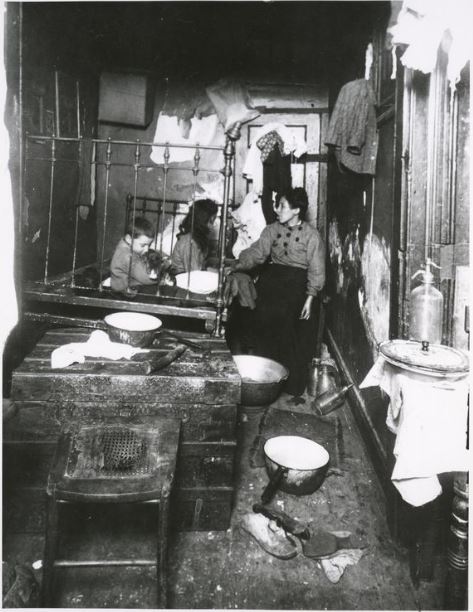

A tenement house in New York is any building or part thereof which is occupied as the residence of three families or more living independently of each other and doing their own cooking in the premises. It includes apartment houses, flat houses and all other houses of similar character.”

–John J. Murphy, Commissioner of the Tenement House Department, Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science in the City of New York, April 1915

The Grid and the Tenement House

Manhattan’s rectangular grid plan of streets, established by the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811, allowed for standard building lots measuring 25 feet by 100 feet. These long and narrow lots were OK for the old frame houses and smaller row houses that had been constructed in the 1700s or early 1800s. But the “old-law” tenements constructed in the mid-1800s tended to occupy about 90 percent of the lots, which did allow much room for natural light or air shafts.

Those buildings that did not occupy the entire lot often featured “rear tenements” in the back yards, which provided even fewer windows and worse conditions for the residents than did the buildings facing the streets. The dense, crowded, and unregulated conditions created a perfect breeding ground for disease and disaster.

In 1900, New York City finally recognized that the problems associated with multiple dwellings–including fire code violations and a substantial outbreak of diseases such as cholera and tuberculosis–had reached such epic proportions as to require its full and immediate attention.

Although a set of regulations titled the Tenement House Act had been placed on the statute books in 1867 (when there were only about 500,000 people living in tenement houses), enforcement was divided among the city’s health, buildings, fire, and police departments. This division created duplication of effort at best and non-enforcement at worst.

So in 1900, New York State Legislature created the New York State Tenement House Commission, which in turn established the city’s Tenement House Department (THD). According to THD Commissioner John J. Murphy, it was the department’s responsibility to “attempt to prevent evil conditions by operating in three directions–structural, sanitary and sociological.”

The THD had jurisdiction in three areas:

• New building construction plans to ensure conformity to laws regarding light, ventilation, fireproofing, fire egress, and sanitation

• Alteration of old buildings such as railroad flats and dumb-bell tenements to ensure conformity with newer fireproofing and sanitary standards (at one point, the only sanitary accommodation for over 10,000 tenement houses were school sinks in yards)

• Ongoing inspection of tenement houses to ensure fire escapes were kept cleared (many residents treated fire escapes as balconies suitable for furniture and playing children); rubbish was removed from cellars (rubbish included dead cats, dead rats, filthy rags, fecal matter, and food garbage); and sanitary standards were met

By 1915, when New York City had 104,000 legal tenement houses occupied by about 4.25 million people, the THD was able to report on its success. Commissioner Murphy noted that, due to the large number of buildings that had been altered to meet the requirements of the tenement laws, the department had been functioning “with a constantly lessening budget” as there were fewer complaints and issues. In fact, he said he was able to reduce the department’s working force by 63 men in the past year.

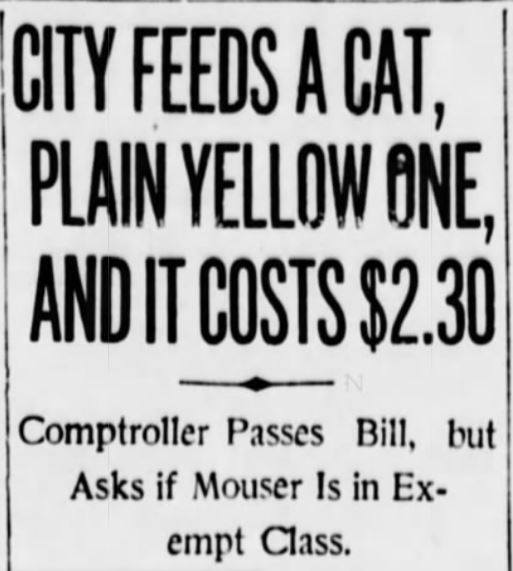

I’m not sure if that number included the cat, which appears to have arrived on the scene of the THD offices in 1911.

The Official Cat of the Tenement House Department

The THD office cat was just “a plain yellow cat” that had somehow managed to get on the city payroll even though he did not take the required civil service exam. For the cat’s services as office mouser, he was rewarded with five cents’ worth of meat and five cents’ worth of milk every day.

When the cat’s total expenses had reached $2.30, Commissioner Murphy submitted a bill to City Comptroller William Ambrose Prendergast. The bill, which covered a period from April 5 to April 31, was delivered to the comptroller by James McKeon, a messenger.

Upon receiving the curious bill, the comptroller sent the following letter to Commissioner Murphy:

Frankly, my dear Commissioner, I am puzzled about this claim. The city, under its charitable system, furnishes food and drink to the poor and needy: under its corrective system it supplies sustenance to those detained for criminal offenses. Outside of these classes the city pays only the equivalent for good received or services rendered. Where does the cat come in?

Under the civil service law payments for services must receive the approval of the Municipal Civil Service Commission. No certificate of that commission is attached. No salary has been fixed by the Board of Aldermen.

May I suggest a conference with the Civil Service Commission, to which representatives of the Reform Association might be invited, to consider whether the cat is to be placed in the exempt or competitive class.

I have thought of having the expense of the department cat paid out of corporate stock, but have not yet been able to reach the opinion that the cat constitutes a permanent improvement from which posterity would receive a benefit. I am sending the bill along in its regular course, but at your convenience will you please give me your views about the cat?

It seems to me that Comptroller Prendergast had way too much time on his hands, but his silly letter did receive national press coverage.

As one newspaper explained the situation, although the cat rendered services, there had been no competition for the position of mouser provided by the Civil Service regulations, nor was the feline classified as exempt.

And although the cat–having nine lives and a reputation for “coming back”–would probably be as permanent as the office furniture and other equipment, one could not classify a cat as a “permanent improvement.” (I beg to differ…)

The Tenement House Department had three offices: 44 East 23rd Street in Manhattan, pictured here in 1928; 2806-2808 Third Avenue in the Bronx, and 44 Court Street in Brooklyn. I assume the office cat was employed at the Manhattan building, where Commissioner Murphy had his office.

Between 1902 and 1920, the New York City death rate fell from 19.90 per thousand to 10.96; although other factors had their influence as well, substantial credit must go to the Tenement House Act. The act did not live up to the extravagant hopes of its advocates—it did not eradicate the slum nor provide decent homes to all who needed them—yet it did accomplish about all that could realistically be expected of a single piece of regulatory legislation.”—Tenements and Takings, Fordham Urban Law Journal, Vol. XVIII

The Tenement House Department was abolished in 1937 and merged with the Department of Buildings to become the Department of Housing and Buildings in 1938. This agency is now called the New York City Housing Authority, or NYCHA for short.

Today, NYCHA is the largest public housing authority in North America, employing over 13,000 employees to serve about 176,000 families and approximately 403,000 authorized residents. I’m not aware of any felines on the current NYCHA payroll.