This is not Jerry of the Greenpoint Avenue police station, but I imagine he may have looked like this–especially with those sad eyes and stubby tail.

In Old New York, almost every police station had a least one canine mascot in addition to one or more feline mousers. Although the cats seemed to get most of the press in those days, every once and a while a story about a police station’s mascot dog would appear in the paper. Oftentimes, the news was not good.

According to the New York Sun (if you see it in The Sun, it’s so), in most cases, these dogs were “the outpouring of the city streets, speechless waifs, sprung from the unknown and carried by fate straight up the green-lighted steps and open doors of a precinct station house.”

Jerry, the small, otherwise nondescript police dog of the Greenpoint Avenue police station in Brooklyn, was such a dog.

Jerry arrived on the steps of the Greenpoint Avenue police station during a late winter storm in March 1899 (give or take a year). Here’s how one patrolman described the event on the day the poor dog “was murdered in cold blood”:

“It was one of those March blizzards, those nasty things that come just when a man is all set on seeing the grass and leaves and spring again, and the wind was snitching up from the East River at an awful clip. The snow was so thick that I don’t think that the cop would have seen Jerry, if he hadn’t a-kicked against him that night. The dog yelped a bit and then the cop reached down and picked him up and brought him right in the corner by the stove. We gave him some whiskey and let him rest by the stove and pretty soon that stumpy block tail of his began to whack the floor.”

According to the patrolman, the day sergeant was a well-read man who read Martin Luther and Shakespeare. The sergeant told the men that he had read a story about a dog named Jerry that looked a lot like the little waif dog. “So Jerry he was, and Jerry he came to be all over here.”

Over the next few years, Jerry became very attached to the men assigned to what was then called the 61st police precinct. He loved hanging out in the yard at the police station and going on post with the officers. “Every cop on post was proud to count himself as Jerry’s friend,” the patrolman told the news reporter.

Jerry knew all the precinct boundaries, and even though he often swam in the East River (he was “a powerful little swimmer”) and loved to romp through “the woods of Masbeth” (Queens), he always returned to the station house. “Say, you couldn’t have dragged him out of this precinct with a cart and horse,” the patrolman said.

Before I tell you about the sad fate of Jerry, let’s explore the history of the neighborhood and building that he called home.

The Greenpoint Avenue Police Station

The Greenpoint Avenue police station as it looked in 1900. Jerry the dog is somewhere nearby…

“When one alights from a car at Greenpoint and Manhattan Avenues the first thing the eye sees is the Greenpoint Avenue police station. From external appearance, unless one is familiar with the neighborhood, the building would never be taken for a station house. A stranger would come to the conclusion it was an apartment house with a peculiar entrance.”— Brooklyn Daily Standard Union, September 28, 1918.

In 1853, construction began on the Greenpoint & Flushing Plank Road between the new Greenpoint Ferry on the East River in Brooklyn and the Calvary Cemetery in Queens. The road, also once known as L Street when all the streets in the neighborhood were named for letters of the alphabet, was opened to traffic in 1854.

In 1859, the first Greenpoint police station—then one of only three police sub-stations in the City of Brooklyn—was established on the corner of Greenpoint Avenue and Franklin Street. The City of Brooklyn rented the building from Josiah Carver (secretary and treasurer of Brooklyn Gas Light Co.) for $275 a year.

During those early years, the police station was known as Police House No. 7 (it was in the 7th Precinct of the Metropolitan Police District, which was established on April 15, 1857). The first captain at this station was John Stillwell, who was responsible for supervising a 12-man force.

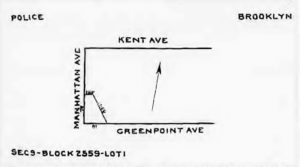

In August 1861, the City of Brooklyn purchased a large lot on the northeast corner of Greenpoint and Manhattan Avenues from Neziah and Mary Bliss. The city paid $1500 for the trapezoidal-shaped lot.

The City of Brooklyn purchased this trapezoidal lot from Neziah Bliss in 1861.

That same year, a large, three-story police station at 145 Greenpoint Avenue was constructed on the site. Behind the police station stood the 17th Ward bell tower of the newly incorporated (1857) Eastern District Fire Department.

The policemen were reportedly responsible for ringing the 5,000-pound bronze bell to alert the firemen of nearby fires.

The Greenpoint Avenue police station in 1923, one year before the city sold the building at auction.

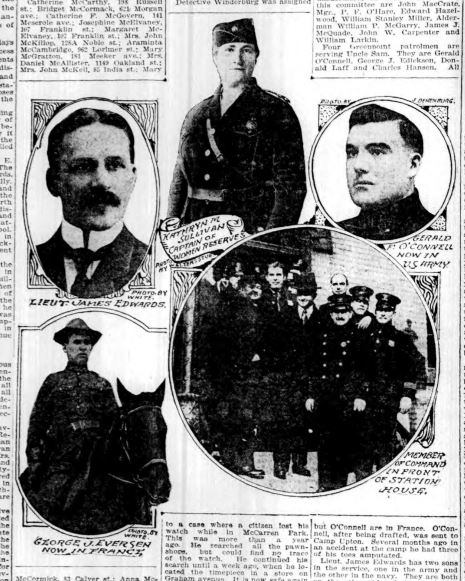

Over the next fifty years, the precinct was re-designated as the 61st (1899-1913) and the 161st precinct (1914-1923). By 1918, when Charles E. Lee was captain, the precinct had the largest women’s police reserves in the city, with more than 300 members under the leadership of Captain Kathryn Sullivan.

In 1920, a city report concluded that the Greenpoint Avenue station house and jail was a “wretched building” and “one of the worst in the borough.” Although money was budgeted to construct a new building on the site, Police Commissioner Richard Enright decided to sell the old building and construct a new building on the corner of Messerole and Lorimer Avenues for a new 51-A Precinct.

A few police officers of the Greenpoint Avenue police station in 1918, including Kathryn Sullivan of the women’s reserves. That year, several officers were overseas taking part in World War I.

In 1924, the station houses at Greenpoint Avenue and 43 Herbert Street were shut down, and all of the records and property from both stations were transferred to a new precinct building for the 51-A Precinct at 100-102 Meserole Avenue (still standing and now home to the 94th Precinct).

The old police station and stables at 43 Herbert Street, built in 1891-92 and closed in 1924, is still standing. Today it is occupied by condos.

The city leased the old Greenpoint Avenue station to the nearby Church of St. Alphonsus for use as a parochial school for about a year. In June 1926, the building was auctioned at a public sale held in the Aldermanic chamber of Brooklyn’s Borough Hall.

The old police station served as headquarters for the American Legion from the 1930s to 1950s and was eventually demolished.

Today the site is occupied by a New York Sport Club and a one-story McDonald’s restaurant.

Today the site of the old Greenpoint Avenue police station is occupied by a trapezoid-shaped McDonald’s restaurant and New York Sports Club.

Neziah Bliss, the Founding Father of Greenpoint

The man who sold the large trapezoidal lot on Greenpoint Avenue to the City of Brooklyn in 1861 was Neziah Bliss, considered to be the main person responsible for transforming Greenpoint from a farming community to an urban center focused on shipbuilding.

Born in Hebron, Connecticut, in 1790, Bliss moved to Philadelphia in 1811, where he formed a business partnership with Daniel French to build steamboats—then in high demand following Robert Fulton’s successful sailing of the Clermont a few years earlier. After moving to New York City in 1827, he went into business with Eliphalet Nott and established an iron works (Novelty Iron Works) at the foot of East 12th Street, where they produced steam engines and steamboats.

Neziah Bliss, the founding father of Greenpoint, Brooklyn

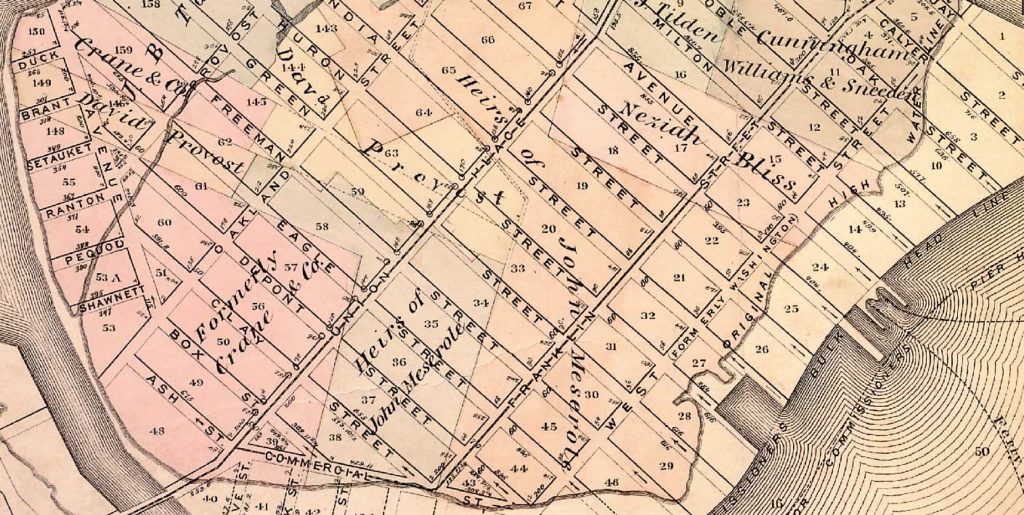

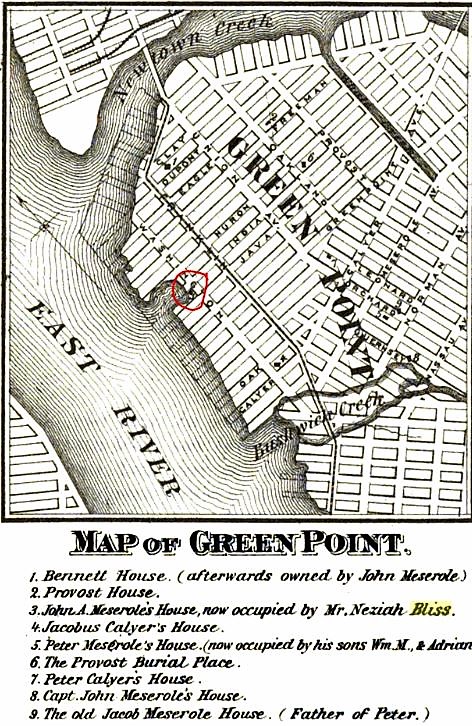

In 1832, Bliss and Nott expanded eastward—directly across the East River, to be exact—by purchasing 30 acres of the John A. Meserole and Peter Meserole farm in what was then called Green Point (two words). The following year, Bliss bought at auction the farmland of David Provost in the northeast part of Green Point along the Newtown Creek.

Bliss’s land acquisition continued through his marriage to Mary Meserole, the daughter of John A. Meserole, which allowed him to obtain even more land along the shores of the East River. In 1834, at his own expense, Bliss had all his land surveyed and mapped into streets that aligned and connected with the villages of Williamsburgh, Bushwick, and Hunters Point.

Bliss later ventured north of Newtown Creek to purchase the Hunters Point Farm and what was then called Dutch Kils, which he renamed Blissville (and is now a part of Long Island City).

In order to overcome Greenpoint’s natural barriers and encourage development in Greenpoint, Bliss took several steps:

- In 1838 he paid $800 to build a foot bridge over the Bushwick Inlet from the intersection of present-day West and Quay Streets to about North 14th Street in order to connect Greenpoint with Williamsburgh (back then the inlet extended just beyond today’s Nassau Avenue).

- He championed the opening (1839) of the Ravenswood, Green Point, and Hallett’s Cove Turnpike (along what is now Franklin Street) to connect Greenpoint with Williamsburgh and Astoria, Queens.

- In 1850 he secured a lease from New York to establish regular, dependable ferry service from the foot of Greenpoint Avenue to East Tenth Street (and later, to East 23rd Street) in Manhattan. (Until then, the only way to get from Greenpoint to Manhattan was by a little skiff owned by Alpheus Rollins, who charged three cents per passenger each way.)

- He built the first Blissville Bridge (today the Greenpoint Avenue Bridge.

This 1874 Brooklyn farm map shows all the land owned by Neziah Bliss, including the old Meserole and Provost farms.

Neziah and his wife, Mary, lived in John A. Meserole’s house, which stood until 1875 near the East River on Washington Avenue (now West Street) between India and Java Streets (marked by the red circle).

According to the Museum of the City of New York, this 1848 daguerreotype depicts the “First Meserole House” in Wallabout, Brooklyn. Could this have been John A. Meserole’s house in Greenpoint? Perhaps…

By 1840, Greenpoint had become a booming shipbuilding town filled with houses, churches, schools, and shops (but no police station yet). Before Bliss died in 1876 at the age of 86, he was a very wealthy and well-known man in the town he established.

The End of Poor Greenpoint Jerry

By 1902, Jerry had gone from a good naïve pup to a cranky dog who had acquired strong likes and dislikes. For example, when he was a puppy he enjoyed snapping and snarling at “tramps” on the street. A few years later he was snapping at almost every poorly-dressed man or woman who visited the police station. Eventually, he greeted every visitor with suspicion.

So when a solemn Police Inspector Thomas L. Druhan paid a visit to the station in October 1902, Jerry took offense and began snarling at the man who was frowning at him. The inspector took one good look at Jerry’s white, pointed teeth and shouted angrily to the desk sergeant, “You had better get this dog out of the way before I do.”

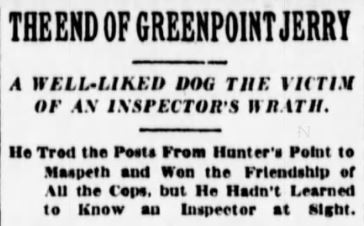

The story of Jerry’s demise made the headlines in several newspapers, including the New York Sun.

Although Jerry obeyed the sergeant’s command and ran to the back room, Druhan decided that the dog was vicious and ordered the poor little dog to be killed. Three days later, Jerry looked into the tearful eyes of the patrolman who held the revolver and wagged his tail a few times with hopes of getting a return smile that never came.

“I suppose that it is foolish to get a thinking of a dog that way,” said one of the patrolmen. “But if you’d been stationed here, like me, all the time that he was here you might understand. He was such a little fellow, and he had so many monkey tricks; he was such a mighty good fellow, was Jerry, that we all seem sort of lost without him now. It seemed hard to all of us that Jerry, who knew more than a good many men, should have to die like a dog.”