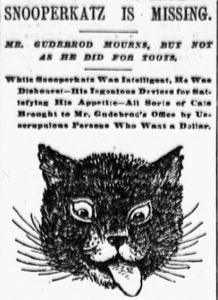

Snooperkatz got a lot of press when he went missing from The Gudebrod Brothers Silk Company at 644 Broadway in Greenwich Village.

Christian Gudebrod, a man described as “handsome with a clear, pink complexion and a long, straight blond mustache,” was a prominent manufacturer of silk sewing threads in New York City and Pennsylvania. One of seven brothers whose family had emigrated from Germany to Connecticut in the mid-1800s, Christian was instrumental in founding The Gudebrod Brothers Silk Company, Inc, a family-run business that went on to make medical cords, fly-fishing thread, and braided lacing tape for the aerospace industry until it went out of business in 2010.

Christian Gudebrod was also a cat man. Not quite a crazy cat man, but definitely a cat lover. To be specific, a cat man who loved one cat in particular–a smart and mischievous feline named Snooperkatz.

In the second week of May 1894, Christian Gudebrod distributed a flyer for his beloved shop cat Snooperkatz, who had gone missing from his office at 644 Broadway. The circular read: “Gray Maltese cat. Collar bearing his name, Snooperkatz. A reward of $1 will be paid for his safe return to Gudebrod Bros., 644 Broadway.”

Snooperkatz apparently was in the habit of visiting a black female cat across the street at the Bleecker Street Savings Bank, so Christian was hoping someone would find his cat there and return it to him for the $1 reward.

Unfortunately, nobody returned Snooperkatz. However, every man, woman, and child who saw the flyer brought Christian Gudebrod multiple street cats in hopes of getting the dollar reward.

As The Sun reported on May 11, 1894, within just a few days, the large building was overrun with cats, “raising their voices in a stream of profanity that is dark, deep and strong.” There were “black cats, white cats, gray cats, yellow cats, mottled cats, tomcats, pussy cats, tailless cats, earless cats, whiskerless cats, cats of high caste, and cats of absolutely no caste at all!”

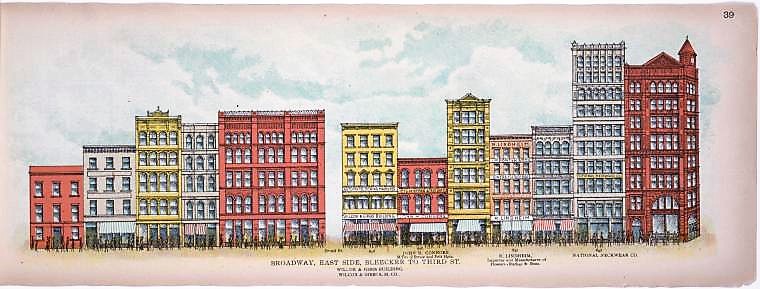

Snooperkatz made his home in Christian Gudebrod’s offices at 644 Broadway and Bleecker Street (on the far right in this 1899 illustration), an eight-story, Lake Superior orange sandstone and Columbus brick building designed by Stephen Decatur Hatch in 1891 for the Manhattan Savings Institution.

Two weeks after Snooperkatz disappeared, Christian sat down with a reporter from The Sun to talk about his favorite cat. “Oh sir, unless you are a lover of cats you can have no idea how I feel about Snooperkatz. There was only one cat in the world like him, and he’s now dead.”

“Have a cigar?” he asked the reporter as he tossed a paperweight at yet another stray cat while telling the man how much he adored his lost Snooperkatz.

According to Christian, Snooperkatz was quite intelligent, but he didn’t have a lovable disposition. He was always up to mischief and could never be trusted. But still, he said, he became very attached to him and overlooked many of his faults.

This 1895 photo of the west side of Broadway, just north of Bleecker Street, was probably taken from inside 644 Broadway. This would have been Snooperkatz’ view when he was the office cat for the Gudebrod Silk Company. New York Public Library Digital Collections

Snooperkatz was a very beautiful cat, but he was also a thief and quite wicked. According to Christian—I’m not sure if he was telling a tall tale or not—somehow the cat learned how to steal postage stamps from his desk and bring them to the milkman to “buy” milk for himself. “Heaven knows where he learned the trick, but he did it every morning,” he said, noting he found out about the trick from the building’s janitor, who witnessed it every day.

As the story goes, as soon as Snooperkatz heard the milk wagon rattling down the street he would pull out the little drawer where Christian kept his stamps, lick up 5 or 10 cents worth, and run down the stairs to the milkman.

One time the office cat tried to steal a spool of silk thread by swallowing it. The thread was rescued by tying one end of it to a revolving spindle. The spool itself, Christian explained, “had to go through the process of digestion.”

Snooperkatz also learned how to steal the elevator boy’s lunch. According to Christian, he would climb up the screen door of the elevator and push the button. As soon as he saw the elevator coming up he would run down the stairs and take the boy’s lunch.

In addition to tricks, Snooperkatz also had a keen sense of right and wrong. For example, one day Christian reprimanded a customer for trying to submit a bill in person rather than by mail. The next time the man came to the office, the cat sprang upon his back, knocked his hat off, and buried his claws in the man’s head. Since that day, the man always sent his bill by mail. (Can you blame him?)

Today, 644 Broadway looks very much as it did in 1894, when Snooperkatz went missing from Christian Gudebrod’s office.

“Snooperkatz was a valuable cat,” he told the reporter after sharing his story about the customer. “I became strongly attached to that cat and when he disappeared I cannot tell you how grieved I felt,” Christian said. “What endeared Snooperkatz to our firm more than any of his other wonderful habits was his sympathetic nature.”

In addition to Snooperkatz, Christian also had a cat named Tom Toots, who spent most of his time at Christian’s home. Tom was reportedly quite the gymnast and delighted in performing tricks. He especially loved playing on the swing that Christian had rigged up in the apartment window.

Unfortunately, as Christian told the reporter, the swing caused the death of Tom. Apparently a careless servant once left a glass of whisky on the table. Tom Toots knocked it over and lapped up the whisky. He then jumped up into the swing, lost his balance, and fell to the street.

As Christian told the story to the reporter, his voice got very husky with emotion. He cleared his throat and finished his cat tale. “Snooperkatz was more intelligent but he didn’t have Tom’s lovable disposition.”

A Brief History of 644 Broadway

The land on which the large building at 644 Broadway was constructed in 1891 was formerly part of the 160-acre Anthony Lispenard Bleecker farm. Bleecker, a prominent banker, merchant, and auctioneer, and a vestryman and warden for Trinity Church, purchased the land in 1790 from the trustees of Stephen H. Bayard, whose large farm was split in 1775 when Great George Street (Broadway) was cut through the property.

According to an article in The New York Times published on April 28, 1889. Bleecker paid 2,350 pounds (Colonial currency) for the lots at 644 and 646 Broadway. He sold the lots to Gordon L. Mumford for $3,850 in 1812. George Lorillard bought the land in 1821, paying about $5,500 for the two Broadway lots.

This illustration depicts the junction of Broadway and Bleecker Street in 1820, just 70 years before the Manhattan Savings Institution building at 644 Broadway was built. NYPL Digital Collections

In the 1830s, Lorillard built a large peaked-roof house on the Broadway lots, which were then numbered 644, 644 1/2 and 646. The ground floor of the building had three stores: Dr. Jefferson B. Nones had a drug store, John and William Blackett dealt in hardware, and William Randoll had a barroom.

Upstairs were meeting rooms for the Andrew Jackson party, and when the Fifteenth Ward was created, the Democrats of the district held their meetings in Randoll’s barroom. Across the street at this time, on the southeast corner of Broadway and Bleecker, was the mansion of John Mason, president of the Chemical Bank.

George Lorillard died in 1832, leaving a complex will that created a family litigation mess for his brothers Jacob and Peter Lorillard (of tobacco and Tuxedo Park fame), their children and spouses, his niece and nephews, and several other members of the extended family.

Eventually, George’s niece and husband, Robert Bartow, received a portion of the estate, which included the peaked-roof house at 644-646 Broadway. Blaze Lorillard Jr. inherited 69 Bleecker Street and a murky alley adjacent to the lot, and George Lorillard got 71 Bleecker Street. Blaze closed off the alley and built his house on this land, which was numbered 67 Bleecker Street.

In 1854, Robert Bartow demolished the old peaked-roof house on Broadway. He built a new structure on the site, which was leased by the Manhattan Savings Institution in 1855.

Over the years, the old Lorillard dwellings on Bleecker Street were acquired by William Garrard, an Englishman and former steward on the New Orleans and Havana steamer De Soto. Garrard opened a chop shop at 71 Bleecker–which he called De Soto’s–in 1861. Customers reportedly waited in line for his specialty chops, port wine, brandy, and English ale. To accommodate his growing customer based, he leased 67 and 69 Bleecker Street in 1863.

The Manhattan Savings Institution

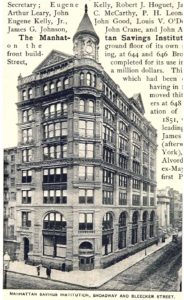

The Manhattan Savings Institution at 644 Broadway, northeast corner of Bleecker St.

The Manhattan Savings Institution (MSI), later the Manhattan Savings Bank, was founded in 1850 and opened in 1851 at a building that stood at 648 Broadway. In 1855, the bank leased the new Bartow building at 644-646 Broadway, which it later purchased in 1863.

In 1888, MSI bought the adjoining property occupied by De Soto’s chop house at 67-71 Bleecker Street. De Soto’s and the old bank building were razed to make room for the eight-story, fire-proof building that still stands today.

In 1942, MSI, the Metropolitan Savings Bank, and the Citizens Savings Bank merged, forming the Manhattan Savings Bank. That year, the bank closed its branch at 644-646 Broadway. The upper floors continued to house small manufacturers until the 1970s, when they were converted to residential lofts.

The building was converted in 1987 to a residential cooperative with 15 luxury loft apartments. It was registered as a New York landmark in 1999 and is now called Bleecker Tower.

The MSI is still clearly visible on the old Manhattan Savings Institution building at 644 Broadway.

Wow, great article! Oddly enough, a few weeks ago, on International Cat Day, I posted to my group, Costume People to celebrate our shop cats by sharing their photos. Costume shops often have cats & sometimes dogs in residence, so needless to say, I loved this post. Also I’ve been preparing a post, inspired by a walk I took in the East Village that will highlight the block surrounded by Bond, Bowery, Bleecker & Broadway which includes the Manhattan Savings Institution, so I have already done a little research on this building! You have filled in some interesting details.

So glad you enjoyed it! Do you have a photo of your shop cats? I’d love to come visit you and your cats one day when I’m working in the city. Where is your shop?

While researching the elaborate houses made for the sparrows of Union Square Park in the 1860’s, I came upon your site and this delightful and informative article. Both have made my day! History (especially New York history) + interesting animal stories — I am now a loyal reader! Thanks for this amazing little spot on the internet!

I am always happy to hear when someone has discovered my site — so glad you enjoy the stories! I’ve been doing this for almost 5 years now, so I have quite few tales, and I’m currently compiling many of my cat stories into a book, so stay tuned and thank you again.