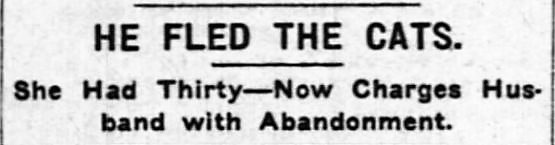

Anna Kaiser was a crazy cat women. Her husband, Hans, was not crazy about cats. Magistrate Ommen of the Yorkville Police Court had to take one side or the other, whether he liked cats or not.

Before the couple married, Anna (née Ammann) had about 50 cats. She agreed to get rid of 20 of them to please her would-be husband. I’m not sure how she did this; I’m pretty sure I don’t want to know.

I’m also not sure why he went along with the deal, but for some reason Hans agreed to marry Anna even though she still had 30 cats.

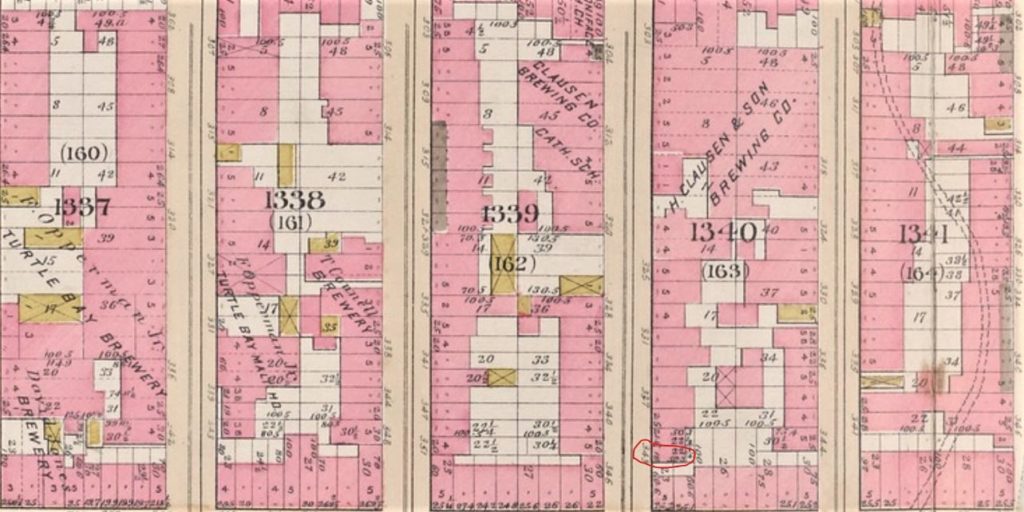

By 1903, Hans and Anna were living in their tenement apartment at 343 East 47th Street with about 20 or 30 cats, give or take a few. Hans supported his wife and her feline friends by working as a maltster, possibly at one of the many breweries in their Turtle Bay neighborhood.

Sometime in 1903, Hans kicked his 33-year-old wife and the cats out of their apartment. Anna moved in with her older sister, Pauline Van Mauderoth, who lived with her husband, Boddo, just two blocks west of the Bronx Zoo at 2361 Crotona Avenue. (We may guess where some of the cats ended up.)

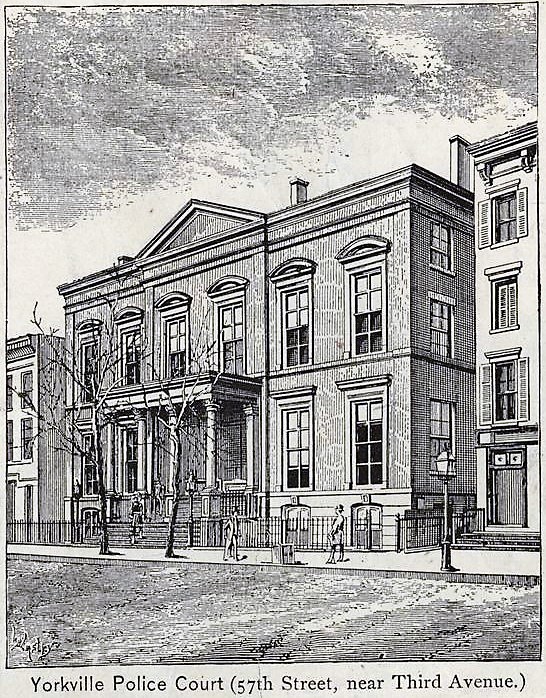

Two years after being kicked to the curb, so to speak, Anna filed charges against her husband for abandonment and nonsupport. The couple argued their cases before Magistrate Alfred E. Ommen in the Yorkville Police Court on March 14, 1905.

Kaiser vs Kaiser und Katzes

At the Yorkville Police Court, Hans admitted that he had deserted Anna because she kept “too many cats for his peace and comfort.” Hans told the magistrate: “It was a case of too much cats. She liked cats so much that she liked them better than me. She never cooked for me, but spent all her time looking after her cats, twenty-five or thirty of them. They made all kinds of horrible noises. She used to roam the streets at night picking up stray cats and bring them home to make it worse for me.”

Anna agreed that she liked cats. “Before I was married I had fifty cats, but my husband was so particular that I had to get rid of about twenty of them.”

I don’t know if Magistrate Ommen was a cat man or not, but he sided with Anna and ordered Hans to pay his wife $3 a week for her support. (He did not state what percentage of that amount could be used to support the cats.)

Things apparently did not work out for Anna and Hans: According to a 1915 census report, Anna was still living with her sister and brother-in-law in the Bronx 10 years after the court hearing. She reportedly worked as a bookkeeper (perhaps the $3 a week was not enough to support all her cats).

A Brief History of the Yorkville Police Court

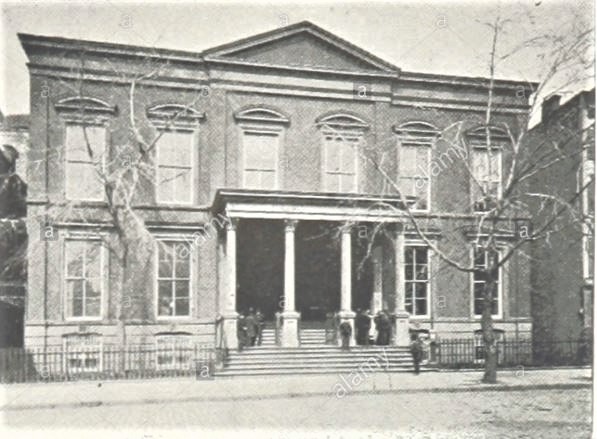

The Yorkville Police Court building was located on 57th Street between Lexington and Third Avenues. Also called the Fourth District Police Court (and later, the Seventh Judicial District), the court served the 18th, 19th, 21st, 22nd, and 28th Police Precincts.

New York City’s police court system was established in June 1845 under an ordinance titled “An Ordinance Regulating the Police of the City of New York.” The ordinance established four police districts, each comprising a police court and office that served multiple wards. The Fourth District comprised the Twelfth, Seventeenth, and Eighteenth wards.

Originally, the police court for the Fourth District was housed in the police station house on East 29th Street, in the Eighteenth Ward. Under an amendment to the law in December 1848, the Fourth District Police Office was abolished, and for many years the city had only three police courts.

An act was passed on April 17, 1860, to erect a new police court house on 57th Street, just west of Third Avenue. Construction began in 1862.

In the interim, court for the district was held in a building owned by New York City postmaster Abram Wakeman at the corner of Fourth Avenue and 86th Street. This temporary court was actually located in the Yorkville neighborhood, which is perhaps why the court was often called the Yorkville Police Court, even when it moved downtown to 57th Street.

Hugh Gaine: The Turncoat Printer of the Revolution and “The Greatest Liar on Earth”

What do too many cats and the Yorkville Police Court have to do with an Irish printer who changed sides during the Revolution more times than I change my cat’s litter pellets in the course of a month?

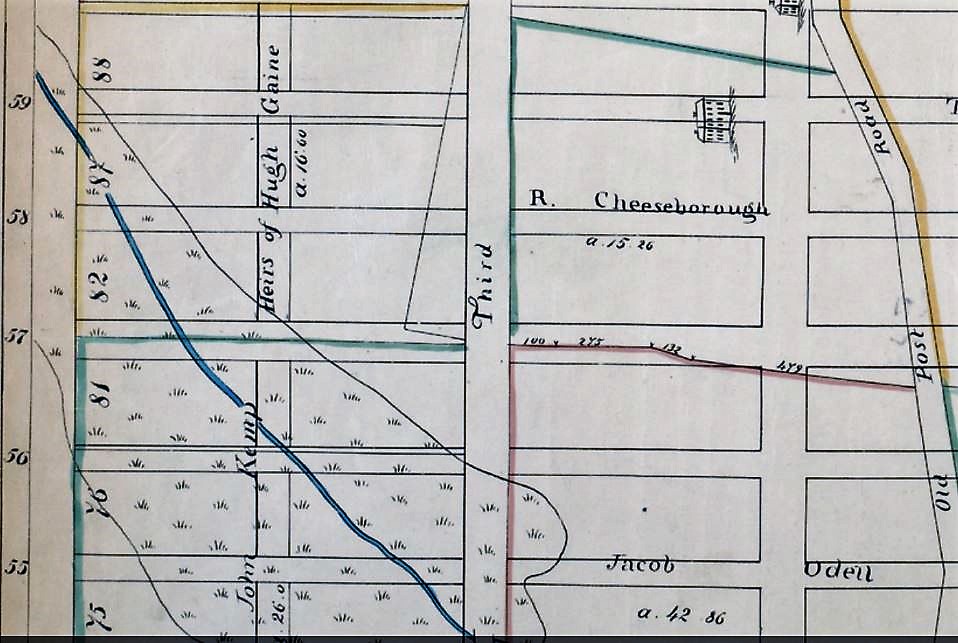

The connection is the land on which the Yorkville Police Court building was constructed. East 57th Street was once part of a large plot of land–about 56 acres–that Hugh Gaine owned prior to his death in 1807.

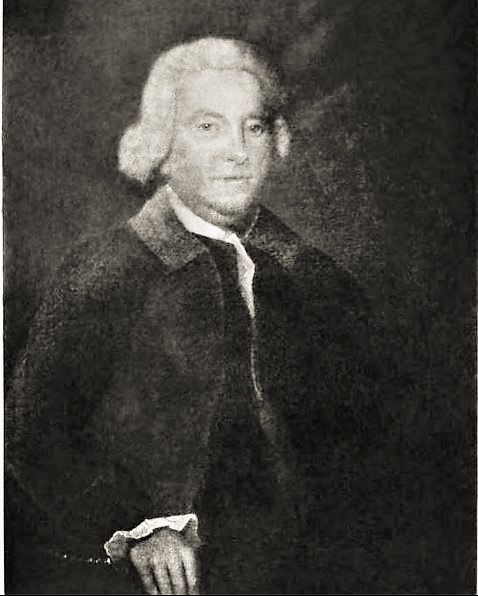

Born in Belfast, Ireland, in 1726, Hugh Gaine started his printing career at the age of 14 as an apprentice for the printers Samuel Wilson and James Magee. In 1745, he came to America and became a journeyman for James Parker, the printer-editor of the New York Weekly Post-Boy.

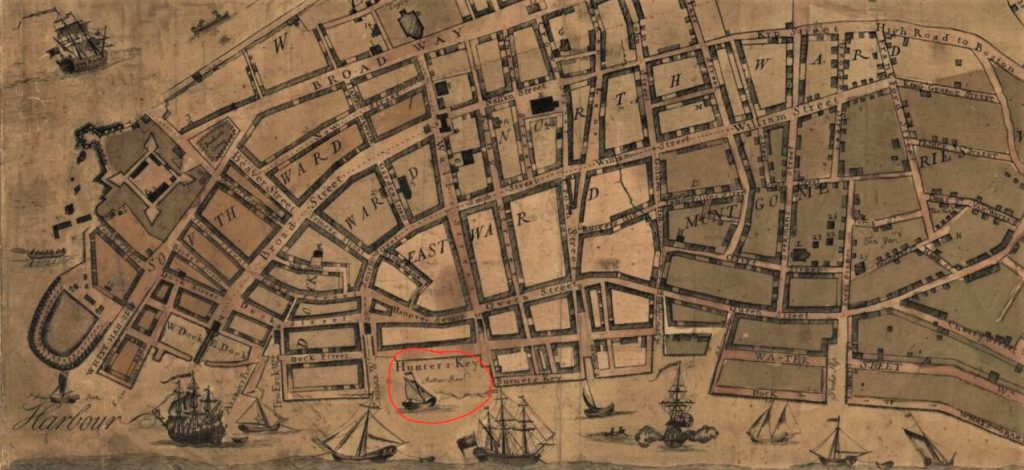

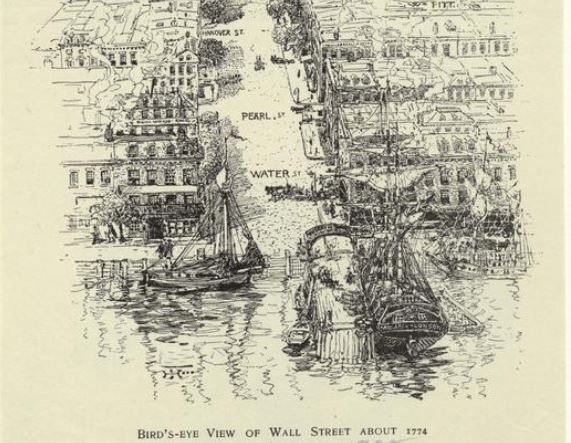

In 1752, Hugh started his own printing business (more of a book-selling business) with William Weyman at a shop on Hunters Key (or Quey) on the East River. Hugh and William sold Bibles, psalm books, theater tickets, and writing papers. It was at this location that Hugh started publishing his new newspaper, the New York Gazette and Mercury (the first issue was November 12, 1753.

In 1757, Hugh Gaine moved his printing shop–now called the Bible & Crown–to a large corner lot that he later purchased on Hanover Square, on the southwest corner of Wall Street and Water Street. This building, later numbered 116 Water Street, was three stories with two rooms on each floor.

According to an advertisement that Gaine later placed to lease the property, the house featured a main kitchen, cellar, cellar kitchen, cistern, pump in the yard, and the privilege of passage to the dock (which was then only one block away).

In 1759, the same year that he purchased the print shop on Hanover Square, Hugh married Sarah Robbins at Trinity Church. They had three children: John R., who died in 1787; Elizabeth, who married John Kemp, a professor at Columbia College; and Ann, who died in 1845.

Soon after Sarah died in 1769, Hugh married a widow, Mrs. Cornelia Wallace. Hugh and Cornelia had two daughters: Cornelia A., who married Anthony A. Rutgers, and Sarah, who married Harmon G. Rutgers.

During the Revolutionary era, Hugh initially took up the cause of the Patriots–in fact, on July 16, 1776, his newspaper was the first publication to publish the Declaration of Independence in New York City. That year, when the British took over New York, Gaine fled to Newark, New Jersey, where he continued printing his newspaper.

However, a few months later he flipped and joined the Tories, a move that greatly angered those Americans who were fighting against the British. Hugh Gaine continued to support the Royalist cause on and off until the newspaper folded in November 1783 under charges of treason (it was taken over by John Holt).

Many men thought that Hugh Gaine surrendered his political convictions too readily, especially when his financial security was at risk.

The Pennsylvania Journal once called him “the greatest liar on earth”; author and editor James Grant Wilson noted: “When with the Whigs, Hugh Gaine was a Whig; when with the Royalists, he was loyal; when the contest was doubtful, equally doubtful were the politics of Hugh Gaine.”

Hugh Gaine died April 27, 1807, at the age of 81. He was buried in the family vault in the Trinity Church graveyard.

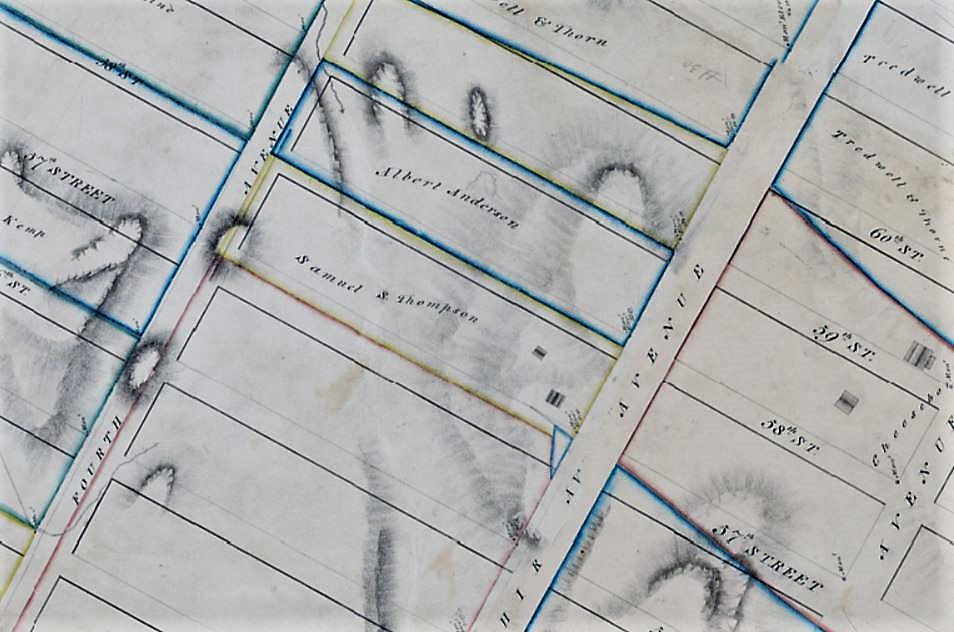

In 1816, his heirs sold off his property along Third Avenue to Samuel S. Thompson, Elbert Anderson, and several other men.