Brownie Gavan lived at 3033 Godwin Terrace in the Kingsbridge section of the Bronx from about 1942 to 1954. He was the beloved pet of my father, Roger Gavan.

Happy Fathers’ Day, Dad! This story is for you. I hope you enjoy reading about the fascinating history of your childhood home.

(To my regular readers: The following story is quite long, but it is a gift to my father, so I put a lot of time and content into it. I hope you get a chance to read it all when you have the time.)

3033 Godwin Terrace, 1929

In July 1929, Mrs. Catherine Kirschoff was murdered in her bathroom during a robbery at her apartment in the brand-new apartment building at 3033 Godwin Terrace in the Kingsbridge section of the Bronx. Her husband Fred discovered her fully-clothed body in the bathtub. A large rope hung from her neck.

Mrs. Catherine Kirschoff, 55, was murdered in at 3033 Godwin Terrace in 1929.

Police first ruled it a suicide, but after discovering numerous bruises on her body, and learning that several pieces of jewelry, including two diamond rings, were missing, they confirmed she had been strangled to death during a robbery gone very bad.

A few residents told police they had seen a man going door-to-door and asking residents if they wanted their windows washed. Several descriptions of the man were broadcast, but he was never apprehended.

Fifteen years later, in 1944, another person (or perhaps persons) tried to burglarize a top-floor rear apartment at 3033 Godwin Terrace. The burglars were not successful.

They were scared away by Brownie Gavan’s loud barks from the fire escape before they could cause any real damage or steal anything from the apartment building where my dad, Roger, lived with my grandparents John and Virginia Gavan.

Brownie Moves to the Bronx

A boy and his dog: My dad with Brownie, probably somewhere in the Riverdale section of the Bronx.

Brownie joined the Gavan family sometime around 1940, when he was just a puppy. My grandfather, who drove a city bus, found the dog on his route and brought him back to their apartment at 9 Cabrini Boulevard in the Washington Heights section of Manhattan.

My dad often took Brownie up to Riverdale, where there were still lots of undeveloped fields to run in and explore.

When my father was about six years old, the Gavans moved to a top-floor, one-bedroom walk-up apartment in the five-story New-Law (dumbbell-shaped) building at 3033 Godwin Terrace, just up from West 230th Street. Brownie quickly became the canine squire of the Kingsbridge neighborhood, most often walking with my dad up and down the hilly streets without a leash.

On the rare occasions that he ran off to explore his kingdom on his own, Brownie woulud always return and wait for my dad on the stoop. (Only once did he fail to return in a timely manner; that day my dad attended mass five times to pray for his safe return. Either the prayers worked, or Brownie just got tired and hungry.)

When Brownie was younger, my father would take him to the Riverdale section of the Bronx, where, in those days, there were still plenty of vacant fields and woodlands. As he and my dad both got older, he was often relegated to the rooftop to get his exercise and do his business.

Brownie’s Final Home

As we all know, pets can bring us so much joy in life, but their lifetimes are way too short. If we’re lucky, they pass in our presence, allowing us to look into their eyes and tell them how much we love them as they quietly slip away. But sometimes they simply run away, and we’re left to agonize over what may have happened to them.

My father appeared in the Riverdale Press while attending Manhattan College and preparing for a career in the U.S. Air Force.

For Brownie, sadly, it was the latter. On his last day with my dad, he had traveled with my father and his friend to a field in Putnam County, New York. My dad had just turned 18, and he was anxious to go target shooting in the country. The sounds of the guns probably frightened the older dog, and he ran away.

My dad on the rooftop of 3033 Godwin Terrace, sometime around 1946. When I was a young girl, I also enjoyed going up on the roof and looking at the world around me.

My dad and his friend spent hours looking for Brownie, but he returned to the Bronx that night with only memories of his four-legged best friend. To this day, he hopes that some kind stranger found the dog and provided him with a good home in the country to spend his final years.

To this day, he also believes in letting his pet dogs–like Odie and Rocket, who have both passed–run free without a leash on his property in Warwick, New York. Never once did they run away from home. And they always reminded him of Brownie.

An Extended History of Kingsbridge and The King’s Bridge

“The time is now at hand which must probably determine whether Americans are to be freemen or slaves.”–General George Washington, before the Battle of Long Island on August 26, 1776

In the summer of 1776, General George Washington sent Major General Charles Lee to New York to prepare its defenses against the British. In addition to establishing a defensive post at Brooklyn Heights, Lee also believed that the King’s Bridge, which connected Manhattan with the Bronx, should be defended to prevent the British from cutting off a primary route for Americans escaping New York City.

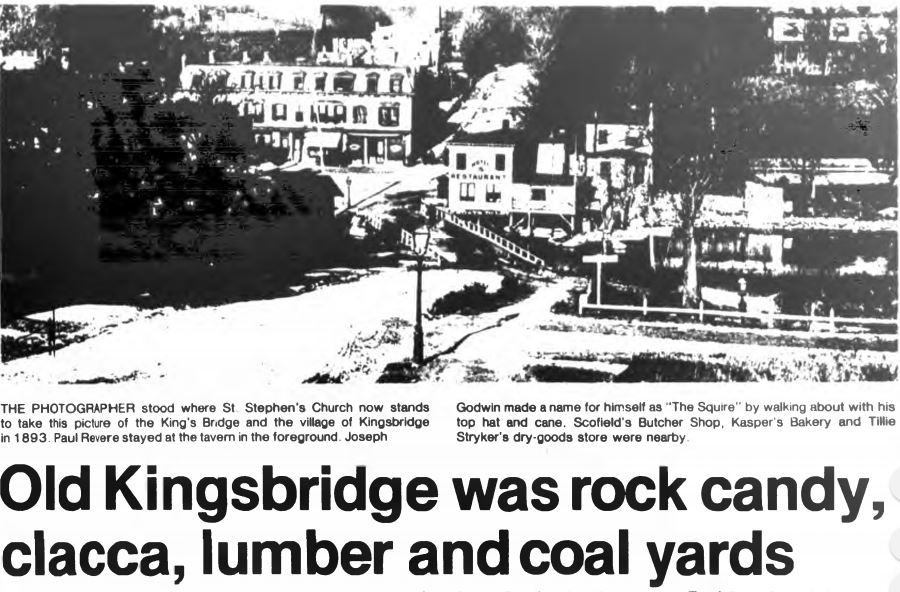

During the Revolutionary War, the area we now know as Kingsbridge was the site of many American and British forts and battles. Paul Revere reportedly passed through and stayed overnight during one of his rides. It was also where Washington had his temporary headquarters for a few days, and where he called a meeting of general officers on October 16, 1776, when it was determined to abandon Manhattan. (The American army lost the bridge in a fierce battle with Wilheim von Knyphausen’s Hessians.)

There is much written about Kingsbridge during the Revolutionary War, so I’m not going to get into the details here. There’s a great book written by Thomas H. Edsall in 1887 that is available for free online. I highly recommend if you’re interested in taking a deeper dive.

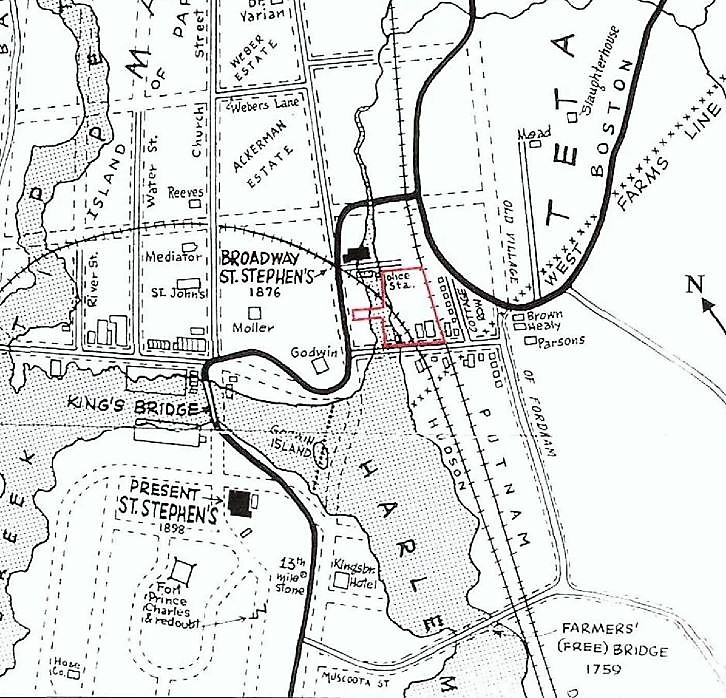

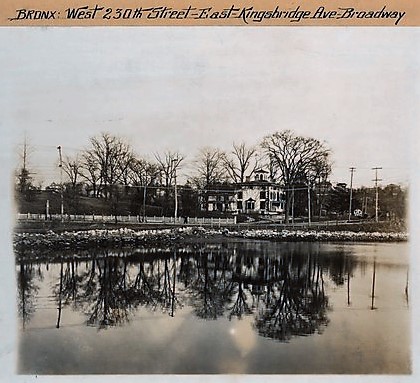

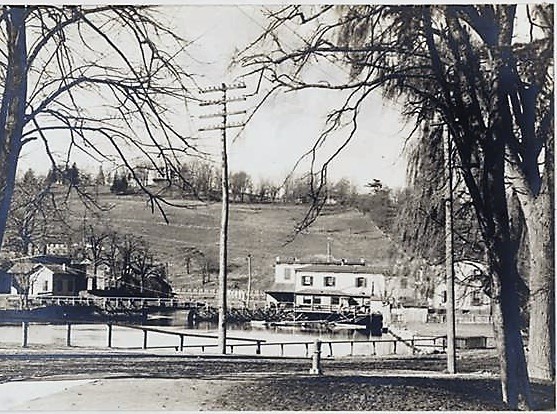

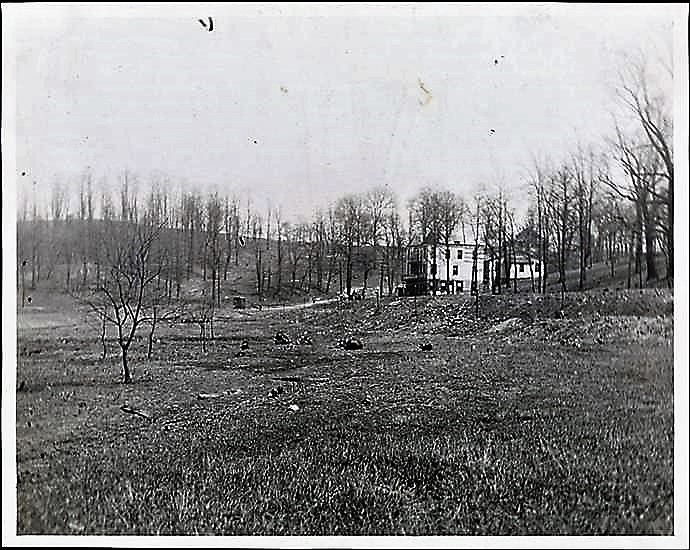

The point that I want to emphasize for this story is that a lot of important American history place near the old King’s Bridge, on what would later become the Joseph H. Godwin estate, bounded by present-day Marble Hill (the old Jacob Hyatt estate and marble quarry), West 231st Street, Kingsbridge Avenue, and Bailey Avenue.

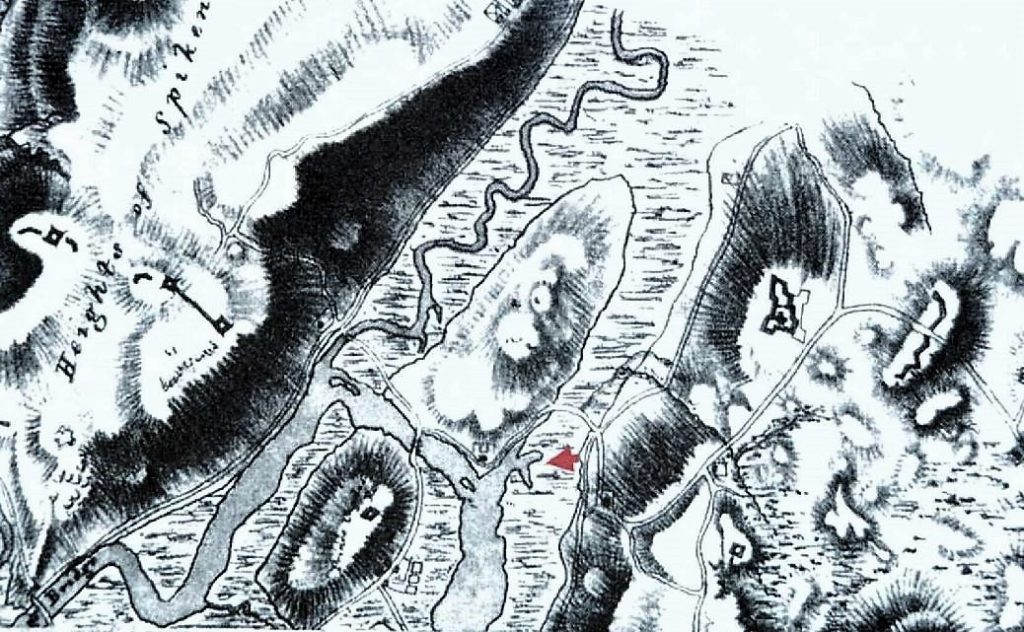

In this 1782 British army map, Kingsbridge–then called Paparinamin–is depicted by the hillside north of the river (the red arrow marks the location of today’s Broadway and West 230th Street). Marble Hill is south of the river, in Manhattan. Notice the old King’s Bridge and the small “island” between the two hills. Some of the forts are also noted on this map, including Fort Prince Charles on top of Marble Hill.

Here’s an aerial view of Kingsbridge and Marble Hill today. Notice that although the waterway separating Marble Hill and Kingsbridge was filled in 100 years ago, West 230th Street and the streets of Marble Hill still follow the curve of the former hill and waterway shown on the army map above. (Today’s Spuyten Duyvil Creek is the old Harlem Ship Canal, which opened in 1895.)

The Islands of Kingsbridge and Marble Hill

In the colonial era, depending on the season or water levels, Kingsbridge was either an island or a hill (about 40 feet in elevation) called Paparinamin by the Weckquasgeek Indians. Prior to the excavation of the Harlem Ship Canal at 225th Street in 1895 (which turned Marble Hill into an island for about 20 years), Marble Hill and the estate of Jacob Hyatt was the northern boundary of Manhattan.

The waters separating Marble Hill from Kingsbridge flowed along the south side of 230th Street under the site of today’s Marble Hill Housing Project to present-day Kingsbridge Avenue and then southwest into the Hudson River. East of the King’s Bridge it was called the Harlem River. West of the bridge it was called Spuyten Duyvil Creek (sometimes written as Spiting Devil on old maps) .

The creek west of the King’s Bridge was filled in from 1894 to 1895. The river east of the bridge was filled in from about 1914 to 1917 (the fill included rocks excavated for the foundation of Grand Central Terminal). After the waterway was filled in, West 230th Street was no longer the southern terminus of the Bronx, and Marble Hill was no longer an island.

Verveelen’s Ferry

Before we go any farther, let’s go back about 350 years to 1669, when Johannes Verveelen and his son Daniel were authorized by Governor Francis Lovelace to operate a ferry near the “wading place,” a small sandbar in the middle of the Harlem River that was visible at low tide. (The sandbar was opposite present-day Broadway.)

The new ferry allowed Governor Lovelace to collect a fee from the farmers and cattle drovers who had previously used the sandbar to cross between the mainland and Manhattan. (The only other crossing was another ferry at present-day East 125th Street, which connected the mainland to Niew Haarlem.)

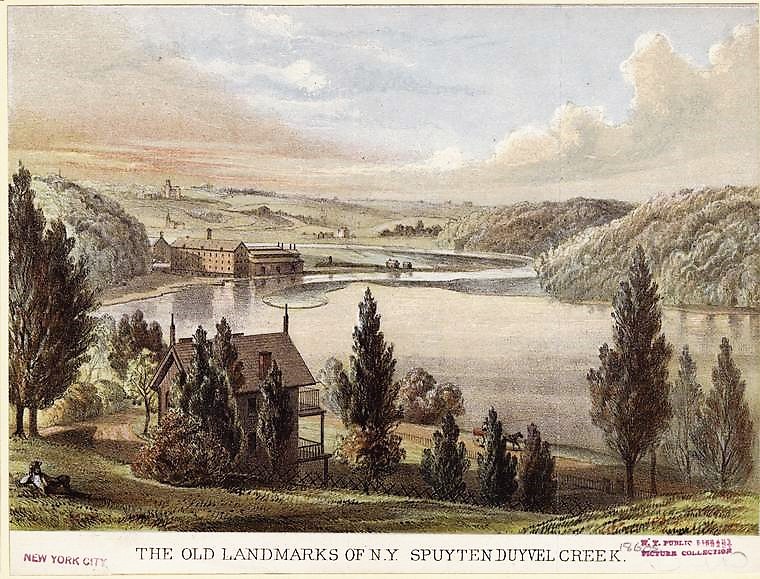

I wonder if the man at left admiring the view is Jacob Hyatt, the northern-most resident of Manhattan before the Spuyten Duvil Creek and Harlem River were filled in. The large building at left is Alexander Macomb’s grist mill, which came down in 1856. (Notice the horse and carriage between the trees.)

In addition to the ferry, Verveelen was also directed to “erect a good dwelling house on the island or neck of land…where he was to be furnished with three or four good beds for the entertainment of strangers, and also with provisions at all seasons for them, their horses and cattle, together with stabling.” The exact location of the inn is uncertain, but it was probably near the foot of present-day Broadway or Godwin Terrace and West 230th Street.

Old records indicate that for lodging any person at his inn, Verveelen charged eight pence per night “in case they have a bed with sheets, and without sheets 2 pence in silver.” It cost seven pence in silver to transport a horse and a man via the ferry, and six pence for a single horse or head of cattle. (You can see why a farmer or cattle drover would have preferred to wade across the water.)

Verveelen retired from the ferry and roadside inn business in 1693. He passed away in 1702.

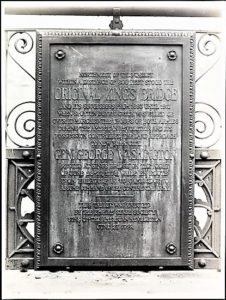

The southern terminus of the old King’s Bridge is marked by a tablet on St. Stephen’s Methodist Episcopal Church at West 228 Street and Marble Hill Avenue. A plaque commemorating the northern end of the bridge is on the southwest corner of Broadway and West 230th Street.

The King’s Bridge and General Macomb

In 1693, when Colonel Frederick Philipse of Yonkers secured his patent for the Manor of Philipsburgh, Governor Benjamin Fletcher instructed him to build a bridge to replace the ferry. In honor of King William III (William of Orange), it was called the “King’s Bridge.”

The bridge originally stood near present-day Broadway, but in 1713 it was moved further west, crossing the creek from the foot of Marble Hill to today’s Kingsbridge Avenue and West 230th Street.

During the war, Verveelen’s inn was taken over by Philipse’s gardener, a Tory named John Cox. Inside the inn, Cox reportedly hid the head from a lead statue of King George III on horseback, which had been knocked over in Bowling Green by American patriots on July 9, 1776. (Back then, we really didn’t like the idea of a king ruling our country, and we weren’t afraid to take action.)

At some point the statue’s head was transported to London “in order to convince them at home of the infamous disposition of the ungrateful people of this distressed country.”

After the war, the Paparinamin tract was sold by the Commissioners of Forfeiture to Daniel Barkins, Abraham Lent Jr., and inn-keeper Joseph Crook (the deed was dated July 30, 1785). Over the next decade, the old Verveelen inn and surrounding property was owned by numerous men, including brewer and farmer Medcef Eden, merchants John Ramsey and Alexander von Pfister, inn keeper Daniel Halsey, and Joseph Eden.

General Alexander Macomb purchased nearly one hundred acres in the Kingsbridge area.

In 1797, General Alexander Macomb, a wealthy fur trader and major general in the U.S. Army, purchased the property and built a square, stone and brick mansion near the bridge (the mansion reportedly incorporated some of the old stone walls of Verveelen’s tavern). He surrounded the mansion with gardens, shrubberies, elm trees, and walkways.

During the next five years, Macomb bought many adjoining parcels–mostly salt meadow–making up about 100 acres bounded north by Van Cortlandt (West 240th Street), east by the old Albany post road (Broadway/U.S. Route 9), south by the Harlem River and Spuyten Duyvil Creek, and west by Tippett’s Brook (Tibbett Avenue). He renamed Paparinamin “Island Farm” or “The Island.”

Macomb planted a great variety of fruit trees on his island farm, and, according to one report, “its fertile soil made it one of the most valuable estates near the city.”

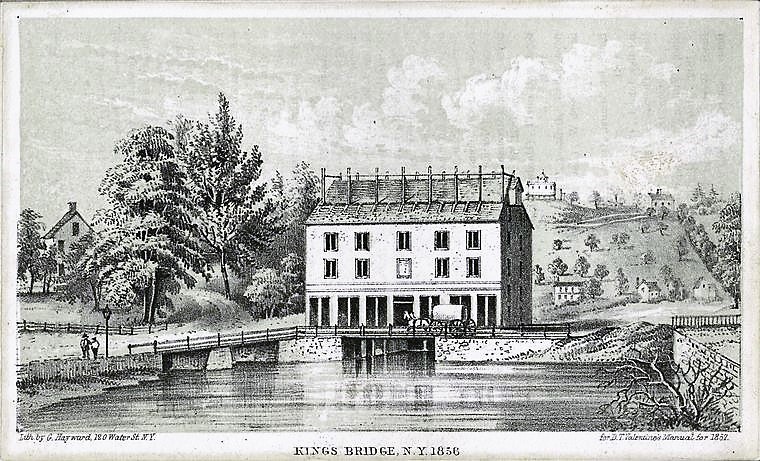

The King’s Bridge as it looked in 1856. Notice the hilly area in the background — today we know this as Broadway, Kingsbridge Avenue, and Godwin Terrace. The white house on top of the hill may be the Moller mansion, which I write about later in this story.

Here’s another view of the old King’s Bridge from the early nineteenth century.

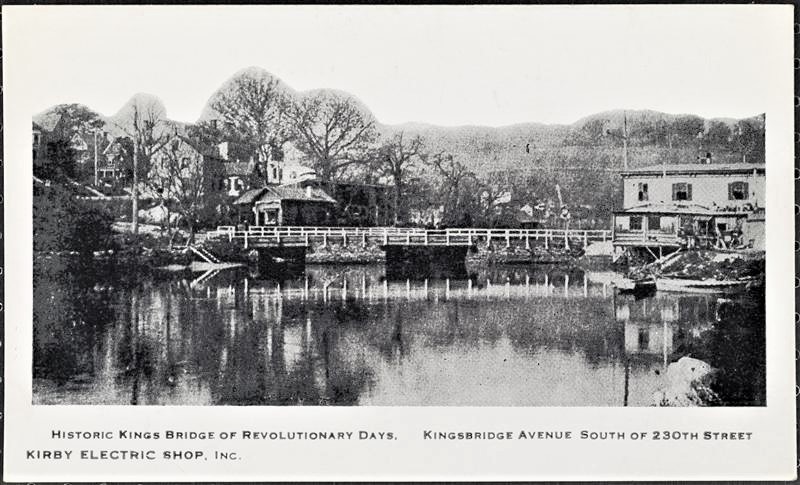

This view of the King’s Bridge is looking south on Marble Hill Avenue toward Marble Hill in 1906. St. Stephen’s United Methodist Church (extant) is in the background, on the left.

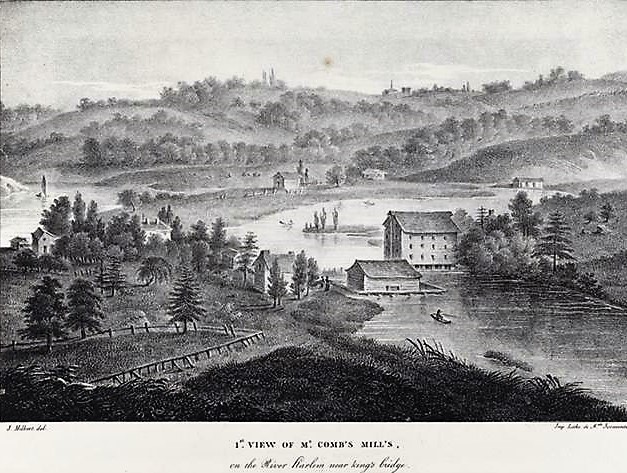

In December 1800, Macomb secured a water grant extending across the creek, just east of the King’s Bridge, allowing him to erect a $30,000, four-story frame grist mill that was capable of grinding 1,000 bushels of grain per day. Sadly, Macomb’s mill was a failure, and his extensive real estate ventures also proved disastrous. In 1810, the Paparinamin tract and the mill were sold under foreclosure to his son Robert.

In 1830, Robert’s wife, Mary C. P. Macomb, acquired the Paparinamin tract and moved into the old stone house. She loved entertaining her many guests; Edgar Allan Poe, who lived in nearby Fordham with his wife, Virginia, and his cat, Caterina, was a frequent visitor.

By 1847, Mrs. Macomb had laid out the estate into streets and plots for sale. Over the next few years, several houses were erected, as well as a few stores and shops, three churches, and a grammar school. Among the well-known residents who settled in the area were William G. Ackerman, William O. Giles, William Moller, William A. Varian, M.D., Benjamin T. Sealey, William H. Geer, John Parsons, M.D., and Rev. William T. Wilson. Oh yeah, and Joseph Henry Godwin.

Here’s a view of Macomb’s four-story grist-mill on the Spuyten Duyvil Creek, just east of the the King’s Bridge, in 1820. The mill eventually fell into disrepair and collapsed during a storm in 1856.

Joseph H. Godwin, the Squire of Kingsbridge

In 1848, Joseph H. Godwin purchased the Macomb mansion on the northwest corner of Broadway and West 230th Street and much of the surrounding property. He also enlarged the small island near the King’s Bridge in the Harlem River–called Lent’s Island in 1785 and Macomb’s Island in 1789–and built a summer home on it (naturally, he called this Godwin’s Island). A small footbridge connected the island to both Marble Hill and Kingsbridge.

From that day until his property was sold at auction in 1917, the land between Marble Hill, West 231st Street, and Bailey and Kingsbridge Avenues was known as the Godwin estate, and the old Macomb house was known as the Godwin mansion.

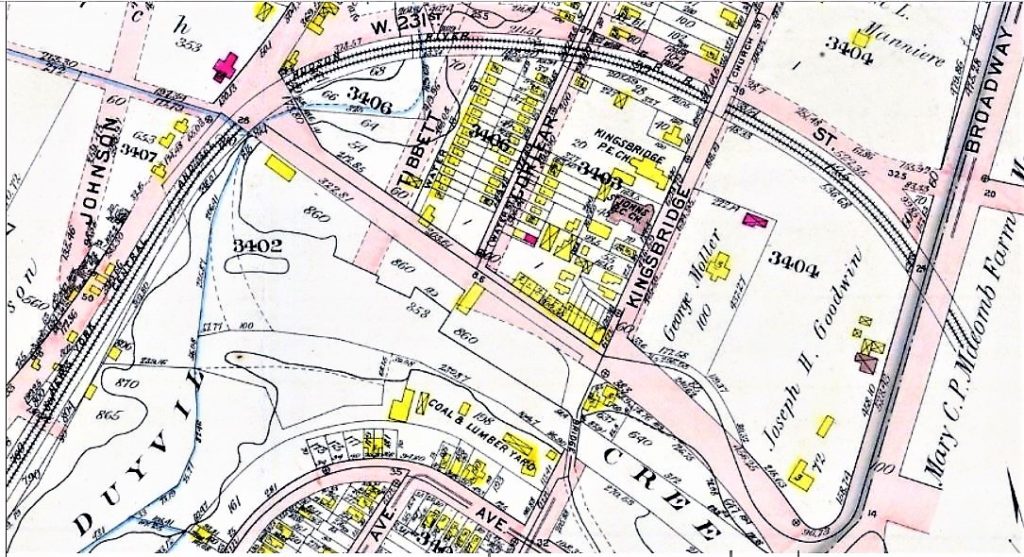

Godwin’s Island and the footbridge are depicted on this 1890 map. (Back then, Kingsbridge Avenue was called Church Street and Corlear Avenue was called Water Street.) This map also clearly labels the Godwin and Moller houses, and the 35th Police Precinct station house, which occupied one of small buildings on Godwin’s property (much of the land surrounding the police station was soggy marshland, and the station often flooded).

Born on Long Island in 1817, Joseph Godwin was a carriage maker, and later, a director of the Sixth Avenue and Ninth Avenue Elevated Railway Companies. He and his wife Phoebe had two children: Joseph H. Godwin Jr., born in 1846, and Emma L. Godwin, born in 1849. According to the 1875 tax assessments, the family owned 10 acres of land and three, one-and-one-half-story houses. The family lived in the old Macomb mansion at 332 Broadway.

The Godwin mansion around 1905, when water still flowed just south of West 230th Street, to the east of the bridge.

In his later years, Joseph listed his occupation as “Gentleman.” He also was known as “The Squire” for walking around Kingsbridge with a cane and wearing a top hat. He was quite neighborly, and often invited the village residents to pick cherries from his orchards.

On November 2, 1899, Joseph sold his island to John C. Rodgers for $2,500 as part of the Broadway Extension project for the new Broadway Bridge and IRT subway.

When the Harlem River was filled in around 1917, the island was buried under what are today the Marble Hill Houses.

On August 3, 1903, Joseph H. Godwin died in his historic home.

The old King’s Bridge in 1900, about 16 years before the Harlem River was filled in.

The Kings Bridge Hotel, pictured here in 1910, was on Broadway in Marble Hill.

A view of the King’s Bridge in 1885. By this time, the village had many houses, shops, churches, a grammar school, and a police station. The hill, which was part of Godwin’s estate, would later be developed as Godwin Terrace and Kimberly Place. The old Moller estate may be the home visible through the trees at the top of the hill.

The old Godwin mansion on the northwest corner of Broadway and West 230th Street in 1920, a few years after the river had been filled in, and shortly before the home was demolished to make way for a gas station. Notice the horse at left.

Memories of Old Kingsbridge

“The picturesque ‘hills of home’ are fast disappearing from our view, their once green slopes now scarred by a man-made growth of brick and concrete and steel. But once their rich beauty was unmarred.”–Margaret O’Rourke, Riverdale Press

In the late 1950s, the Riverdale Press published a series of articles about old-time Kingsbridge and the way it was in the late 1800s. Here are some memories from several former residents:

“I remember how the intersection (230th Street and Kingsbridge Avenue) appeared in 1892. On the northwest corner stood Scofuldor Market. It was one of about ten stores between Church Street (Kingsbridge Avenue) and Water Street (Corlear Avenue), which were destroyed by a fire on October 27, 1903. The Queen Anne building in the foreground on the west side was built by S. L. Berrian for Dr. Thomas Darlington. I started working on that building as an apprentice in March, 1892. Many years later, the building was moved to the east side of Godwin Terrace. The Moller house I still remember. I worked on a repair job there in October, 1896, with Thomas Commerford, another old-timer. The William Moller estate adjoined the estate of Joseph Godwin who, I believe, used to own the property between 230th Street north of the Hudson River Railroad and west from Broadway to Church Street.”

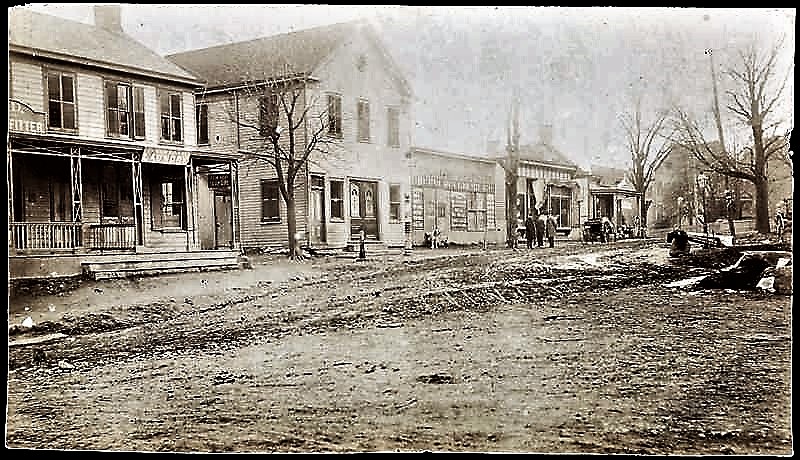

Here are some of the shops in the village of Kingsbridge in 1890, 13 years before the great fire.

“I remember it so well—the dirt roads, the modest homes on the tree-lined streets, the estates of the wealthy, the picket fences, Godwin’s Island, Tibbett’s Brook, the churches, the school and the row of stores that supplied our household needs. The stores stood side by side along the north side of the street, from the corner of Church Street [now Kingsbridge Avenue] to Tibbett’s Brook in the meadow below Riverdale Avenue. There was Scofield’s Butcher Shop with its sawdust floor and chopping block and sides of meat hanging on big meat hooks. From Kasper’s Bakery came the aromas of fresh-baked bread, cakes and pies. When my mother was low on homemade bread for breakfast, we were sent to buy Vienna rolls, which we considered a great treat. We enjoyed walking over the old Kings Bridge to Marble Hill, and smelling the salty meadows.”

“The business section was the western branch of this same main street [West 230th Street] and was then known as Riverdale Ave. A long line of wooden buildings stood along the north side of the street and a few others on the south side. Hecht, the druggist, was said to be as good as any doctor when it came to remedies for ordinary ills. His somber wife, Charlotte, had two black cats which walked undisturbed along the counter top whenever they desired. At Striker’s Dry Goods Store one could buy all kinds of yard goods for dress-making, and the twist, needles and pins, crinoline and ribbons, all necessary adjuncts. In Hall’s (later Gerrity’s), children’s pennies and two-cent pieces purchased their favorite sweets, and young men treated their best girls to heaping plates of ice cream. It was along this street, too, in Brucehauser’s Barber Shop that the first business telephone was installed. The butcher, the baker, the candle-stick maker were all there! The names of Dark, Polsenski, Berrian, Kasper, Powers, Schofield, Conklin, Burns. Stresman and Hannigan recall the merchants and tradesmen of a by-gone day. Pat Malone, the village blacksmith, had his shop nearer to River Street. Jimmy Ames’ stables and Sam BerrIan’s carpentry shop were at this site too. Across the road on the river side was Thome’s huge establishment with the coal yard and the hay and feed store. The docks at this river point made it an ideal situation for trading.”

“The village merchants could supply all the ordinary needs of the little community, but then, as now, mothers would make an occasional visit to the city to supplement the family stores. It was an all day excursion I am told, and when Grandmother dressed in her best bonnet and paisley shawl and set off on the “Dolly” with a market basket on her arm, her excited children waited hopefully all day for her return. What wonders she would have to tell about the big market and stores in the city, what surprises would be tucked among her packages, and what treats for them to taste! There were traveling merchants, too, with whom the villagers dealt. There was an Irish tinker who came to mend their pots and pans, and there were several pack-peddlers who sold sundry articles. Mommy the Peddler, one was called by the children because he would hail them with his familiar cry, “Go tell your mommy the peddler is here!” And another of these peddlers, an elderly Jewish merchant, caused the children to stand in awe as he neared because his magnificent features and long beard reminded them of St. Joseph. There were also wagon merchants who came from Harlem and Yonkers like Refter, the grocer, and Radcliff, the butcher.”

Most of the shops that these former residents spoke about burned down in the great fire of Kingsbridge on October 27, 1903.

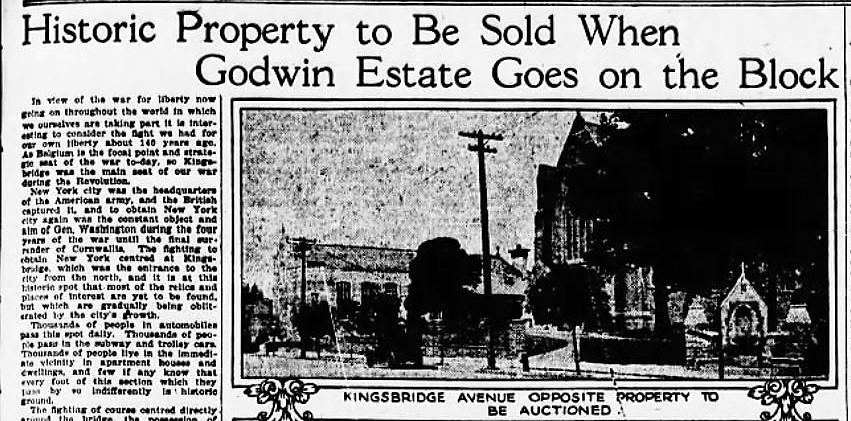

The Godwin Estate Auction, 1917

The Godwin Estate auction made the headlines of several New York newspapers in 1917.

During the early 1900s, while other sections of the Bronx were rapidly being developed, the area between 225th and 242nd Streets lay dormant, largely because of a general lack of public improvements there, but also because of the prevailing tendency of the local estate owners to hold on to their large holdings until the full effect of rapid transit improvements could be observed and measured.

When the Godwin property, comprising 231 lots, went on the auction block in 1917, it meant that practically all of the property between Marble Hill and the 231st Street subway station, Bailey and Kingsbridge Avenues, both on the east and west sides of Broadway, as well as the latter thoroughfare, could be distributed among a large number of investors and builders for development.

Here is a summary of the auction from the New York Herald, November 27, 1917:

One of the largest audiences in the history of the Vesey Street salesroom crowded into that place yesterday to attend the Godwin estate auction sale of 231 lots along Broadway, Kingsbridge Avenue, 230th and 231st Streets and adjacent thoroughfares. The parcels were sold at from $325 to $16,000 each. The entire Godwin holdings were assessed at $881,000. They were sold yesterday for a total of $415,000, an average of about $1,775 for 231 lots. Many buyers paid for their purchases with Liberty bonds and bank books. Lots were sold much below their valuations, which in a way indicates that the property is much over-assessed.

It wasn’t until almost 5 years after the estate auction that large apartment houses such as Godwin Court (erected in 1922) first appeared on Godwin Terrace. The buildings at 3054 Godwin Terrace (pictured here in 1940) were constructed in 1927; my father’s former building at 3033 Godwin Terrace was constructed in 1926 and purchased by I. & D.S. Meister, Inc. for $110,000 in 1934.

During the auction, the old Godwin home, which had been assessed for $22,000, was sold to Patrick J. Hangley of Jersey City, NJ, who bid $16,000. Patrick also purchased the lot adjoining on the north for $5,600. (Reginald Pelham Bolton had offered to buy the site for the New York Historical Society, but was out-bid by Patrick.)

In addition to the property, Patrick was presented with a cannonball and several arrowheads that had been found during excavation work on the property.

Cortlandt Godwin, president of the Campbell-Powell Shoe Company, purchased one lot near the old homestead for $4,000 and two nearby adjoining lots for $3,700. A large plot of land lying below grade in Albany Crescent was purchased by M. Passavanti, the owner of the abutting property on Bailey Avenue, where he operated a grocery store. He paid $2,100 for the land. Lots valued at $5,000 on the east side of Broadway between 231st Street and Kimberly Place, directly opposite the subway station, went for $1,425 to $2,500 each.

Here’s Kingsbridge Avenue at West 231st Street in 1923, just six years after the Godwin estate was sold at auction.

Other buyers of record included William F. Vidaly, John A. Maloney, Joseph J. Mc-Darby, Max Aronson. C. E. Grummerly, William H. Conway, Simon A. Polsky, D. F. Keyes, L. Lesner, Harry Store, William J. Fitzgerald, Elsie Boves, Parkhill Construction Company and Madeline Realty Company (William L. Thompson), Felix Muller, H. Grossman, Charles L. Grantin, John F. Gorman, Maurice Rosenberg, Salvador Carmona, and Hugh K. Smith.

Bailey Avenue, the eastern edge of Godwin’s property, was still undeveloped in 1920 when this photo was taken.

My dad’s old school, pictured here in 1930.

Following the auction, Joseph P. Day and J. Clarence Davies, agents and auctioneers, told the press:

“The sale was notable in several ways. First that such a large commitment of vacant land could be disposed of under existing war conditions, when everyone is conserving his resources to the utmost to support of government in the successful conduct of the war.

Second, it serves to show that people have not lost their confidence in the stability of New York City real estate as an investment. Third, we feel that we have kept faith with the buying public when we told them in our advertisements that there would be bargains and that the property would be sold without reserve or protection.

There is no question in our minds that when conditions again become normal—and the time is not far distant—those who bought at this sale will reap a reward commensurate with their optimism.”

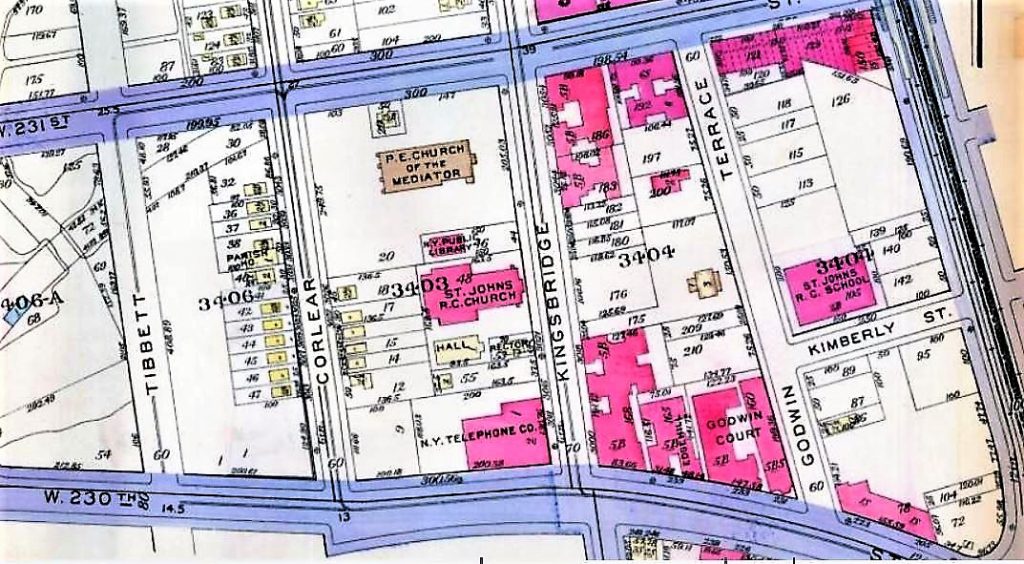

In June 1922, 11 lots at the northeast corner of Godwin Terrace and Kimberly Place were sold to the Roman Catholic Church of St. John as a site for a new school. The property had been purchased at the auction by Elsie Boves, Charles C. Grautin, and John T. Regan, and was valued at $35,000. The school officially opened on September 8, 1925, with 484 students. A third floor was added in 1946.

The Moller Estate on Godwin Terrace

I was always fascinated by the old frame building next to my dad’s former apartment building.

When I was a young girl, I was fascinated by the old frame house that seemed so out of place next to my grandmother’s apartment building. Even as a child, I recognized that the house was unique and historic, and I often wondered how it had survived so many years.

When I recently started researching this house, I began looking at old maps of the area. While looking at the 1904 map below, I noticed the large “George Moller” house to the west of what would later become Godwin Terrace.

I thought, this must be the house, but why is it farther west than where it stands today?

I had a strong feeling that the George Moller house (at right) was the old three-story frame house on Godwin Terrace, but I didn’t know why it appeared to be facing Kingsbridge Avenue on this 1904 map. (Also notice the large home and out buildings of the Godwin estate on Broadway, and the large coal and lumber yard on the landfill used to fill in the old Spuyten Duyvil Creek.)

Here’s what I found out about the Moller house.

The old frame house at 3029 Godwin Terrace had been the home of George H. Moller, his wife, Emma Godwin Moller, and their children, Harold, Maud, and Carl. According to an article in the Riverdale Press, back then, as the old maps confirm, the house had stood about 200 feet to the west on Kingsbridge Avenue, and was the center of the Moller’s estate (perhaps a wedding present to the bride from her father?) Ah-hah! My instincts were correct.

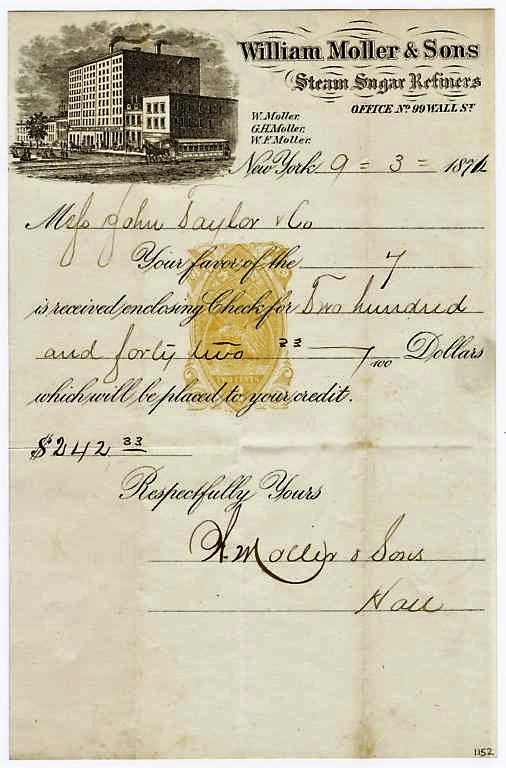

George H. Moller (1845-1901) was one of eight children born to William and Elizabeth Moller. William Moller (1817-1897) was a German-born merchant who was a central personality in the nineteenth-century sugar industry (he invented the Cut Loaf Sugar machine, a device which perfected production of the sugar cube). After the sugar refinery business failed in 1878, George became a broker and later vice president of the German Savings Bank of Brooklyn.

The Mollers were among the most popular sugar refiners during the Civil War era. By 1865, the firm was producing 17 million pounds of sugar a year, valued at $2.8 million.

George may have met Emma at a church function: Both George and Joseph Godwin were financiers and vestrymen of the Church of the Mediator on present-day West 231st Street (Godwin was a founder of the church, and he also served as a warden until his death in 1903).

According to census reports, George and his bride were still living with the Godwins at their residence in 1870, so they apparently moved into the Moller home sometime after this time.

George Moller died in the home in June 1901 at the age of 56. Emma purchased the home and property comprising eight lots for $16,000 at the 1917 auction of the Godwin property. She died in the home a year later on April 2, 1918.

In 1921, the last remaining 22 lots of the Godwin estate on West 230th Street, Kingsbridge Avenue, and Bailey Avenue were sold at auction. Sometime around 1925 or so, the Moller house was moved to Godwin Terrace.

In 1935, the parish of St. John’s purchased the old Moller mansion for $17,014, to be used as a convent for the sisters of the Religious of Jesus and Mary (these were the nuns who taught at my father’s school across the street). In 1950, when a new St. John’s Convent was erected on 230th Street and Corlear Avenue, the Moller house was remodeled to serve as the new home for the Brothers of Christian Schools.

By 1926, the date this map was created, the Moller mansion (small yellow structure) had somehow been moved to Godwin Terrace. Construction on my father’s apartment building had not yet started, although his school across the street at the northeast corner of Godwin Terrace and Kimberly Street was already open by this time.

Today, the former Moller estate is still part of the St. John’s parish, and still wedged between two brick tenement buildings.

It’s been almost 30 years since I’ve been to 3033 Godwin Terrace, but looking at the Google Streets and satellite photos, it doesn’t seem to have changed very much in all those years. Maybe Dad and I will take a ride there sometime soon to visit the old neighborhood…

In this aerial view, Godwin Terrace and the old Godwin property is at the lower left; the Harlem River and Spuyten Duyvil Creek were where the large housing development and playground are on the right. Godwin’s house and the King’s Bridge were in the middle, near the triangle on Broadway by the elevated train tracks.

Me, Dad, my stepmother, Terry, and my brother, Sean.

This is an incredibly fascinating heart-felt tale! Love anything about animals/old New York!

Really fascinating website.

I’m so happy that you enjoy it! It’s really a labor of love — I also love animals and Old New York, so it’s been a great way to combine two of my favorite things. Stay in touch by subscribing or follow me on Twitter — my first book is coming out in the fall from Rutgers University Press called The Cat Men of Gotham — all stories about men of Old New York who loved cats, with lots of obscure and fascinating history. Enjoy!

Thank you for providing insight into the neighborhood I called home during a service experience with the sisters of the Religious of Jesus and Mary. I taught at St. John’s School! I was sad to hear that their home on Godwin Terrace had been torn down. But loved rediscovering the area.