnabas House at 38-42 Bleecker (alt: 304-308 Mulberry Street), headquarters for the New York Protestant Episcopal Mission Society.

The T-shaped, four-story building featured two landscaped courts; a laundry and kitchen in the basement; lounge, interviewing room, chaplain’s office and chapel on the ground floor; bedrooms for women and children on the second and third floors; nursery on the fourth floor; and a play porch and roof deck on the roof.

Fred Sauter III, in front of his and Elmer Rowland’s shop at 501 Avenue of the Americas in 1959.

Fred Sauter’s son, Fred Sauter III, continued in the business with partner Elmer E. Rowland in Rowland’s shop at 501 Avenue of the Americas until 1959, the year Fred’s father died.

As the 69-year-old Fred told the press, with all the old estates of the Vanderbilts, Goulds, Astors, and Belmonts gone, no one had the wall space to hang their stuffed hunting trophies and there was simply no longer a high demand for other stuffed animals.

“Some of the specimens in the old days would take up a whole wall in somebody’s mansion,” he told The New York Times. “Now who has a wall that big?”

A new building was constructed at 38-42 Bleecker Street in 1974. Called Mulberry North, it features 92 residential units that are reportedly converting to condos in the near future.