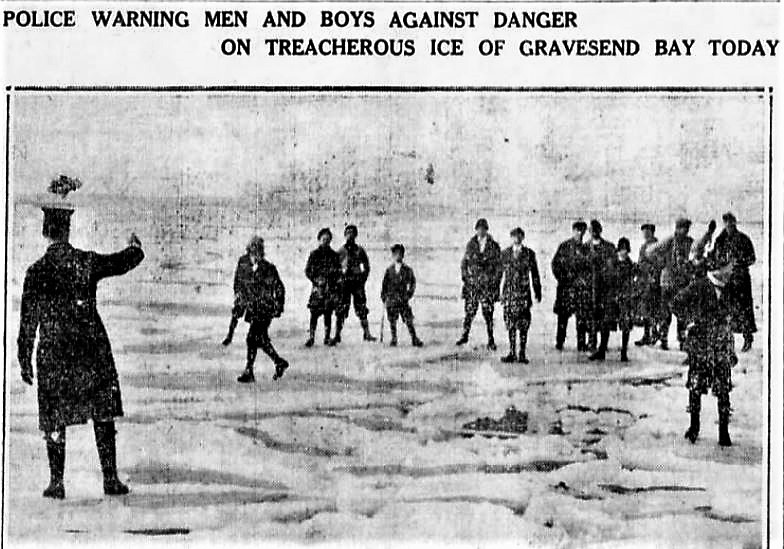

In February 1912, ice floes filled the Gravesend Bay and the Narrows, making it possible for hundreds of adventurous people to cross the bay to Norton’s Point on Coney Island. It was the first time since the great blizzard of 1888 that the waters froze enough to form an ice bridge made of giant ice floes.

NBC’s Katie Couric struck a nerve with the Dutch during the Pyeonchang Olympic Opening Ceremonies by saying the reason the Netherlands is so dominant in speed skating is because “skating is an important mode of transportation” for the people of Amsterdam when the canals freeze over.

There was quite a lot of backlash from the viewers, who pointed out correctly that not only do the canals rarely completely freeze over, but the Dutch usually get around like everyone else in the world, either by foot, bicycle, or car. Oh, and they also don’t wear wooden shoes anymore.

To be sure, there have been winters that were cold enough to turn Amsterdam’s canals into frozen skateways, but for the most part, the Dutch mostly rely on man-made ice skating rinks or frozen ponds for their skating pleasure.

New York City hasn’t had a canal system since the British filled in the canals of the city’s early Dutch settlement in 1676 (and the old canal that is now Canal Street was covered over in 1819), but the city is surrounded by water. And that water has frozen over several times in the past, most notably in the 1800s and early 1900s, before our winters got warmer and the shipping traffic got heavier.

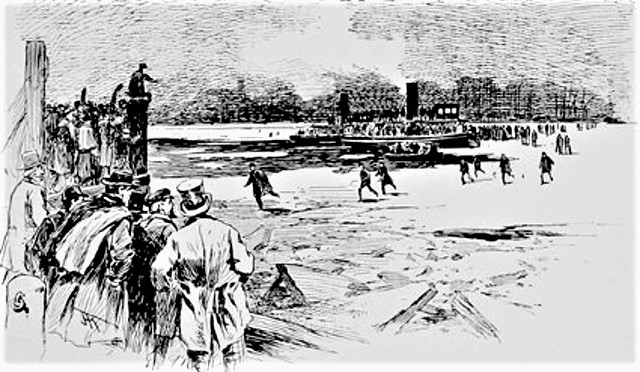

The East River froze over several times in the 1800s, allowing people to cross between Manhattan and Brooklyn by jumping from one ice floe to another.

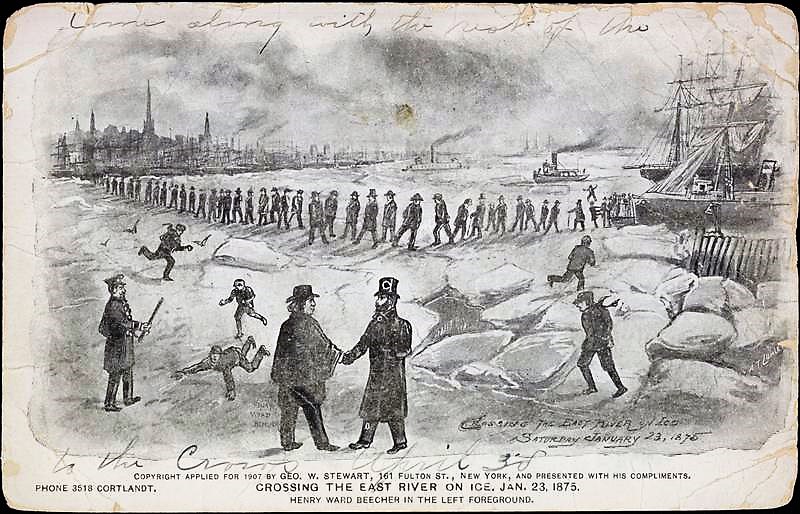

For example, during the winters of 1821, 1851, 1856, 1857, 1867, 1875, and 1888, the East River froze over, creating an “ice bridge” between Manhattan and Brooklyn that was used by thousands of people and horses to cross between the two boroughs. In fact, after the ferries shut down due to ice in 1867, and about 5,000 people had to cross over the ice bridge, it was decided that a permanent bridge was necessary. Hence, the idea for the Brooklyn Bridge was born.

The Winter of 1912

In February 1912, during a record-breaking cold spell that affected the entire country east of the Rocky Mountains, the waters of Gravesend Bay and the Narrows froze over for the first time since New York City’s notorious blizzard of 1888. Huge blocks of ice piled upon the shores of the New York Harbor, creating havoc with the ferry service and making the Long Island Sound entrance to the East River all but impassable.

On February 11, a throng of about 300 men, women, and children who had ventured out onto the frozen Gravesend Bay in Brooklyn watched in horror as a huge block of ice separated itself from the frozen ice field and floated away toward the unfrozen section of the bay. Eighteen-year-old John Gibbon of 1907 Benson Avenue and 17-year-old Robert Diamond of 8792 Nineteenth Avenue clung to the ice as it moved into dangerous territory.

About 5,000 people reportedly crossed the frozen East River between Manhattan and Brooklyn when it froze over on January 23, 1867.

The young men, apparently sensing an amazing adventure, began jumping from one cake of ice to another in their attempt to make it back to the solid field of ice. The men and women shouted out words of encouragement as the boys make one successful leap after another.

On the shore, fishermen Hank Twiner and James Thompson of Ulmer Park grabbed a boathook and whistled to Jack, Hank’s Newfoundland dog. The crowd cheered as the men and their dog made their way further out onto the thin ice, Jack running ahead without fear and the men testing each step with the boathook.

Renowned preacher and abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher, who founded the Plymouth Church in Brooklyn in 1847, is shown (left, foreground) standing on the frozen East River on January 23, 1875.

When the thin ice halted their progress, Jack and the fishermen also took their chances at leaping from one ice floe to another to get closer to the stranded boys. The lads, overanxious now that help was so near, tried to leap one more time. They missed and landed in the icy cold water.

Jack immediately jumped into the water on instinct and held the boys afloat while the men used their boathook to drag the lads and the dog back onto the floating ice cake. They dragged themselves closer to the ice field and, with one more leap, they all landed safely on the frozen ice and began running toward shore.

The fishermen hustled the boys into a drugstore, where Dr. Overend came by ambulance from the Coney Island Hospital and treated them. When their clothing was fully dried, the young men returned home to continue recovering. Hopefully, Jack was also treated and rewarded for his heroics with a large bone.

Four Years Earlier…

Coincidentally, exactly four years earlier, on February 11, 1908, a Newfoundland named Nero came to the rescue of his master, Edward Neary, when the Wall Street executive broke through the ice while walking across the frozen Gravesend Bay.

The dog was reportedly on land when he saw Neary fall through about 70 yards from the shore. He ran toward his master and sunk his teeth into his sweater to hold him afloat.

At the time, about 50 residents of Bath Beach were walking on the ice from Ulmer Park to Fort Hamilton. They all froze in terror as they watched Neary, burdened by rubber boots and heavy clothing, disappear under the surface of the water. The Newfoundland held onto his unconscious master until some other ice walkers sprung into action and grabbed a plank to help pull him to shore.

Neary was taken home in precarious condition. Nero was reportedly rewarded with juicy morsels of meat and a new straw bed to sleep on that night.

Once again, a marvelous post. I so enjoy your blog!