In 1915, the Bowling Green Neighborhood Association established a community center at 45 West Street. The four-story building housed a day nursery, library, and rooms for English instruction, household arts, citizenship classes, and various clubs. The community playground was behind the wall to the right in this photo.

In 1917, the president of the Bowling Green Neighborhood Association (BGNA) came up with a plan to help control the feral cat population in Manhattan’s Lower West Side. Dr. Miner C. Hill, a pediatrician in charge of the nonprofit association’s baby clinic, believed that the stray cats were responsible for spreading diseases to the poor immigrant babies and children under his care.

Dr. Hill’s idea was to offer a nickel to every neighborhood child who captured and delivered a stray cat to the Bowling Green Community Playground on West and Washington streets. There, the cats would be placed in boxes and carted off to the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals “to finish the job.”

For the next 10 years, the annual cat roundup — or annual Bowling Green cat massacre as I prefer to call it — resulted in the murder of thousands of cats and kittens at the hands of little children and the SPCA. (The association claimed that the roundup of stray cats was done “for humanitarian purposes” because the cats were sick and starving; unfortunately many healthy cats were also captured during this annual open season on felines.)

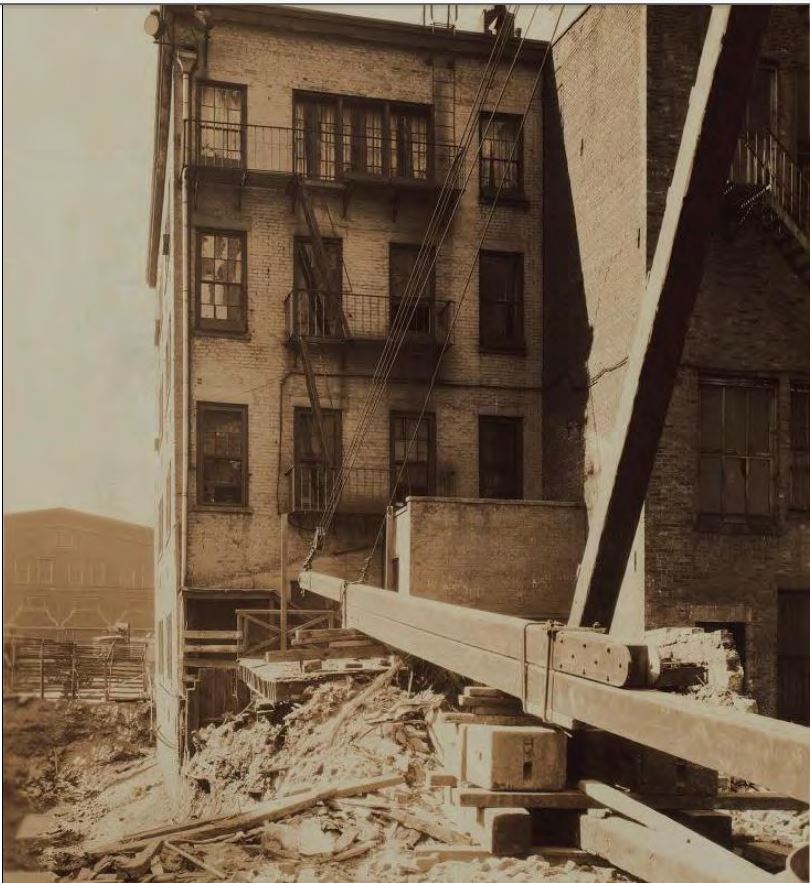

The New BGNA Headquarters at 105-107 Washington Street

In Part I of the Bowling Green Cat Massacre, we left off in 1925, which is the year the Bowling Green Community Playground was dismantled to make way for development. That year, the BGNA moved out of the circa 1845 tenement building at 45 West Street and laid the cornerstone for its new headquarters just up the road at 105-107 Washington Street.

In 1925, the Bowling Green Community Playground adjacent to 45 West Street was demolished to make way for new apartment buildings. This photo from 1925 shows the rear of 45 West Street with new construction in progress.

Here’s 45 West Street in 1927 (right side), two years after the BGNA moved out. The building was demolished in the 1940s when the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel was constructed; in 1950, the year the tunnel opened, Crystal Street–later renamed Joseph P. Ward Street–was opened in the block between Washington and West streets where #45 had once stood. The stairway for the West Thames Street Pedestrian Bridge, scheduled to be completed in 2018, will be on this very site.

In 1925, a small group of businessmen headed by William H. Childs, the founder of the Bon Ami household cleaner company, donated $300,000 for the construction of a new six-story, five-bay red brick building at 105-107 Washington Street.

The new BGNA headquarters–called the Downtown Community House–featured a roof playground, gymnasium, day nursery, library, cooking school, dress-making school, and auditorium. The first floor was devoted to public health activities. The upper floors were tenements featuring cement floors, shower baths, and toilets, which were rented to local immigrants for $5 a month.

The building served as the BGNA headquarters until 1940, which is when the BGNA, Beekman Street Hospital, and the Downtown Community House were consolidated as Beekman Hospital.

The new Bowling Green Neighborhood Association headquarters at 105-107 Washington Street was constructed on land that was originally part of a larger tract purchased in 1799 by George Pollack, an Irish-born importer of Irish linens. The new headquarters replaced the two white-brick tenements pictured here in 1911. These circa 1820s buildings were boarding houses for Irish immigrants and sailors in the 1860s and later housed Syrian immigrants until the buildings were demolished in 1925. The taller apartment building to the left is still standing.

The building at 105-107 Washington Street is one of only three structures from the “Little Syria” neighborhood still standing. At right, #103 is circa 1812 structure that was converted in 1925 for use as the St. George’s Syrian Catholic Church. On the left, #109 is a 19th-century tenement building that is still a residential building today. The building at 105-107 is currently vacant, and a recent sign says the entire building is for lease.

The Last of the Bowling Green Cat Massacres

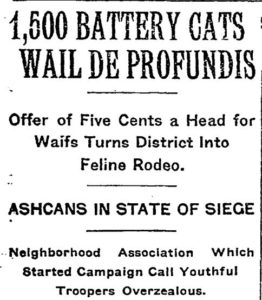

In 1923, about 1,500 cats were rounded up at the Bowling Green Community Playground. But things got out of hand when the “humanitarian” event turned into a commercial venture. Reportedly, the little urchins tried to boost their nickel profits by rounding up pet cats as well as strays.

The New York Times, October 27, 1923

The New York Times reported that one child tried to get 15 cats living with a woman in the tenements above the community center at 107 Washington Street. When the woman saw the boy and his friends approach, she opened up her kitchen window and let all her cats escape.

Another little boy tried to catch a house cat that also got away — but not until its rightful owner discovered the thief and chased after the child.

As playground director John Hennessey told the reporter, “If a cat so much as sticks his head around an ashcan, he’s a goner. His life isn’t worth a thing.”

The association released a statement that year admitting the children were a bit “overzealous”:

“We are afraid that some of the youngsters were overzealous in their round-up and many a dearly beloved house pet or visiting aristocrat was involuntarily dragged along to join the crusade. However, the edict included all unchaperoned members of the feline family, and any valued and pedigreed pet that was left unguarded on that appointed day of wrath we fear has uttered its last ‘meouw.'”

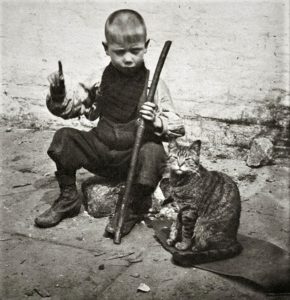

Spurred on by nickels and show tickets, young children became more than eager cat hunters during the annual Bowling Green cat roundup.

In March 1925, one month before the Bowling Green Community Playground closed, the BGNA held its last annual cat roundup at the playground.

That year, the association collected 75 boxes of cats. Each child was awarded with a prize of two tickets to a “cat party” at the Downtown Community House for every cat captured.

One elderly woman who said she had no interest in children and claimed to belong to every humane society in the city tried to stop the event by chasing the children away. Unfortunately, her efforts were all in vain. (Her letter to the editor of The New York Times condemning what she called the “cat crusade” appeared on April 9, 1925.)

The New York Times, March 29, 1925

In 1926, the year its community playground closed down, the Bowling Green Neighborhood Association hosted the very last cat roundup at Bowling Green, New York City’s first public park.

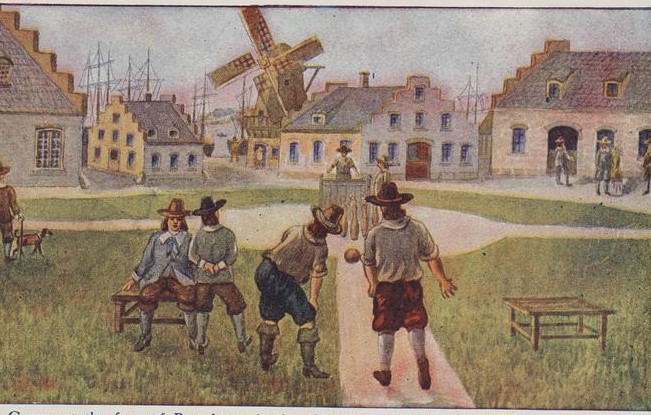

According to legend, Native American tribal leaders once used the land around Bowling Green for meetings and to negotiate the sale of Manhattan to Peter Minuit in 1626. The site was used as a parade ground and cattle market during the Dutch era through 1664, and declared public property by the British in 1686.

On March 12, 1733, the land was leased for one peppercorn a year to John Chambers, Peter Bayard and Peter Jay, who improved the site with a bowling green, trees, and a wood fence (the iron fence still standing was installed in 1771). The public gained full access to the park in about 1850.

Bowling Green was laid out in 1733 as an actual bowling green, depicted here in this 1914 illustration. Museum of the City of New York collections.

Bowling Green as it appeared around 1826. MCNY collections

Bowling Green around 1860, 10 years after the public was granted full access. MCNY collections

In July 1926, newspapers across the United States reported on the Bowling Green cat hunt, noting that most of the victims were house cats who were captured and returned to their owners up to three and four times during the day (Tom, a school janitor’s maltese with only one eye, was caught three times). The public cried cruelty again, and this time the BGNA decided enough was enough.

At last, the annual Bowling Green Cat Massacre came to an end.

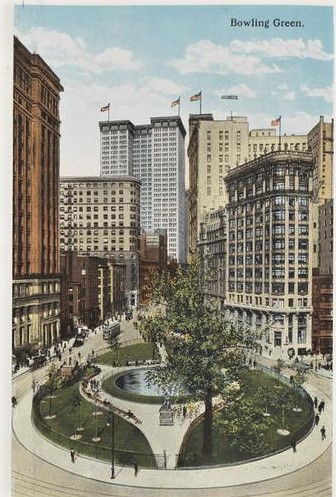

Bowling Green in 1917. MCNY collections