This quirky lobster tale of Old New York begins on a Sunday night in May 1910 when Gus, a brindle bulldog, walked into Fay’s restaurant at 255 West 125th Street in Harlem around 7 p.m. and sat down for dinner with his master. Gus was reportedly well behaved, so he was allowed to sit with his owner, Miss Rose Leland of 516 West 179th Street, as long as his leash was wrapped around her chair while they both ate their dinners.

Outside on the sidewalk was an icebox, where live lobsters were kept. Whenever one of Fay’s customers ordered lobster, the waiter would grab a few and let the customer choose which one he or she wanted.

This icebox was of great interest to Mattie, one of Fay’s several restaurant cats. She spent most of her time not performing her mousing duties, but staring intently at the curious creatures in the icebox.

On this particular spring night, one of the lobsters fell on the sidewalk after the waiter had gone inside. Naturally, Mattie jumped at the opportunity. She had no idea what she was up against.

The lobster clamped its claw onto Mattie’s tail, sending her howling and scurrying through the front door and into the restaurant. Not about to be left out of the fun, Gus the bulldog pulled wildly at his leash–and Miss Leland’s chair–to join in the melee.

Down went Miss Leland, who screamed in horror and then reportedly fainted. Gus caught up with cat and lobster as they ran around the other diners. The lobster released its claw on Mattie and grabbed Gus by the hind leg.

The waiters were finally able to break up the ruckus and tie Gus up behind the cashier’s desk. Mattie was then locked in the kitchen. The New York Times reported that “it may be said that the lobster received the proper burial.”

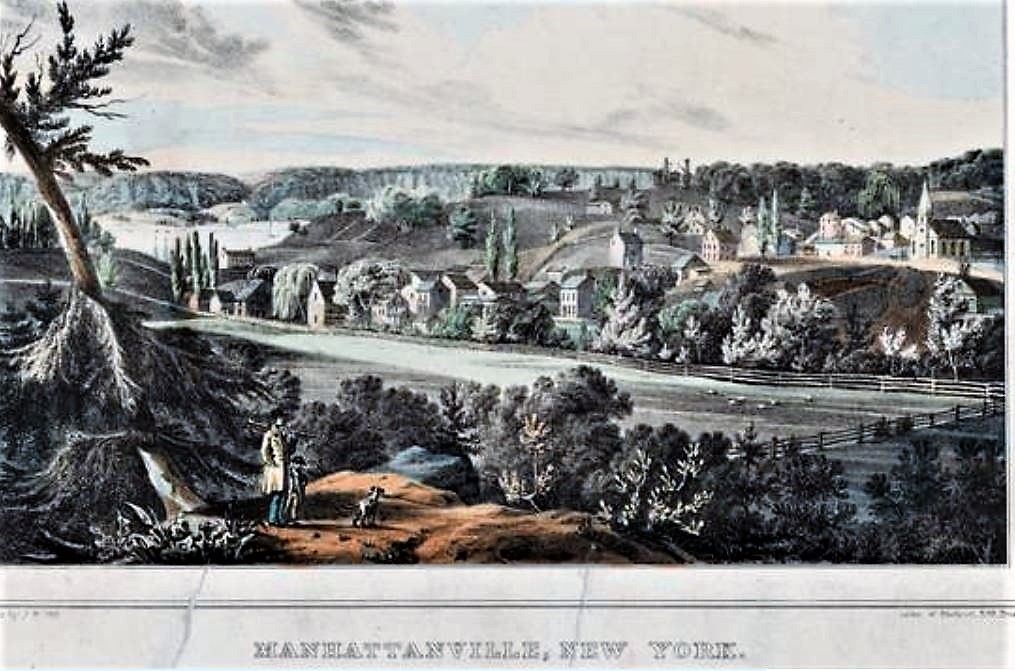

The Manhattan Valley

This story takes place in what was one of the first areas of Manhattan to be settled after Henry Hudson discovered the New World. With its sandy beach and gently sloped valley that allowed easy entry between the shoreline bluffs and the interior, the area that we now know as Harlem was the ideal location for a settlement. The valley, which the Dutch called the “Hollow Way,” is now the area around West 125th Street.

In 1658, the Dutch established the village of Nieuw Haarlem along the Harlem River at present-day East 125th Street. By 1703, there were two main thoroughfares into Nieuw Haarlem: Manhattan Street (now 125th Street), which followed the geological fault line, and the Bloomingdale Road (Broadway), which followed an old Native American trail that meandered up the length of the island, and which connected the village with New York (so named after the British took over in 1664) in Lower Manhattan.

One of the earliest settlers in this area was a Quaker named William Lawrence, who established a farm centered around what was then called Manhattan Street. The property passed to his son John and his wife, Anna Burling, following William’s death in 1680, and later to their daughter, Hannah Lawrence.

Hannah was a poetess who risked her life and safety when she left leaflets throughout Manhattan with her penned verses that contained thinly veiled protests against the occupation of the British army during the Revolutionary War. Although she deplored the conduct of the British soldiers, she fell in love with a British solider named Jacob Schieffelin, who was staying at her family’s house.

Shortly after Hannah and Jacob married, the couple headed for Canada for the duration of the war. When the war ended, they returned to New York, where Jacob went into the drugstore business with Hannah’s brother. Jacob and Hannah’s brothers laid out a village in the vicinity of today’s 125th Street and Broadway, which they called Manhattanville.

In 1823, through monetary and property donations, Jacob and Hannah Schieffelin established Saint Mary’s Church on Lawrence Street (near 129th Street, east of Broadway), the first free Episcopal church in America.

Although the original wooden church was razed in the early 1900s, it was replaced with the present neo-Gothic structure at 521 West 126th Street built from 1908-09. The gabled-roof porch contains a bell that was presented to St. Mary’s by Jacob Schieffelin. Under the side porch of the church is the burial vault of the Schieffelin family.

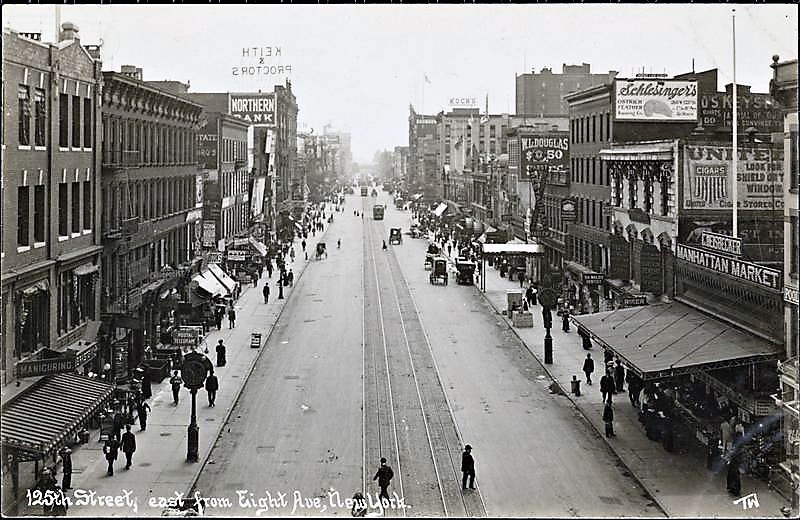

253-259 West 125th Street

Fay’s restaurant was located at 255 West 125th Street. In the late 1800s, 255 and 253 were frame buildings with large back yards. In 1895, Sarah R. King had a stationery store at 255, and Mr. Leslie H. Crouch had a real estate business in the building. Next door at 253, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle had a branch office.

On June 23, 1912, the New York Times announced that a new theater was being built for Benjamin Hurtig and Harry Seamon on West 125th Street. At the time, Hurtig and Seamon had been occupying the old Harlem Opera House erected by Oscar Hammerstein in 1889 just down the block at 211 West 125th Street.

The land on which the new theater was was planned was held by Felix Isman under lease through the Sonn Brothers. Isman sold the lease to Philadelphia dry good merchants Jacob D. and Samuel D. Lit in April 1911, who in turned leased the land to Charles J. Stumpf and Henry J. Langhoff–popular Western clothing outfitters from Milwaukee, Wisconsin–for 99 years. Sumpf and Langhoff in turn sold a 30-year lease to Hurtig and Seamon.

In a transaction negotiated by Sidney S. Cohen, Hurtig and Seamon arranged to build a theater occupying 125th and 126th Streets. A 75 x 100, three-story building having an entrance to the theater proper was constructed at 253 to 259 West 125th Street, and the theater itself was built on a 100 x 100 foot lot at 240 to 260 West 126th Street.

Hurtig and Seamon agreed to pay an annual rental of $40,000 for the first ten years, $42,500 for the next ten years, and $45,000 for the last ten years. Work began in May 1913, and Hurtig and Seamon’s New Burlesque Theater opened in 1914. Like many other American theaters during this period, African-Americans were not allowed to patronize this new Harlem theater or perform there.

In 1933, following a campaign by Fiorello La Guardia to shut down burlesque houses, Hurtig and Seamon’s closed down. Cohen reopened the theater as the 125th Street Apollo Theatre in 1934 with his partner, Morris Sussman, and changed the format to variety revues. Cohen and Sussman focused their marketing on Harlem’s growing African-American community.

Today, where 100 years ago a cat and dog went paw to claw with a lobster, the legendary Apollo Theater presents concerts, performing arts, and educational and community outreach programs. And just next door, a new restaurant has opened its doors to serve theater-goers. I got a good laugh when I saw this on Google Streets — I think you will too.

.

Great story, must have been hilarious!

Glad you enjoyed it! The health department wasn’t so active back then, so I’m sure many incidents involving restaurant cats and dogs took place in Old New York.