On a late summer day in 1909, during the dog days of August, to be exact, a reporter for the New York Sun noted that there were almost as many cats on Morton Street as there were politicians. I’m not sure if he meant “as there were politicians on Morton Street” or if he meant “as there were politicians throughout New York or the entire country,” but I still laughed when I read that comment.

To demonstrate his point, the reporter shared a tale about a young mother named Sadie Martin, who had a remarkable encounter with several felines while making her way home one day.

According to the story, Sadie had just purchased a porterhouse steak, which she placed in her baby’s carriage for safe keeping. Right in broad daylight, a cat sneaked up to Sadie, jumped into the carriage, and snatched the steak.

A passerby named Joe Margoli saw the brazen theft and went running after the cat. By the time he caught up with the cat burglar, three more cats had latched on to the piece of meat. Joe was able to pull the steak away, but as he ran back to Sadie the cats tried to climb up his trousers.

“Ain’t it awful!” Sadie told the reporter. “Joe was real brave, if he is a dago.” (The reporter explained that Italians were not very much appreciated in Greenwich Village.)

While many of the residents of Morton Street may not have been fond of the Italians, they were very protective of the cats. If anyone tried to harm one of the cats, the children would scream for their mothers, who would in turn “thrust their non-pompadoured heads from the windows and marshal the youthful corps to the rout of the assailant.”

As a result, the cats of Morton Street became quite complacent, secure in knowing that they could nap in peace on the cobblestones, because the children would yell out to any horse team driver to watch out for them. Should a mother cat fall victim to a horse cart, the human mothers and their children would come to the kittens’ rescue armed with bottles of milk and pieces of meat.

The Anglican Cats of Trinity Church

On Fridays, when the fish peddlers made their way down Morton Street, cats would come out of every cellar, stable, and tenement building and surround the peddlers. Sometimes the fishmongers would fling a few fish morsels, sending the cats into a feeding frenzy.

Perhaps the Morton Street cats were so serious about getting their fish on Fridays because they were Anglican cats of the Trinity Church, whose members practiced abstinence (no “flesh meat”) every Friday of the year back then. More likely they were just starving, but I prefer the first explanation.

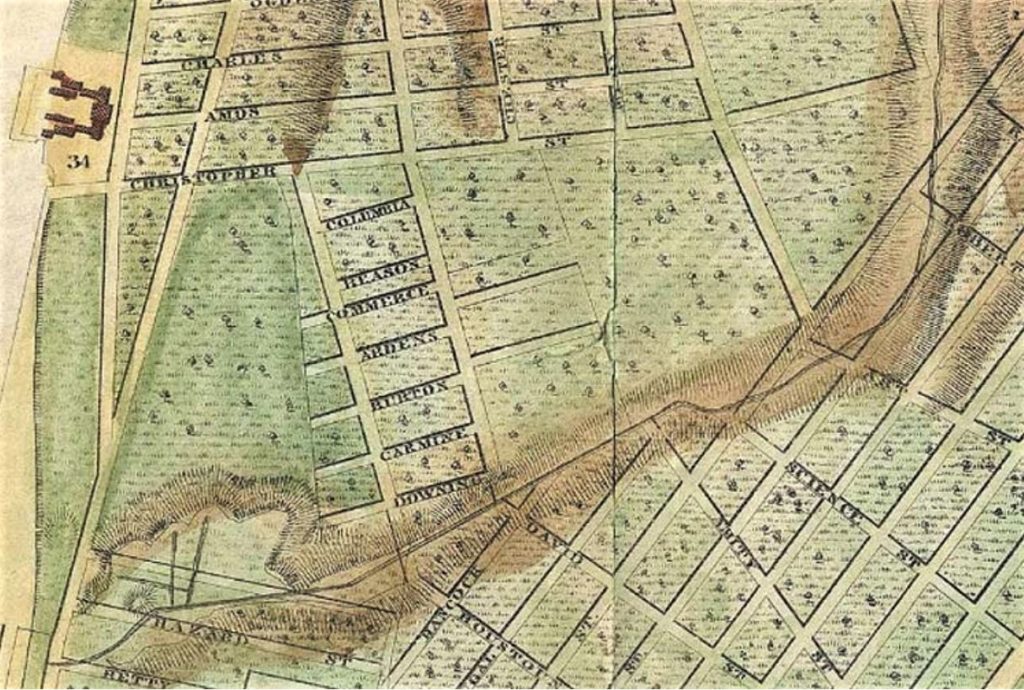

You see, going back to the late 1600s, much of the land along the Hudson River from Fulton Street to Christopher Street (about 215 acres total) was owned by the Trinity Church Corporation. Since the cats of Morton Street were orphan felines, they were technically the property of the Trinity Church. (Yes, I’m stretching things here, but it makes for a good story with interesting history.)

The Reverend’s Farm

The history of Trinity’s vast acreage dates back to 1630, which is when Roeloff and Anneke (or Annetje) Jans first arrived in the colony of New Netherland. The couple and their children settled in Beverwyck, now Albany, where Roeloff worked as a manager for Adrian Van Rensselaer, the first patroon of the Van Rensselear Manor.

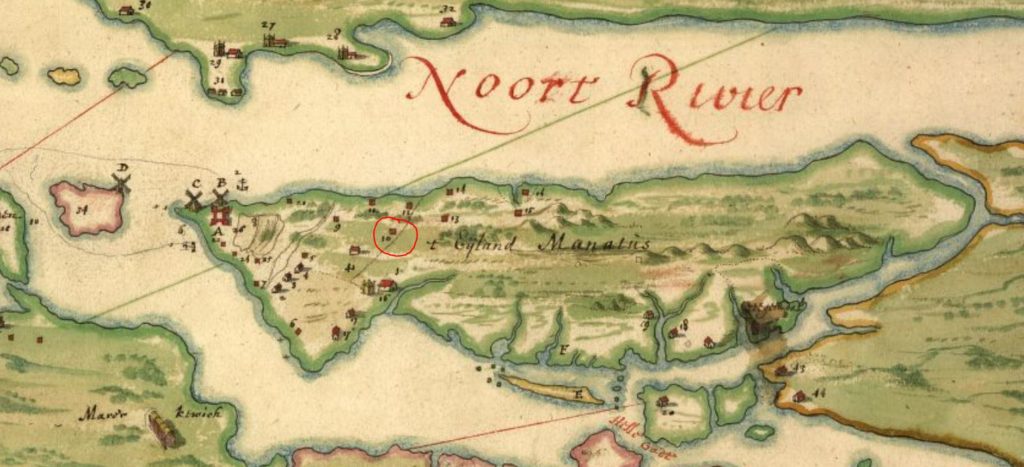

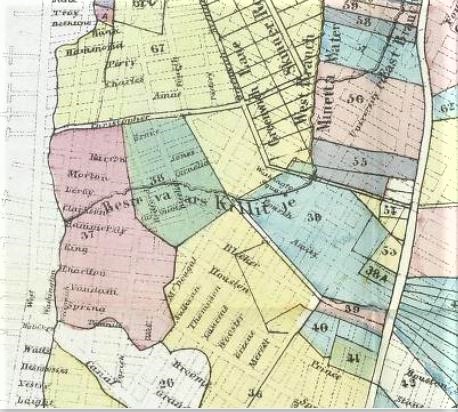

In 1636, two years after the Jans family returned to Manhattan, Wouter Van Twiller, the second director general of New Amsterdam, granted a 62-acre parcel of his land north of the wall (today’s Wall Street) to Annetje and Roeloff. (Van Twiller had been using much of his land holdings for his personal plantation, called Bossen Bouwerie, where he cultivated tobacco.)

There is no exact record of the boundaries, but according to a book titled Anneke Jans Bogardus: Her Farm, and How it Became the Property of the Trinity Church (Stephen P. Nash, 1896), the land was bounded by about present-day Chambers Street and Watts Street along the North River (Hudson River).

A year after her husband died in 1637, Annetje married the Reverend Everardus Bogardus, the pastor of the Dutch Reformed Church. The farm came to be known as the Dominie’s Bowery, or Reverend’s Farm.

The family did not live on the farm; they occupied a house that had been built for the reverend near his church at the fort (the Battery).

Following her husband’s death in a shipwreck in 1647, Annetje returned to the Albany region, where she died in 1663. In accordance with her will, dated January 29, 1663, her first-born surviving children (i.e, those fathered by Roeloff) were to sell the farm and split the proceeds.

The Jans heirs sold the land to Francis Lovelace, the new English governor of the colony, in 1671. The land was later merged with another large tract, creating a 215-acre parcel called the King’s Farm.

The northern boundary of this farm was in today’s Greenwich Village, near Christopher Street.

In 1697, colonial Governor Benjamin Fletcher leased the King’s Farm to the brand-new Trinity Church–which he had established at the corner of Wall Street and Broadway–for a term of seven years. Eight years later, Queen Anne granted the entire 215-acre parcel (now called the Queen’s Farm) to Trinity Church.

The grant made the church the second-largest landholder in New York and eventually the wealthiest in the North American colonies.

Trinity Church Charged by the Health Board

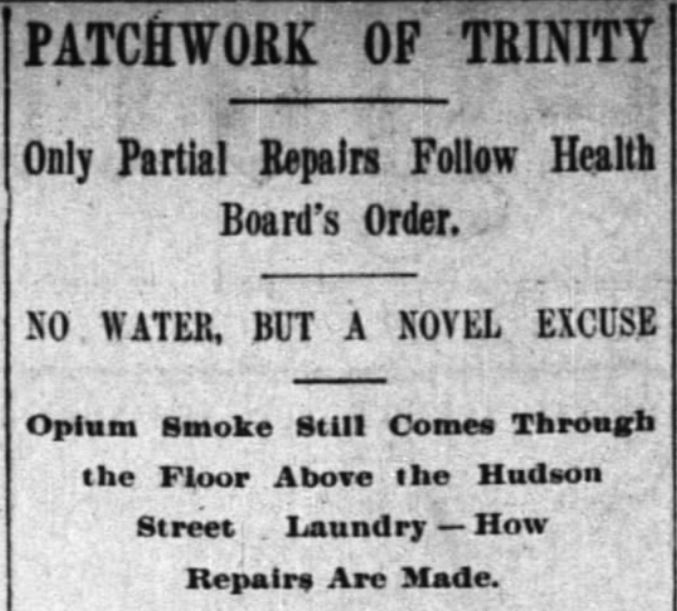

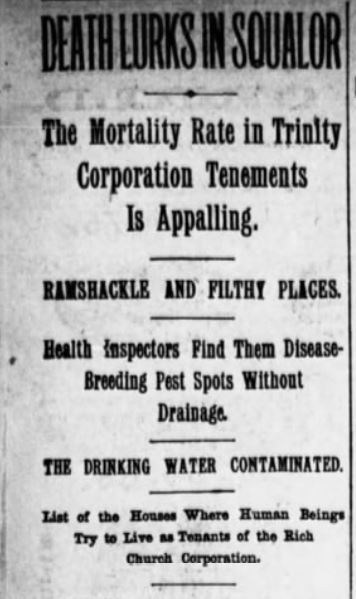

As the years went by and the city’s population continued to boom, many of the buildings on the nearly 1,000 lots owned by Trinity Church became rundown and dilapidated.

Talk about an absentee slumlord: the church took a completely hands-off approach when it came to maintaining the buildings on its property. The church believed its only responsibility was to collect the ground rent, so they placed the onus on the building managers for all upkeep and maintenance.

In 1894, a state-chartered Tenement House Committee released a 600-page report on New York’s substandard housing in which they called out Trinity Church for ignoring disease, vermin, lack of ventilation and running water, aging infrastructure, and other problems. Following the hearings, the New York Times researched and published a list of every building it could find that was built on the old King’s Farm (the church refused to provide a list of its properties to the public).

Even after being sued by the city’s Department of Health for failure to provide access to water in its tenements as required by law (1887), the church tried to fight the law and only reluctantly agreed to update some of its oldest buildings.

By the early 1900s, the church found that it was easier to just sell off most of its holdings.

In 1910, a year after this Morton Street cat tale takes place, the Trinity Church Corporation sold an entire block front bounded by Greenwich, Washington, Morton, and Barrow Streets to James H. Cruikshank.

The exact price was not made public, but it was estimated to be about $450,000.

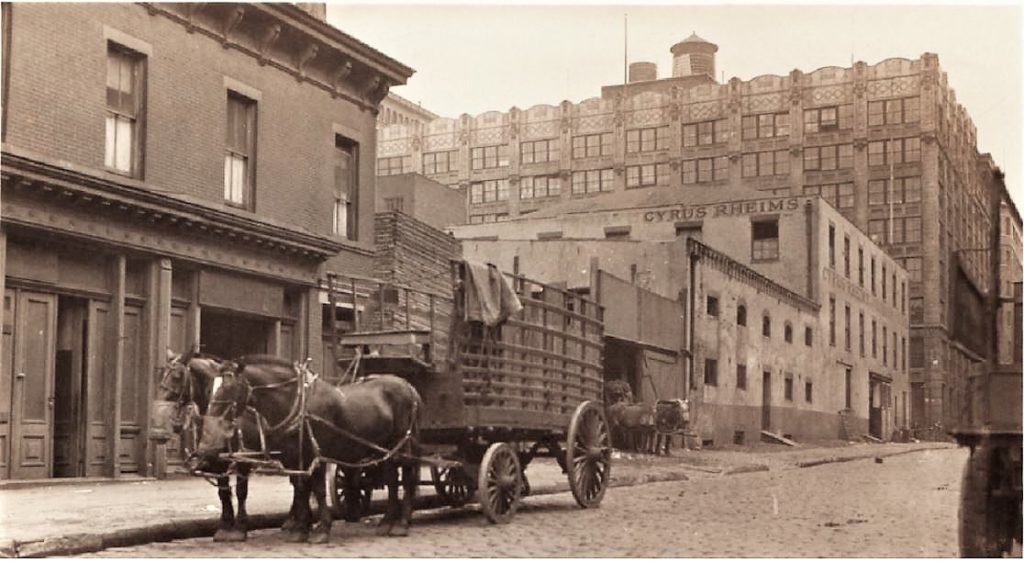

The buyer intended to raze all the old frame and brick buildings (about 25 buildings in total on 16 lots) and replace them with 8-story fireproof mercantile loft buildings.

Over the past 100 years, the 215-acre King’s Farm has been reduced through donations and sales to a mere 14 acres, including 5.5 million square feet of commercial real estate. The vast majority of the Trinity Church property is in Hudson Square, a commercial neighborhood next to the Manhattan entrance to the Holland Tunnel.

Today one of the 1910 loft buildings that replaced the old Trinity Church buildings pictured below is the New York City headquarters for PayPal and Venmo. With its rooftop garden, free gym, music room, and free catered meals, it looks like a fun place to work.

I wonder if the company would like a few office cats…