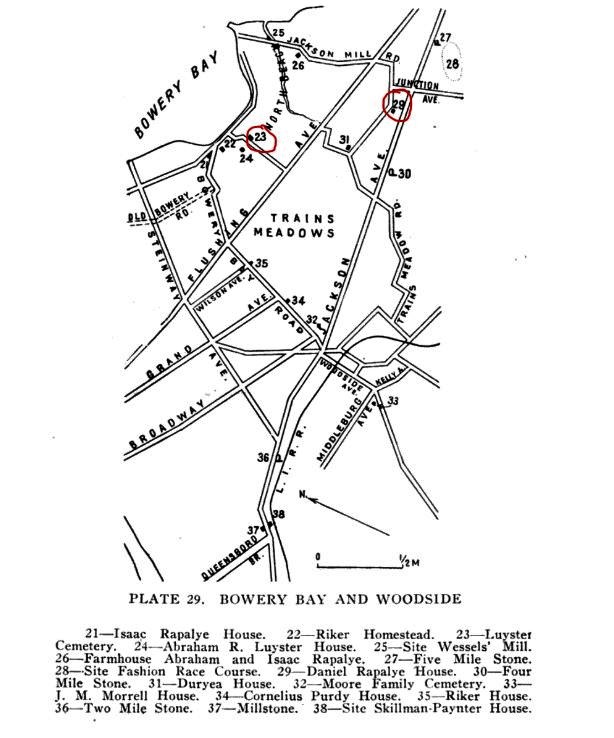

Once upon a time–around 1638–a farmer named Hendrick Harmensen took his cows from New Amsterdam and re-settled on a point of land along the Bowery Bay, where the East River and Flushing Bay meet on the northern tip of what we now call East Elmhurst, Queens. For several years, Harmensen–also known as Henrick the Boor or Henry the Farmer–was the only farmer on the north side of Long Island.

Hendrick Harmensen was reportedly killed by Native Americans during an uprising in 1643. Over the next 200 years, the land was occupied by numerous Dutch settlers and their descendants, including members of the Fish, Jackson, Luyster, Rapelye, Riker Cornell, Brinckerhoff, Schenck, Noorstrandt, Coggins, Purdy, Klock, Berrien, and Kouwenhoven families.

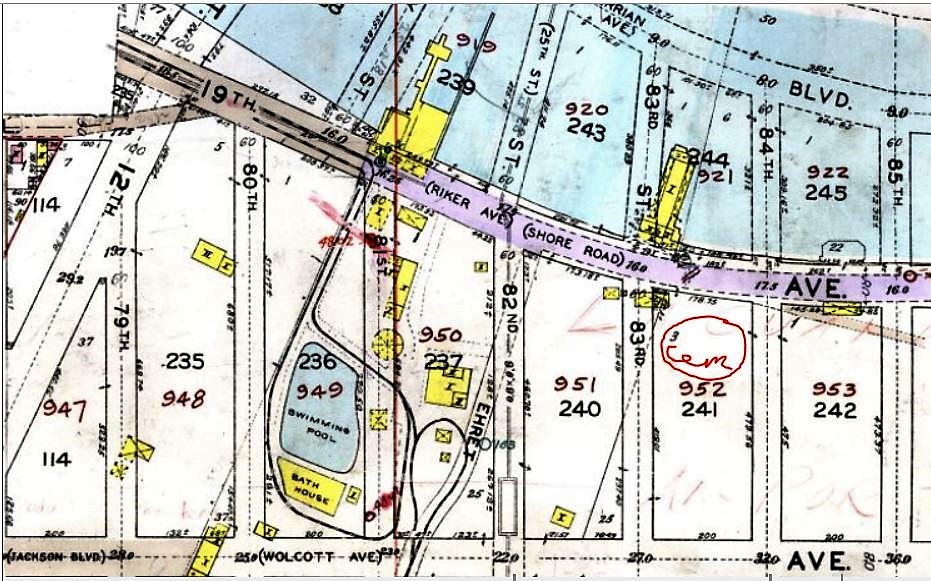

Many of these settlers were buried in a small family cemetery on a bluff overlooking the Bowery Bay. The cemetery has been buried under LaGuardia Airport for 80 years.

The Old Cemetery at Bowery Bay

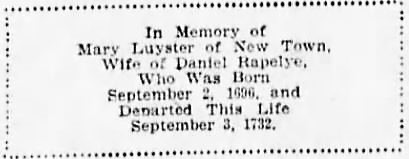

The first person buried in the old Dutch cemetery overlooking Bowery Bay was Mary Luyster, the wife of Daniel Rapelya; she was born in 1696 and died in 1732. The last person buried in this cemetery was Ann Noorstrandt, the wife of Daniel Luyster; she died in 1811 at the age of eighty-eight.

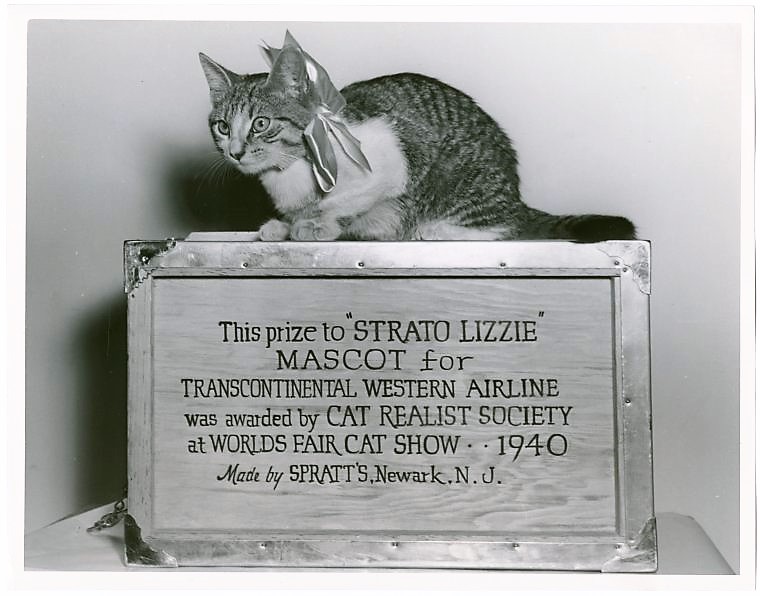

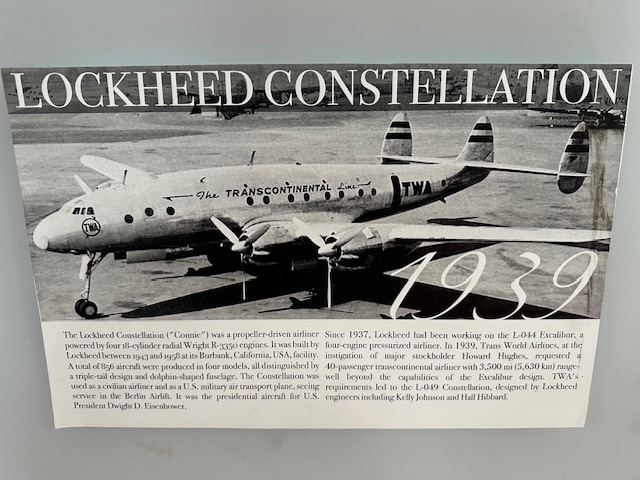

In 1939, this ancient cemetery was demolished and buried under a brand-new airport originally called Municipal Airport No. 2, aka, LaGuardia Field. One year later, a California alley cat named Stato Lizzie flew into this airport and was adopted by the pilots of Transcontinental and Western Air (TWA; later known as Trans World Airways).

Strato Lizzie Flies to LaGuardia Field

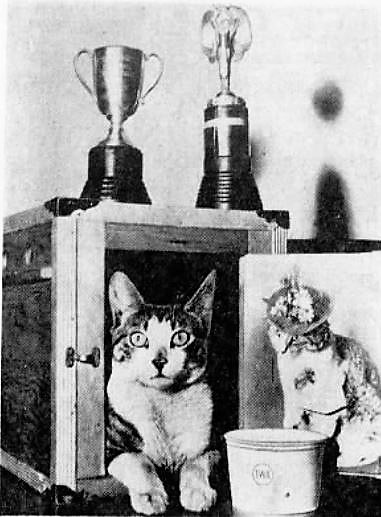

Strato Lizzie acquired her wings and began her flying career in Los Angeles. According to the story, an American Airlines pilot found her as a kitten behind an ash can in an alleyway and turned her over to W.P. Spencer, a Civil Aeronautics Authority pilot.

Spencer flew the kitty to Kansas City, and then from there she flew to the new LaGuardia Field with a message from the chief of the Kansas City office: “The kitten apparently loves flying. Therefore, I am giving it a ride to New York and back.”

Poor Strato Lizzie was tossed around like a hot potato for a while, traveling from New York to Chicago and then back to Los Angeles. Finally, when she was about six months old, the pretty kitty was adopted by the TWA pilots at LaGuardia.

Strato Lizzie made her home in Hangar No. 6. Here she received a daily meal of turkey and veal whenever she was grounded. If she wasn’t in the hangar, she could often be found near the commissary where all the food for the flights was prepared.

Sometimes Strato Lizzie would go missing for a week or more when one of the pilots took her on a transcontinental flight. (The cat reportedly crossed the continent no less than six times and traveled more than 100,000 miles during her 18-month stint as a flying feline mascot.)

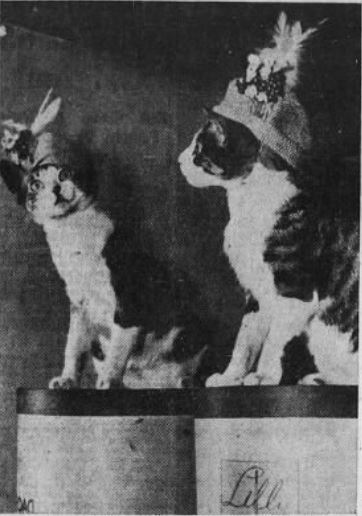

She also flew all over the country to appear in cat shows, such as the Beresford Cat Club show in Chicago, the Boston Cat Club show, and the Minneapolis Persian Cat Club show.

On January 9, 1941, Strato Lizzie went missing while being groomed for a scheduled appearance in the 39th annual championship cat show of the Atlantic Cat Club in Manhattan’s Hotel Taft. She was scheduled to appear with 121 other aristocratic cats, and a cage had been all prettied up for her with colored ribbons.

It was believed that she had been taken aboard a plane by a pilot or stewardess, and everyone at TWA hoped she would be able to fly back home in time to make an appearance at the show. Messages were sent to various TWA stations as far west as Kansas City, but no one seemed to know where she was.

As Barton Pevear, a TWA publicity representative, told the press, “Need I add that this is an unfortunate occurrence.” The show went on without its featured feline attraction.

On January 14, Strato Lizzie showed up scratching at the door of Hangar 6. The airline staff placed her under lock and key for a short time afterward.

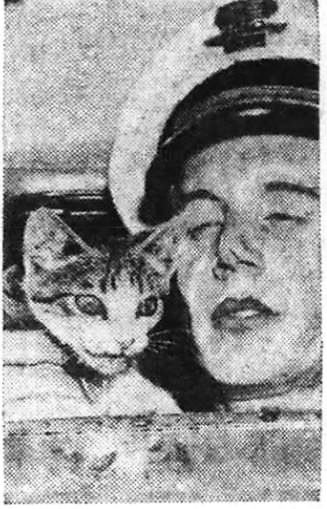

A few months after this disappearance, Paramount talent scout Hank Larner recruited Strato Lizzie for a cameo role as a Navy pilot’s cat in the movie “Forced Landing,” starring Richard Arien and introducing Eva Gabor. The night before she flew off to Hollywood, she got into a cat fight with a Persian kitten while being coaxed to “shake paws” during her “Catnip Party.”

According to a small article in several newspapers, production on the movie was reportedly held up when Strato Lizzle gave birth to four kittens on the set. I have not seen the movie, so I’m not sure if the cat ever appeared in the cameo role.

Strato Lizzie Goes Missing From LaGuardia Again

A year after her first disappearance, on January 15, 1942, Strato Lizzie went missing again. All through the day, one could hear the cries of “Here kitty, kitty” in the executive offices and hangars of TWA.

Newspapers across the country ran the story of her disappearance, and even members of the Queens County unit of the ASPCA joined in the search. During the next few weeks, many people offered to give the pilots a new cat or kitten.

On February 13, 1942, Barton Pevear announced that the company had abandoned hope for the cat’s return. During the press conference, he also announced that her successor, Strato Lizzie Jr., was officially on board. The new mascot cat was six months old and bore a striking resemblance to the senior cat. She was a gift to the airline from a New York woman who wished to remain anonymous.

Bowery Bay: From Skinny Dipping to Pleasure Seeking

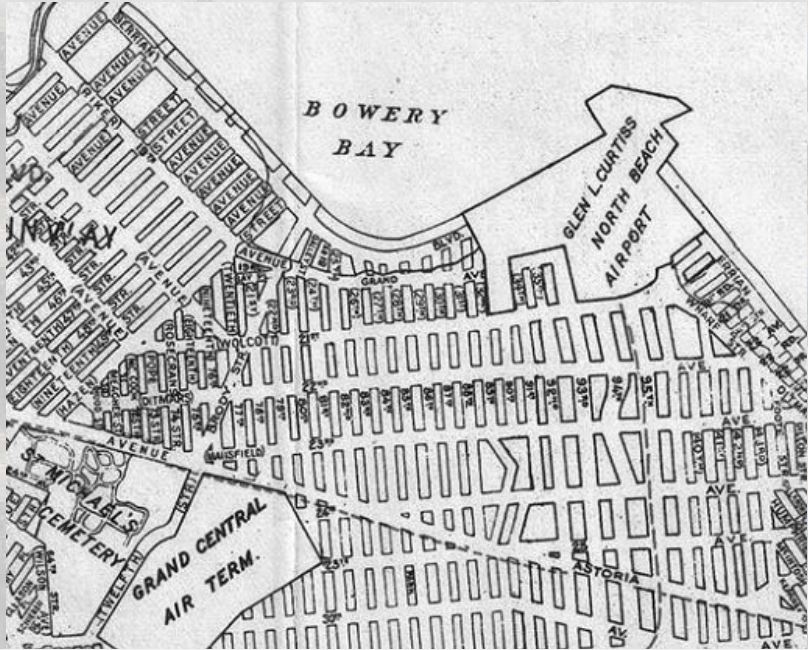

When Strato Lizzie arrived at LaGuardia Airfield in 1940, the municipal airport had been in existence for only one year. Prior to 1939, there was a seaplane base on the site that had opened in 1929, followed that same year by a small airfield of about 105 acres called the Glenn H. Curtiss North Beach Airport.

It wasn’t until October 15, 1939, that the much larger Municipal Airport No. 2 was dedicated (three weeks later, the City Council voted to rename it LaGuardia Field in honor of Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, who had pushed for a large New York City airport).

Before 1929, Bowery Bay had been a beautiful body of clear water surrounded by wooded shores and a natural bluff that made it very popular among teenage boys as the perfect place for nude bathing (much to the “disgust and annoyance of the respectable residents” who lived on the point).

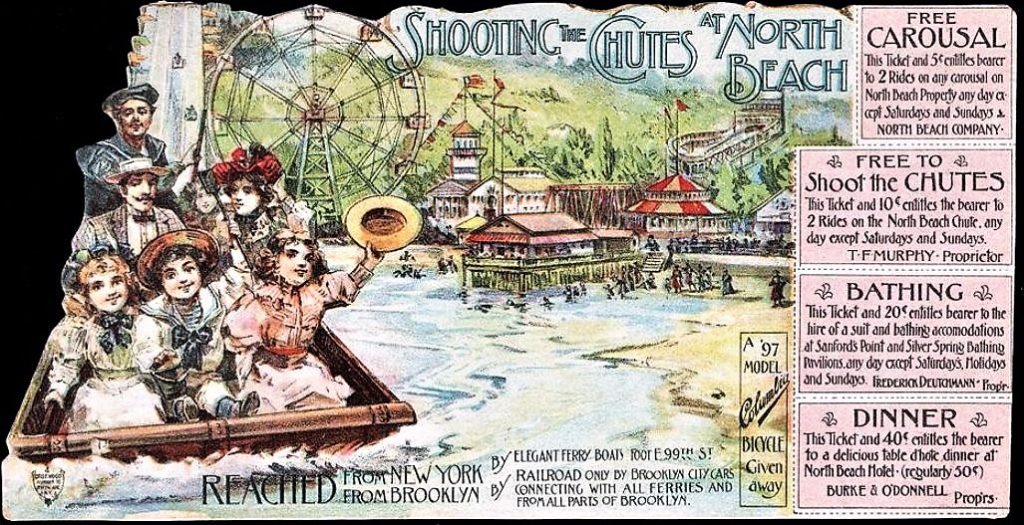

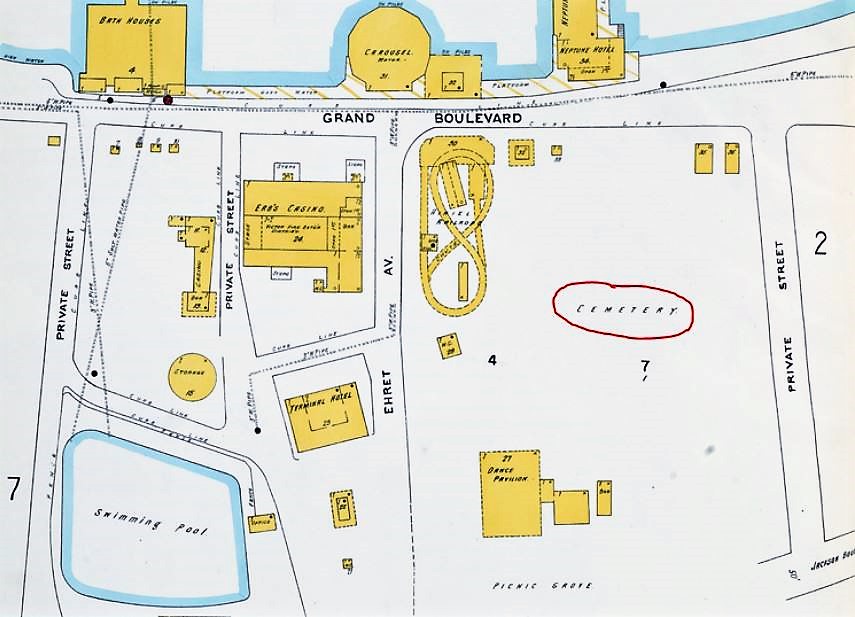

Piano manufacturer William Steinway, who developed the nearby manufacturing village of Steinway on the old Benjamin Pike estate, was also very attracted to “the beautiful and healthful situation on the water.” Partnering with brewer George Ehret, Steinway acquired a large piece of land along the shore and opened a pleasure garden and beach for his employees and the general public called Bowery Bay Beach. The beach opened in June 1886.

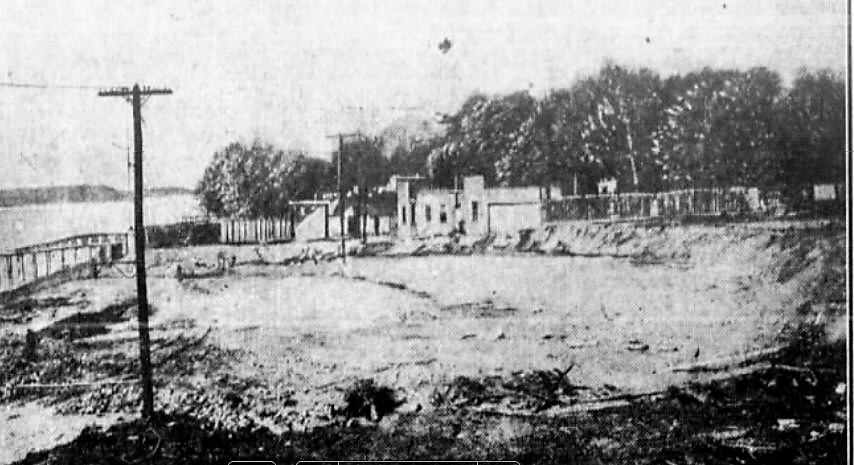

Steinway constructed a sea wall along the shore, followed by a 500-foot-long pier to accommodate large steamboats for up to 2,000 passengers (the pier was at the foot of present-day 87th Street). Hotels and two large bathing houses were erected shortly thereafter, and shady roads were laid out through the existing groves of trees. This photo was taken about 1923, several years after the facility had shut down.

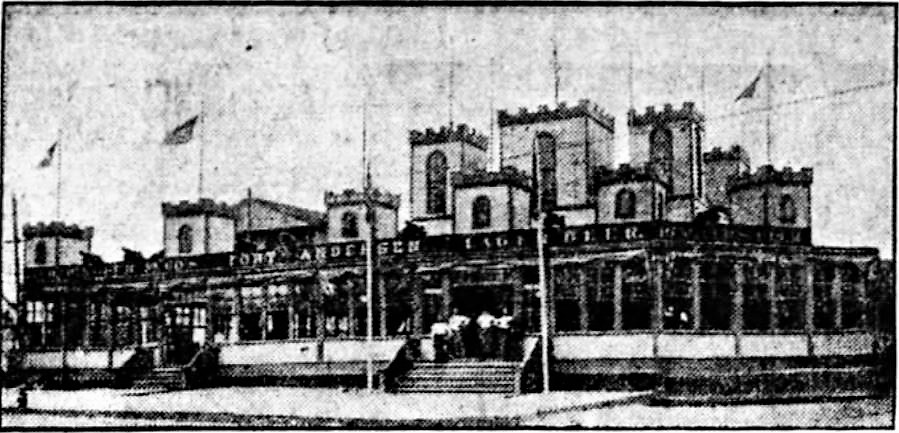

Bowery Bay Beach–later called North Beach–offered day and night swimming under the supervision of four lifesavers (there were more than 150 electric lamps installed on the site), in addition to great fishing, boating, dancing, pony rides, and picnicking. The pleasure park also had a well-appointed menagerie with rare and valuable animals, a fresh-water swimming pool, skating rink, shooting gallery, restaurants, beer gardens, nightly concerts, weekly fireworks displays, and much more.

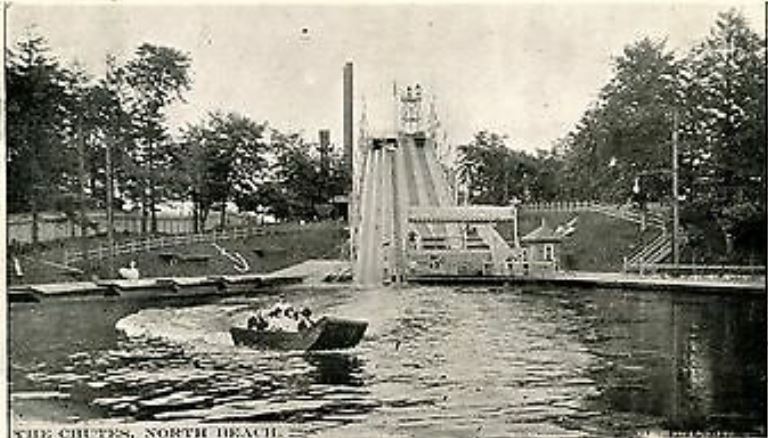

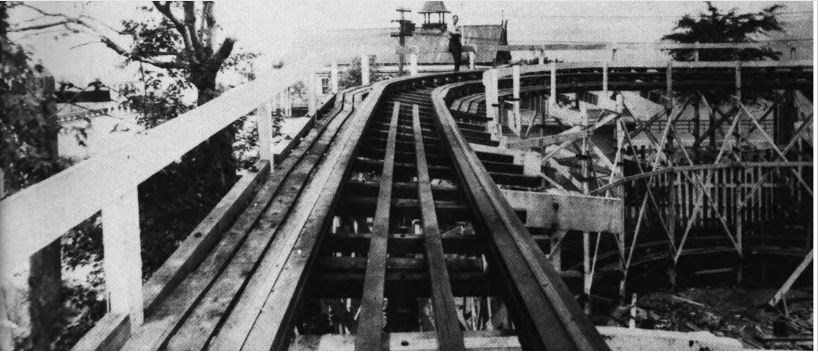

In later years, two amusement parks (Gala Park and Stella Park) were added to the North Beach pleasure park, with major attractions such as three carousels, two “scenic railway” roller coasters, a large circle swing, and a Shoot-the-Chutes flume ride featuring a pond with a boardwalk.

Much has been written about North Beach–and many photos of Bowery Bay and the park have been published (including a photo of teenage boys skinny dipping). What hasn’t received a lot of attention in all these years is what was buried forever when North Beach was turned into landfill to create LaGuardia Airport.

The Bodies Buried Under LaGuardia Airport

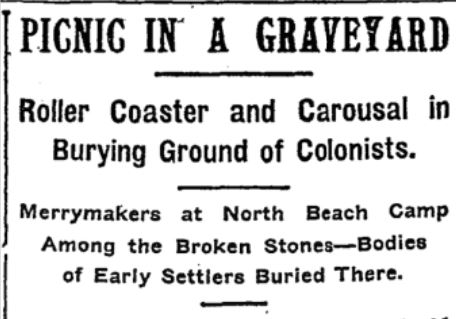

In 1903, a small article in The New York Times titled “Picnic in a Graveyard” reported on a small family graveyard “high up on the hills that surround old Bowery Bay.” According to the article, the grave site, “with headstone half standing” to mark the final resting place of the Rapelyes, Luysters, and other colonial families, was surrounded by a roller coaster, a carousel, and a dance hall. Here’s how the article described the scene:

“Picnickers camp along the stones and scatter their luncheon crumbs over the sod, while beyond, on the brow of the hill running up from where the North Beach car track turns, at the swimming tank, the brick foundations of the old Rapelye mansion serve as tables for yet other picnickers, who have chosen the vantage ground perhaps for the reason that Daniel Rapelye chose it—because it commands an unbroken view of the bay.” (Note: the Rapelye family owned numerous houses and barns along Bowery Bay, some of which were still standing up to 1939 or later.)

In 1907, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle also wrote about the old cemetery in an article titled “Graves Dug 200 Years Ago.” This article described the cemetery as “a small square of land on the top of a bluff overlooking Bowery Bay” with a “gnarled apple tree” standing at each corner.

The reporter had found 34 graves among four rows of tombstones made

of brownstone, granite, and schist (but broken ends and mounds indicated the presence of more). Of these, he was able to read 23 inscriptions dating from 1696 to 1827. Here is what he wrote about the burial grounds:

The earliest date was on the tombstone marking the grave of Mary Luyster, the wife of Daniel Rapelye. As the reporter noted, Mary died in the year George Washington was born.

“Time has not been kind to this little cemetery. There is much to show the effect of years and some evidence that proves the work of vandals… The thoughtful visitor to that burial place will find much for reflection. The inscription on each tombstone tells a story in itself. It is a brief story, simply a step from birth to death, so to speak, but to read the lines carefully and to dwell upon events in the lifetime of the person lying under each stone makes the story a long one.”

In September 1916, a large fire destroyed a large two-story pavilion known as Unter den Linden, Morris’ Scenic Railway coaster, and the casino and pavilion of Herman Spivak. Although all of these structures were near the old graveyard, the tombstones remained untouched.

North Beach Makes Way for an Airport

One year later, in February 1917, the North Beach Amusement Company (formerly the Bowery Bay Beach Improvement Company) announced it was suspending operations. Many things contributed to the pleasure park’s downfall, including an infantile paralysis epidemic in 1916 that forced the beach to close, World War I, several large fires, and Prohibition.

By 1926 the grounds had been reduced to their original weeded woodland state, with only remnants of the concession stands, a scenic railway coaster, and the carousel shed still standing. The main pier had burned down in 1926, a few hotels had reverted to family residences, another dance hall burned down in 1927, and the scenic railway blew down during a wind storm in 1928.

Even without so much as a fence around it, the cemetery remained intact.

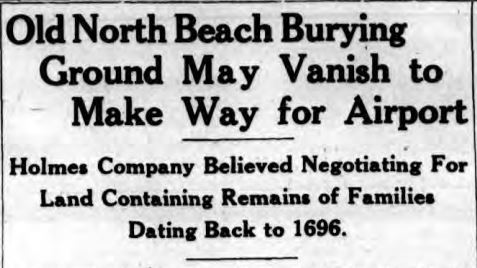

In February 1929, Holmes Airport Inc, which had a nearby airfield, started exploring options to add a seaplane base on Bowery Bay. The site they were considering was close to the old family graveyard. However, it was uncertain whether the graveyard would have to be removed to make way for the seaplane operations.

By this time, the North Beach pleasure grounds had been closed for about 12 years. The passage of time had caused the tombstones to sink even deeper in the soil, and many of the stones had been removed or covered with grass and weeds.

But even in 1929, Mary Luyster’s tombstone was still legible, as were the graves of two men named Daniel Rapelye, and also Cornelius Rapelye, Rensie Schenck, Susanna Brinckerhoff, Cornelius R. Purdy, Elbert Luyster, Ann Noorstrant, Cornelius Luyster, Sarah Luyster, and Jane Luyster (about five of the legible tombstones marked the graves of Luyster children who died at a very young age).

Holmes Airport never did get a seaplane base — Glenn H. Curtiss beat them to it. By May 1929, Curtiss Flying Service was offering two trips a day in its Sikorsky amphibians to Atlantic City. Work was also beginning to extend the facilities by nearly 100 acres to accommodate passenger land planes.

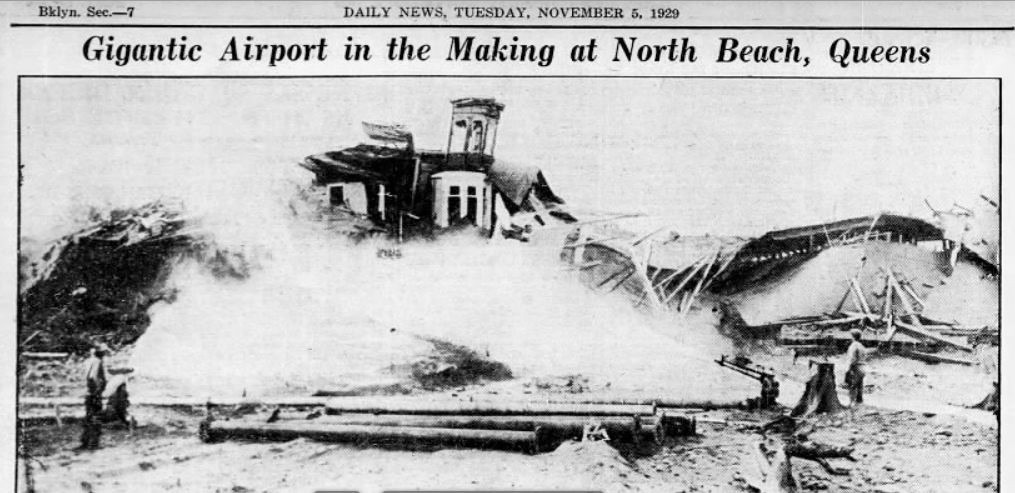

In the summer of 1929, “German-castles-on-the-Rhine” which once housed concessions were torn down, the “shaky stilts” from the burned roller coaster were removed, and the Shoot-the-Chutes on the hill was demolished. The old Fort Anderson dancing pavilion was torn down to make room for a hangar and all the contents of the Mammouth Photo Studio, including horses stuffed with excelsior, fake wave backgrounds, and other props were burned and destroyed.

All of the old park structures, as well as the surrounding hills and houses, were washed away by huge hydraulic pumps for use as landfill, reducing North Beach “to a flat plain of 150 acres.”

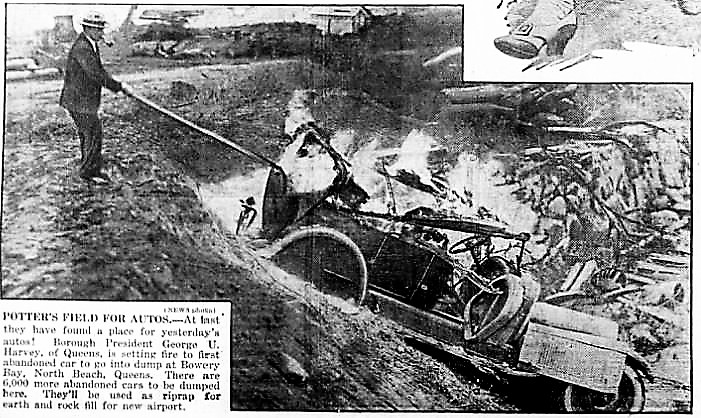

For added good measure, about 6,000 or more old cars that had been abandoned on highways and confiscated by the police were burned and dumped into Bowery Bay to form a foundation for the extension into the bay by 500 feet. “The old cars were found to be almost ideal material for this purpose,” one news article reported in June 1930.

Wreckage from the old Waldorf Astoria and Columbia Burlesque Theatre was also reportedly trucked across Astoria and dumped into the bay, along with 300 old safes and two old paddle-wheel boats.

And still, the old Rapelye/Luyster cemetery remained untouched for another six years.

In June 1938, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that the graves of the old family burial ground were to be removed from the site of what was then called the North Beach Airport. The paper reported that 46 graves had been discovered, but most of the markers were either missing or illegible by this time.

The Board of Estimate appropriated $1,532 for their removal in order to allow the municipal airport to expand its western boundary. The remains were interred in nearby St. Michael’s Cemetery so that work on the new airport could proceed.

Today, if you park your car in the Terminal A parking lot on the west edge of LaGuardia Airport, you might want to think about the 47 adults and children who were once buried under that very spot.

I remember reading about Strato Lizzie and her unsolved disappearance in one of the old papers. I hope someone took her in and gave her a safe, happy–if unpublicized–life.