Part II of a 2-Part Cat Tale

In the first part of this cat tale of Old New York, we met Lillian Russell, the mascot cat for the old nine-hole Dyker Meadow Golf Club in Brooklyn. Lillian was a talented fisher-cat who spent most of her eight years of life on the golf course or in the clubhouse.

In Part II, I will tell you what happened to Lillian Russell and explore some more of the Dyker Meadow Golf Club history.

Requiem for Lillian Russell the Fishing Cat

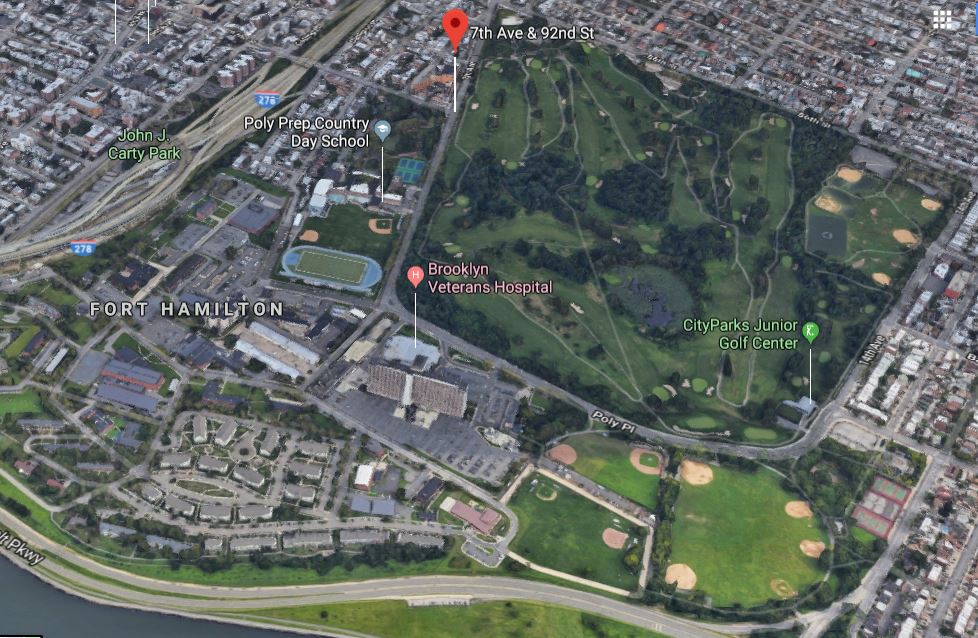

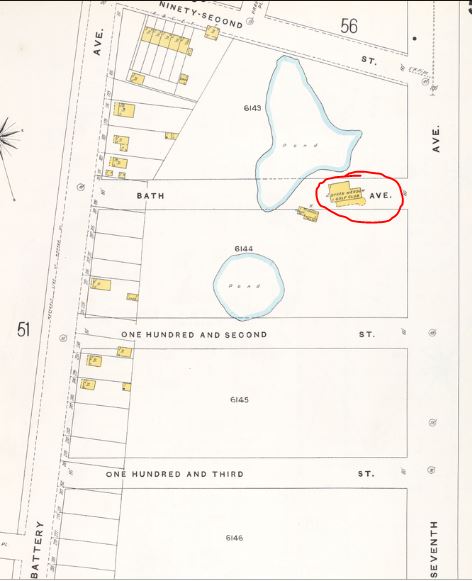

Lillian Russell was a large tabby cat who served as the feline mascot for the Dyker Meadow Golf Club, then located along 7th Avenue between 92nd Street and Cropsey Avenue in the Fort Hamilton section of Brooklyn (now the site of the Poly Prep Country Day School).

Named for the famous American actress and singer, Lillian Russell had arrived at the course in 1900, five years after the links were established.

The Dyker Meadow golfers were as proud of Lillian as the members of the neighboring Marine and Field Club were of Bob, their canine caddie (more on Bob to come in a later post).

At every annual dinner, the members gave toasts to honor their cat and sang songs about their favorite feline. Her image was even featured on a trophy that the neighboring golf clubs would all compete for at annual tournaments.

Lillian Russell received a lot of great press during her tenure as the Dyker Meadow cat, especially whenever she gave birth to kittens. She reportedly had 88 kittens during her 8 years of life, most of whom found good homes with members of the golf course.

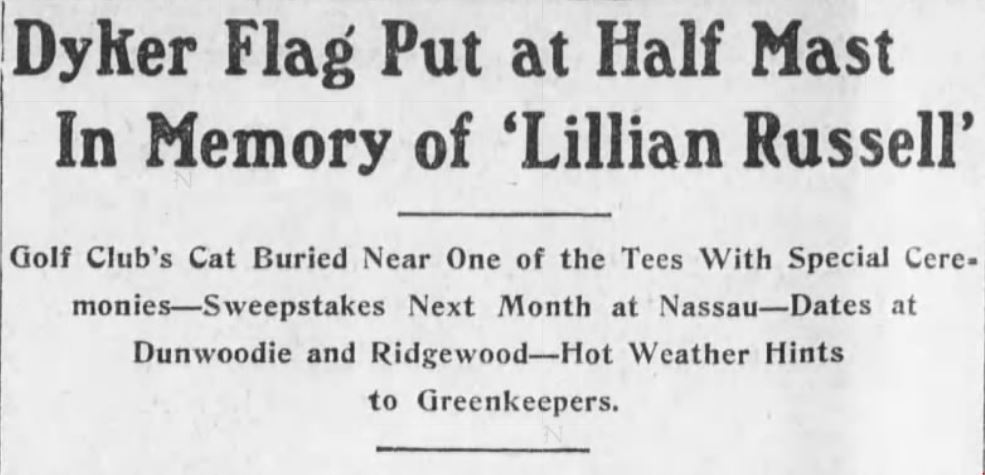

On July 30, 1908, a large story about Lillian Russell in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle provided an explanation as to why the flag on the Dyker Meadow clubhouse had been at half-mast for several days. Many residents thought the organization had its bunting only halfway up as a mark of respect for the late President Grover Cleveland, who had died on June 24 of that year.

According to the article, Lillian Russell had been found cold and stiff near her favorite fishing pond one morning, about an hour after she had followed one of the employees from the clubhouse. It was thought that she had gone down to the pond to get some fish and had died of old age (and probably too many litters of kittens). The members closely examined her body and could not find any wounds from firearms, dog bites, or rough caddies.

Lillian Russell had five kittens at the time, but because they were too young to be cared for (and foster cat parents did not exist back then), they all died. A box was fitted up, almost like a casket, for the interment, at which many members were present.

Lillian Russell was buried near one of the trees by the caddie house. The grave was not marked by a stone at the time of the burial, but it was thought one would likely be placed in the future.

Two years after Lillian Russell’s death, two of her prodigies–Lillian Russell II and Mr. Dkyer–were named “honorary and honorable” members of the club. By this time, the nine-hole course was an improved 18-hole course, through an arrangement with the adjacent Marine and Field Club.

A Brief History of the Dyker Meadow Golf Club

“The old Dyker Meadows down near Fort Hamilton have had a rise in the world. For years they have been associated with the humble cow and the meek sheep, and have furnished pasturage for generation upon generation of these animals. At last the day of recognition has come, and hereafter the meadows will be the haunt of the very nicest young men and women, for the golf experts of Brooklyn have decided that they supply a long felt want, and henceforth the Dyker Meadows will afford a new golfing ground for the new Brooklyn club that has adopted the name of the meadows for its own.”—New York Press, December 8, 1895

In 1894, the Dyker Meadows property was owned by Archibald Young of Bath Beach fame, who leased his lands to those who needed a pasture for their horses, cows, and sheep. By this time, though, big changes were already in the making for the historic property that had been home to some of the earliest Dutch settlers, and which had played a role in the American Revolution.

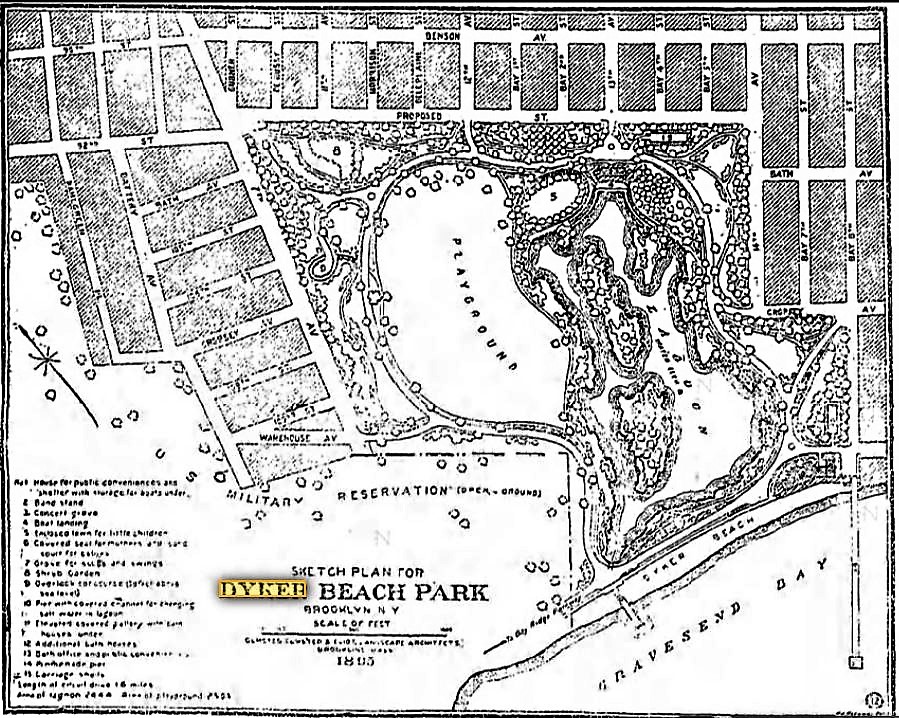

It was sometime around 1890 when the Dyker Meadows Land Improvement Company was formed to purchase all the property east of the U.S. government’s Fort Hamilton reservation. This syndicate of Brooklyn politicians then sold about a third of the land to the government for nearly as much as they paid for the entire tract. A few years later, the syndicate sold 144 acres of the tract to the city for $229,000, which the city planned to use for park purposes.

The new public park was to be “one of the pleasantest in the whole chain of beautiful grounds that Brooklyn has acquired for itself,” commanding the finest view, purest and coolest air, and converting “a lonely and unsightly marsh” into a delightful resort. Plans called for a system of paths, a flower garden, band stand and concert grove, enclosed lawn for children, a grove for swings, and other attractions. It would have been the second largest park in the borough after Prospect Park.

Plans for a large public park were eventually tabled in 1895, but about 44 of the city’s 144 acres were leased to a group of men who formed the Dyker Meadow Golf Club.

The Links at Dyker Meadows

Dyker Meadow Golf Club was established in 1895 with a membership of 100 under a governing committee composed of Timothy L. Woodruff, president; Edward H. Litchfield, vice president; Norman S. Dike, secretary; Frederick H. Webster, treasurer; and Daniel Chauncey, captain. The initiation fee for human members was $25, dues were $20. Cats did not have to pay dues.

Timothy Woodruff, a graduate of Yale (class of 1875), served as the first president of the Dyker Meadow Golf Club.

The 1.5-mile course was one of the few in the country properly entitled to be called “links,” referring to sandy, grass-covered soil on the sea shore. The links were laid out under the direction of George Strath, a Scottish professional golfer who had planned W.K. Vanderbilt’s course at Oakdale, Long Island, and Captain Beresford Webb.

The course featured many natural hazards, including three ponds that had to be crossed (and which promised to be “rich in golf balls” after a year of play). It was theorized that golfers would need at least five clubs, as opposed to the usual three or four required at other clubs.

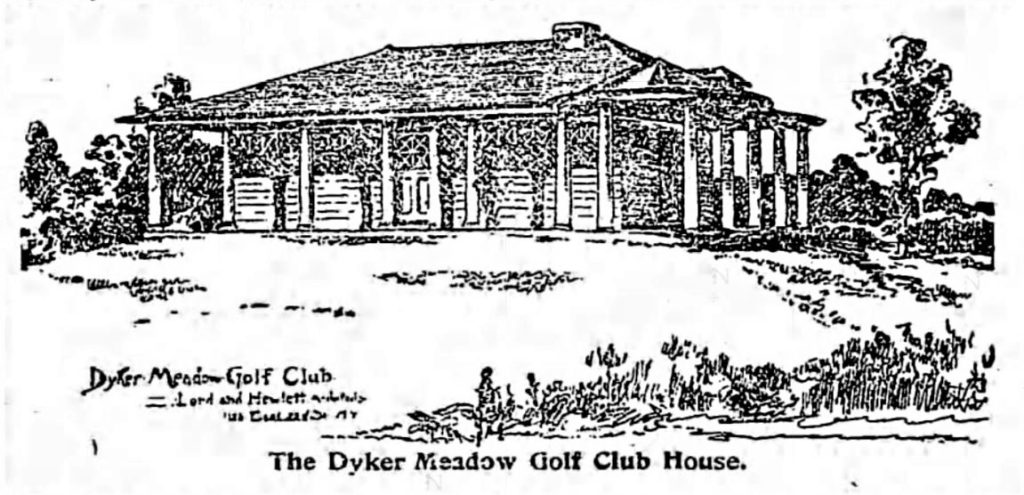

The Dyker Meadow Club House

“From the club-house and ninth green, looking to the south, nearly all the greens can be seen in one view, backed by the dancing waters of Gravesend Bay, where the white wings of the Atlantic Yacht Club flit by and the lighthouse on Sea Gate lifts its portentous finger like an exclamation point.”—Outing. An Illustrated Monthly Magazine of Sport, Travel and Recreation, April to September 1899.

Temporary accommodation for the golfers was provided until a new clubhouse was constructed on a hill at 7th and Bath Avenues in 1896. Designed by the architect and club member J. Munroe Hewlett, the 1.5-story clubhouse featured a broad veranda (which was reportedly a popular rendezvous for the ladies) and sweeping views of the links. The clubhouse opened on June 6, 1896.

The Final Days for Dyker Meadow Golf Club

Through the early 1900s, the Dyker Meadow golfers maintained exclusive access to their leased land as long as they “kept the grass mowed and the links in order.” This sweet deal came to an end in 1916, when the Poly Country Day School purchased the land for the site of its new school.

All of the Dyker Meadow members made arrangements to join other clubs in Queens and Staten Island. I don’t know if any cats were remaining at this time, and if so, which courses they chose to join.

Over the next few years, the Brooklyn Parks Department acquired additional parcels in order to carry out plans to create and expand what is now called the Dyker Beach Park and Golf Course.

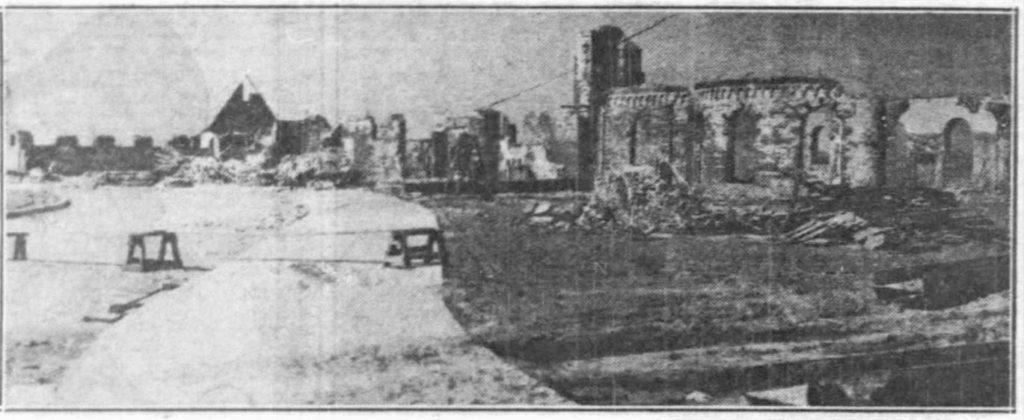

In 1932, plans were made to construct a new clubhouse on landfill facing Gravesend Bay at the foot of the new Dyker Beach Park. This building, “a palatial white elephant constructed without proper foundations by an incompetent commissioner and a grafting chief engineer,” was about 60 percent complete when, under the LaGuardia Administration, it was deemed to be badly designed and improperly located.

The building was condemned as defective to life and limb; reportedly, the piles were improperly set and many of them were not under the club foundation.