This photo has nothing to do with Bellevue Hospital, but I just love all of Harry Frees’ animal photos from the early 1900s.

Miss Lillie James had a lot of cats. She adored her pets, but her extreme affection for them eventually took over her life. Soon she could do nothing but worry that her feline companions would abandon her or die. Her sister, Miss Leia James, told the doctors at Bellevue Hospital that Lillie had been driven crazy by her cats.

Miss Lillie James was literally, in fact, the proverbial crazy cat lady.

It sounds funny at first, but unfortunately this story has a tragic ending. Because Miss Lillie really did have a health issue that caused her to become mentally unstable.

And in the late 1800s, all the doctors could do was admit her–but not her cats (as she had insisted)–to the Insane Pavilion at Bellevue Hospital.

The Insane Pavilion at Bellevue Hospital, which was located on the 26th Street side of the large hospital complex, opened on June 21, 1879. This image was photographed inside the main hall looking toward the front door. University of Rochester Collections

Miss Lillie was only 32 years old when she began to worry obsessively about the 11 cats living with her at 50 East 133rd Street, in the Port Morris section of the Bronx. When it finally got out of hand, her sister brought her to Bellevue Hospital. Miss Lillie decided to bring two of the cats with her to have them committed, also.

When the doctor declined to admit the cats, Miss Lillie became greatly agitated. She told him that the cats were undoubtedly insane, while she was perfectly fine and clear of mind.

Right on the spot she denounced her affection for the two felines, stating, “It is their conduct that has placed me in my present condition. These cats and nine others have conspired against me and affected my health, with the idea of getting possession of my property. Are these guilty cats to go free while I am locked up?”

Miss Lillie then shook her fist at the two cats and was led away. Her sister told the doctors she would care for the cats until they could be “dealt with by the law.” (In other words, I think this story ended badly for the cats, too.)

The New York Times, February 18, 1899

The Great Cat Hunt at Bellevue

Fast-forward four years to 1899, when there were more than three dozen cats living at the large Bellevue Hospital complex. I don’t think any of these cats were the two pets that had belonged to Miss Lillie (some of the cats were reportedly 12 or 13 years old), but it makes for a great story to suggest that this scenario could be possible.

According to The New York Times, on February 17 of that year, 30 hospital attendants were ordered to round up all the cats and “put a stop to the annoyances to which they have been subjecting people thereabouts.” After a two-hour chase, the men were able to catch only 18 cats, many of which were lame and did not have a fighting chance to escape.

One cat, named Dewey, had only three legs, so he was easy to catch. Stockings, one of the cats who made his home in the “alcoholic’s ward,” ran up a tree in the yard but was later captured. Another poor cat with a broken back was also easily apprehended.

Perhaps it was a good thing that there were so many cats at Bellevue Hospital. In early years, the hospital was overrun with hundreds of rats (as this illustration of the women’s ward was intended to depict). In fact, in 1860 a newborn infant was reportedly gnawed to death by rats. The cats probably performed a great service by keeping the rat population down.

Jerry, the cat attached to Superintendent William B. O’Rourke’s office, thought he was safe and did not try to run. Big mistake.

Jerry, Dewey, Stockings, and the other captured kitties were turned over to the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, and carted off by wagon to the gas chambers. (When it came to cats and dogs, the S.P.C.A. was more like the Society Pretty Cruel to Animals in its early days.)

The Bellevue Hospital Stables Cat Goes Mad

I don’t know what happened to all the cats that escaped from the hospital attendants that day, but I do know that at least one cat continued on at Bellevue Hospital, albeit, he was relegated to the hospital stables. This was a large nameless black cat who was apparently the general pet of the stable workers.

One day in October 1906, three hospital workers got into a fierce battle with this cat. Ambulance drivers Thomas Couglton and John Russell and watchman John Hayden were all scratched and clawed at during the attack.

According to an article in the Buffalo Commercial, Thomas had been summoned to the stables for a routine ambulance call. As he started to prepare the ambulance, the cat jumped onto his shoulders, clawed at him, and sank his teeth into Thomas’ neck. As Thomas roared in pain, Hayden and Russell came to his rescue.

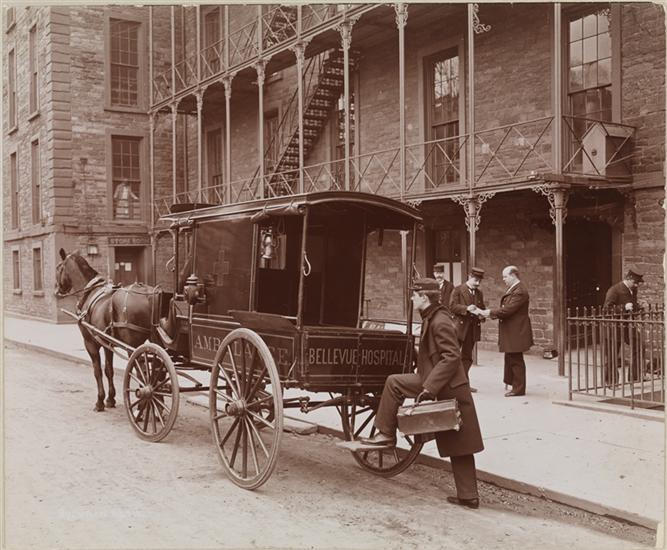

The country’s first ambulance service started at Bellevue in 1869. The fleet of horse-drawn ambulances used gongs to get through busy streets and carried a container of brandy to help relieve of pain. This picture was taken in 1896. Museum of the City of New York Collections

It took the three men several attempts to pry the cat away from Thomas. Sadly, the men had to kill the cat in order to subdue it.

Thomas completed his ambulance call, but when he returned to the stables the ambulance physician noticed that his coat was covered in blood. Thomas’ neck and hands were badly wounded and swollen. Dr. Lyndsey treated Thomas in the ambulance. An examination was also ordered to determine whether or not the cat had rabies.

A Brief History of Bellevue Hospital

In the colonial days of New Amsterdam, the poor fell under the care and expense of the church. A fund for their support was collected by voluntary contributions to the poor-boxes and distributed by the officers of the church. The needy were assisted in their own houses, so there was no need for the city to provide a shelter or other services.

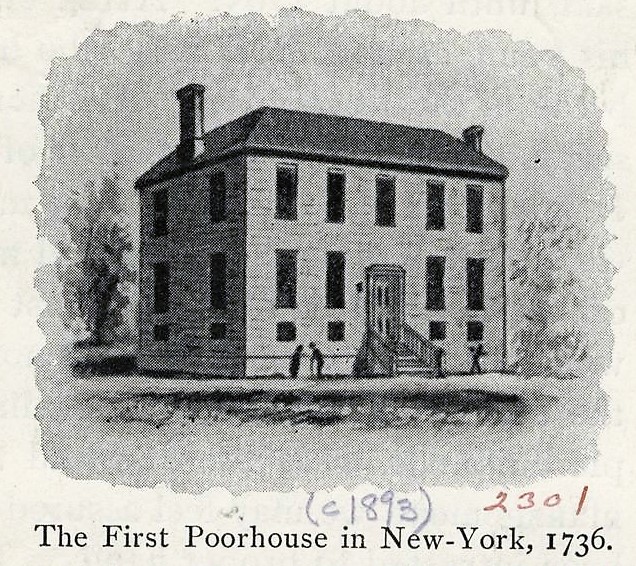

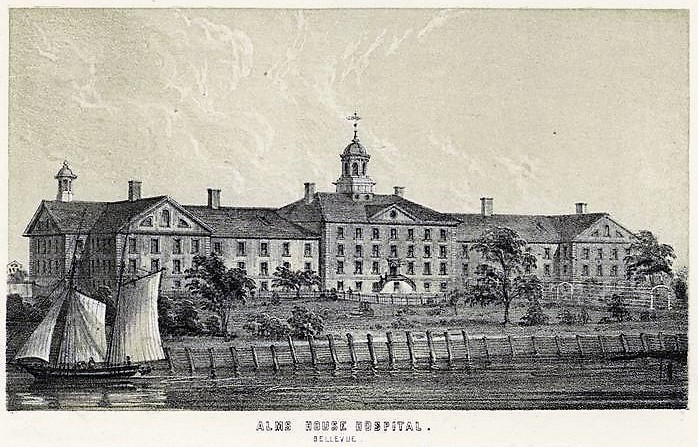

The original Almshouse on the site of present-day Chambers Street in 1736. The top floor had a small hospital with six beds.

Eventually, when the population had reached about 1,000, the city opened a shelter for the poor on the west side of Broad Street, just north of Beaver Street. In December 1658, Master Jacob Hendrickszen Varrevanger, surgeon to the Dutch West India Company, suggested that a hospital also be erected on this site. This was reportedly the first hospital ever constructed on American soil.

By 1731, the city had 8,628 residents, many of whom were poor or sick (a smallpox epidemic that year killed many people). Three years later, on November 15, 1734, under Mayor Robert Lurting, the Common Council appointed a committee to look into purchasing a house suitable to be used as a workhouse or almshouse. The committee recommended building on unimproved lands belonging to the city, situated on the north side of the lands of the late Colonel Dongan, commonly called the “Vineyard.” Today we call this area City Hall.

Lindley Murray, one of 12 children born to Robert and Mary Murray, purchased the property and estate called Belle View in 1783.

The two-story, 56- by 24-foot building with cellar (shown in the illustration above) was ready for occupancy in 1736. It was the called the Publick Workhouse and House of Correction of the City of New York, and it featured workrooms and storerooms in the cellar, a dining room on the first floor, living quarters for the keeper (John Sebring) and his family on the second floor, and an infirmary with six beds for Dr. John Van Beuren, also on the top floor.

Fast-forward again to 1794, the year the worst yellow-fever epidemic in New York began. In need of a large facility to isolate the victims of this disease, the city purchased the lease on a large mansion on the East River belonging to Henry Brockholst Livingston (who in turn had been leasing the property from Nicholas Devise).

Henry Brockholst Livingston, a Revolutionary War officer and Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, called his estate “Belle Vue.”

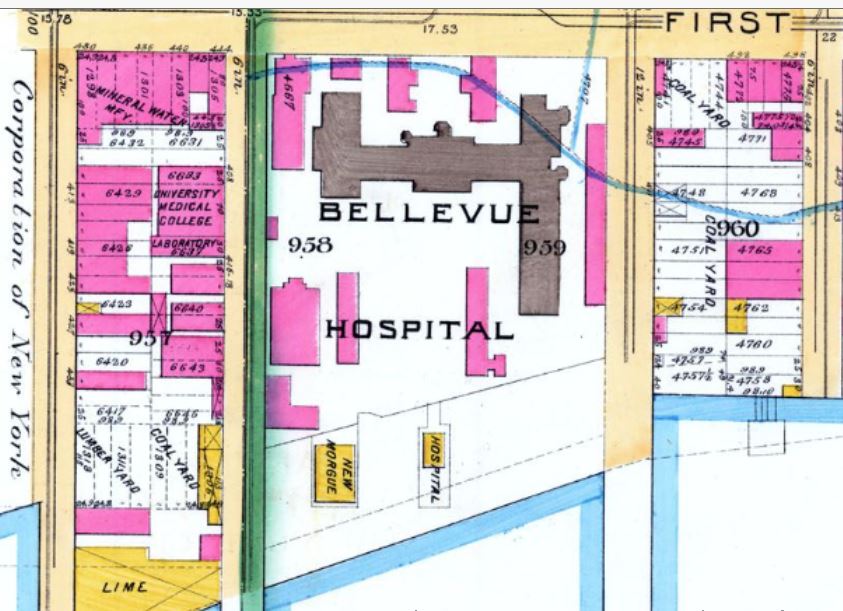

The property, once part of the old Kip’s Bay Farm (Jacobus Kip), was about five acres in total, bounded by the river and First Avenue between 25th and 28th Streets. The land had been passed on from Kip to Peter Keteltas in 1765; then to Martin Hoffman some time later; and then to Robert Leake in 1772. Leake named the property and mansion Belle View.

In 1783 the property was purchased by Lindley Murray, a son of Robert and Mary Lindley Murray (of New York City’s Murray Hill neighborhood). While residing in England in 1793, Lindley conveyed this property through his attorney to Brockholst Livingston, who retained the name but with a different spelling: Belle Vue.

Belle Vue served as the city’s quarantine center until 1811, when the city decided to open a larger, more proper hospital on the East River site. Four years later, what was then called the Bellevue Establishment opened on an expanded site that totaled 28 acres and included land from the old Rose Hill Farm.

Enclosed within a 10-foot-high stone wall were numerous buildings, including a school, morgue, bake house, three-story penitentiary, greenhouse, almshouse, icehouse, carpentry shop, pest house (the quarantine), and, of course, the hospital proper.

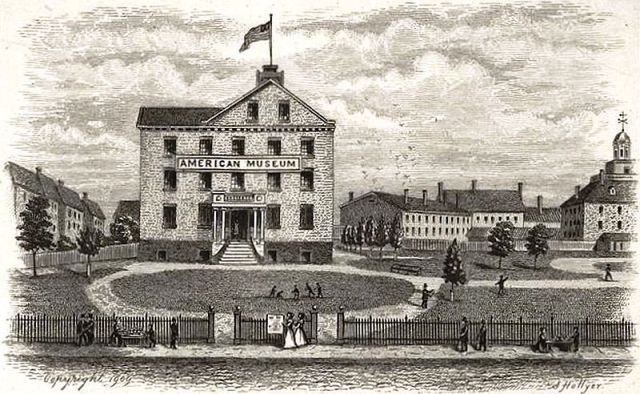

After the city moved the “hospital” to its new location on the East River in 1811, the almshouse building was expanded and occupied by several institutions, including the city’s first non-profit cultural center called the New York Institute (shown here), the Lyceum for the Deaf and Dumb, and the American Museum, which John Scudder opened in 1816. The building was destroyed by fire in 1855; today this site is occupied by the Tweed Courthouse at 52 Chambers Street,

This illustration of Bellevue Hospital was created in 1852. New York Public Library Digital Collections

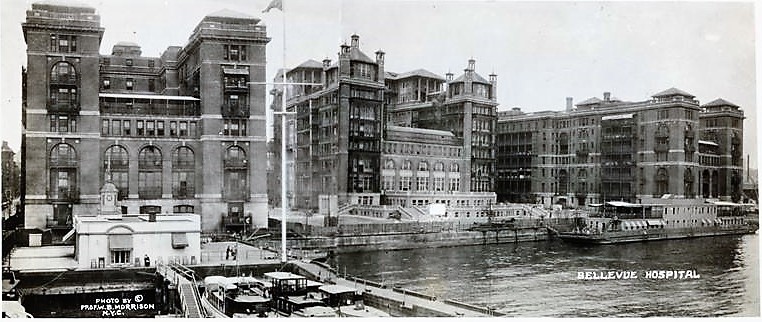

The Bellevue Hospital complex, 1895. During this time, the hospital–closest to river–was one of the smallest buildings in the complex. Note the blue lines at top, which denote the old water line of the East River before the days of landfill and the FDR Drive.

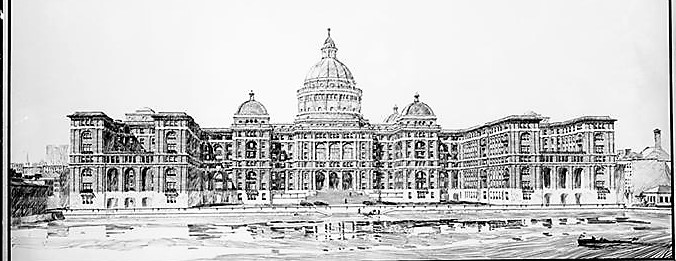

In 1905, New York City architects McKim, Mead, and White developed a master plan to create five interlocking pavilions (featuring a large, central domed structure) to replace the old buildings of the Bellevue complex. The master plan was reduced to three, nine-story pavilions, which were constructed between 1908 and 1939.

Here’s a photograph of Bellevue Hospital many years before thousands of tons of landfill were used to create the East River Driver (later, the FDR), which is why all the buildings are so close to the water’s edge. NYPL Digital Collections

By the mid-1950s, Bellevue Hospital was a complex of about 15 buildings with 2,670 beds and an average daily population of about close to 10,000. Its grounds included a post office, a state court (for commitment hearings of psychiatric patients), two public schools, a prison, several libraries, three chapels, and a mortuary.

A master plan drafted in 1957 called for the replacement of almost every existing brick building, and in 1973 a gleaming 25-story, $160 million tower was completed on the eastern part of the grounds near the FDR Drive. The building features rooms for one, two, or four patients with sweeping view of the East River below. Two of the original McKim, Mead, and White pavilions still stand, but they look minuscule next to the tower.

There are no cats at the hospital anymore, but the Bellevue Hospital Garden features several stone sculptures of various animals, including a dog, eagle, and pig.

An aerial view of the Bellevue Hospital complex in 2018, courtesy of Google Earth.