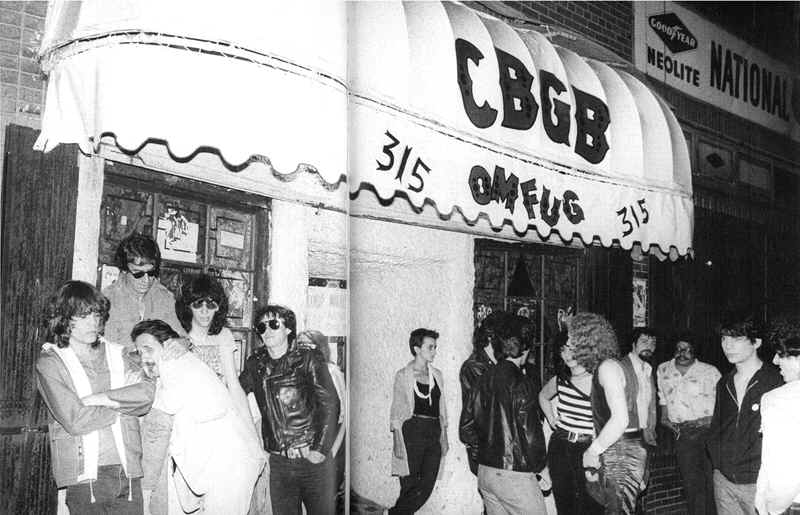

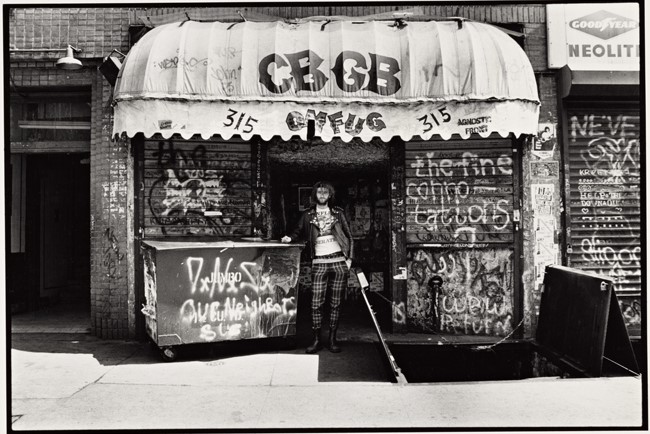

From 1973 to 2006, CBGB (aka CBGBs) occupied 315 Bowery on the Lower East Side. The place was small and grungy, but some of the greatest bands of the 70s and 80s made their U.S. debut here.

“This ain’t no party, this ain’t no disco

This ain’t no fooling around

This ain’t no Mudd Club, or CBGB

I ain’t got time for that now”–Life During Wartime, Talking Heads

In its heyday during the 1970s, the famous grungy dive bar at 315 Bowery called CBGB was like a second home to bikers, junkies, prostitutes, and inebriates (the bar was next to the Palace Hotel, which was reportedly the largest flophouse for homeless men in Manhattan). It was also the birthplace of some of the greatest punk and alternative rock bands in New York City.

At CBGBs, bands and singers such as the Talking Heads, Ramones, Police, and Patti Smith made their U.S. debuts, sometimes before a small audience of about 10 people (mostly the band member’s girlfriends or boyfriends). I still enjoy listening to the music of many of these bands today, but I also love the fact that 100 years before CBGB opened its doors, many beautiful song birds displayed their singing talents at 315 Bowery, when it was the second home for William Frederick Messenger, a founding member of the New York Canary Bird Fanciers Association.

The New York Canary Bird Fanciers Association

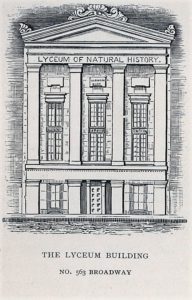

In 1847, a small group of bird fanciers got together to exhibit their collections of “rare fancy and singing birds” at the Lyceum Building at 561-565 Broadway. It was reportedly the first bird show of its kind to ever take place in the United States.

In addition to displaying the collection of birds loaned for the occasion by numerous private individuals, the exhibit featured beautiful flowers and evergreens. According to news reports, tickets were 25 cents for a gentleman and lady.

The event must have been quite successful, because the bird fanciers went on to hold annual exhibits through at least 1862, which is the year the bird fanciers (later called the Empire Canary Bird Fanciers) displayed their birds at the shop of William Messenger, a prominent importer and dealer in rare and fancy birds.

The New York Academy of Sciences began as the Lyceum of Natural History on January 29, 1817. The Society moved into the building at 561-565 Broadway in May 1836. The 50- by 100-foot building featured a library of natural history as well as a spacious hall, lecture room, and meeting rooms. The New York Canary Bird Fanciers Association held their first exhibit in this building in 1847.

Sometime around 1848 the men began holding regular meetings at Lafayette Hall, a “sporting place” at 597 Broadway that was popular for Keno gambling. The fanciers held several exhibits (which they called “grand annual fairs”) at this hall, including their fourth annual fair in December 1851, which was described in the newspapers as follows:

“It is believed that this Exhibition will be more perfect in its arrangement than any before given. The number of birds exhibited will be much larger, while in richness of color and symmetry of shape they will surpass any heretofore shown. It has been admitted by European Fanciers that our birds are unequaled by any in the world. Those who are ignorant of the change that has been made in the shape and size of the ‘little Canary’ by careful cultivation will be both astonished and delighted by a visit to their novel Bird Fair.”

In 1855, the bird fair took place on the ground floor of the frame building at 323 Bowery, where William Messenger had his shop. By 1862, Messenger had moved his bird store to 315 Bowery, then a two-story frame shop and house.

That year, the club members called themselves the Empire Canary Bird Fanciers, and this was the third annual show under their new name. The society had only 12 members, eight who resided in Manhattan and four in Brooklyn.

According to the New York Tribune, the show featured an Antwerp painting of a “long-breed” canary bird, which was used as “the standard of beauty” for judging the birds. The pair of birds (there were 29 pairs in the competion) that most closely matched the painting would win the highest prize, which was a diploma setting forth their points of high breeding.

The birds were judged by form and color: “Of course the value is graduated by the perfection of form and color; the deep, rich yellow is more prized than the mealy, mottled birds of imperfect hue, ranking lowest of all; but a perfect pair of cinnamon color, would command almost any price which the owner might demand.”

According to the article, the importers of long birds purchased them in Brussels, Antwerp, and Dietz, “where they obtain prices almost fabulous. Fifty dollars for a breeding pair is not as unusual price, and for birds bred in this country from such stock, $25 a pair is frequently paid.” (Thus, winning the diploma could pay off nicely for a breeder.)

In 1849, William Messenger’s fancy bird shop was located on the east side of Broadway, between Houston and Prince Streets.

The committee chosen to vote on the birds included William Messenger, John Higginbotham, Brooklyn; John Murray, Brooklyn; William Manson, Brooklyn; and Joseph Silvey, Manhattan.

In later years, prizes for the best male and female canaries were silver spoons for first, second, and third place; and gold pencils for fourth, fifth, and sixth place. William Manson and John Higginbotham both did quite well in 1862 — I imagine they must have won a lot of spoons and pencils with their prized birds.

William Frederick Messenger, Bird Fancier

William Messenger (aka Messinger) was born in Germany on February 13, 1815. He and his wife, Mary M. Lantz Messenger, also born in Germany, had nine children: William, Frederick, Henry, Mary, Emma, Edward, Charles, John, David.

William was a dealer in long-breed canaries, mocking birds, blackbirds, thrushes, and singing German birds, which he sold at his shop–W.F. Messenger’s Empire Bird and Cage Store–at numerous locations throughout the city. During the 1850s and 1860s, he had a shop at 73 Bleecker Street, 564 1/2 Broadway, 609 Sixth Avenue, and finally, by 1859, at 315 Bowery.

William died on March 14, 1874, and was buried in the family plot at Oak Hill Cemetery in Nyack, New York (Rockland County).

A Brief History of 315 Bowery

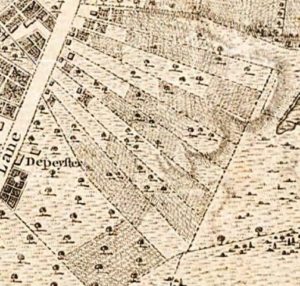

The land that now comprises the Lower East Side was originally part of the Dutch West India Company’s Bowery No. 2, acquired by Petrus Stuyvesant, and Bowery No. 3, granted to Gerrit Hendricksen and later acquired by Phillip Minthorne around 1732. Both these large farms were bordered on the west by the Bowery Lane (today’s Bowery).

The fanlike arrangement of the nine Minthorne family farms along Bowery Lane is clearly visible in this 1776 Ratzer map. Margaret Minthorne and her husband Nicolas Romaine inherited the southern-most lot, where are story at 315 Bowery takes place.

Following Phillip Minthorne’s death in 1756, much of the eastern half of the 110-acre bowery was sold to John Jacob Astor. The western half was divided into 27 individual lots, three for each of his nine children: Philip Minthorne, a farmer; John, a cooper; Henry, a tinman; Mangle, a cooper; Hannah, the wife of Viert Banta, a house carpenter; Hilah, the wife of Abraham Cock, a cooper; Sarah, the wife of Samuel Hallet, a carpenter; Frankie, the wife of Paulus Banta, also a carpenter, and Margaret, the wife of Nicholas Romaine, a house carpenter.

Lot #72, aka 315 Bowery, is located on what was Margaret and Nicholas Romaine’s southern-most tract, as shown in the map at right.

In 1805, the junior Nicholas Romaine (a blacksmith) and his wife Elizabeth sold their property to the Trustees of the Bowery Village Methodist Episcopal Church. The land in turn was conveyed to Joseph Graham, “a good man, full of faith and of the Holy Ghost,” who served as a class leader of the church from 1796 to 1812.

Joseph Graham was born sometime around 1764. Old census reports dating back to 1790 show that he resided in what we now consider the Lower East Side, but unfortunately they do not provide detailed information such as place of birth, names of family members, or street addresses.

Based on advertised public auctions and other reports in old newspapers, I do know that Joseph owned several parcels of land on the Bowery Lane, and that he was a gardener and a volunteer fireman with Engine Company No. 10, but I can’t confirm if he ever resided at 315 Bowery or just owned the land.

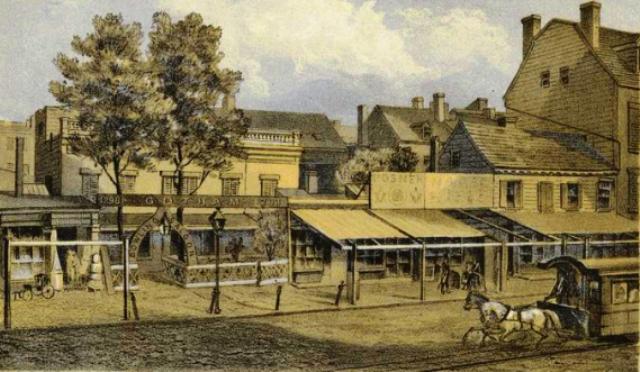

This illustration of The Cottage, aka, The Gotham, at 298 Bowery, gives you an idea of what the Bowery looked like in the 1800s.

According to an 1820 city directory, 315 Bowery was occupied by Jane Henderson. Nearby neighbors included Catherine Romaine at 309 Bowery; Philip Romaine, a butcher, at 307 Bowery; and John Flandreau, a carpenter, at 313 Bowery. In 1839, John Delahay, a plasterer, had his shop at 315 Bowery (according to an 1840 fire report, 315 Bowery was a two-story frame building). His neighbors included Antoine Boutete, who sold cigars at 313 Bowery; Ernest Keyser, who lived at 311; Catherine Romaine, who was still at 309; James H. Mackenzie, a hatter, at 307; and Allen Woddle, a painter, at 317 Bowery.

Sometime before his death in 1844, Joseph conveyed his land on the Bowery to William L. Lippincott. Jacob C. Weeks, a coal dealer, obtained the “houses at 313 and 315 Bowery” in 1847. In 1848, when he was selling coal from his shop at 313 Bowery, Jacob advertised apartments to let in the upper floors of both buildings. The Weeks Estate held onto the two buildings–which were converted into six-story tenements (10 apartments each with stores on the ground floor) in 1878–until 1934, when the property was purchased by an unknown investor.

In December 1929, four people were injured and a dozen families lost their homes when a two-alarm fire started in the Atlantic Paper and Restaurant Supply Company on the ground floor of the six-story business and tenement at 315 Bowery.

Fast forward to 1973, the year Hilly Kristal (1931-2007), a musician and former marine, opened CBGB at 315 Bowery, with the intention of booking Country/BlueGrass/Blues bands and Other Music For Uplifting Gormandizers. Much has been written about the club, so I’ll stick to the old history here, and just note that CBGB closed on October 15, 2006.

A bank threatened to raze the place and move in, but in 2008 John Varvatos saved the building by opening his men’s clothing store on the ground floor.

Here’s CBGB in 1986. Today the ground floor is occupied by John Varvatos, a men’s clothing store. Although the store does not have any singing birds, it reportedly has a staff that is made up of either musicians or “music-obsessed.”

An Aside: The Bowery Village Methodist Episcopal Church

Bowery Village “was a rugged belt of land, with here and there a garden and a solitary house, to diversify the barrenness of the stunted pasture lots with their dilapidated fences. Bowery Village consisted chiefly of a long unpaved street of straggling houses, running northward from the two-mile-stone; dreaming little, as yet, of the Russ pavement and the car track.” – Bowery Village M.E. Church: A Discourse, by Rev. F. Bottome, 1864.

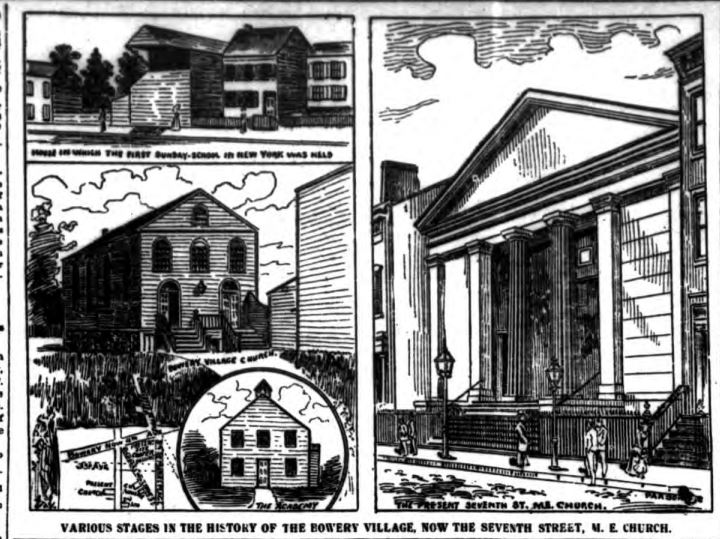

The Bowery Village Church began as the Two-Mile-Stone Church in 1784, and eventually became the Seventh Street Methodist Church in 1894.

Joseph Graham was first appointed class leader of the M.E. Church in 1796, when it was called the Two-Mile-Stone Church (the two-mile stone, which marked two miles from Federal Hall, was directly opposite today’s Cooper Union). The church was founded in 1784 by John and Gilbert Coutant, who held early meetings in the upper room of their house, which stood on the lots now occupied by the Cooper Union. During the week, the upper room was a shoe shop and store; on Saturday night, it was cleared out and swept to prepare for Sunday-morning prayers.

In 1795, a small, two-story frame house with gable front was erected on a knoll in the Bowery Village, on the west side of the Bowery Lane near today’s Eighth Street (the church was actually located on a foot path called Nicholas William Street, named after Nicholas William Stuyvesant). The new building, often called The Academy, was used as both a school (it was the first Sunday school in the city) and a church. The bucolic setting featured a large shade tree, grazing cows, and a pond filled with ducks.

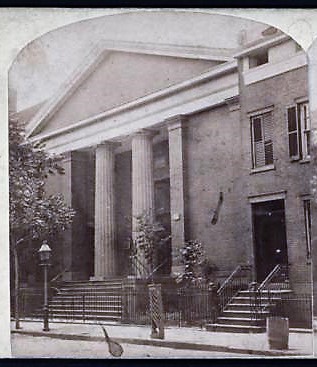

The new Seventh Street Methodist Episcopal Church was built on East Seventh Street near Hall Place (now Taras Shevchenko Place) in 1894.

In 1818, a larger house of worship was built alongside The Academy using some of the timber from the John Street Methodist Church, which had been demolished a year before. The frame building was later moved “across the lot” to Seventh Street, where it was replaced in 1835 by a brick church.

The new Seventh Street M.E. Church was built in 1894 on the south side of East Seventh Street, between Second and Third Avenues. The parish of the St. George Ukrainian Catholic Church purchased the church in 1911 and completely rebuilt it from 1976 to 1978.