Captain John H. McCullagh’s dog took a few bites at Concordia Hall that disagreed with the hound — New York Herald, February 4, 1885.

In a recent post, I wrote about Mrs. Arthur Murray Dodge, an anti-feminist who cared deeply for children and stray cats, but who strongly opposed the women’s suffragist movement. This following animal tale of Old New York features a woman named Miss Block, a German feminist whom I’m certain was strongly in favor of giving women the right to vote.

Take special note of the anti-politically correct language used by the reporter for the New York Herald, and also note the attitude of the police captain and sergeant. Then just imagine if Twitter and other social medial platforms had been available a century ago!

“Last evening, about seven o’clock, some thirty fat, chubby looking German ladies assembled in the second story front of No. 414 East Fourth Street. Singly timid and harmless, collectively they constitute the formidable and combustible body which goes by the name of the Women’s Socialistic League—Sozialistischer Frauenbund.”—New York Herald, February 4, 1885

According to the article, the women had met two nights before at the Concordia Hall, a popular place for political rallies and motivational speeches located on Avenue A between East Second and East Third Streets. During this meeting, Captain John H. McCullagh of the Seventeenth Police Precinct knocked Ms. Block down to the ground and kicked her “brutally.”

Then, according to Miss Block, the police captain set his bloodhounds on her. She heard him call to his black hound, Black Jack, and say, “Now, chew her up, Jack. She’s tough and old, I know, but it all comes in the line of duty, old boy.” The dog reportedly bit her and tore her clothing in several places.

After hearing Miss Block’s harrowing tale, a reporter from the New York Herald headed over to the police station at 79-81 First Avenue (southwest corner of First Avenue and East Fifth Street). The reporter related “the blood curdling charge” to Sergeant Joseph Hagerty, who in turn replied:

“Black Jack did eat something at the meeting in the Concordia Assembly Rooms which seriously disagreed with him. The boys thought it was a dynamite petard that he had swallowed, but perhaps it was only Miss Block.”

And that, as they say, was the end of that. Black Jack was simply pardoned and poor Miss Block had no more recourse in the matter.

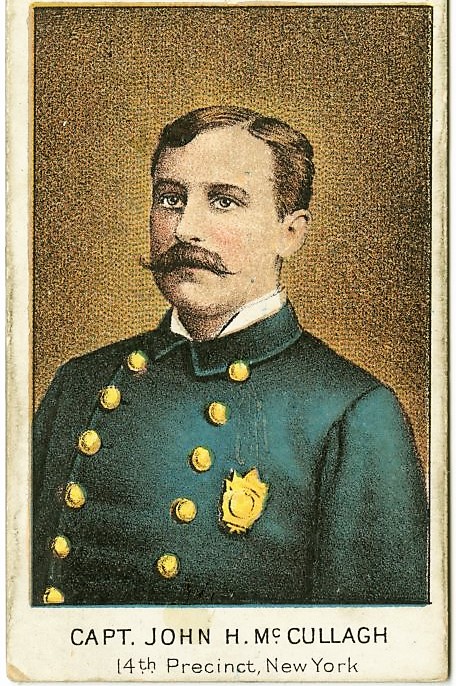

Captain John H. McCullagh

When this story took place, John H. McCullagh was the captain of the Seventeenth Precinct, which was bounded by Houston Street, Avenue B, Fourteenth Street, Fourth Avenue, and the Bowery. The station house on First Avenue dated back to 1853, which is when the precinct’s headquarters were moved from Third Street and the Bowery.

Police Captain John H. McCullagh was described as “a pretty man,…strong and well featured, with a sharp but kindly eye, a firm nose and chin, a capital forehead, and a resolute but sympathetic mouth, shaded by an ample dark mustache of cavalry trim.”

John McCullagh was born in the County Tyrone, Ireland, in 1842. He and his family came to America in 1853, and they resided at Irvington-on-the-Hudson, where John was very active in all sorts of athletic sports and games. When he was 21, McCullagh met some members of the police force during the Draft Riots, and he decided that police work was his calling.

McCullagh was first assigned to the Leonard Street station on February 29, 1864. But it was during his time with the Twentieth Precinct (Thirty-seventh Street squad) on the west side of Manhattan that he made a name for himself.

Back then, there was a group of ruffians called the Hell’s Kitchen Gang who committed numerous robberies at the Hudson River Railroad Depot and terrorized the neighborhood. One night, two hogsheads of hams were stolen from the train station. Hearing of the robbery, McCullagh went down towards the depot. On the way, he encountered a notorious thief named “Dutch Heinrich” and two of his companions. A great struggle ensued, but after a time the thief went under.

Unlike Black Jake (or Captain McCullagh!), Heinrich was tried, convicted, and sent to state prison for five years. McCullagh was promoted to the rank of roundsman for the Tremont Precinct on East 126th Street, where he was recognized as a “magnificent equestrian” on the mounted police squad. He also served as a roundsman and a sergeant for the Grand Central Station and Thirty-fourth Precinct before being promoted to captain on April 20, 1872.

The Hudson River Railroad Depot on Thirtieth Street and Tenth Avenue was the site of numerous gang-related robberies in the l800s. Abraham Lincoln passed through this station two times, so to speak: the first time when he was heading to his inauguration and the second time when his body was transported to his burial site in Albany. The station was demolished in 1931 to make way for the Morgan Post Office.

Although McCullagh got away with releasing his hound dog on an innocent civilian, he did have to lick a few of his own wounds, so to speak, during his years in the police department.

One time he reported a reckless policeman named James G. Taylor, who was later dismissed from the force. Taylor got his revenge by shooting McCullagh on the corner of Thirty-seventh Street and Ninth Avenue. McCullagh was severally wounded in the attack. Taylor was sent to Sing Sing prison for five years.

McCullagh was also shot in the leg during the Orange Riots of 1871. He returned to the job after only one month of recuperation. Over the next 12 years, he was put in command of several police stations, including those on Leonard, Prince, Oak, Fifth, and East Thirty-fifth Streets.

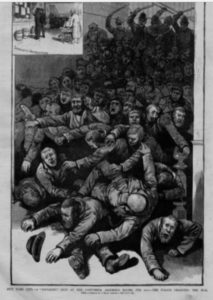

In February 1885, a riot broke out at Concordia Hall between anarchists and socialists over the legitimacy of the use of dynamite by Irish Nationalists in London. Although off duty, McCullagh tried to call for order, but was hit from behind with a chair. It was reported the police were attacked with guns, knives and clubs.

John H. McCullagh died in his room at the East Thirty-fifth Street police station on March 6, 1893. He had been suffering from inflammatory rheumatism, and on the morning of his death, his throat had closed up, necessitating an emergency tracheotomy performed by Police Surgeon Fleuer and two other doctors.

Because of the medical emergency, the doctors could not transport him to his home at 148 East Forty-ninth Street. His oldest son, John, then a sophomore at Yale, arrived after his passing.

His body was taken by train to Irvington, where he and his wife had a country home.

Concordia Hall on Avenue A

Concordia Hall, at 28-30 Avenue A, was a German club house and ballroom at the heart of New York City’s Little Germany, called Kleindeutschland. Many German societies, including the Melomanen (music lover) Society, the Theodor Koerner Lidertafel (a men’s vocal group), the German-American Teachers Association, and the Marshner Maennerchor (men’s chorus) were headquartered in the circa 1871 building.

In the 1880s, Concordia Hall also became a meeting place for local political and social groups, such as the 10th Assembly District Republican Association and the Sozialistischer Frauenbund.

In 1899, the city proposed to convert the hall into a court house. In the proposal, the five-story building was described as follows:

“The large room is fairly lighted, at the easterly end, by windows opening on the yards of the adjacent lots, and at each easterly corner by windows opening on light shafts; on the Avenue A end the light is ample. There are two ventilators in the ceiling.

So long as the adjacent lots remain as they now are, the light and ventilation will be sufficient, but, this being an interior lot, the possibility of adjacent owners building up to rear lines of their property ought to be considered. This being a tenement district, it is not probable that such buildings will be erected, but the possibility should be provided for, if a long lease is entered into.”

The old Concordia Hall building (five stories with tower and cupola) on Avenue A in the early 1940s. By this time, the building was occupied by the Burger-Klein furniture store.

The proposal was voted down, and the building continued to serve as an assembly hall for another 20 years (from 1910 on it was alternately called the Progress Assembly Rooms, Progress Assembly Hall, and Progress Casino).

Sometime around 1920, the building was converted into a department store. By 1939, the building was the home of the Burger-Klein furniture store.

In 1959, a four-alarm fire destroyed the roof and top floor of the building–including the central tower and cupola–resulting in a significant alteration of building’s façade. In other words, a handsome building was converted into a very ugly one.

Although a Burger-Klein sign adorned the side of the building for many years after the furniture store closed, during the late 1990s until about 2013 the building was home to Gracefully, an upscale deli.

By 2014, construction of a New York Sports Club had begun on the site where, 130 years earlier, a German feminist named Miss Block was attacked by a police dog named Black Jack.

The old Concordia Hall building on Avenue A looked like something from a bad retro movie in 2013.

Here’s the old Concordia Hall in 2014, making way for the New York Sports Club.

Here’s what the old Concordia Hall looks like today, in 2018.