The first Subway Nellie was an Irish setter who arrived at the construction site of the new subway station at Bleecker and Elm Streets in 1903. (This is not Nellie.)

A few years ago, I wrote about a mixed-breed dog who made herself at home at the excavation site of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) Joralemon-Street Tunnel under the East River. The men christened the dog Subway Nellie, in order to make sure no one confused her with all the other dogs named Nellie in the neighborhood.

What the workers may not have known when they gave Nellie her name in 1905 was that another dog with the very same name had joined the subway system more than a year earlier, as the pet and mascot of the men who were excavating a new subway entrance at the intersection of Bleecker and Elm (now Lafayette) Streets.

According to the New York Sun, Nellie was not a mutt, but rather “an Irish setter of patrician birth and aristocratic connections.” Here is the first Subway Nellie’s story.

The subway station for the IRT Lexington Avenue line at Bleecker and Elm was still under construction when Nellie arrived sometime around January 1903 (give or take a few months). As a reporter for the Sun stated, it was “hard luck and a Bohemian temperament” that brought her “hungry and bedraggled” to the subway, where she met night watchman Ignatius Connelli.

Ignatius had just lost his own dog to murder by food poisoning, so when Nellie began rubbing up against him and wagging her beautiful tail, he took her in, fed her, and introduced her to a life “approaching respectability.”

Although Nellie was Ignatius’ pet, the workmen all took a fancy to her. As the underground station gradually formed, she made a cozy corner where she could while away the hours. The men often shared their food with her, but if what they provided wasn’t enough to satisfy her, she would visit her generous friends at police headquarters or among the police reporters in front of their offices at 301 Mulberry Street.

Subway Nellie spent a lot of her free time with her policemen friends at Police Headquarters at 300 Mulberry Street, pictured here in 1910, about four years after the police had moved to their new home on Centre Street.

Everyone in the neighborhood came to know and love Subway Nellie. They all took delight in her daily greetings, which consisted of joyous barks and furious tail wagging. The smart Irish setter knew exactly who her friends were and avoided anyone who didn’t meet the friendship criteria.

Dog catchers who rounded up stray dogs (and cats) for the SPCA’s shelter on East 102nd Street were among Nellie’s enemies. However, they could never get within a block of her. Even if she were caught off guard, there was always a friendly cop around to yell, “Scoot, Nellie!” whenever these men appeared.

The dog wardens tried all sorts of tricks to catch her, but Nellie’s loyal friends always came to her rescue by warning her of dangerous traps and ambushes. Had she been caught, Subway Nellie would have been sent to the gas chamber, courtesy of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

In 1855, a law was passed requiring all stray dogs in New York City to be captured and placed in the dog pound at the foot of the East River. If unclaimed within 24 hours, the dogs would be drowned in the river. Those dogs who were too big to be drowned were beaten to death with a club. This barbaric practice came to an end in 1895, when the SPCA took over dog and cat control–but even Nellie knew it would still cost her life if she was captured by the dog catcher.

Soon after her arrival at the subway station, Nellie gave birth to several puppies (some news articles say she had three puppies while others say she had seven pups). The pups grew and thrived in the subway entrance and played with everyone who came to call on them.

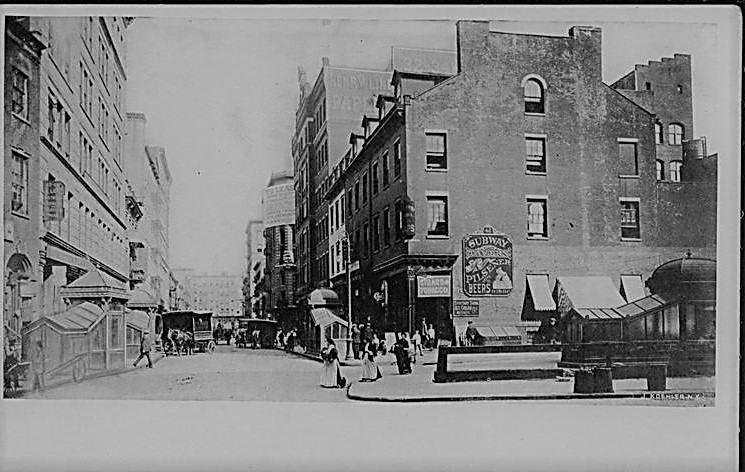

Construction started on the first IRT line in 1900. The Bleecker and Elm Street station (entrances pictured here on the far left and right), opened on October 27, 1904. The large brick building in the background is 42 Bleecker Street, where Joe Johnson operated the Subway Tavern from 1904-1906 and Fred Sauter had his taxidermy workshop from 1906-1947.

Nellie “Goes Mad” After Fight With Feline Bar Fly

One night in July 1904, Nellie walked into a saloon in the Bowery. Wagging her tail in a friendly manner at the bartender, she lay down on the floor and rested. Everything would have been fine, had Nellie not encroached on the territory of a member of the feline species.

A fight ensued between canine subway mascot and feline bar fly — according to the Sun, the cat insulted Nellie, “saying to her things which no lady, least of all a mother, could pass in silence.” Nellie received a lacerated nose in the fight, and she also suffered from a torn tail and wounded leg. The poor cat did not fare any better; in fact, he succumbed to his injuries and was buried the next day “with some regret.”

No one knew for sure whether the cat fight caused Nellie to become rabid (back then they called it going mad), or, as a story in the New York Press suggested, she went mad because the workers took all her puppies home with them. But a few days later she burst through the swinging doors of a saloon at Mulberry and Houston Streets with “eyes redder than her hair and froth (that) dripped from her mouth.” She leaped toward the bar, causing the bartender and a dozen male patrons to run into the street yelling for help.

Nellie exited the saloon and continued on her rampage. She galloped toward her old news reporter pals sitting outside their offices at 301 Mulberry Street, and then she headed down Mulberry and Houston Streets. Nellie finally came to a stop in front of a new 12-story loft building at 166-168 Crosby Street (the large building extended through to 632-634 Broadway).

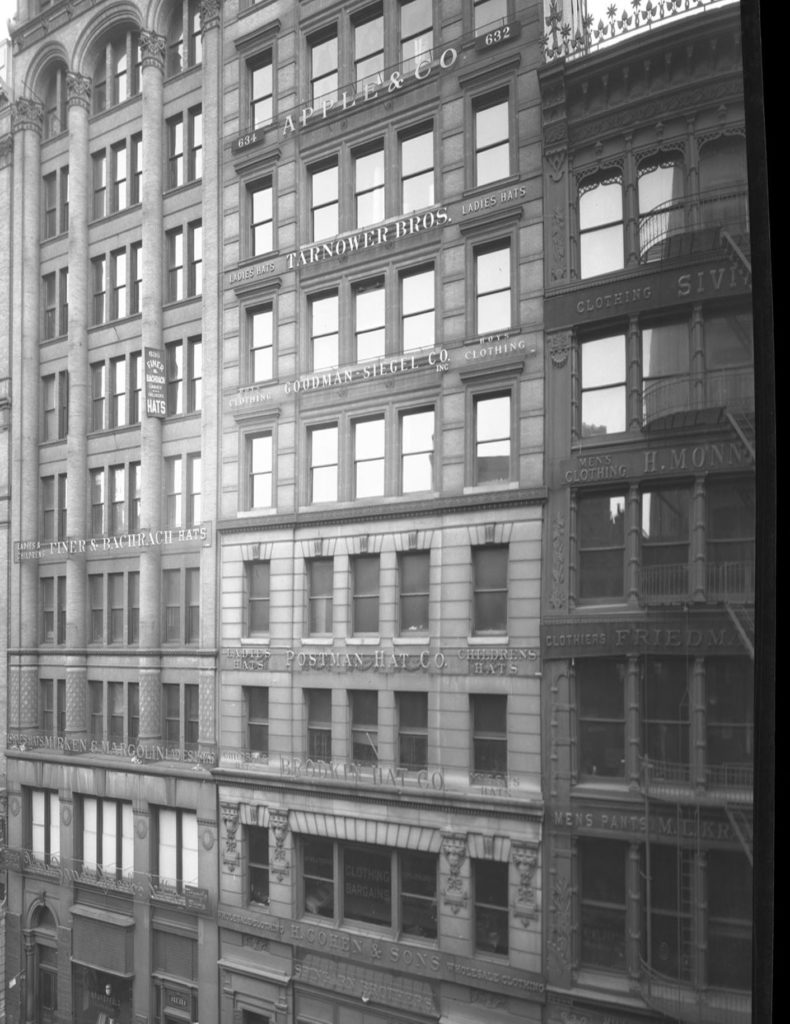

The large 12-story store and loft building at 166-168 Crosby Street (through to 632-634 Broadway) was built sometime just prior to 1900, which is when Augustus D. Juilliard, a highly successful and wealthy dry goods merchant, purchased the building for $800,000 from Henry Corn. Following Juilliard’s death in 1919, the bulk of his and his wife’s property, including an estate in Tuxedo Park, NY, and numerous properties throughout Manhattan, were sold to benefit a fund “for the advancement of music in the United States.” The renowned Juilliard School of Music opened in 1920. Photo, New-York Historical Society.

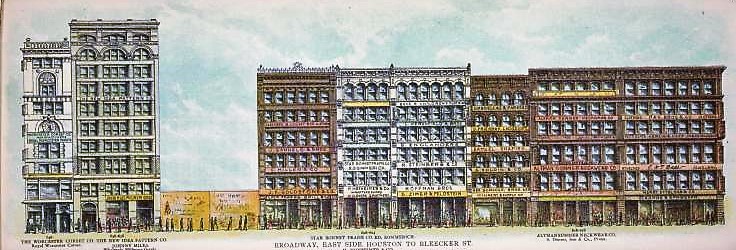

In this 1899 illustration of Broadway between Houston and Bleecker Streets, there are vacant lots at 632-634 Broadway. (The lots had been occupied by Calvin Witty’s carriage warehouses, where he sold all kinds of buggies, carriages, and harnesses in the 1860s and 1870s.) The two lots were sold at auction on October 12, 1898. In 1900, Augustus Juilliard purchased the new 12-story building on this plot. It was in this building that Subway Nellie lost her life.

At 166-168 Crosby Street, Edward Peters of Brooklyn was lowering a new boiler into the basement through an excavated shaft under the sidewalk. He kicked at Nellie as she charged him, burning both of his hands on a hot steam pipe in the process.

Nellie also burned herself on the pipe, causing her to tumble down the shaft and into the cellar, where James McGlynn was working. She sprang at James, but he was able to climb to the roof of the cellar on a network of pipes.

Back on the street, Edward began shouting “Police! Help! Mad dog!” as hundreds of people gathered around to watch all the action. Policemen John J. Keyes and Thomas Moffatt of the Mulberry Street station came running to the scene with their revolvers drawn. Then they both climbed down the scaffolding into the basement.

Officer Keyes fired five shots, but none of the bullets had any effect on Nellie. Then Officer Moffatt emptied his revolver (he was injured when the hammer flew off his gun). Nellie howled in pain but she remained standing.

Moffat secured a third revolver from a watchman, and it was with this gun that he was able to dispatch the rabid dog. All in all, twelve shots were fired at poor Nellie. One went through her head, another through her heart.

When Ignatius Connelli heard about what had happened to Nellie later that day, he picked up her puppies and sat with them for hours, “holding the wriggling little things close to him” in order to comfort them as they howled for their momma dog to come home.

An article in the New York Press said that Nellie was buried in the tunnel, but another article in the Sun said she was carted away to the garbage dump. I have a feeling that if Fred Sauter had opened his taxidermy workshop at 42 Bleecker Street two years earlier, Ignatius would have had her body stuffed as a lasting memory of his beloved dog.

The Anthony Lispenard Bleecker Farm

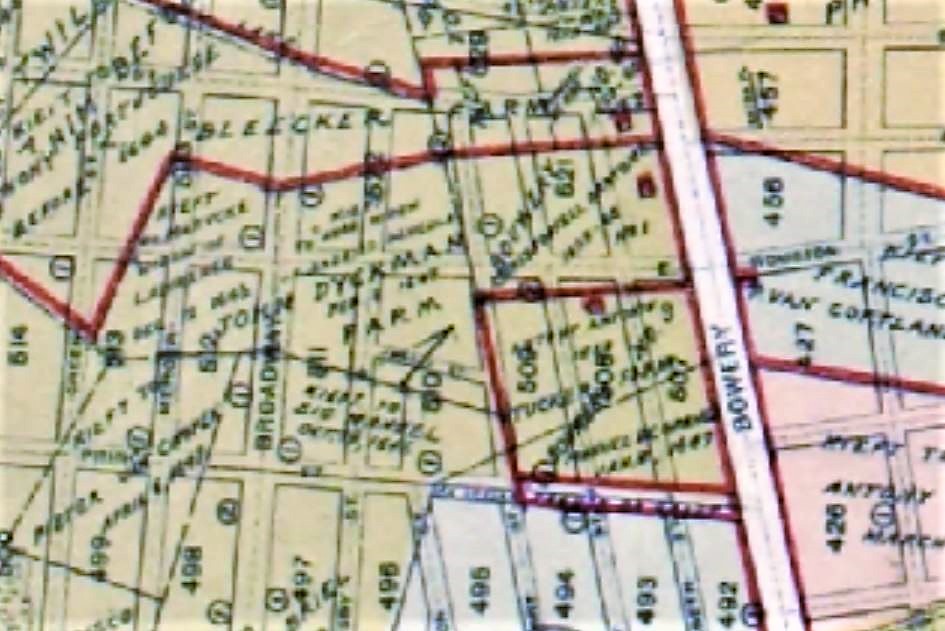

Bleecker Street is named for Anthony Lispenard Bleecker (1741-1816), a prominent banker, merchant, and auctioneer who owned a large, irregularly shaped farm west of the Bowery (the red boxed-in area at the top of this map of original grants and farms).

Subway Nellie lived and died on what had once been a part of Peter Stuyvesant’s farm, also known as West India Company’s Bouwery #1, the Great Bouwery, or Stuyvesant’s Bouwery. Director Wouter Van Twiller, who served as governor of New Netherland from 1633 to 1638, acquired the 250-acre bowery in 1633. The large farm was afterwards granted in small parcels to several free African-Americans (these parcels were called “negro patents” in historical documents).

Anthony Lispenard Bleecker was the son of Jacobus Bleecker and Abigail Lispenard. He worked as a shipping merchant, stock broker, and real estate auctioneer, eventually becoming one of the wealthiest and most powerful men in eighteenth-century New York.

One of the parcels east of Broadway was granted to Manuel de Ros, alias, “Swager.” A parcel west of Broadway was granted to Wolphert Webbers. Nicholas Bayard later acquired both parcels, which he then conveyed to Stephen N. Bayard. A farmhouse that was still standing west of the Bowery and south of today’s Bleecker Street in 1799 was probably constructed by Stephen Bayard.

In September 1790, Stephen Bayard conveyed the 23-acre farm John Lawrence and Effingham Embree. They sold the land to Anthony Lispenard Bleecker on December 31, 1791.

Bleecker did not reside at the farm; he lived at 74 Broadway, across from Rector Street, where the large Bleecker family had lived for many years.

Anthony Bleecker died April 26, 1816, and was buried the following day in the family vault he had purchased in 1790 at the Trinity Church Cemetery.

Up until recently, the ground floor of the loft building where Subway Nellie lost her life was home to a PetSmart. The pet store has since closed.

What a sad ending. And the irony of the PetSmart! I feel like this is a very “New York” story – beautiful and eccentric and brutal, with a lot of personality. Thanks so much for sharing it.