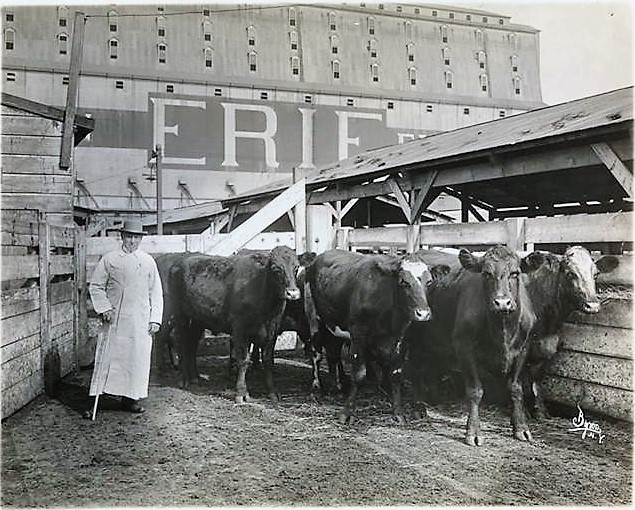

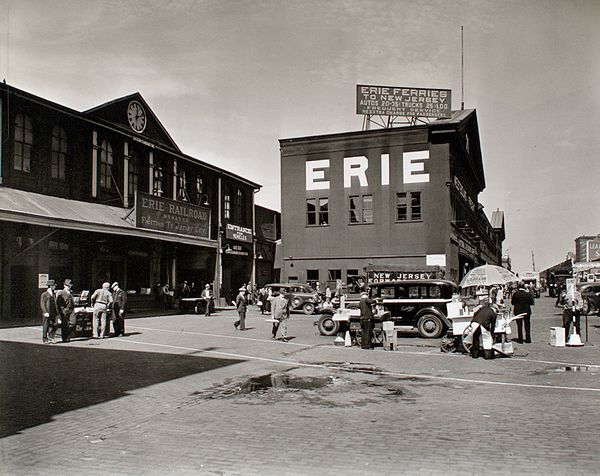

The cows that went wild on West Street in 1896 were being transported from Staten Island to the stock yards in Jersey City via the Erie Railroad Pavonia Ferry. Here are the stock yards pictured in 1913. Museum of the City of New York Collections

When New York City Policeman James Breen joined the Leonard Street Station in the late 19th century, he probably never dreamed that one day he’d have to play the role of a Wild West cowboy in Manhattan on West Street, at the Chambers Street Ferry Terminal.

In the late 19th century, West Street was always crowded in the afternoons during rush hour, even on Saturdays. The main thoroughfare was especially busy near the Chambers Street Ferry Terminal, where thousands of men, women, and children boarded the Erie Railroad Pavonia Ferry to Harsimus Cove in Jersey City, New Jersey.

On Saturday, January 23, 1896, Policeman Breen was on crossing duty at the ferry terminal when he saw about 20 women and children who were just about to cross West Street scatter in every direction. Turning around to see what had caused the commotion, he saw a herd of cows charging toward him. Within seconds, he was knocked to the ground.

Not about to let a herd of 16 cows ruin his day, Breen stood up, dusted himself off, and arrested the drover, 25-year-old blacksmith William Kane of 853 Pacific Street in Brooklyn. Breen charged the young man with violating a city ordinance that prohibited anyone from driving cattle through the streets of the city without a permit between 8 a.m. and 10 p.m. (Laws of 1872, chapter 776.)

The Pavonia Ferry house at the Chambers Street Ferry Terminal was constructed in 1872, the same year the city passed a law forbidding cattle driving on city streets during daytime hours. This picture was taken in 1896, the same year that our story of cows gone wild takes place. Museum of the City of New York Collections

William Kane told the officer that he had been hired by Thomas E. Wheeler, a prominent cattle dealer in Brooklyn, to take the cows from Staten Island to the stock yards adjacent to the Pavonia Ferry Terminal in Harsimus Cove. Kane did have a permit, but it had been issued in Brooklyn in 1894 and was thus no longer valid.

Policeman Breen left two other policemen and a few young boys at the scene to drive the cattle into a temporary corral while he took Kane to the Leonard Street station. There, an inquiry at the Board of Health office showed that Wheeler had no permit for Manhattan, so the arrest was justified.

Policeman Breen was attached to the 8th Precinct station house at 19-21 Leonard Street. Built in 1868 as a dwelling, it was remodeled in 1869 for the 5th Precinct (the 5th became the 8th Precinct on May 1, 1898). This precinct was abolished and the building was closed on December 1, 1913. The building was converted into condo lofts in the mid-1990s.

Following the arrest, Captain Cross gave Breen some money and told him to buy 50 yards of stout rope for capturing the cattle. Sixteen patrolmen were sent to assist Breen, including Roundsman Leonard, who had some experience as a cowboy a few years prior in New Mexico. The rope was cut into 16 pieces, one for each officer and their respective cow.

By this time, the cattle had become restless, and some had escaped from their temporary corral. It was quite the scene as hundreds of commuters gathered to watch the city cops lasso the cows and attach their ropes to the cows’ horns. When every cow was captured, the policemen walked them to Clark’s stable at 31 North Moore Street, where each cow had a stall to herself. The plan was to feed and milk them at Thomas Wheeler’s expense at the rate of $2 a day each until, if necessary, they could be “impounded” at the city pound at 183rd Street.

Nine months after the cow incident, the Pavonia Ferry house was partially destroyed by fire. Policeman Mackay of the Leonard Street station discovered the blaze in the telegraph room about 8:30 p.m. on October 6, 1896. By the time the first engines arrived, the fire had spread and smoke was pouring from the cupola, where 200 pigeons had made their home (the birds reportedly hindered the firemen’s efforts). The flames were confined to the attic, where the ferry records were kept, and no one was injured.

Seven years later, the Erie Railroad announced plans to construct a wide pedestrian bridge connecting its new 16-story office building on West Street to the ferry house. The new bridge allowed passengers to safely cross the busy street and easily board the new double-decker ferry boats without having to worry about cars, cows, or otherwise.

Passengers on a crowded Erie Railroad Pavonia Ferry boat (the J.G. McCullough, built in 1891) in 1896. Museum of the City of New York Collections

Thomas E. Wheeler and Brothers

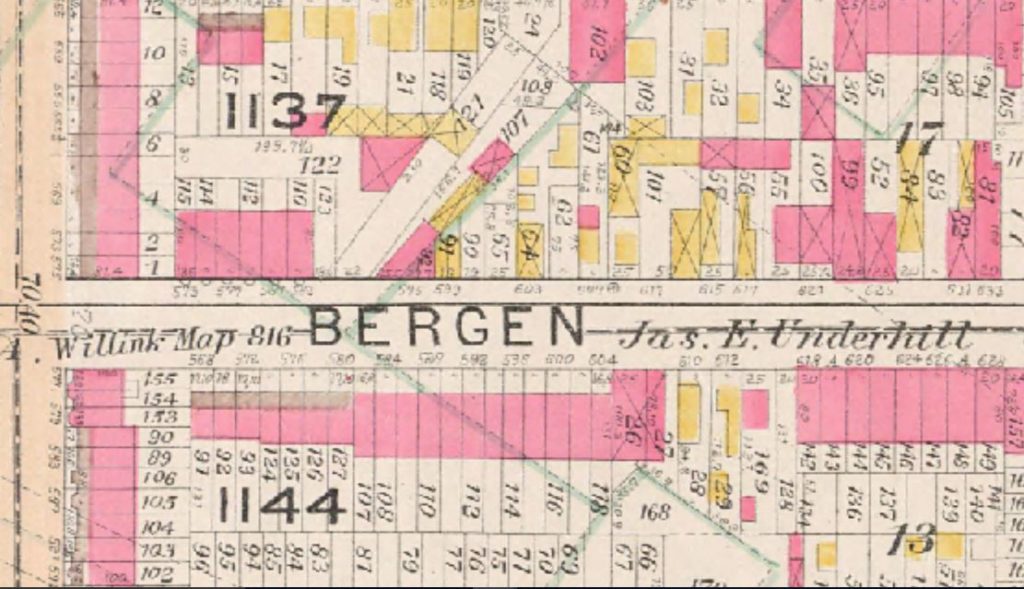

The incident on West Street in 1896 was not the first time cattle dealer Thomas Wheeler and his brothers, John and James, had been in trouble with the law, nor was it the last time. The brothers, who operated a large stable at 603 Bergen Street in the Prospect Heights section of Brooklyn, were often in the news whenever their cows escaped.

The Wheelers had a large, two-story stable with open-lot pastures at 603 Bergen Street (above the “E’ in BERGEN on this 1898 map), and later, at 617 Bergen Street. The original stable caught fire in 1906, killing 35 horses and threatening the lives of the residents of the surrounding two-story frame houses at #601 (occupied by John Shea, a milkman) and #605 Bergen Street (occupied by John Smith, Henry King, and Philip and Marie Bradley).

In April 1885, one of the Wheelers’ cows being driven from their establishment on Bergen Street to the farm of Mrs. Farrell on Fourth Street (between Bond and Hoyt) escaped and charged after a group of children on Third Street. Three-year-old Janet Moynahan was severely injured—several broken bones—which resulted in a case law titled Moynahan vs Wheeler et al. Although the Wheelers were originally charged and fined, the decision was reversed on appeal because it could not be proven that the Wheelers knew that the cow was vicious before it charged the girl.

Donovan Wheeler, a seminarian of the North American College in Rome, was the only son of Thomas and Mary Wheeler. He died in 1903 at the age of 22 at the family’s home at 138 St. Marks Avenue. Donovan had been fluent in Spanish, which came in handy during the Spanish-American War, when his father’s business conducted large cattle transactions with Cuba.

In 1907, one of their Holstein cows and her calf were being driven past the Board of Health offices at Sixth Avenue and 55th Street during broad daylight when the driver was arrested for violating the city ordinance.

In this incident, Probationary Health Officer Robert Dawson took charge of the cow and used his derby hat as a milk pail as he milked her right on the sidewalk.

“I thought she needed milking,” Dawson told the press. According to news reports, a young boy who witnessed the event said, “Gee, I always thought it came from bottles.”

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, members of the Wheeler family lived in several new brownstone townhouses on St. Marks Avenue between Carlton Avenue and Vanderbilt Avenue (sometime around 1860, this land had been occupied by the Wheeler family farm).

Thomas E. Wheeler and his wife Mary Donovan Wheeler lived at #138, James B. Wheeler and his wife Louise F. Hartigan Wheeler lived at #201 with their seven children, and John Donovan (Mary’s father), a prominent builder who developed all the lots from about #122 to #144, lived at #144 St. Marks Avenue, constructed in 1885.

In the late 1800s, John Donovan lived at 144 St. Marks Avenue (left) and Thomas E. Wheeler lived at #138 (far right). All of the Neo-Grec style brownstones were designed by architect Marshall J. Morrill and constructed on the former Wheeler farm in the 1880s, at a time when speculative residential development in Prospect Heights increased in response to the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883.

A Brief History of the Pavonia Ferry

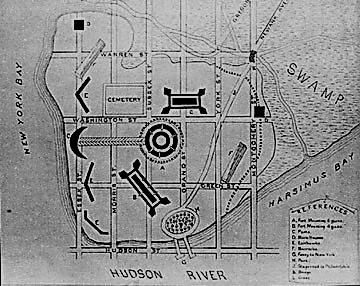

The Pavonia Ferry began running in 1851, along a route from Powles Hook (Paulus Hook) in the Harsimus Bay to Cortlandt Street in Manhattan. This route had been established around 1764 by Cornelius Van Vorst, then one of the richest men in Bergen County, New Jersey.

Cornelius reportedly had several flat boats for ferrying wagons and coaches and some smaller boats for passengers. He also owned a mile-long circular racetrack that went around Paulus Hook as well as a one-story tavern called Ellsworth Tavern, which was near the ferry docks by present-day Grand Street and Hudson Street.

Cornelius Van Vorst’s ferry dock is noted in this 1779 illustration by the letter “G” under the piers on Hudson Street at the foot of Grand Street. Today, this is the exact location of the Jersey City 911 memorial. Paulus Hook is still a very active stop for numerous ferries.

The Paulus Hook to Cortlandt Street route was picked up by Nathanial Budd sometime before 1802, which is the year he got permission to expand his “Budd’s Dock” at Paulus Hook. In 1803, Budd advertised that he had “good boats and careful ferrymen for carrying passengers, horses, cattle, carriages, goods, wares, and merchandise” to and from New York City.

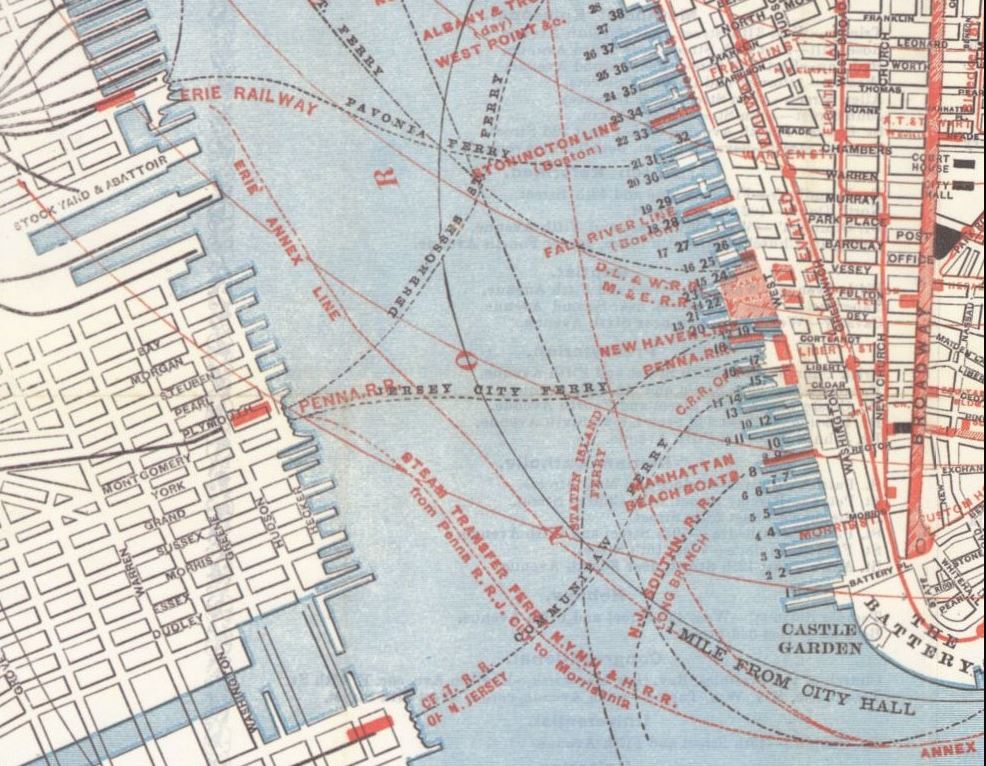

By the late 18th century, there were numerous ferry routes on the Hudson River. Note the Pavonia line and the Erie Railway stock yards at the top of this 1878 ferry route map; at the bottom is the Communipaw Ferry, which was started by William Jansen in 1661 and was the first legally established ferry connection between the two states. This ferry ran from the Central Railroad depot in Jersey City to the foot of Liberty Street; during the 17th century, it only operated on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, and the fare was paid by guilders in wampum (it cost 4 guilders in wampum for each cow).

Here’s another view of the Chambers Street Ferry Terminal in the late 19th century. In this photo, the Pavonia Ferry and Erie Railroad Company signs are missing, which indicates this photo was taken during a different time period than the photo above from 1896.

Additional daily service from Pavonia to a new terminal at 23rd Street in Manhattan, pictured here, began in 1869.

A new Erie Railroad terminal for its Pavonia Ferry opened in 1887. Besides the railroad and ferries, the complex was served by streetcars and the rapid transit Hudson and Manhattan Railroad (now PATH).

The Pavonia Ferry was taken over by the Erie Railroad Company in 1854 and sold to the Pavonia Ferry Company of Jersey City for $9,050.

Although a number of people had petitioned for ferry service from Harsimus Cove to Chambers Street in 1818, it wasn’t until February 1859, when Nathaniel Marsh of the Erie Railroad Company purchased the lease on behalf of the Pavonia Ferry Company, that service from Chambers Street to Jersey City commenced.

Ferry service between Chambers Street and Harsimus Cove in Jersey City ended in 1958 when the Erie Railroad moved its passenger services to the Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad’s Hoboken Terminal at 1 Hudson Place.

The Hoboken Terminal (aka Lackawanna Terminal) was constructed in 1907, when this photo was taken. Today this terminal serves several NJ Transit commuter trains, the Hudson-Bergen Light Rail, the PATH trains, and the NY Waterway ferry.

The Erie Railroad Pavonia Ferry at the Chambers Street Terminal in 1938.

The Demise of the Chambers Street Terminal

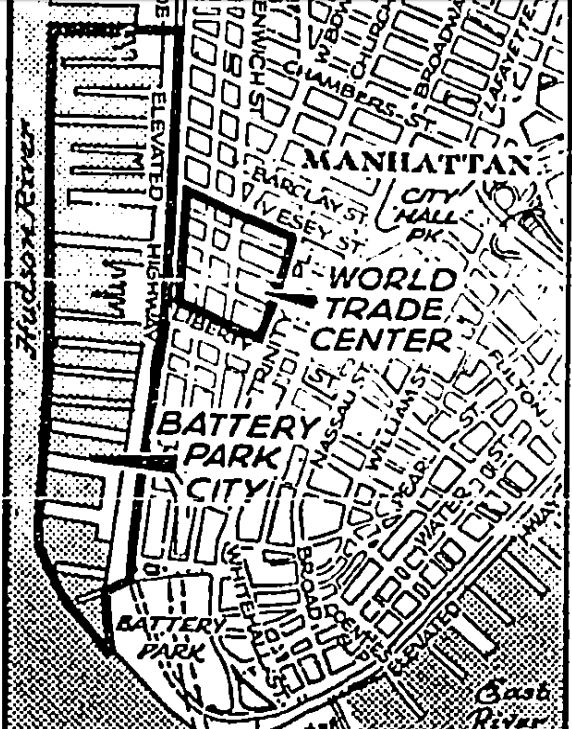

In May 1966, New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller and New York City Mayor John Lindsay proposed the construction of a “coordinated community” of offices, light industry, and housing on 98 acres of landfill extending from the Battery at Manhattan’s southern point to Chambers Street. Called Battery Park City, the project was expected to cost $1 billion.

The plan was to construct a bulkhead and dump rocks, dredged-up sand, and other materials excavated from the site of the World Trade Center and a water tunnel into the river (45 feet deep) to create a base level with the ground. In order to make room for this new landfill city, 17 dilapidated piers on the Hudson River along West Street–including the old Chamber Street Terminal and Liberty Street Terminal piers–were demolished.

The plans for Battery Park City and the World Trade Center in 1969.

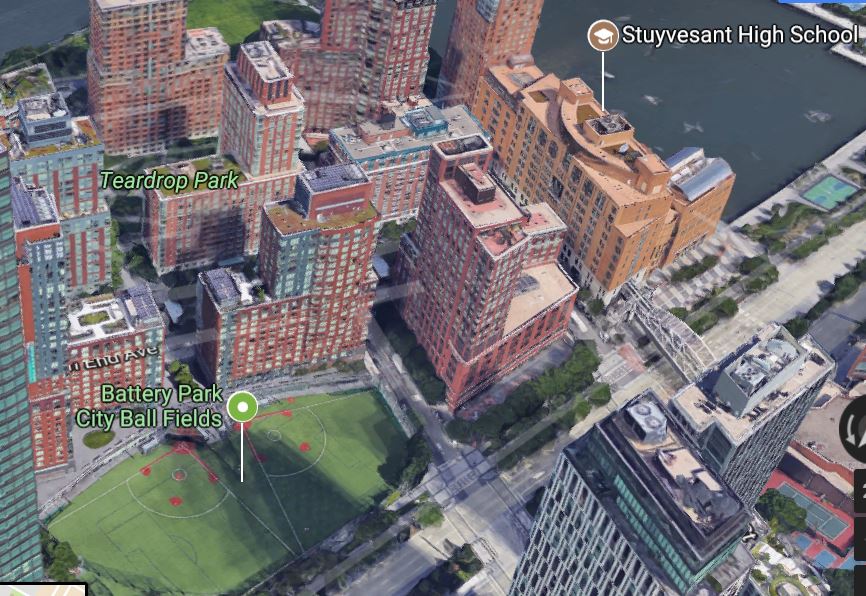

Today, the site where cows once trampled Policeman James Breen is occupied by apartments, Stuyvesant High School, and the Battery Park City ball fields.

Marvelous post! Fascinating. I so enjoy your blog.

I’m so glad you enjoy it! I’m working on a book right now, so I won’t be posting too often during the next few months, but I’ll try to write a new story every month until my book comes out.