On April 11, 1912, the RMS Carpathia departed from Chelsea Piers in New York City for Fiume (present-day Rijeka, Croatia), carrying about 740 passengers. The ship never reached its destination on this particular departure.

Just after midnight on April 15, 1912, Carpathia‘s wireless operator, Harold Cottam, received some messages from Cape Cod stating they had private traffic for the Titanic.

Cottam relayed the message to the Titanic. In response, he received a distress signal stating the ship had struck ice and was in need of immediate assistance.

After failing to get a response from some officers on the bridge, Cottam ran to the captain’s cabin to awake Captain Arthur Henry Rostron.

The captain immediately sprang into action and ordered the ship to turn around and travel full speed toward the troubled Titanic. Rostron later testified that the Titanic was 67 miles away and that it took the Carpathia—reaching maximum speeds up to 17.5 knots —three and a half hours to reach her.

As the Carpathia was making its way toward the Titanic, Rostron ordered the crew to prepare hot drinks and soup for the survivors, prepare public rooms for use as dormitories, and shut off all the ship’s heating and hot water in order to make as much steam as possible for the engines.

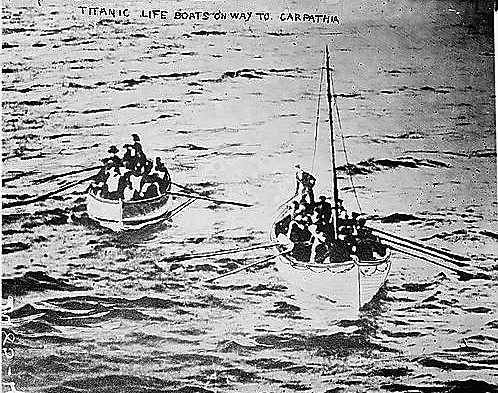

The Carpathia arrived at the scene about one and half hours after the Titanic went down, claiming more than 1,500 lives.

The ship took on the 705 human and 3 canine survivors who had made it to the 20 lifeboats. Survivors were taken to the dining rooms and given blankets and coffee. When the last survivor was picked up at 9 a.m., the Carpathia headed toward Chelsea Piers in New York City.

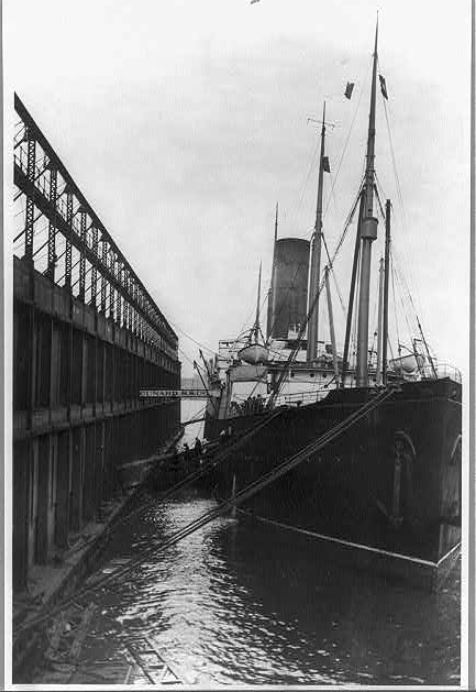

Slowed by icy conditions and storms and fog that lasted for two days, the Carpathia finally arrived at New York’s Chelsea Piers at about 9:30 p.m. on April 18. According to the New York Times, more than 40,000 people were anxiously waiting for the rescue ship to arrive, including about 2,000 people who stood on Pier 54 (friends and family, medical professionals, and government officials) and another 40,000 who lined the Battery and Chelsea Piers.

The Carpathia first sailed to Pier 59, the berth for the White Star Line, to drop off the empty lifeboats. It then sailed back to Pier 54, the Cunard Line pier, to allow the Carpathia passengers and Titanic survivors to disembark (the Carpathia passengers were let off first because Captain Rostron knew there would be mayhem when the survivors appeared).

As the first survivors walked off the ship, thousands of people began to shriek and sob with joy and grief.

Carpathia Crew Is Rewarded

To honor the Carpathia, the Titanic survivors presented the crew and officers with bronze and silver medals. Captain Rostron was also knighted by King George V, and was a guest of President Taft, who presented him with a Congressional Gold Medal at the White House.

Oh yeah, one more thing: Captain Rostron also received a ship’s mascot kitten for his ship. Here’s how it happened:

According to numerous news reports, on May 31, 1912, Captain Rostron and several other officers from the Carpathia were attending a variety show at New York City’s Winter Garden Theatre when they were spotted by actor/comedian Al Jolson. When Jolson told the audience that the captain and his crew were seated in box seats to the right of the stage, every person stood up and began cheering and shouting for him to make a speech. It was reported to be “one of the most remarkable demonstrations ever witnessed in that theatre.”

Normally a very quiet man, Captain Rostron tried to shy away while the band played “The Star Spangled Banner” and “God Save the King.” The captain finally stood up and gave a very short speech in which he said that he and his crew truly appreciated all the honor that they had received in America.

Following this grand reception, a few members of the Winter Garden Theatre Company decided to give Captain Rostron a small black cat in order to bring good luck to his ship. I have no idea where the cat came from; news accounts only state that the kitten was three months old and wore a collar made of rosebuds.

A week after the performance, just before the Carpathia set sail for London from the Curnard pier, Miss Grace Kemble and Miss Irene Claire—both chorus girls with the theater company—presented Captain Rostrand with big kisses and a tiny kitten. (Reportedly hundreds of unmarried women gave the captain a kiss, so the kitten made Grace and Irene stand out from the crowd.)

While the captain was basking in the attention, one jealous third mate reportedly lifted the kitten to inspect him for any white hairs or whiskers (the presence of even one white hair or whisker on an all-black cat was considered a bad omen to sailors.) Not finding a single white hair, the third mate heaved a sigh of relief and patted the new mascot on his arched back.

The captain assured the women that the kitten, who was later named Captain, would be provided with luxurious quarters in his cabin.

Captain, the Carpathia Mascot Cat

In July 1912, the New York Evening World reported that Captain the cat had returned from his first trip across the Atlantic under the command of Captain D. Dow of the Carmania (Captain Rostron had to skip the return trip to New York in order to participate in the Titanic inquiry in London). According to the officers, crew, and passengers, Captain had conducted himself “like an old salt from the time the ship left New York until her return.”

In addition to holding the ship’s record for mouse assassinations, Captain indulged “in all the feline pastimes for which nautical cats are famous, from climbing the mast to the crow’s nest to sleeping serenely on the rail while the vessel was pitching and rolling in heavy seas.”

Captain Rostron continued in command of the Carpathia for a year before transferring to the Caronia. In later years he took command of the Carmania, Campania, and Lusitania, as well as the Aulania during World War I, the RMS Mauretania, the Ivernia, and the Andania and Saxonia. He rose to become the Commodore of the Cunard fleet before retiring in 1931.

No further mention of Captain the cat was ever made, so I can only hope that the kitty stayed with Captain Rostron as he moved from ship to ship.

During World War I, the Carpathia transported Allied troops and supplies. On July 17, 1918, while taking part of a convoy traveling from Liverpool to Boston, the ship was struck by three torpedoes from a German U-boat and sank. Five crew members were killed; the passengers and surviving crew were rescued by the HMS Snowdrop of the Royal Navy. There were no reports of a cat on board.

A Brief History of Chelsea Piers

In the early 1900s, with ocean liners like the Carpathia becoming bigger than ever, New York City began to seriously look for a solution to its passenger ship dock needs. One of the biggest challenges was that the U.S. Army, which controlled the location and size of piers, had refused to allow any piers to extend beyond the existing pier-head line of the Hudson River.

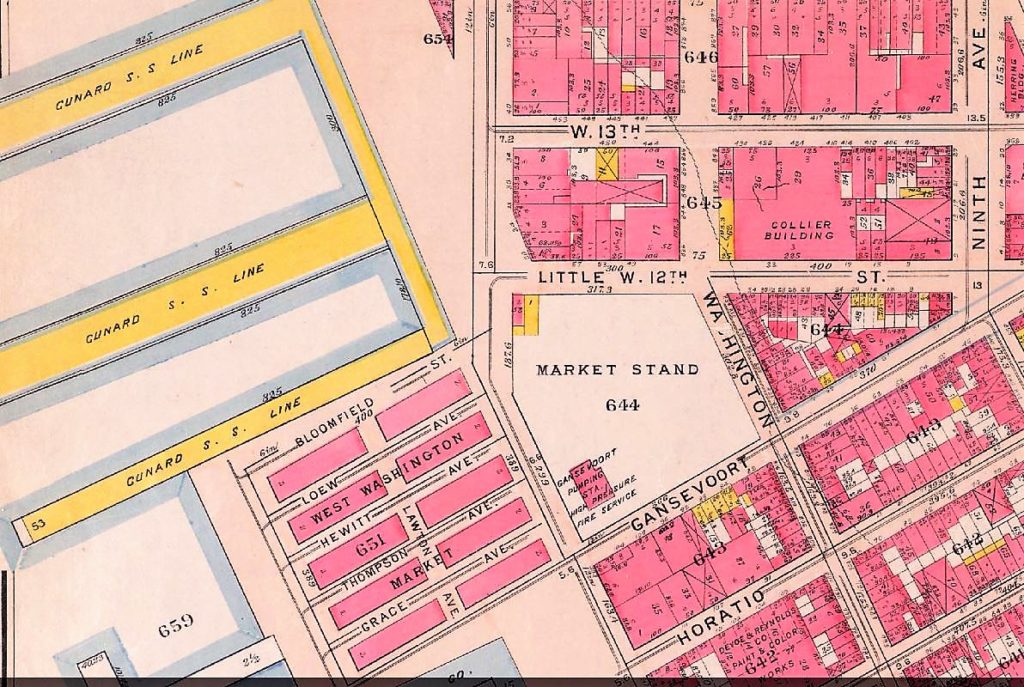

The city solved this roadblock by condemning several blocks of land that had been created with landfill during the early 1800s to extend Manhattan to what was then called 13th Avenue.

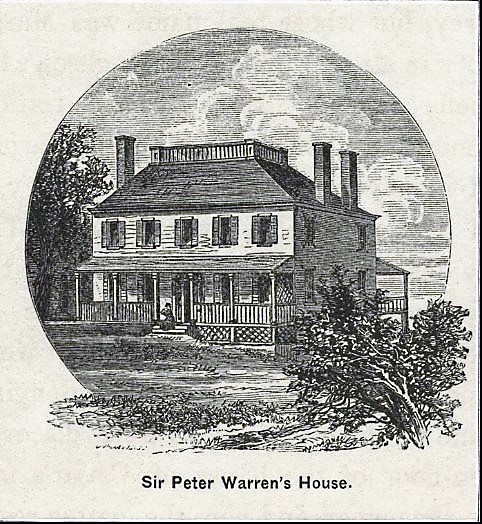

The land upon which Chelsea Piers was constructed was once part of a large 300-acre farm along the Hudson River waterfront owned by Sir Peter Warren, a Royal Navy officer of Irish descent. The Warren Farm stretched from the Hudson River to the Bowery and from Charles to West 21st Streets.

In the early 1740s, Warren built his stately home overlooking the river on the block of land bounded by today’s Bleecker, Charles, Perry, and West 4th Streets. Following his death in 1752, his estate was divided among three of his daughters; the land was further divided and sold in the early 1800s.

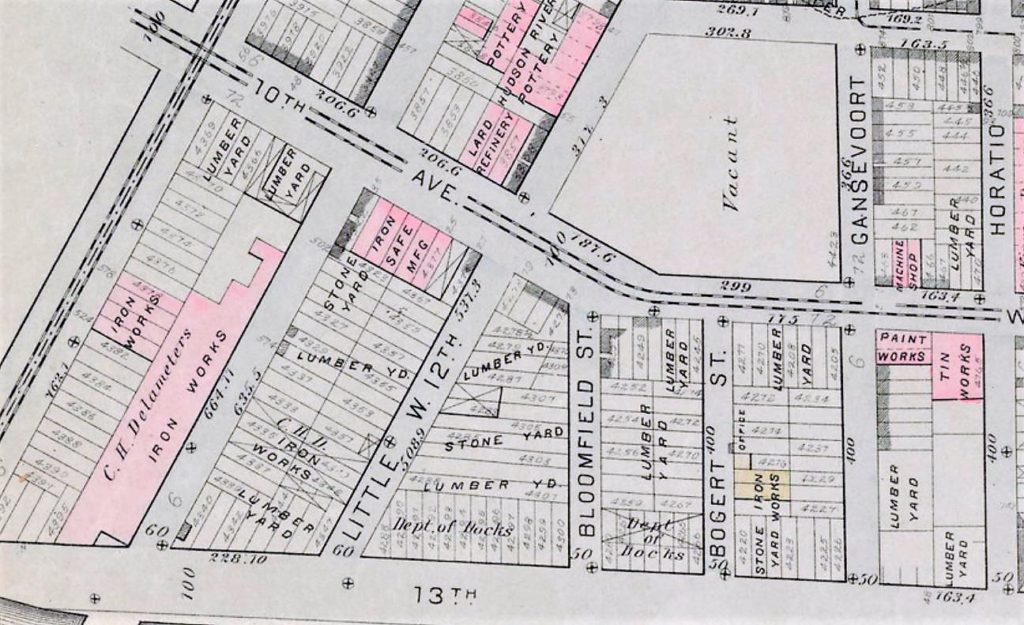

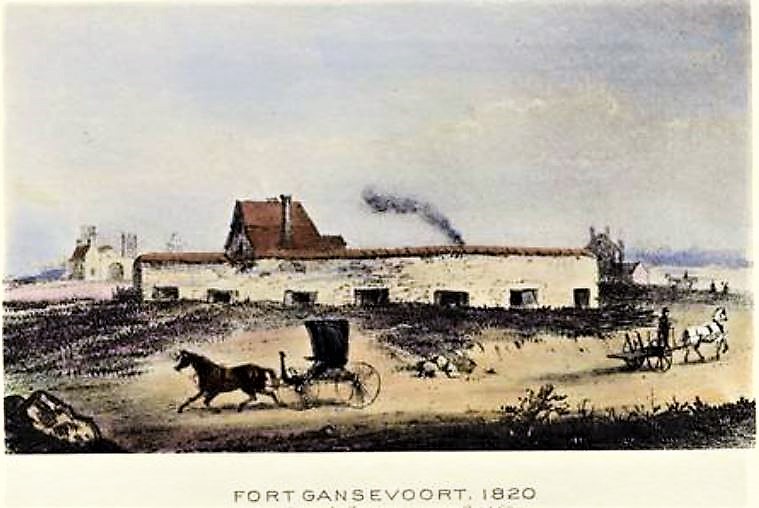

The specific area where the Cunard Line’s Pier 54 was constructed was the site of Fort Gansevoort, named in honor of Peter Gansevoort, a Revolutionary War officer. The fort, which was completed shortly after the outbreak of the War of 1812, was located at the foot of Gansevoort Street. The site of the fort was purchased by the United States on July 22, 1812, and sold to New York City in 1850.

The fort never saw action, and it was demolished about 40 years later in 1851. The city’s Sinking Fund Commissioners sold the property in 1852 to Reuben Lovejoy for $160,000, and later re-purchased it in 1862 from James B. Taylor for over $533,000 (the sale and purchase were both highly contested; the transactions reportedly involved blatant political corruption which came to be known as the Fort Gansevoort Swindle).

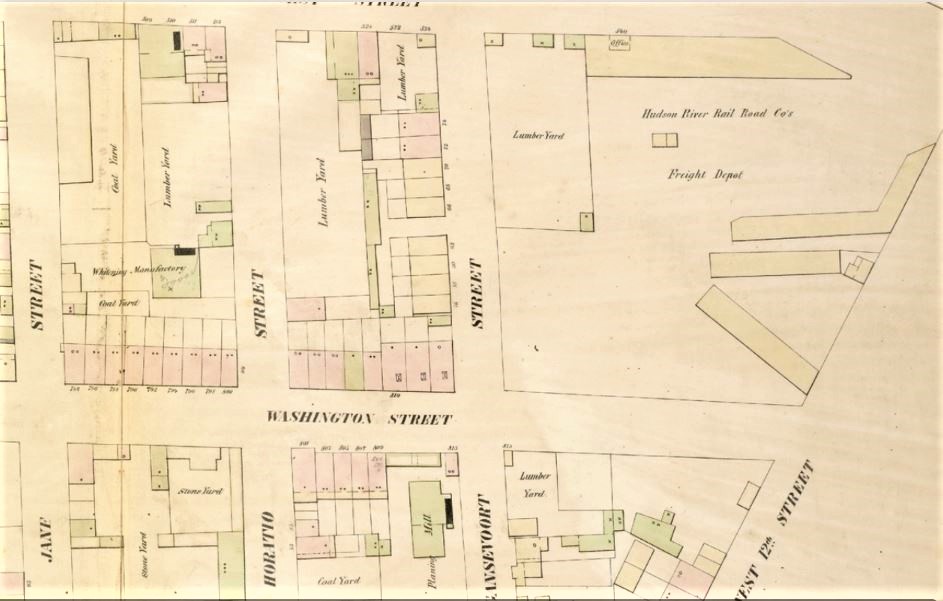

At one point during the mid-1800s the site was used as a freight yard by the Hudson River Railroad Company, prior to its purchase of St. John’s Park. The Broadway, Bleecker and Fulton Ferry Railroad later obtained a lease on the property for use as a car and stable yard (the depot and stables were removed to 23rd Street and 10thh Avenue in 1878).

In 1878, 500 property owners signed a petition to establish a new marketplace on the old Fort Ganservoort site, bounded by present-day Gansevoort, Little West 12th, Washington, and West Streets. As the New York Times reported on this site in June 1878, “the few miserable, dilapidated stables and sheds upon it and the rotten old fence surrounding it are an eyesore to the neighborhood.”

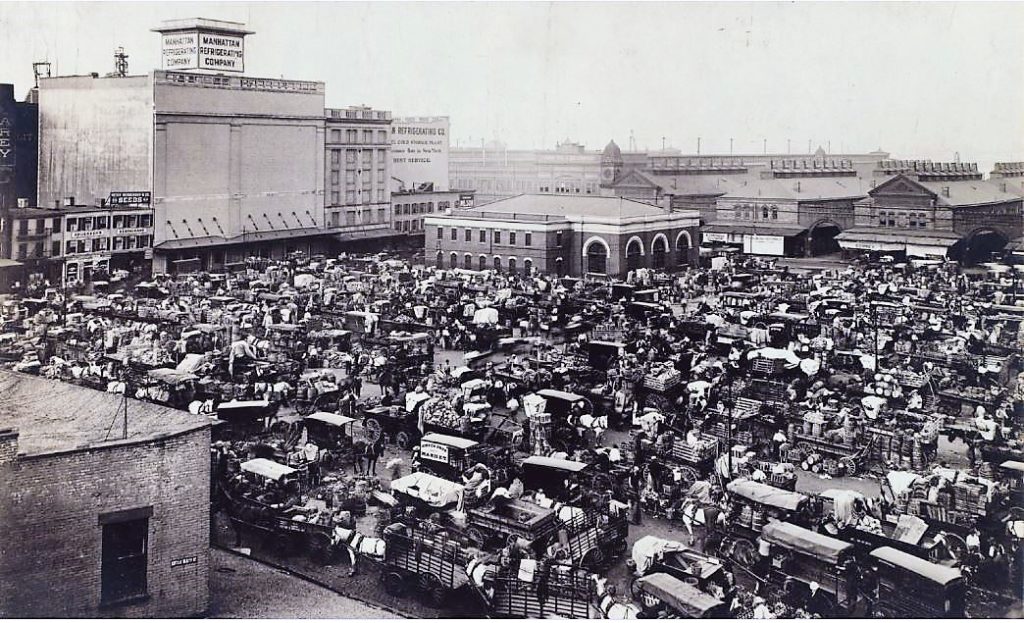

The plan was to clear, grade, pave, and gutter the land in order to create an open square where upon market wagons could assemble for the sale of farm and garden produce. After several years of talking and planning, the Gansevoort Farmers’ Market opened in 1884. Farmers paid a daily fee that went into the city’s market fund, and each wagon was assigned a station in the market.

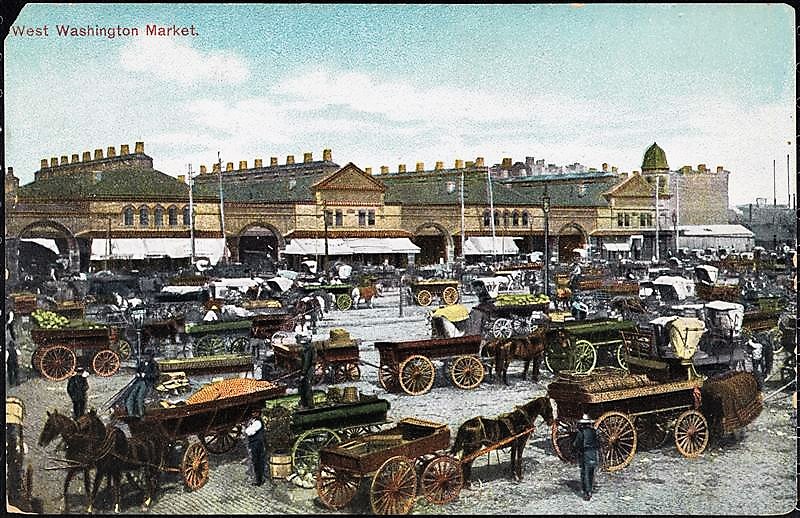

In 1889, construction was completed on the West Washington Market, which was located directly across West Street from the Gansevoort Farmers’ Market. The West Washington Market complemented the Gansevoort Farmers’ Market by offering meat, poultry, and dairy products.

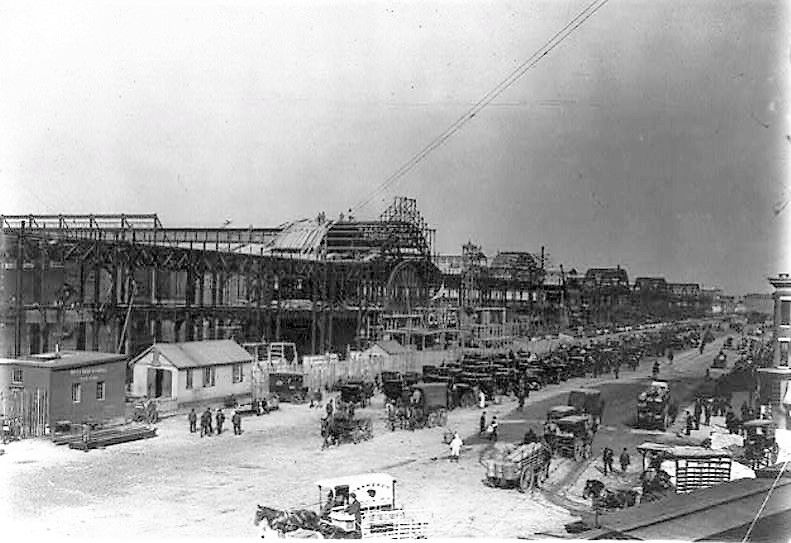

The Chelsea Piers opened in 1910, eight years after construction began. Designed by the architectural firm of Warren and Wetmore, which had also designed Grand Central Terminal at the same time, the Chelsea Piers replaced much of the former 13th Avenue with a row of grand, fireproof buildings that were constructed of steel and glass and embellished with pink granite facades.

The piers extended from the foot of West 12th Street to the West 23rd Street Ferry slips.

Today Chelsea Pier 54 is part of Hudson River Park. A rusted archway is the only remaining piece of the pier.

So interesting, as always! Such a great story. I just wish we knew what ended up happening to Captain. It’s too bad they don’t list ship’s cats on manifests – they deserve it!